A Male-Positive Introduction to the Victorian Manhood Question

By Dennis Gouws

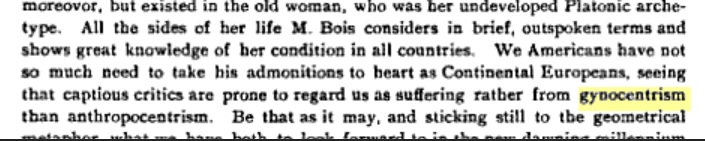

The new male studies offer an affirmative alternative to traditional gender scholarship on boys and men. Unlike pervasive men’s-studies research, male studies inquiries are essentially male positive: their methodologies not only celebrate men who embody different masculinities, but also critique —and suggest strategies for overcoming— systemic inhibitors of masculine affirmation. Misandric constructions of masculine identities in gynocentric educational environments have resulted in males experiencing serious education deficits. This paper reports on a qualitative study undertaken in a British-Literature course on Victorian Manhood that offered students a male-positive approach to understanding the texts and their contexts and that solicited their written feedback on what they had learned from this experience.

The Victorian Manhood Question

Since the fourteenth century, men’s identities and conduct had been conceived of as a question of manhood; manhood had elucidated men’s difference from women and boys, men’s sexuality, men’s duty to society, and men’s courage. Manhood, moreover, had traditionally been contingent, a reputation that a man had to attain and maintain. In newly industrial nineteenth-century Britain, the manhood question considered traditional and new ways a man might grow into and sustain a meaningful, productive, and commendable type of manhood.3 My Victorian manhood question course examined these traditional and new ways of attaining and sustaining manhood within four topics: first, contending manhood identities in George eliot’s Adam Bede,( a novel set in the early nineteenth century when proto-industrial manhood began to contend with gentlemanliness as the measure of a man); second, industrial manhood (which examined debates by Thomas Carlyle, Thomas Babbington Macaulay, and Karl engels the consequences for men of submitting themselves to be labor as manufacturing tools); third, artistic manhood (which examined works by John ruskin, Matthew Arnold, D. G. Rossetti, Walter Pater, and Oscar Wilde that explored art’s role as moral edifier, social unifier, or antagonist to industrialization), and finally, imperial manhood (including W.E. Henley’s “Invictus” and Kipling’s “If—” which encouraged male stoicism in the name of empire building). Throughout the course students were encouraged to consider the extent to which the question of manhood had changed or stayed the same for men in the twenty-first century.

What Students Claim to Have Learned from the Course

I offered an end-of-the semester summative assessment that asked the twenty-two participating students to write about their most important lesson, concept, or experience gained from the course, and I used their papers as the basis for a qualitative study of what they had learned from this male positive educational experience. To encourage the students to express themselves freely, I graded this assignment only on whether the work had been satisfactorily completed, not on what was reported: students who adequately completed the assignment were given full credit for it. For the study I grouped their papers into three categories: first, those safe, stock responses that merely reiterated either points made in class or traditional gender-studies commonplaces (five students chose to write those); second, those papers that demonstrated their authors’ ability to undertake a male-positive approach to understanding manhood in both the texts we read and broader socio-historical contexts (thirteen students wrote such papers); and finally, those works that bore witness to their authors’ decision to embrace aspects of a male-positive philosophy, one that celebrates masculinities, critiques their construction, and potentially resists pervasive gynocentric and misandric representations of men (four students’ work provided such evidence). I will only discuss those student responses from the latter two categories because they offer clear evidence that this course successfully enabled more than three-quarters of the students to understand and apply the salient concepts of the course to the literature, its respective contexts, and their lives. I offered an end-of-the semester summative assessment that asked the twenty-two participating students to write about their most important lesson, concept, or experience gained from the course, and I used their papers as the basis for a qualitative study of what they had learned from this male positive educational experience. To encourage the students to express themselves freely, I graded this assignment only on whether the work had been satisfactorily completed, not on what was reported: students who adequately completed the assignment were given full credit for it. For the study I grouped their papers into three categories: first, those safe, stock responses that merely reiterated either points made in class or traditional gender-studies commonplaces (five students chose to write those); second, those papers that demonstrated their authors’ ability to undertake a male-positive approach to understanding manhood in both the texts we read and broader socio-historical contexts (thirteen students wrote such papers); and finally, those works that bore witness to their authors’ decision to embrace aspects of a male-positive philosophy, one that celebrates masculinities, critiques their construction, and potentially resists pervasive gynocentric and misandric representations of men (four students’ work provided such evidence). I will only discuss those student responses from the latter two categories because they offer clear evidence that this course successfully enabled more than three-quarters of the students to understand and apply the salient concepts of the course to the literature, its respective contexts, and their lives.

