In 1991 Naomi Wolf wrote The Beauty Myth where she claimed women are oppressed by cultural pressure to be beautiful. What she failed to tell us is where this habit originated, and how it is essentially used to gain power over the male sex.

In human beings, various compulsions and desires come into conflict with one another, each jostling for momentary supremacy where one imperative will usurp the claims of another. That game has reached a problematical impasse during the last 800 years because, during that relatively short time span, human culture has thrown its patronage into developing, intensifying and enforcing sexual gamesmanship to the degree that our sexual compulsions appear pumped up on steroids and taken to extremes never before seen in human society (myths about widespread Roman orgies notwithstanding). The obsession with female beauty forms a significant part of the problem.

If we lived back in Ancient Greece, Rome or anywhere else we would view sexual intercourse as little more than a bodily function akin to eating, defecating and sleeping – a basic bodily function without the hype. After the Middle Ages, however, it developed into a commodity to pimp and trade, and the new cult of sexualized romance that arose from it resulted in a frustration of our more basic attachment needs – a frustration aided and abetted by social institutions placing sexual manipulation at the center of human interactions. This development entrenched a new belief that beauty was the native possession of women, and only women, and conversely that the desire to possess beauty was the lot of males alone, thus creating a division between the sexes that remains in place today.

Compare this division with the beliefs of older cultures – India, Rome, Greece etc – and we see a stark contrast, with classical cultures equally apportioning beauty to males and sexual desire to females. In ancient Greece for example males used to grow their hair long and comb it adoringly, rub olive oil on their skin and pay devoted attention to attire -the colors of the toga, the materials it was woven from, the way it was draped on the body- and there is perhaps no modern culture on earth where male beauty is more marvelously celebrated in the arts than it was in Greece.

Another example comes from the Biblical Song of Solomon, in which the appreciation of beauty and associated longing flows both ways between the man and women, whereas in romantic love beauty is ascribed only to the female, and desire only to the male – the roles are radically split. Moreover, in the Song of Songs there is no hint of the gynocentric arrangement; no appearance of man as a vassal towards women who are both Lord and deity. For the lovers in Song of Songs there already exists a God and so there is no worshipping of the woman as a quasi divinity who can redeem the man’s pathetic existence – as in “romantic” love.

According to Robert Solomon, romantic love required a dramatic change in the self-conception of women. He recounts;

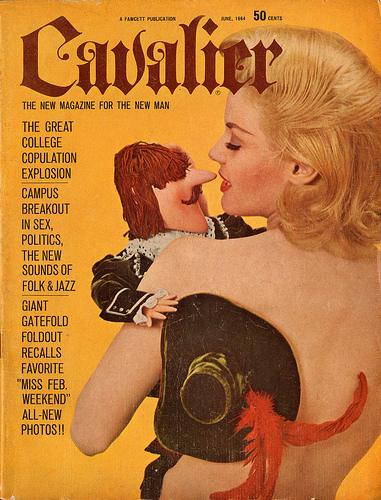

They too were freed from an identity that depended wholly on their social roles, that is, their blood and legal ties with men, as daughters, wives and mothers. It is in this period in Christian history that looks become of primary importance, that being beautiful now counts for possibly everything, not just an attractive feature in a daughter or wife (which probably counted very little anyway) but as itself a mark of character, style, personality. Good grooming, as opposed to propriety, came to define the individual woman, and her worth, no longer dependent on the social roles and positions of her father, husband or children, now turned on her looks. The premium was placed on youth and beauty, and though some women even then may have condemned this emphasis as unjust, it at least formed the first breach with a society that, hitherto, had left little room for personal initiative or individual advancement. The prototype of the Playboy playmate, we might say, was already established eight hundred years ago, and did not require, as some people have argued recently, Hugh Hefner’s slick centerfolds to make youth, beauty and a certain practiced vacuity into a highly esteemed personal virtue. The problem is why we still find it difficult to move beyond this without, like some Platonists, distaining beauty altogether – the opposite error. [1]

Modesta Pozzo penned a book in the 1500’s entitled The Worth of Women: their Nobility and Superiority to Men. The work purportedly records a conversation among seven Venetian noblewomen that explores nearly every aspect of women’s experience. One of the topics explored is women’s use of cosmetics and clothing to enhance beauty, including mention of hair tinting for which there is twenty-six different recipes. The following is the voice of Cornelia who explains that men’s sexual desire of women (and women’s control of that process via beauty) is the only reason men can love:

“Thinking about it straight, what more worthy and what lovelier subject can one find than the beauty, grace and virtues of women?… I’d say that a perfectly composed outer corporeal form is something most worthy of our esteem, for it is this visible outer form that is the first to present itself to our eye and our understanding: we see it and instantly love and desire it, prompted by an instinct embedded in us by nature. “It’s not because men love us that they go in for all these displays of love and undying devotion, rather, it’s because they desire us. So that in this case love is the offspring, desire the parent, or, in other words, love is the effect and desire the cause. And since taking away the cause means taking away the effect, that means that men love us for just as long as they desire us and once desire, which is the cause of their vain love, has died in them (either because they have got what they wanted or because they have realized that they are not going to be able to get it), the love that is the effect of that cause dies at exactly the same time.” [written 1592]

What I find interesting is that since the Middle Ages, as evidenced in Cornelia’s words, we have collectively conflated male love with sexual desire as if they are inseparable, and to women’s ability to control that male “love” through a skillful cultivation of beauty. One might be forgiven for refusing to believe this is love at all, that it is instead the creation of an intense desire for sexual pleasure due to the call of beauty. Observation shows that sex-generated “love” does not necessarily lead to compatibility for partners across a broad range of interests, and may occur between people who are, aside from sexual attraction, totally incompatible, with little in common, which is why the relationship often goes so badly when there occur gaps in the sexual game.

What I find interesting is that since the Middle Ages, as evidenced in Cornelia’s words, we have collectively conflated male love with sexual desire as if they are inseparable, and to women’s ability to control that male “love” through a skillful cultivation of beauty. One might be forgiven for refusing to believe this is love at all, that it is instead the creation of an intense desire for sexual pleasure due to the call of beauty. Observation shows that sex-generated “love” does not necessarily lead to compatibility for partners across a broad range of interests, and may occur between people who are, aside from sexual attraction, totally incompatible, with little in common, which is why the relationship often goes so badly when there occur gaps in the sexual game.

This raises the alternative notion of love based on compatibility, on what we might term ‘friendship-love’ which is not based solely on sexual desire – in fact sexual desire is not even essential to it though often present. Friendship love is about interests the partners share in common, a meeting of compatible souls and a getting to know each other on a level playing field. However aiming for friendship-love means women are no longer required to pull the strings of sexual desire as is practiced with beauty-based allure, which ultimately frees men and women to meet as equals in power and, with luck, find much in common to sustain a durable relationship.

[1] Robert Solomon, Love: Emotion, Myth, Metaphor, 1990 (p.62)

[2] Modesta Pozzo, The Worth of Women: their Nobility and Superiority to Men, 2007

[3] Nancy Friday, The Power of Beauty, 1997

You must be logged in to post a comment.