Above is a painting of Frau Minne from Southern Germany, 1320-1330 ca. The image depicts the male lover presenting Frau Minne with his heart which has been pierced by three arrows. There are two German inscriptions with the image, the first of which translates as “Lady, send me solace, my heart has been wounded,” while the second reads as “Gracious Lady, I have surrendered.”

Frau Minne (vrouw minne) is the personification of courtly love from German Middle Ages. She is frequently addressed directly in Minnesang poetry, usually by a pining lover who is complaining about his state of spiritual suffering.

She is often referred to as the “Goddess” of courtly love, which is differentiated strongly from other kinds of love such as Christian agape as embodied in the figure of Jesus. To make the distinction clear, courtly & romantic love is understood as passion, whereas Christian and Buddhist love is understood as compassion.

A rare allegorical painting of ca. 1400 (see figure 1), discovered in a guild house in Zurich in 2009 shows Frau Minne presiding over the suffering of male lovers who are having their hearts torn from their breasts. In this cruel scene Goddess Minne, the mistress of love, sits on a throne consisting of two men. She has just torn out the heart of a man to her left which she holds in her hand, while she is already cutting open the chest of another man to her right to rip his heart out.1

Goddess Minne sits on a throne made of two men, while preceding to rip out the hearts of men in love.

Courtly and romantic love involves the deployment of superstimuli, including titillating courtship rituals such as male chivalry toward fetishized ladies that in many ways resembles the power dynamic of sado-masochistic practices. Nevertheless, this still forms the basis of a spiritual practice, and the originators of this religion stated that if you were not suffering, you were not experiencing the fullness of the goddess’s divine power. Such passion-inducing love contrasts with other kinds of love as mentioned above, such as friendship love, parental love extended to children, or that of Christianity or Buddhism which focuses on human compassion.

In Figure 2. (below) N. R. Kline states, “The central section depicts Frau Minne as she presides over a couple that seeks her advice. The bearded lover is presumably the author of the text telling of his plight at having to leave. He points to his chest, with text leading from his mouth that reads: ‘st hat dahin’ (you have my heart [in your hand]). The woman to whom he speaks holds the heart to which the man presumably refers. After a series of entreaties his lady finally gives him her blessing and, in the course of the conversation from one panel to the next, the lady offers her fidelity and the man promises the same. On the cover, winged and crowned, Minne, as both judge and witness, sits on a subjugated crouching man as her throne, a visual metonym of triumphant female power. There are no symbols of the religious trappings of betrothal and marriage.”2

Figure 2: Minnekästchen (cover), wood, end of 14th c. (?), Decorative Arts Museum, State Museums, Berlin.

