Most by now will have heard the name Jordan Peterson, who has become quite the internet sensation as he tackles the excesses of postmodern philosophy and it’s negative impact on society. His fight against the deconstruction of traditional cultural forms, along with the existential vertigo and nihilism that inevitably follow it are commendable. However there’s a question mark over what Peterson deems to replace that postmodernism with, which I’ll get to in a moment.

Peterson works largely, though not exclusively, with Jungian terminology – especially with what Jungians term the ‘archetypal patters’ of human behaviour. Carl Jung was among the first to document universal patterns of behavior among humans which he called archetypal patterns, which he later gave discreet titles such as the child archetype, father archetype, mother archetype, and so on. Jung identified literally hundreds of such archetypes and discovered that classical mythologies also tended to record these archetypal themes in story form.

Jung believed that all people perceive the world through archetypal filters of one kind or another, and are often unconscious of the fact they are perceiving the world through a limited archetypal lens.

With that brief description of archetypes I come back to the question of what Jordan Peterson wants to replace postmodernism with. Does he want to replace it with what was there before it, a wide variety of archetypal forms? The answer to that appears to be no, he has a much more simplistic prescription to fill the void: that men become heroes and women become mothers.

After all the good of cautioning against the excesses of postmodernism, Peterson would unwind it by advocating an equally excessive cult of motherhood as the necessary alternative. He is caught by the spell of what Jungians refer to as the Great Mother Archetype, and doesn’t realize he’s caught.

The overwhelming amount of emphasis and air time he gives to discussing good mothers, bad mothers, the Great Mother, Oedipal mother, devouring mother, nurturing mother and so on far exceeds the airtime he gives to other themes. Mentioning career women occasionally (often in the negative) doesn’t make the emphasis any less obsessive.

In the early pioneering days of Freud and Jung there was a huge fad of interest in parental figures, especially the mother. Theory has since moved on from mothers and the mother archetype, but Peterson appears trapped there compliments of his fascination with Jungian literature. This is the Achilles heel of his pitch for improved gender relations and it deserves unpacking.

The first thing we need to know about the Mother Archetype is that it is linked to her archetypal son – The Hero.2 In myths and stories around the world we read of Mamma’s hero-son moving through the world slaying dragons, a theme Peterson specializes in discussing.

The possession of Peterson’s mind by the theme of the Great Mother and her son The Hero compels him to ask young men to lift heavy weights, and ask young women to be mothers – great mothers. Anyone with a strong understanding of archetypal psychology will see immediate problems in this proposal.

Here’s an excerpt from post-Jungian James Hillman which I think captures the issue well:

