By Robert Franklin

On reading my last post, I realized that I’d glossed over an issue that I should have addressed. So, dear reader, mea culpa.

I too hastily said that feminism, from its origins in the mid-19th century to today, has urged the abandonment of sex roles. That’s not completely accurate. Feminism has always urged society to grant women the freedom to step outside of their traditional role, but has been less enthusiastic about men’s doing so. At least until recently.

Feminism has been astonishing successful; it’s achieved far, far beyond anything its intellectual underpinnings merited. Feminist analysis of society, power and male/female relationships has always been at odds with basic facts and should long ago have been laughed out of serious public discourse. But that hasn’t happened and, to the contrary, basic articles of feminist faith have been incorporated into everything from statute law to our “understanding” of sex, the workplace, much of history and more.

So how did something so intellectually bankrupt come to have such a powerful influence on our society?

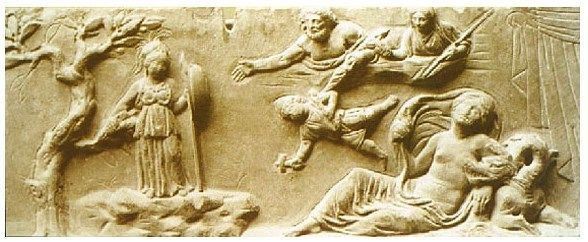

The answer is traditional sex roles. Metaphorically, when women screamed “Help!”, men came running to their rescue. Feminism has always relied on men, particularly members of dominant male hierarchies, a.k.a. power elites, to play the role of the knight on the white charger, St. George versus the dragon. So feminists have always played the maiden in distress, the better to recruit male power to their cause. That explains why feminists so often describe women as helpless victims of the most minor, everyday events and practices, a phenomenon remarked on by countless commentators. Why appear strong, when the appearance of weakness works so well?

Why has it worked?

Females have always been the protected sex. That was appropriate as long as human survival was in question, as it was for countless millennia. So men took on that role and do so to this day; evolved biology powerfully shapes behavior, so the mere fact that we no longer live in a world fraught with the perils faced by hunter-gatherer societies doesn’t mean we’ve abandoned the behaviors on which we relied for so long to survive. Remember the YouTube videos from several years ago showing a man in a public place loudly berating his female companion? Complete strangers – all of them men – intervened to make sure the woman wasn’t hurt. But when the same couple, both of them actors, switched roles and it was the woman not only shouting at the man, but hitting him, no one lifted a finger. Passersby barely glanced at the scene.

The journalist Dorothy Dix understood the dynamic perfectly. She agitated for women to be allowed to serve on juries. Her reason? Because all-male juries, when faced with a lachrymose female defendant accused of murdering her husband, too often voted to acquit. Dix understood that female jurors wouldn’t be so easily manipulated, so justice for male victims demanded that women participate in judging female defendants.

Feminism’s dark genius was and is to harness that male protective instinct for its own goals. So the Declaration of Sentiments in 1848 was, among other things, one long cry for help – help with rights, marriage, divorce, property, etc. So was the demand for the vote and later the Tender Years Doctrine, obtaining credit in a woman’s name, and the like.

Needless to say, many of the goals of feminism were, certainly by the standards of today, perfectly legitimate. Male-dominated power structures were right to accede to many of their demands. But, whether the demands were legitimate (e.g. the vote) or not (exemption from military conscription, the Tender Years Doctrine), the dynamic was the same. Women cried “Help!” and men “rode to their rescue.”

More recent events make that dynamic painfully clear. Indeed, it’s informative to view today’s feminism as simply testing the limits of the male inclination to protect. Perhaps air-conditioning in office buildings constitutes patriarchal oppression that “the Patriarchy” needs to change. That garnered ridicule, but little traction. What about “free bleeding,” i.e. abandoning tampons as more masculine oppression? A non-starter.

Those “issues” may seem trivial, but nevertheless illustrate that the dynamic, i.e. testing to see if male power will respond to a cry for help with corrective action, continues. Non-trivial issues demonstrate the same.

For example, we’ve known for decades that women are at least as likely as men to commit domestic violence and, since the 1970s, the male powers that be have lavished attention and money on female victims. But that same male power has always turned a blind eye to male suffering and female perpetration.

Likewise, due process of law has been gravely compromised in response to feminists’ demand that more men go to prison when women cry “Rape!” Every acquittal of a man accused of sexual wrongdoing is greeted with feminist outrage, regardless of the weakness of the case against him (see, e.g. the case of Gian Ghomeshi). And academic institutions and male-dominated businesses rush to fire powerful men on the mere accusation by a woman of even minor sexual impropriety. When writer Stephen Galloway was hounded out of his tenured position at the University of British Columbia, women levelled the accusations and men in the university’s power structure kicked him off campus and shunned him socially long before it was revealed that he’d done nothing wrong.

In short, the helpless woman/knight on the white horse dynamic is alive and well and feminists know it. Feminist success depends on it and always has.

Therefore, the fight to turn back the worst depredations of feminism is simultaneously a fight to turn men from their traditional ways of thinking about and acting toward women. As long as men in power respond to feminist complaints like chivalrous knights, feminists will continue to push for more and more and more. Why wouldn’t they?

Until then, intellectual distortions blight the landscape of public discourse. When feminists don the mask of the helpless, victimized woman in order to stimulate the savior response in men, while also arguing that gender is a societal construct that must be abolished, cognitive dissonance is born. I strongly suspect that the former cannot beget the latter, that using sex roles to abolish sex roles will never succeed. Perhaps it’s not intended to. Perhaps Little Nell and her rescuer are perfectly happy with their roles.

After all, as I established several posts back, feminism has always been about “more for us,” i.e. more power, more money, more rights, more privileges for women. If traditional sex roles provide that “more,” and they do, then feminists would be foolish to do anything but continue the drama that pays so well, until someone mercifully brings the curtain down.

In the meantime, the ironies pour on us like a biblical flood.