Stang riding, alternatively referred to as stanging, charivari, or riding the skimmington is a centuries-old practice intended to shame male victims of intimate partner violence by parading them through town on a wooden platform while enduring mockery and ridicule by onlookers. Essentially a vigilante justice action, the practice ceased by the earlier part of last century, or rather has been supplanted by more subtle forms of shaming male victims; ie. telling them to “man up” or by insinuating that a man must have done something wrong to “cause” his female partner to act violently.

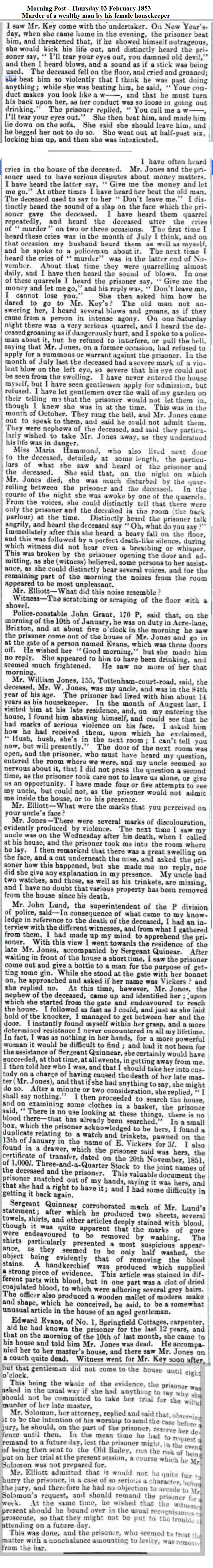

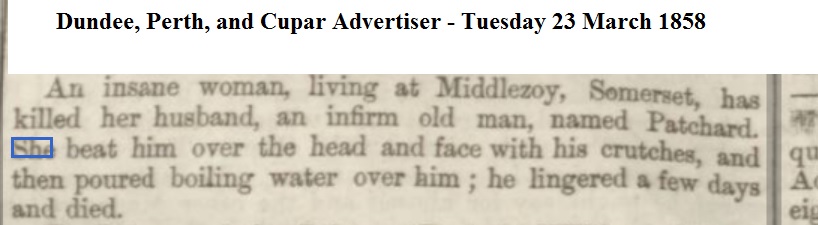

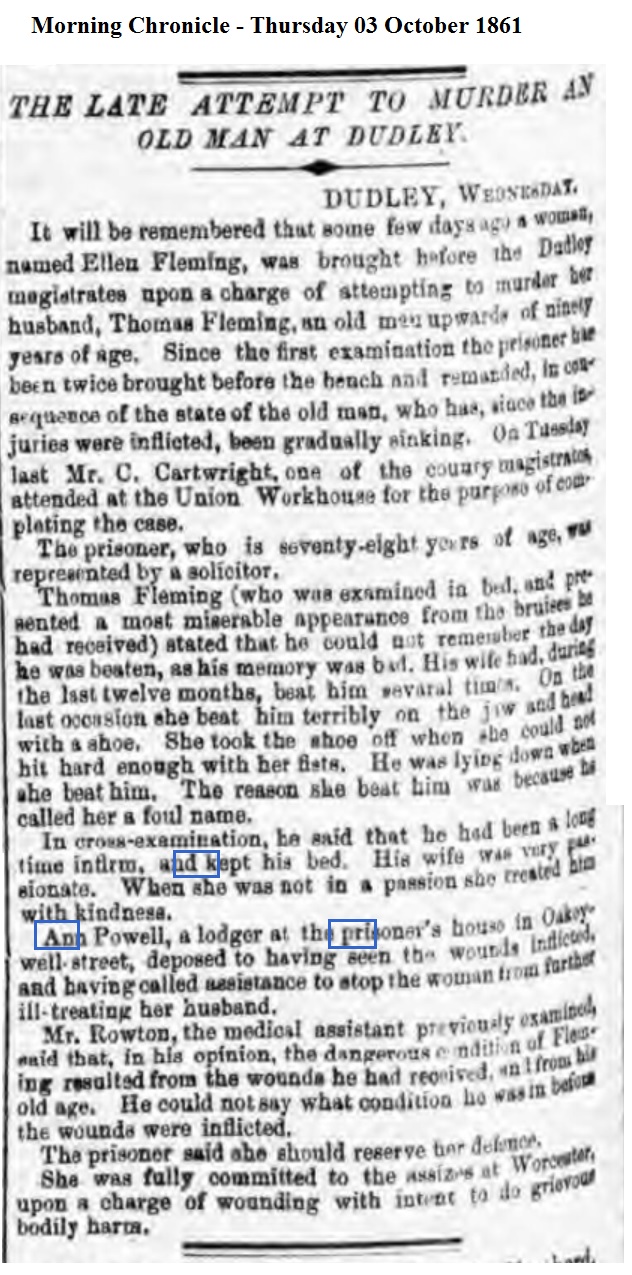

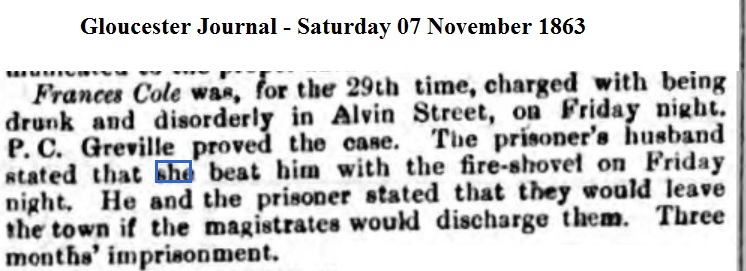

From old newspaper reports in England we get clear evidence of the desire to shame those who rode the stang:

Stang riding – It has been asserted by an old writer that “Shame produceth reformation, where punishment faileth.” 1

“Riding the stang” was one of the few old customs still remaining by which the people of a particular place took the law into their own hands as an assumed right. It was formerly the tendency of the law that for minor offenses the culprits should be punished by some process that appealed to their sense of shame, such as that of the stocks or ducking stool, the pillory and so forth, and “riding the stang” was a popular way of acting on the same principle. 2