Among the respondents who successfully applied a male-positive approach to the texts and their broader contexts, both women and men commented on the normative gynocentrism they experienced in literature classes. Janey, for example, marvelled that the course enabled her, “to look at gender roles in a different way.” Moreover, she noted that “literature… isn’t all about women,” that after “analyzing women’s roles in literature for the majority of the time [she] has been studying English, it was refreshing to focus on something new.” Mickey similarly noted that “it is refreshing to have the male gender” studied “in a positive light,” that “the texts… read throughout the course… were a refreshing change from the norm.” Both genders also commented on how misandric assumptions pervade our society: Elsie remarked that the course successfully “allowed [her] to see that men shouldn’t always be seen in a negative way as today’s society tells us we should” and roger noted that Kipling’s advocating for stoicism in the face of adversity in “The White Man’s Burden” “stands for the greater burden of all men [commonly and regularly] portrayed in the media.” Women and men, however, differed in their reactions to this misandry: the former were surprised at the profundity of the social pressures and the responsibilities inherent in the manhood question and the latter felt vindicated that their experience was being afforded dignified recognition. Ella appreciated learning about the “the duties and pressures different cultures and time periods put on men”; moreover, she came to appreciate that “men have always displayed tremendous effort to help others besides themselves.” Christine acknowledged the inadequacy of her “stereotypical view of men” to account for the complexity inherent in male-positive criticism: she concluded that as a result of examining “the manhood question, and defining manhood,” she now understood that “a man is very multidimensional.”

Among the male students, Theo remarked on the “enormous pressure on men to live up to [society’s moral] standards”; in addition he appreciated that “respecting these pressures and treating men with dignity” was inherent “in a male-positive approach” to literature. Sam also noted, that “very few people take the time or effort to consider how the men in society are perceived and the pressures that are placed on them”; he was grateful that the course afforded him “a deeper and more cultured understanding of [manhood and masculinity]—something he “thought” he had “figured out.” Sam concluded with satisfaction, “that is all you can really ask for from a class.” These male students clearly felt pleased that the course had respectfully addressed their educational needs. Unique to the men’s responses to the course was an appreciation of both the male-appropriate content of the course—evident in those readings that sought better to understand men’s experiences— and the interest that the course stimulated. after remarking that “there is a lot of pressure put on a man to fit [socially determined, changing roles], Kelvin, for example, discovered that “it’s through literature that we can understand the thoughts and feelings [a] man has [when] he undergoes scrutiny which truly defines [his] manhood and masculinity,” and Adrian concurred that the central issues of the Victorian Manhood Question, “are qualities we [men] still hold onto [and] try and mold ourselves accordingly… because of all of the success” that accompanies them. These men certainly understood that the course encouraged a greater understanding of men’s experience of the social pressures inherent in the manhood question in both the Victorian era and the twenty-first century. Three students praised the male-oriented literature and male-positive approach to it for effectively generating interest in the course topics: Charles remarked that the course “was more interesting to [him] than most literature courses” because it “focused on… masculinity and literature” and this “allowed [him] to learn more because [it] avoided the drollness of most literature course” and “allowed [him] to think more open-mindedly about literature than most courses offered” at the college. roger concurred, praising the course for offering “something more relatable [to him], mak[ing] things much more interesting and keep[ing him] engaged.”