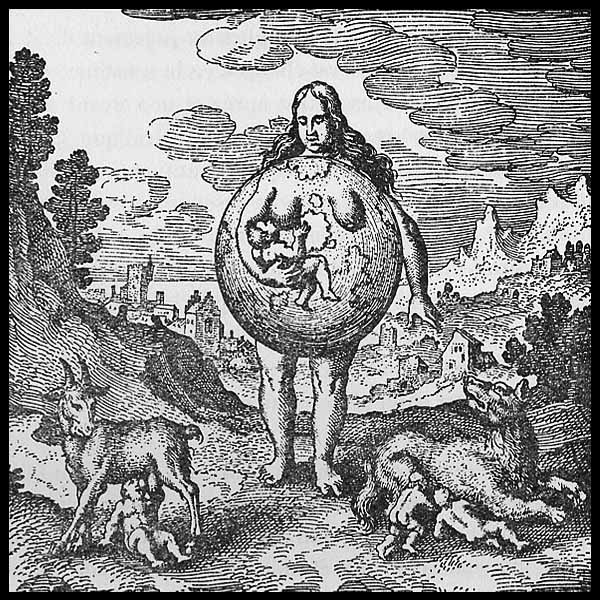

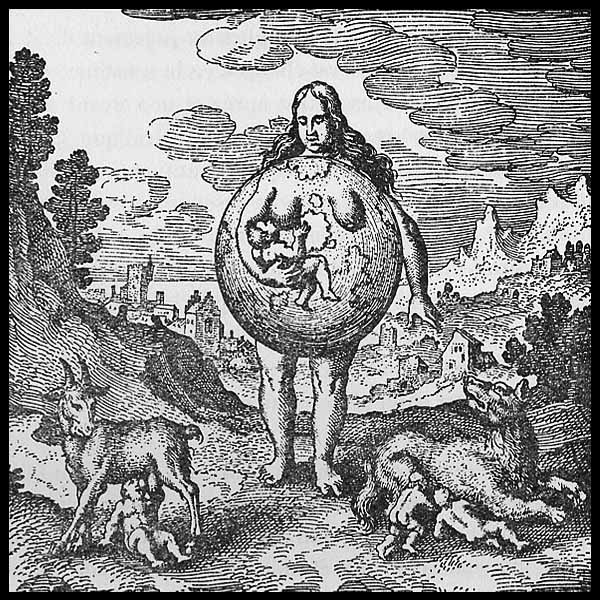

In their early discoveries, Freudian and Jungian psychologies both were dominated by parental archetypes, especially the mother, so that behavior and imagery were mainly interpreted through this maternal perspective: the oedipal mother, the positive and negative mother, the castrating and devouring mother, the battle with the mother and the incestuous return. The unconscious and the realm of “The Mothers” were often an identity. Through this one archetypal hermeneutic, female figures and receptive passive objects were indiscriminately made into mother symbols. What was not mother! Mountains, trees, oceans, animals, the body and time cycles, receptacles and containers, wisdom and love, cities and fields, witches and death – and a great deal more lost specificity during this period of psychology so devoted to the Great Mother and her son, the Hero. Jung took us a step forward by elaborating other archetypal feminine forms, e.g., the anima, and I have tried to continue in Jung’s direction by remembering that breasts, and even milk, do not belong only to mothers, that other divine figures besides Maria, Demeter, and Kybele have equally important things to say to the psyche and that the women attendant on Dionysus were not turned into mothers but nurses. Like those frescoes of the madonna Church which conceals a congregation under her billowed blue skirts, the Great Mother has hidden a pantheon of other feminine modes for enacting life.1

With his monotheism of the Mother, Peterson narrows the prescription for young men and women, this in contrast to Jung for whom the archetypal possibilities for a human life are ‘polytheistic‘ (ie. multi-optional and varied); thus living out the Mother and Hero archetypes alone – Peterson’s preferred template – reduces that variety to singular options.

Asking all young men to be worldly heroes, to lift heavy weights to compliment the maternal principle, and asking young women to be mothers when they may not be suited to motherhood at all, limits the possibilities dramatically and may fly in the face of a person’s calling to be something else entirely.

In order to get past this mother-monotheism we need to lift Madonna’s skirt to allow all the many archetypal forms to walk out and stand independently on their own two feet. By relativizing the Mother Archetype, by removing that word “Great” that appears before it, we allow it to be just one archetype among many, no more or less important than the rest.

Many men want to be heroes, and women mothers. However there’s a problem resulting from what’s left out of that picture. The omission of other archetypal styles and perspectives likely leads people away from things they might be better suited to. For example some men are not called to be worldly heroes and don’t want to be – they might be spontaneous Peter Pan’s, introverts, gay men, Zeta males, bachelors or intellectual explorers. Likewise women might not be first and foremost identified with their wombs and kitchens – they might have a strong desire to be childless and perhaps to pursue some other life calling; to study, to have a career, help the homeless, or whatever.

It’s insufficient to argue that “mothering has its basis in biology” and thus the Mother Archetype is the most important archetype to push. All archetypes have their basis in biology, that’s Jungianism 101 and therein lies the problem: Peterson talks only about mothering as biologically based but does not grant the same basis in biology for the other archetypal patterns women might enact.

The mother Goddess Demeter is not the only Goddess…. there are others like Artemis (a freewheeling virgin huntress); Athena (a virgin Goddess focused on civic responsibility); Aphrodite (Goddess of beauty, sexual pleasure and love); Hestia (a virgin Goddess of the hearth); or Hera (Goddess of social power and status) just to mention a few. Psychiatrist Dr. Jean Shinoda-Bolen elaborates some of the many feminine archetypes, the ones that Peterson neglects, in her book Goddesses in Everywoman: Powerful Archetypes in Women’s Lives.

Many of these archetypal figures in myth were not primarily mothers, but nonetheless the biological impulses that give rise to their patternings are equally as valid as those underpinning mothering.

To underline the point more starkly we can say that even the destructive spectacle of feminism that Peterson rightly resists is a biologically-based archetypal pattern.