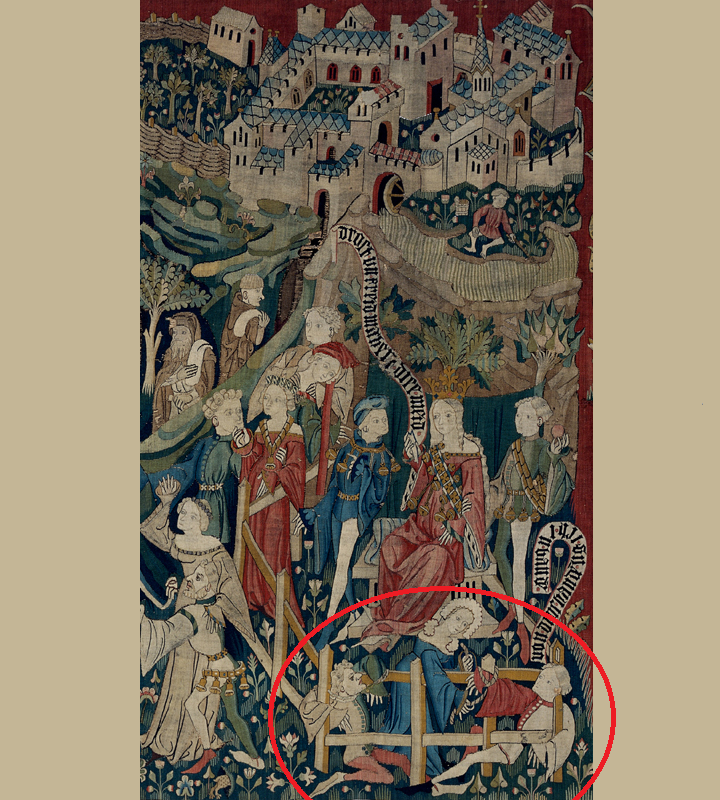

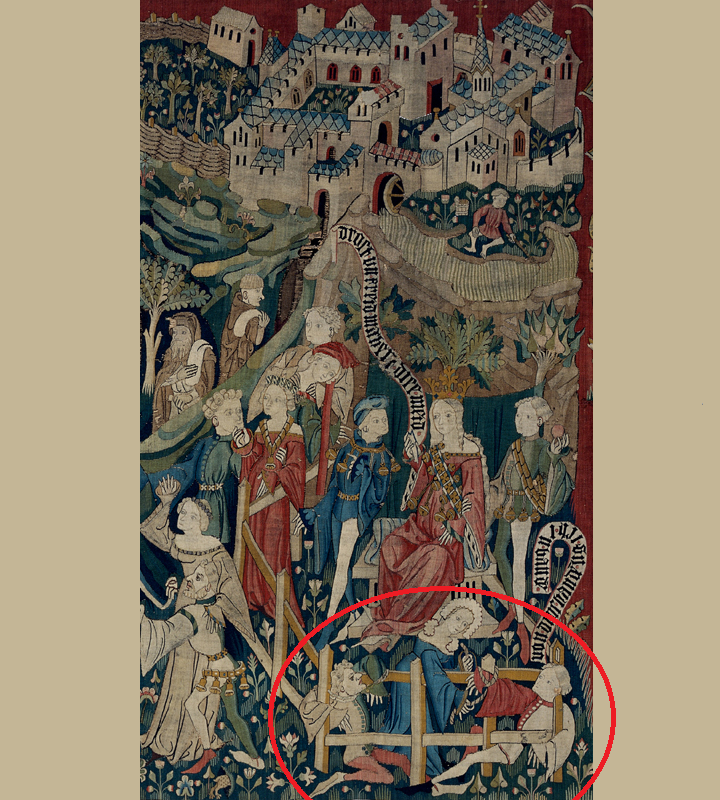

The Rhenish tapestry below (1400-1425) shows a young woman tying both an old man and a young man to the fence that encloses the court of Frau Minne (see highlighted detail). Alison G. Stewart explains the scene as follows; “This tapestry illustrates the already well-known concept of Love as an enslaver of men of all ages. In particular, it points to the idea that women have the power to reduce interested men to slaves or fools, an idea seen as early as the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries in depictions on Minnekästchen (small ornamental boxes which served as love tokens), on capitals, and in frescoes of Aristotle and Phyllis or Samson and Delilah.” 3

Figure 3: Detail from Courtly Love Games (Spieleteppich), tapestry, circa 1400. Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg.

According to Johan Winkelman of the University of Amsterdam, Frau Minne is identified (see figure 4) with a crowned vulva carried aloft by servile, erect penises, thus depicting Minne by her most extreme elemental power.4

Figure 4: Badge displaying three phalli bearing a crowned vulva in a procession, 1375-1450, found in Brugge (Van Beuningen family collection, inventory number 652)

As mentioned in a previous essay, romantic love began as a code of conduct among the aristocratic classes of the middle ages. However, the trend made its way by degrees eventually to the middle classes, and finally to the lower classes, and ultimately broke class distinctions altogether in the sense that all Western peoples became inheritors of the customs of romantic love regardless of their social station. This breaking of class barriers is marvellously rendered in the painting below by Hans Koberstein (figure 5), who portrays Frau Minne leading a helpless throng of individuals consisting of royalty and pauper, young and old, who are equally held under her sway.