Among the three men who valued the course for being interesting was one who saw similarities between the male-positive aspects of this approach to manhood and his personal struggle with his work ethic and self-confidence. Collin noted that the topic of Victorian manhood “gave the course an interesting twist that made it enjoyable.” He candidly acknowledged: “I have struggled with selfconfidence in all areas of my life,” and in the process of working hard to improve [his] self-confidence, he came to “agree with the Victorian concept that hard work and confidence prove a person’s manhood.” Collin clearly saw the benefits of a male-positive approach to understanding his own experience and was one of four to adopt aspects of its philosophy as his own. Like Collin these students understood that there are similarities between the laudable struggles of Victorian men to attain and sustain manhood and their own twenty-first-century struggles. Nat, for example, noted how lessons learned in the class —and particularly the strong male character in Henley’s “Invictus”— will “allow [him] to be a better man” and “attain manhood.” Two students, however, took their male-positive involvement further: choosing to commit themselves both to adopting a male-positive philosophy in their work and their lives and to critiquing and resisting the misandry they encountered. Ted recognized how the gynocentric nature of his education had caused him to internalize misandric ways of thinking about men. He remarked that misandry, “is similar to the mindset… present in previous courses [he had taken]”; moreover, he felt, “finally to take a class that focused on the elimination of [misandry] was [both a relief] and enlightening.” Ted shared the following reflection: “I was very interested to see how my thoughts about men had been tinted/shaded from past classes, and I was eager to try and eliminate this type of thought process. This aspect of the course educated me on how to look at men and comment on their actions without coloring my thoughts with a bitter tone.”

Alex similarly adopted a male-positive attitude to his educational experience and his extracurricular life, striving for a persistent healthy resistance to the gynocentrism he had encountered in class and at home. “Throughout my life I had never really thought about a male positive approach to anything” Alex remarked; “this class has really taught me to look at stories through multiple lenses because I will always read and analyze stories with a slight male-negative view out of habit, but now I know to stop and look at the same story from a male-positive view in classes and in life.” In sum, alex committed himself to becoming what he succinctly expressed as “a better me based on what I want and not on what others project onto me.” Collin, nat, Ted, and Alex demonstrated through their thoughtful work that carefully accommodating male students in literature courses can have profoundly positive impacts on their lives.

Conclusions

From this teaching experience I offer two interesting observations: first, men of varying levels of academic preparation and commitment to studying literature (reflected in their final course grades) benefitted from a male-positive approach to Victorian literature. The students who either successfully undertook male-positive readings of the texts and their context or chose to adopt a male-positive philosophy represented various levels of academic achievement (their course grades ranged from a though d+). Indeed, those male students who had found the concepts taught in this course sufficiently useful to adopt a male-positive philosophy were men who experienced different levels of academic success in the course. second, only male students were in the latter category of male-positive adopters. no women in the class demonstrated a commitment to future allied behavior. This qualitative study suggests that a male-positive approach to teaching literature —and other courses— could beneficially engage men in exploring their identities through literature and in all aspects of their lives; this approach could also help them build the confidence to demand environments that would succeed academically. doing that would require them to challenge the gynocentric bias they encounter in academic environments. Moreover, adopting a male-positive approach would not disadvantage women students; they performed as well as the men on the assessments in this Victorian Manhood course. although none committed herself to male-positive allied behavior, the women in the class gained a better understanding of men’s identities and an appreciation of the costs and benefits inherent in males’ negotiations of the manhood question.

