“The long march through the institutions is complete and

feminists now occupy pivotal positions of power and decision-making

throughout the world.”

Despite being a feminist-friendly book with some of the usual agitprop, Governance Feminism: An Introduction caught my eye because I have never seen an overt discussion of feminist institutional power by a feminist. It’s a topic classified taboo for academics and authors despite the effects of that power being experienced by peoples around the planet daily .

The book intrigued and perhaps even excited me for the prospect that a veil of denial and secrecy surrounding feminist power might be perforated for the first time.

The four authors of the work dubbed their topic Governance Feminism (GF), by which they mean “every form in which feminists and feminist ideas exert a governing will within human affairs.” This definition follows Michel Foucault’s definition of governmentality in which feminists and feminist ideas “conduct the conduct of men.” Governance Feminism is proposed as a new phrase, but it deserves mentioning that MRAs have been using the synonymous phrase ‘Feminist Governance’ for many years.

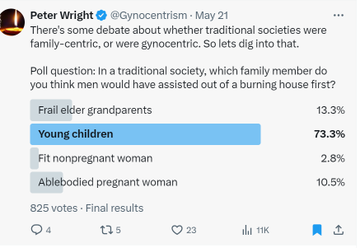

The work looks at feminist infiltration into positions of institutional and cultural power – the long march through the institutions that so many of us have been monitoring. Feminists have infiltrated the UN, World Bank, International Criminal Court, every layer of national governments, and further into universities, schools, NGO volunteer orgs, and in HR departments at most medium to large scale workplaces. Not to mention Twitter, Facebook, Youtube and other social media platforms where most of the world’s people communicate with each other. We would not be off base to say that feminist gatekeeping now regulates much of the planet, from top to bottom. They are everywhere.

But of course when questioned about holding such positions of power, feminists are quick to remind us that they still work for the “oppressed” sex and are thus justified in using positions of power to correct global imbalances. Ironically feminists consider power per se to be bad, a judgment rendering any admission of their own institutional power regulated by a strict taboo – for such an admission is akin to a Catholic nun who undertook vows of chastity, and being faced with admitting she is now in a sexual relationship. The authors tell:

The first and most persistent form of resistance we have encountered is based on an idea that governance is per se bad, often expressed as an understanding that our describing governance feminism is identical with denouncing it. We do not think it is a gotcha to say that feminism rules.”

The lead author Janet Halley admits elsewhere to being an occasional feminist – in other words a feminist if/when the need arises. Nevertheless her adoption of utopic feminist narratives is apparent throughout the pages, as for example when she characterizes feminism, and more specifically Governance Feminism as an “emancipatory project”:

Feminism is by aspiration an emancipatory project, and GF is one kind of feminists’ effort to discover pathways to human emancipation. In the process, GFeminists have been, in some cases, highly successful in changing laws, institutions, and practices, very often remarkably for the better. Just scan the canonical first-wave manifesto for change, the 1848 Seneca Falls Declaration of Sentiments,[4] for once-impossible, now well-established changes in the legal status of U.S. women: the right to vote; the rights of married women to form contracts, to sue and be sued, to acquire and manage separate property, to select their place of residence, to be criminally and civilly responsible for their own actions, to seek a divorce and to seek child custody on formally equal footing with husbands and fathers, and other powers formerly denied to them by coverture; to formally equal access to paid employment; to formally equal access to “wealth and distinction”[5] and to the professions; and to access to education.

These are all basic elements of a liberal feminist agenda for women. Women have devoted entire lifetimes to achieving them. None of them came easily. They are not complete emancipation, surely. But compared with lack of all franchise, coverture, and categorical exclusion from the public sphere and all but the most grinding and ill-paid work, they are immense achievements attributable almost entirely to GFeminist efforts. One reason to describe GF is to be clear about its immense emancipatory achievements.

I can hear the reader’s objections now, that Halley’s overview of three waves of feminism as ‘emancipatory’ is a laughable gloss over the violence, censorship and tyranny perpetrated throughout that history. No doubt Halley is here giving a mandatory nod to the narratives of her more powerful “sisters” in order to avoid a backlash.

Framing feminist aspirations as emancipatory, and not as an urge-to-power by ruthless gender-ideologues, softens the tyrannical use of power, painting instead a soothing pastel picture. Said more directly, feminist use of power has to most observers been far more tyrannical and destructive than this glowing characterization reveals. With that in mind the authors might equally have characterized Governance Feminism as unadulterated power-seeking (ultimately for women) and been more on point.

To be fair the authors do go on to tackle some of the excesses of Governance Feminism after their apparently mandatory hand kissing of feminist theorists, and this deeper critique is where the true value of this book lies. The authors admit that many feminist visions of “emancipation” have been left at the station when various governance trains took off, confirming that the ‘“selective engagement” of feminist ideas into governmental power has left some diamonds in the dust.’

Further, they state;

In our view it has also done some damage: some governance feminist projects strike us as terrible mistakes; others have unintended consequences that are or should be contested within feminist political life. As some Governance Feminist projects become part of established governance, we find ourselves worrying about them more, or differently, than we did when they were unorthodox, “outsider” ideas. We are, therefore, inviting a robust discussion within feminism and between feminism and its emancipatory allies about which elements are emancipatory and which may, after all, be mistakes. [italics mine]

The authors go on to critique a number of these ‘mistakes,’ while remaining at times uncritical about assumed feminist successes. As touched on above, Governance Feminists also go to great lengths to hide their grasp on power, while taking every opportunity to exaggerate and demonize male uses of power:

Gender mainstreaming has located feminists in many organizations, from the UN to college administrations, almost always as bureaucrats. Here they wield not judicial power, not the sword of punishment, but the more fine-grained power of administration. Gender mainstreaming, which aims to universalize feminist ideas in governance and convert every governmental entity into a branch of Governance Feminism, paradoxically produces gender specialists.”