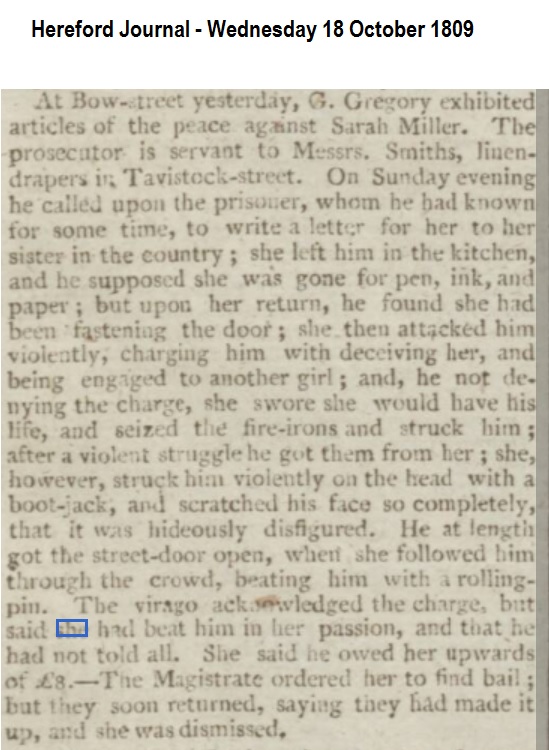

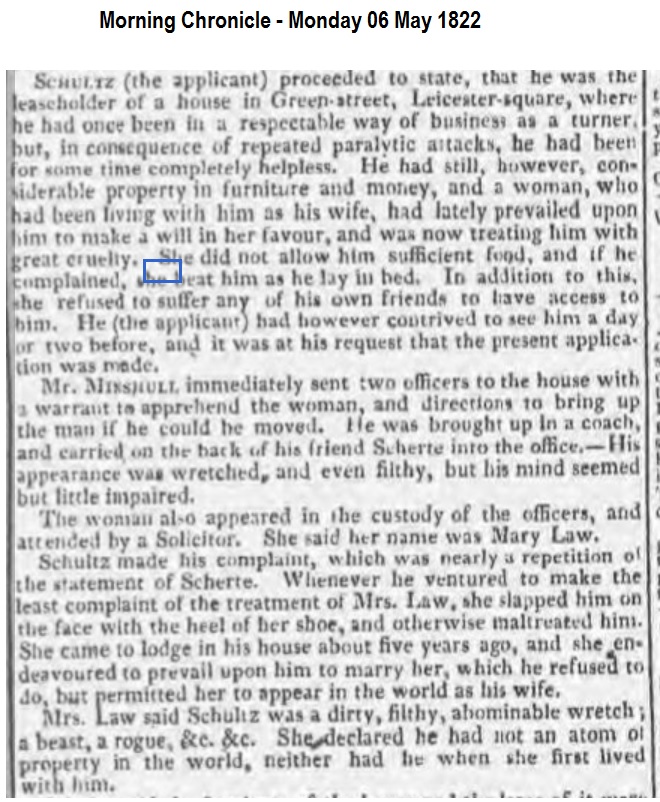