Figure 5: Frau Minne smashes all class barriers, making rich and poor alike suffer from love sickness (Painting by Hans Koberstein, Germany, 1864-1945)

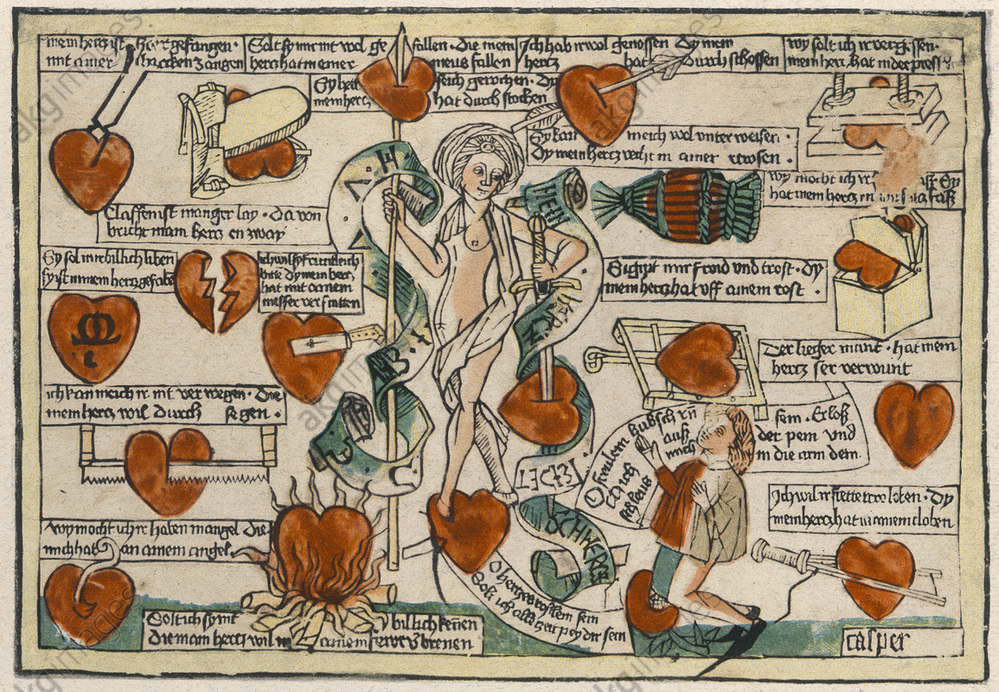

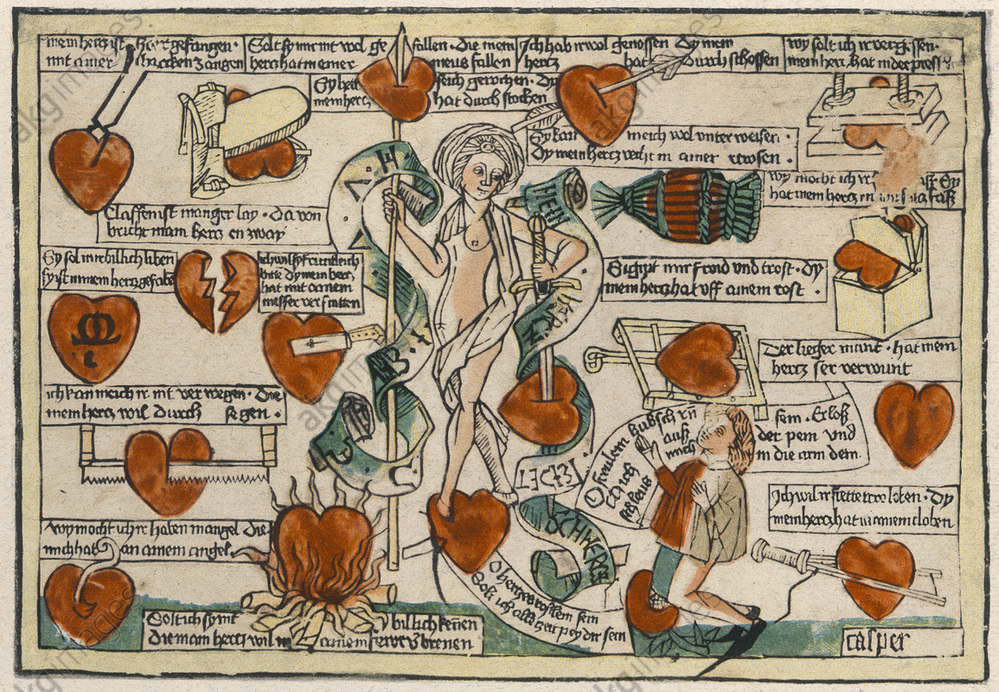

A 15th century depiction “The Power of Frau Minne” (figure 6, below) captures the pain and pathology so widely known to be part of the courtly and romantic love experience. The pathology associated with romantic love is so disturbing, in fact, that clinical psychologist Dr. Frank Tallis has written a book detailing the sickness associated with it based on his extensive clinical experience:

Obsessive thoughts, erratic mood swings, insomnia, loss of appetite, recurrent and persistent images and impulses, superstitious or ritualistic compulsions, delusion, the inability to concentrate—exhibiting just five or six of these symptoms is enough to merit a diagnosis of a major depressive episode. Yet we all subconsciously welcome these symptoms when we allow ourselves to fall in love. In Love Sick, Dr. Frank Tallis, a leading authority on obsessive disorders, considers our experiences and expressions of love, and why the combinations of pleasure and pain, ecstasy and despair, rapture and grief have come to characterize what we mean when we speak of falling in love. Tallis examines why the agony associated with romantic love continues to be such a popular subject for poets, philosophers, songwriters, and scientists, and questions just how healthy our attitudes are and whether there may in fact be more sane, less tortured ways to love. A highly informative exploration of