_______________________

Addendum: The New Male Studies and a Male-Positive Approach to Reading Literature

The new male studies offer an affirmative alternative to traditional gender scholarship on boys and men. Unlike pervasive men’s-studies research, which is fundamentally informed by feminisms, male studies inquiries are essentially male positive: their methodologies not only celebrate men who embody different masculinities, but also critique —and suggests strategies for overcoming— systemic inhibitors of masculine affirmation. Moreover, the precepts informing male-positive methodologies also differ from customary patriarchal assumptions: rather than concerning themselves with what men want for women and for other subordinated men, male studies explore what men want for themselves. The practice of male studies involves acutely attending to how masculinities are inscribed in texts, textual criticism, and pedagogy. In much Western culture, misandric and gynocentric value judgments have profoundly hindered boys’ and men’s wellbeing; for example, reductive chivalric and patriarchal stereotypes; which regard males as little more than pleasers, placaters, providers, protectors, and progenitors; have designated the male body primarily as an instrument of service rather than lauding it as the dignified embodiment of a sentient boy or a man.1 Similar misandric constructions of masculine identities in gynocentric educational environments —particularly those that imagine maleness is in crisis or in need of a cure— have resulted in males experiencing serious education deficits.3

Men are increasingly underrepresented in higher education: Peg Tyre reports that, “[in] 2005,… 57.2 percent of the undergraduates enrolled in american colleges and universities were women,” that “women are [now] better educated” than men, and that “[at] present, 33 percent of women between twenty-five and twenty-nine years of age hold a four-year degree compared to 26 percent of men” (Trouble 32). data from a 2010 report published by the national Center for education statistics (NCES) updates these percentages to thirty-five percent of women and twenty-seven percent of men (aud et al. 214).4 a 2008 american association of University Women report on girls’ performance in education notes that women have earned more bachelor degrees than men since 1982, and that women earned approximately fifty-eight percent of all the bachelor degrees conferred in 2005-2006 (Corbett et al. 55, 62). In 2007-2008, women earned sixty-two percent of associate’s degrees, fifty-seven percent of bachelor’s degrees, sixty-one percent of master’s degrees, and fifty-one percent of doctoral degrees (aud et al. 216). At recent conferences and in the recently launched New Male Studies: An International Journal, scholars have begun to challenge misandric stereotypes and to remedy gynocentric educational biases by applying male-positive methods to textual analysis and teaching practice. I recently designed and taught a course on the Victorian Manhood Question that adopted celebratory and critical male-positive teaching strategies; most students demonstrated that they had understood how misandry and gynocentrism adversely influence not only representations of men and manhood, but also males’ lives; in addition, some even resolved to resist these negative representations whenever they encountered them in literature and in their lives.

Note on this paper

Affiliated with the Modern Language Association of America, the Northeast Modern Language Association (NeMLA) hosts an annual conference primarily for scholars working in the Northeastern United states and Canada. Papers are presented on topics concerning various languages, their literatures, and their pedagogies. In addition, NeMLA supports special-interest caucuses that both investigate certain challenges faced by those working in academe and organize conference panels that address these challenges. among these groups is the Women’s and Gender studies Caucus that, according to its web page, “welcomes members interested in feminist scholarship, women’s and gender studies, and the status of women in the profession at all stages of their careers.” NeMLA does not currently maintain a men’s caucus. Above is one of three papers presented by members of the staff of New Male Studies at the 44th annual NeMLA convention held in Boston, Massachusetts, on March 22, 2013, hosted by Tufts University. The other two papers are included in this issue (see NMS issue below). Each paper offers practical examples of male-friendly strategies that enhance critical inquiry and teaching methods. They comprised a panel, “The new Male studies in Praxis: Male-Positive Criticism and Classroom Practice,” that was initially proposed by one of the presenters (Dennis Gouws) as either a pedagogy or a women’s and gender-studies panel and was accepted as one among nineteen pedagogy panels. Twenty-eight women’s and gender studies panels were accepted.