To summarize, the danger in Peterson’s advice is that it narrows the possibilities too much, and too forcefully in favor of Mother and her Hero son.2 Moreover, many men have become tired of the onerous demands placed on them by traditional gender roles, and who can really blame them?

Traditional gender roles were workable when held in balance, with careful reciprocity guiding the arrangement. However in modern society the contractual emphasis on reciprocity has gone by the wayside in favor of extracting all you can from the other person and from the relationship. That makes traditional relationships potential places of exploitation and likely failure.

Yearning to return to better models of the past doesn’t guarantee we’ll get them, as so many people discover. What we get instead are onerous gendered-expectations and demands with little payoff – or worse asset loss, parental alienation, false accusations and public shaming, not to mention the psychological sequelae that comes with it.

For men, such mother-serving heroics serve to further an already lopsided gynocentric culture, one asking men to put themselves into the service of marriage and womankind in an environment that is unlikely to provide much if any reciprocal payoff — for women long ago cast off society’s demand that they play the role of mother and dutiful wife, and men are now seeing fit to do the same.

Men’s Rights Activists have long known that postmodernism, feminism, and marxist SJW’s are bankrupt. That’s what we fight. Likewise we know that traditional gynocentrism is bankrupt. This article attempts to show that Peterson too understands the bankruptcy of postmodernism, feminism, and marxist SJW culture, which he describes articulately and with passion….. but then proceeds to fumble for a working model to replace it. For him the replacement is a return to traditional stereotypes of mothers, marriage and women-serving heroes. Traditional gynocentrism. The problem today is that neither women nor men are willing to define themselves solely by relation to the opposite sex, which they view as an exercise in exploitation and control…. so Peterson’s solution simply doesn’t work for many people of today.

MRAs have elaborated one solution in the Zeta / MGTOW life orientation that doesn’t view male identity primarily on the basis of how it benefits the opposite sex. And as part of that adjustment many men who want relationships with women – the red pill kind – are beginning to approach them as relationships between peers (Marc Rudov), as intimate friendships, or as forms of non-gynocentric traditionalism…. or they may frame them as something else entirely. What they are doing is weaving a middle path between Scylla and Charybdis, and refusing to swap one poison for another.

Sources:

Videos by Jordan Peterson.

Analysis of Sleeping Beauty

Is it right to bring a baby into this terrible world?

The Oedipal Mother in a South Park Episode

The Positive Mother Gives Birth to the Hero

The Failed Hero Story vs The Successful (Freud vs Jung)

The overprotective mother or ‘how not to raise a child’

Reference:

[1] Hillman, J. Abandoning the Child, in Mythic Figures, Vol 6. Uniform Edition

Notes:

[2] There are a number of variations on the hero theme, as detailed by Joseph Campbell in his book The Hero With a Thousand Faces. Campbell wasn’t a Jungian, and he was suspicious of many Jungian dogmas: “I’m not a Jungian! As far as interpreting myths, Jung gives me the best clues I’ve got. But I’m much more interested in diffusion and relationships historically than Jung was, so that the Jungians think of me as a kind of questionable person.” [An Open Life: Joseph Campbell in conversation with Michael Toms].

When referring to the hero archetype as servant of “The Great Mother” I’m referring exclusively to the classical Jungian understanding of that term, and to Jordan Peterson’s reliance on same. The hero archetype in Jung’s writings is intimately bound up with the mother archetype (a man being a hero for mother / or fighting against the dragon mother, etc), a position that can be contrasted with Campbell’s focus which held that a hero’s journey need not imply mother whatsoever. For further reference, Jung’s mother-tied definition of the hero – ‘Mother’s Hero’ – is laid out in his Symbols of Transformation.

Regarding Campbell’s position, one poster on the Peterson facebook page helpfully clarified it like this; “The hero’s journey as described by Joseph Campbell begins by ‘Separation,’ the departure from the status quo. To me this personally I associate this to stepping out of and leaving the gynocentric view of the status quo.” This is a correct assessment of Campbell’s position, and it points to a true stepping off into the unknown, into a more gutsy hero’s journey as compared with stepping out into the world as ‘mother’s hero’ to do her bidding. As Campbell characterized it, the true hero journey entails leaving the mother-world behind and seeking atonement with the father.

See also: Jordan Peterson’s Map For Oedipal Men