Medieval Women Who Engineered The Rise Of Troubadour Poetry

In the medieval period, particularly in the 12th and 13th centuries, troubadour poetry flourished in the Occitan-speaking regions of what is now southern France, northern Spain, and parts of Italy. Troubadours were poet-musicians who composed lyric poetry, often centered on themes of courtly love, chivalry, and devotion, performed in aristocratic courts. Several prominent women, typically noblewomen or queens, played significant roles as patrons, sponsors, or inspirations for troubadour poetry, leveraging their wealth, influence, and cultural sophistication to foster this gynocentric tradition. Below are examples of notable medieval women who sponsored or popularized troubadour poetry, along with examples of the poetry or poets associated with them.

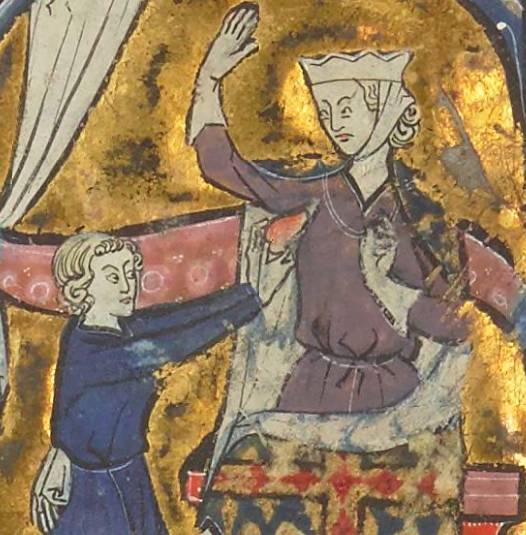

1. Eleanor of Aquitaine (1122–1204)

One of the most powerful and influential women of the Middle Ages, Eleanor was Duchess of Aquitaine, Queen of France (1137–1152), and later Queen of England (1154–1189). Her courts in Aquitaine and Poitiers were major centers of cultural activity, where she actively patronized troubadours and fostered the ideals of courtly love.

Contributions to Troubadour Poetry:

- Eleanor’s court at Poitiers became a hub for troubadours, where she encouraged the composition of poetry that celebrated “refined love of women” and chivalric ideals. She is credited with being a primary influence to spread the troubadour tradition from southern France to northern France and England.

- Her wealth and political influence provided financial support and prestige to troubadours, allowing them to compose and perform their works.

- Eleanor’s own life, marked by her beauty and political acumen inspired troubadour poetry, with some scholars suggesting she was the first major, idealized figure in the “distant lady” (domna) motif common in troubadour songs.

Examples of Poetry/Poets:

-

- Bernart de Ventadorn (c. 1130–1190): One of the most famous troubadours, Bernart is believed to have been associated with Eleanor’s court. His poetry often explored themes of unrequited love and devotion to a noble lady, possibly inspired by Eleanor herself. A famous example is his canso (love song), Can vei la lauzeta mover (“When I see the lark beat its wings”), which expresses longing and devotion:

Can vei la lauzeta mover

De joi sas alas contra·l rai,

Que s’oblid’ e·s laissa chazer

Per la doussor c’al cor li vai…

(When I see the lark beat its wings with joy against the rays of the sun, that it forgets itself and lets itself fall for the sweetness that goes to its heart…)

Impact: Eleanor’s patronage helped elevate troubadour poetry from a regional tradition to a pan-European cultural phenomenon, influencing the trouvères (northern French poet-musicians) and all later literary traditions.

2. Marie de Champagne (1145–1198)

Eleanor of Aquitaine’s daughter, Marie was Countess of Champagne and a key patron of the arts at her court in Troyes. She inherited her mother’s passion for romantic chivalry and courtly culture and was instrumental in shaping the ideals of courtly love.

Contributions to Troubadour Poetry:

- Marie’s court was a center for literary production, where she sponsored troubadours and trouvères. She is particularly associated with the codification of courtly love, as her court attracted poets and writers who explored these themes.

- She is famously linked to Chrétien de Troyes, a trouvère whose romances were influenced by troubadour ideals. Marie likely commissioned or inspired Chrétien’s romance Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart, which emphasizes the courtly love between Lancelot and Guinevere.

- Marie’s patronage extended to troubadours visiting her court, where they performed and composed poetry that aligned with her vision of refined, idealized love.

Examples of Poetry/Poets:

-

- Chrétien de Troyes (fl. 1160–1191): While not a troubadour in the strict Occitan sense, Chrétien’s works were heavily influenced by troubadour poetry, and he operated in Marie’s court. His romance Lancelot reflects troubadour themes of devotion and service to a lady:

[Lancelot] was so lost in thought of his lady that he did not hear or see anything… His heart was so wholly given to her that he no longer had power over it.