_______________________

Footnotes

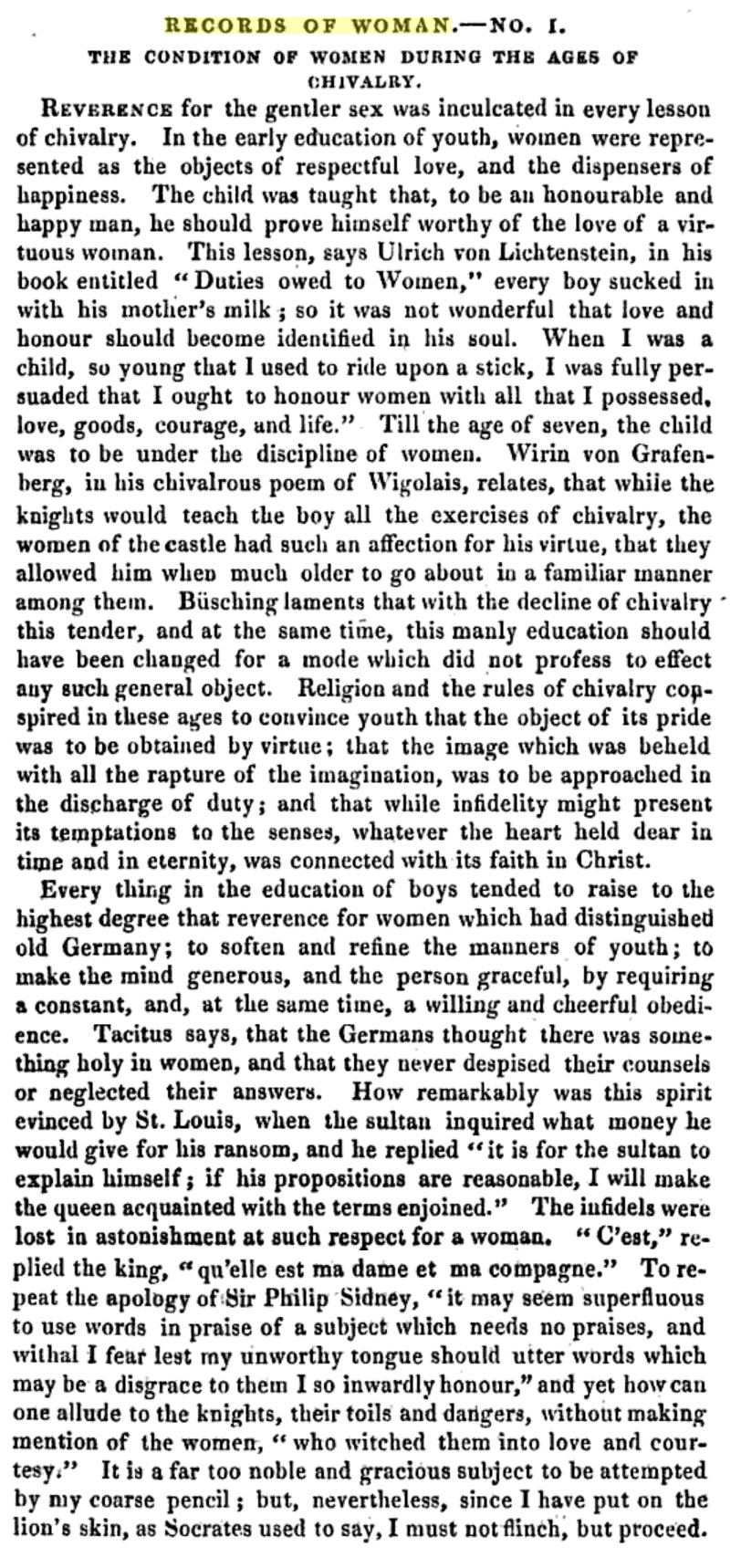

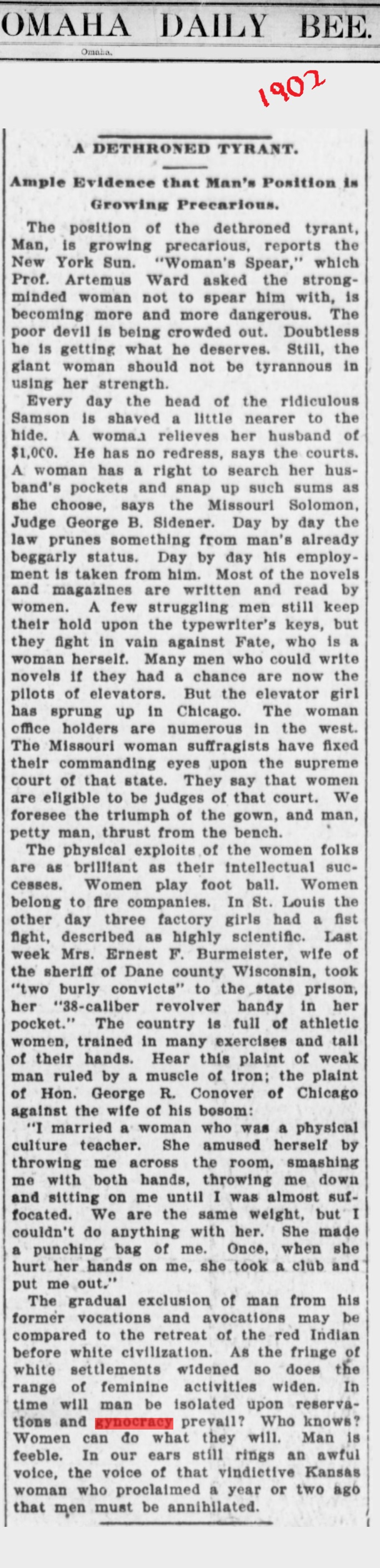

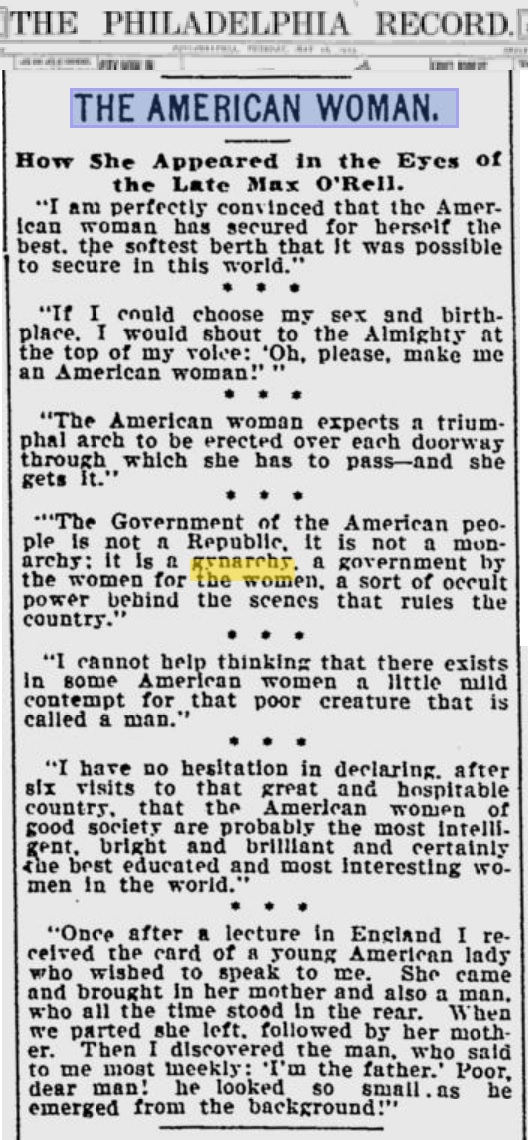

1. Nathanson and Young’s examinations of assumptions about men in western culture persuasively demonstrate how misandry and gynocentrism collude to disadvantage men in popular culture, legal discourse, and contemporary spiritualism. although written more than a decade ago, the first work in the series, Spreading Misandry, effectively models an acute critical attentiveness to negative inscriptions of masculinities in popular culture. In spite of differing on the importance of literary texts to the development of chivalry, nigel saul and Maurice Keen acknowledge the influence of gynocentric values on Chivalry. Keen observes “The conception that chivalry forged of a link between the winning of approbation by honorable acts and the winning of the heart of a beloved woman also proved to be both powerful and enduring; western culture has never since quite shaken itself free of it” (249-50); Warren Farrell explores the contemporary remnants of this conception in his discussion of The Chivalry Factor. The chivalry debate in recent popular essays by emily esfahani smith, Mark Trueblood, and Peter Wright offers vivid testimony of its topicality in the twenty-first century.