For most readers this quote encapsulates the danger of feminist power. Feminist ideologues have been inserted into every institution around the globe as gatekeepers dictating who does/doesn’t get employed, get assisted, financed, approved, credentialed, included, heard and so on. It can even descend to who gets food aid, who gets to rent a house in a scarce rental market, or who gets a job as a cleaner.

As an example, Jordan Peterson recently talked about HR departments at workplaces serving as foci for the feminist social manipulations. This development is insidious because the practice is hidden in supposedly menial bureaucratic positions, ones that just happen to wield pivotal power over the work-lives of citizens and the associated family outcomes – not to mention the outcome of amplifying gendered expectations and conventions that inevitably get instituted culture-wide through this process of rewarding or punishing via biased bureaucratic decisions. With this in mind it’s no exaggeration to call feminists social engineers who have succeeded in running the world.

Some years ago I read a paper on the topic of “administrative discretion” which refers to the flexible exercising of decision-making allowed to public administrators. The discretionary opportunity is made available by the wiggle-room in the bureaucrat’s code of practice, and she or he uses that to deliver preferred – and often unfair – outcomes. The use of administrative discretion typifies the modus operandi of Governance Feminism, which is utilized to implement a radical feminist ideological agenda through all levels of society. Feminism-inspired women are increasingly dominating HR roles, and as revealed by teacher-preferencing biases in elementary schools they are exploiting administrative discretion to favor females over males.

Janet Halley lays much of the blame for the failures of Governance Feminism at the feet of two forms of feminism that form an operational alliance: Power Feminism (PF) and Cultural Feminism (CF). The book provides a useful overview of both, stating that they have formed an unholy alliance that came to dominate the internal battle for supremacy between different ‘feminisms.’ Power and cultural feminism meld into each other or appear side by side, writes Halley, and together they are frequently dubbed Dominance Feminism. She adds that Dominance Feminism finds male domination in two distinct forms: in the false superiority of male values and male culture, and in the domination of all things Female by all things Male:

American dominance feminism is a top-down, bottom-up model of M/F relations: there are perpetrators (men) and victims (women); people with an individualist ethic (men) and people with an ethic of care (women); people feminists advocate for (women) and people they accuse (men). This model of right and wrong is highly assimilable to criminal law and tort law frameworks. Thus the very visible elements of Governance Feminism that use the penal powers of the state to “end” sexual violence in all its forms are saturated with dominance feminist ideas. Especially where power feminism makes its influence felt, it makes sexuality the core of the problem: dominance feminist thinking places sexual wrongs front and center, and assimilates other seemingly nonsexual wrongs to sexual ones.

This is, we think, a manifestly narrow, crabbed, and even paranoid view of the gender order in the United States, and it is hospitable to quite ethnocentric, neocolonial construals of the gender order prevailing in the global South. It is remarkably indifferent to distributional consequences. Why does it play such a large role in Governance Feminism today?”

In Chapter 3. Halley discusses Governance Feminists’ need to reflect on generating, owning, and critiquing their own governance power, which as mentioned above is hamstrung by feminism’s denouncement of power structures combined with its own denials about both possessing and wielding real power.

When the authors first encouraged the sustained study of Governance Feminism in 2006, some feminists told them that “they simply did not understand how marginal and fragile feminist gains in state and near-state power really were… If some feminist ideas and interests had managed to find their way into law, these were crumbs from the table, compromises with patriarchy on patriarchy’s terms not worthy of the name “feminist,” tiny fragments of the full feminist agenda, which was not merely to ride along on the back of power but to transform it.”

Such a response is breathtaking in its denial, and I would add predictable, leading the authors to assert that not only do feminists hold such world-changing power, they need also to ethically critique their use of it:

We think such acts of public critique are absolutely essential now that feminists and feminist ideas are so firmly embedded in legal institutions and legal power.[25] But they can be costly: insider-insiders often feel compelled to attack any feminist who does it, at the very least by depriving her of her insider credentials and her insider job and at the very most by marshaling major institutional resources to discredit her and her ideas, defund her projects, and leave her constituents out in the cold.”

In the final chapter Halley implores Governance Feminists to develop an ethic of responsibility; to both admit to the power they preside over, assess its impact both negative and positive, and own the outcome. This lofty appeal is frankly laughable when considering the ideological agendas and unethical practices that Dominance Feminists are known for. Asking them to take a more ethical approach is as likely of success as asking Mao Zedong to develop an ethic of individual liberty and a policy of free-market capitalism.

Antifeminists around the world have a very different suggestion to that of going hat in hand imploring Dominance Feminists to show more ethical and considerate behavior. Their alternative is to shine a harsh light on the moral corruption of feminist ideologues, and work to neutralize their destructive programs via effective counter-activism. The antifeminist counter-movement is in full career and I’m certain that Governance Feminists around the world are already feeling the heat. Halley’s book contributes to that insurgency move, perhaps unwittingly, by demonstrating just how much power these ideologues have been wielding. The book is therefore useful in that it speaks the unspeakable… the cat is finally out of the bag.

The authors conclude by mentioning a second volume is in process titled Governance Feminism: Notes from the Field, which will provide case studies describing and assessing national, international, and transnational Governance Feminist projects by a range of feminists engaged in building them. No longer operating in the shadows, Governance Feminists are now being scrutinized in broad daylight…. and with that move they will have a lot of explaining to do for their transgressions.