how, throughout time, principally in the West, the symptoms of mental illness have been used to describe the state of being in love, this book offers an eloquent, thought-provoking, and endlessly illuminating look at one of the most important aspects of human behavior.5

Figure 6: “The Power of Minne,” – an allegorical depiction of women’s power over men’s hearts (Broadsheet woodcut, 15th century by Master Casper von Regensburg, Berlin, SMB, Kupferstichkabinett)

References:

[1] Frau Minne hat sich gut gehalten, 2009

[2] Naomi Reed Kline The Proverbial Role of Frau Minne: ‘Liebe macht Blind’ – Or Does It? in The Profane Arts: Norms and Transgression, Brepols (2016)

[3] Alison G. Stewart, Unequal Lovers: A Study of Unequal Couples in Northern Art, (1978)

[4] The world upside down. Secular badges and the iconography of the Late Medieval Period, in Journal of Archaeology in the Low Countries 1-2 (November 2009) “Malcolm Jones has pointed out that the crowned vulva on this badge should be interpreted as a persiflage on Mary (Jones 2000, 100-101), whilst Johan Winkelman, Emeritus Professor of Historical German Literature at the University of Amsterdam, identified the vulva as an extreme depiction of Vrouw Minne (i.e. the Middle Dutch equivalent of Venus, a symbol of lust) (Winkelman 2002a, 231). According to the attributes with which she is associated, Vrouw Minne, portrayed as a vulva, is the counterpart symbol of Mary, just like Eve in the above-mentioned miniature from the Book of Hours of Catharina van Kleef.”

[5] Love Sick: Love as a Mental Illness, by Frank Tallis – overview on Goodreads