2. In addition to Peg Tyre’s work discussed below, see Christina Hoff Summers, chapter seven, “Why Johnny Can’t, Like read.” The updated and revised edition of this book; due to be published in august, 2013; pays more attention to the male-hostile educational environment and offers some suggestions to make the educational experience more boy friendly.

3. Herbert sussman and John Tosh have produced thoughtful, but not necessarily male-positive, scholarship on nineteenth-century British manhood. This field offers many productive opportunities for new male studies research.

References

-Aud, Susan, Hussar, William, Planty, Michael, Snyder, Thomas, Bianco, Kevin, Fox, Mary Ann, Frohlich, Lauren, Kemp, Jana, Drake, Lauren. The Condition of Education 2010 (NCES 2010-028). National Center for education statistics, Institute of education sciences, U.s. department of education. Washington, dC, 2010. Print.

-Corbett, Christianne, Catherine Hall, and andresse st. rose. Where the Girls Are: The Facts about Gender Equity in Education Washington d.C.: aaUW education Foundation, May 2008. Print.

-Esfahani smith, emily. “Let’s Give Chivalry another Chance.” The Atlantic. 10 december 2012. Web. 24 March 2013.

-Farrell, Warren. The Myth of Male Power: Why Men Are the Disposable Sex. new York: Berkley Books, 1994. Print.

-Hoff sommers, Christina. The War Against Boys: How Misguided Feminism Is Harming Our Young Men. new York: Touchstone Books, 2000. Print.

-Keen, Maurice. Chivalry. new Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1984. Print.

-Nathanson, Paul and Katherine K. Young. Spreading Misandry: The Teaching of Contempt for Men in Popular Culture. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2001. 2006. Print.

-Saul, Nigel. Chivalry in Medieval England. Cambridge, Ma, 2011. Print.

-Springfield College Victorian Manhood essays. spring, 2011. Print.

-Sussman, Herbert. Victorian Masculinities: Manhood and Masculine Poetics in Early Victorian Literature and Art. Cambridge and new York: Cambridge University Press, 1995. 2008. Print.

-Tosh, John. A Man’s Place: Masculinity and the Middle-Class Home in Victorian England. new Haven: Yale University Press, 1999. Print.

-Trueblood, Mark. “do you want chivalry or equality? Yes?” A Voice for Men. 10 January 2013.Web. 24 March 2013.

-Tyre, Peg. The Trouble with Boys: A Surprising Report Card on Our Sons, Their Problems at School, and What Parents and Educators Must Do. new York: Crown Publishers, 2008. Print.

-Wright, Peter. “The rise of Chivalric Love: The Power of shame.” A Voice for Men. 30 March 2013. Web. 4 april 2013.

Dennis Gouws is Professor of English at Springfield College and Director of Arts and Education at the Australian Institute of Male Health and Studies. His recent publications include “Orientalism and David Hockney’s Cavafy etchings: Exploring a Male-Positive Imaginative Geography” in The International Journal of the Arts in Society (Vol. 6.6, 2012); and “Boys and Men Reading Shakespeare’s 1 Henry 4: Using Service-Learning Strategies to Accommodate Male Learners and to Disseminate Male-Positive Literacy” in Academic Service-Learning Across Disciplines: Models, Outcomes, and Assessment (2012). Dennis Gouws is Professor of English at Springfield College and Director of Arts and Education at the Australian Institute of Male Health and Studies. His recent publications include “Orientalism and David Hockney’s Cavafy etchings: Exploring a Male-Positive Imaginative Geography” in The International Journal of the Arts in Society (Vol. 6.6, 2012); and “Boys and Men Reading Shakespeare’s 1 Henry 4: Using Service-Learning Strategies to Accommodate Male Learners and to Disseminate Male-Positive Literacy” in Academic Service-Learning Across Disciplines: Models, Outcomes, and Assessment (2012).

|