- Gace Brulé (c. 1160–after 1213): A trouvère associated with Marie’s court, Gace composed songs that echoed troubadour themes. His A la douçor de la bele saison (“In the sweetness of the beautiful season”) reflects the lyrical style of troubadour poetry, celebrating love and nature.

Impact: Marie’s patronage helped bridge the troubadour tradition of southern France with the trouvère tradition in the north, creating a broader cultural movement.

3. Ermengarde of Narbonne (1127/29–1196/97)

Viscountess of Narbonne, Ermengarde was a powerful feudal lord in her own right, ruling a key city in the Occitan region. Her court was a major center for troubadour activity.

Contributions to Troubadour Poetry:

- Ermengarde was a direct patron of troubadours, offering them financial support and a venue to perform their works. Her court in Narbonne was a gathering place for poets, knights, and intellectuals.

- She was celebrated in troubadour poetry as an idealized figure of beauty, wisdom, and generosity, embodying the domna (noble lady) central to the genre.

- Ermengarde’s patronage helped sustain the troubadour tradition during a period of political instability in the region, particularly during the Albigensian Crusade.

Examples of Poetry/Poets:

-

- Peire d’Alvernhe (fl. 1149–1170): A troubadour who dedicated poems to Ermengarde, praising her beauty and virtue. In one of his songs, he refers to her as a model of courtly excellence:

Domna, vostre pretz e vostre valor

Es tan grans que totz lo monz en parla…

(Lady, your worth and your valor are so great that the whole world speaks of it…)

- Raimbaut d’Aurenga (c. 1147–1173): Another troubadour associated with Ermengarde’s court, Raimbaut composed intricate love poetry, such as Escotatz, mas no say que s’es (“Listen, but I don’t know what it is”), which reflects the complex, playful style favored in her court.

Impact: Ermengarde’s support ensured that Narbonne remained a cultural stronghold for troubadours, even as political tensions rose in the region.

4. Azalais de Porcairagues (fl. late 12th century)

A trobairitz (female troubadour) and noblewoman from the region of Montpellier, Azalais was both a poet and a patron of other troubadours.

Contributions to Troubadour Poetry:

- As a trobairitz, Azalais composed her own poetry, contributing directly to the troubadour tradition. Her work is notable for its emotional overtures and personal perspective, celebrating women.

- As a patron, she supported other troubadours, hosting them at her court and fostering the exchange of poetic ideas.

- Her poetry often engaged with the conventions of courtly love, either adopting or subverting them to reflect her own experiences.

Examples of Poetry:

-

- Azalais is best known for her canso Ar em al freg temps vengut (“Now we are come to the cold time”), which laments the loss of love and the harshness of winter, blending personal emotion with natural imagery:

Ar em al freg temps vengut

Que’l gels e la neus e la fanha…

(Now we are come to the cold time when the ice and the snow and the mud…)

- This poem, addressed to another noblewoman, possibly Ermengarde of Narbonne, reflects the intimate and collaborative nature of the troubadour project among women.

Impact: Azalais’s dual role as poet and patron highlights the active participation of women in shaping troubadour poetry, both as creators and supporters.

5. Beatrice of Provence (c. 1229–1267)

Countess of Provence and later Queen of Sicily through her marriage to Charles I of Anjou, Beatrice was a prominent noblewoman in the Occitan region during the decline of the troubadour tradition.

Contributions to Troubadour Poetry:

- Beatrice’s court in Provence continued to attract troubadours, even as the Albigensian Crusade (1209–1229) disrupted the region’s cultural life. Her patronage provided a refuge for troubadour poets displaced by the conflict.

- She was celebrated in troubadour poetry as a mighty symbol of beauty and nobility, and her court maintained the tradition of courtly entertainment.

- Beatrice’s support helped preserve troubadour poetry in Provence during a period of political upheaval, bridging the earlier flourishing of the tradition with its later evolution in Italy and Catalonia.

Examples of Poetry/Poets:

- Bertran de Born (c. 1140–1215): A troubadour known for his sirventes (political or satirical songs), Bertran was active in the region and may have performed at Beatrice’s court. His poem Ges de disnar no·m cal vïanda praises the virtues of a noble lady, possibly inspired by Beatrice or similar patronesses.

- Peire Cardenal (c. 1180–1278): A later troubadour, Peire composed sirventes that critiqued the political and religious turmoil of the time, likely finding an audience in Beatrice’s court, which valued both art and political discourse.

Impact: Beatrice’s patronage helped sustain the troubadour tradition in Provence during a challenging period, ensuring its legacy in southern Europe.

6. Maria de Ventadorn (fl. late 12th century)

A trobairitz and noblewoman from the Ventadorn family, Maria was both a poet and a patron, closely tied to the troubadour tradition through her family and court.

Contributions to Troubadour Poetry:

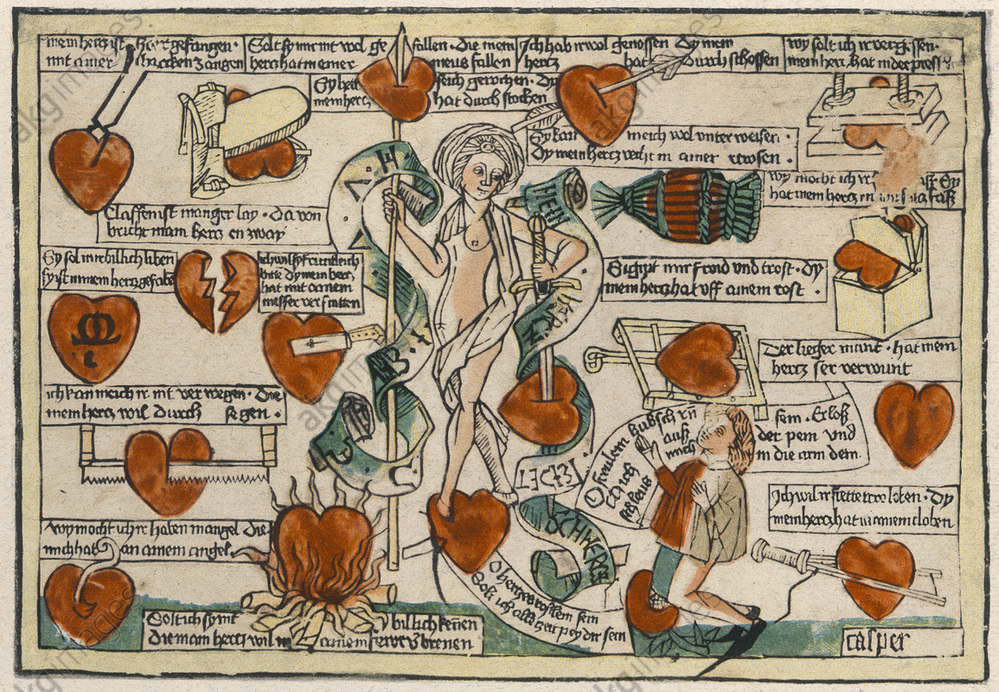

- Maria composed poetry that engaged directly with the conventions of courtly love, often in the form of tensos (debate poems) with other troubadours.

- As a patron, she supported troubadours at her court in Ventadorn, a region known for producing prominent poets like Bernart de Ventadorn.

- Her popularization of troubadour poetry, particularly through her debates, enriched the genre by introducing complex discussions of love and honor of men toward women.

Examples of Poetry:

-

- Maria is known for a tenso with Gui d’Ussel, in which they debate the nature of love and whether a lady should have equal status with her lover:

Gui, d’una re vos voill demandar:

S’om es en poder de sa druda,

Deu far so qu’ilh li comanda?

(Gui, I want to ask you one thing: If a man is in the power of his lady, must he do what she commands?)

- This poem reflects Maria’s active role in shaping the intellectual discourse around courtly love.

Impact: Maria’s contributions as both a poet and patron helped elevate the role of women in troubadour poetry, emphasizing their agency in the production of cultural and sexual conventions.

Summary

- Cultural Role of Women: These women, through their patronage, not only provided financial and social support but also shaped the entire genre and ideals of troubadour poetry. The concept of the domna, the idealized over-lady who inspires devotion, was often modeled on real noblewomen like Eleanor, Ermengarde, or Beatrice

- Legacy: The influence of these women extended beyond their lifetimes and into the present, as troubadour poetry inspired later literary traditions, including the Italian dolce stil novo and the works of Dante and Petrarch, and through to Victorian romance novels and arts today which continue to champion romantic chivalry and idealization of women.

Summary

Prominent medieval women like Eleanor of Aquitaine, Marie de Champagne, Ermengarde of Narbonne, Azalais de Porcairagues, Beatrice of Provence, and Maria de Ventadorn were instrumental in sponsoring and popularizing troubadour poetry. They provided financial support, hosted poets at their courts, and inspired works that celebrated courtly love and chivalric ideals. Their patronage supported poets like Bernart de Ventadorn, Peire d’Alvernhe, Raimbaut d’Aurenga, and others, while trobairitz like Azalais and Maria contributed their own voices to the tradition. Through their influence, these women shaped one of the most enduring literary movements of the Middle Ages, a movement which continued to evolve into the conventions known today as chivalry and romantic love.