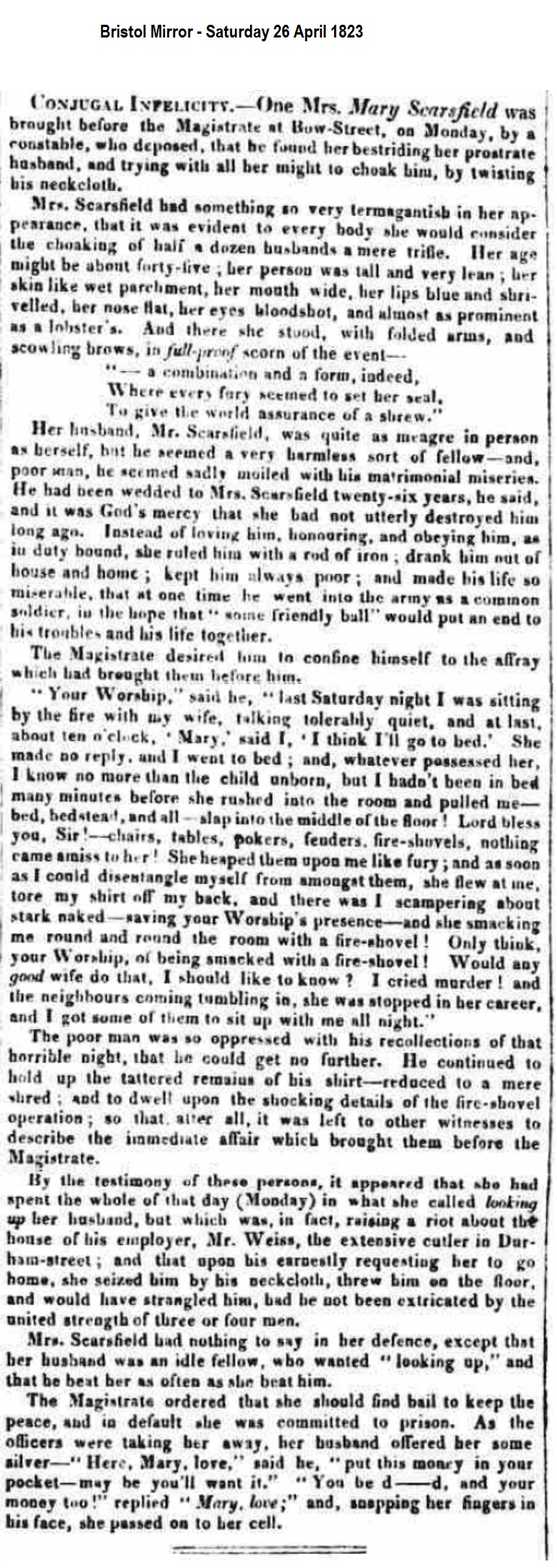

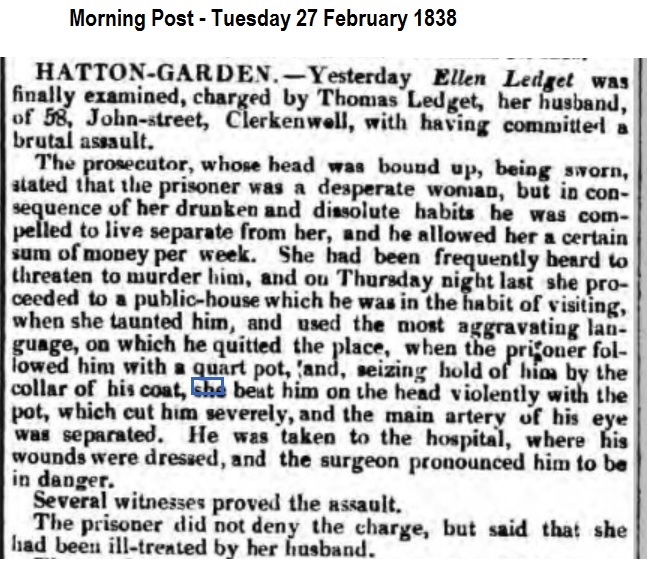

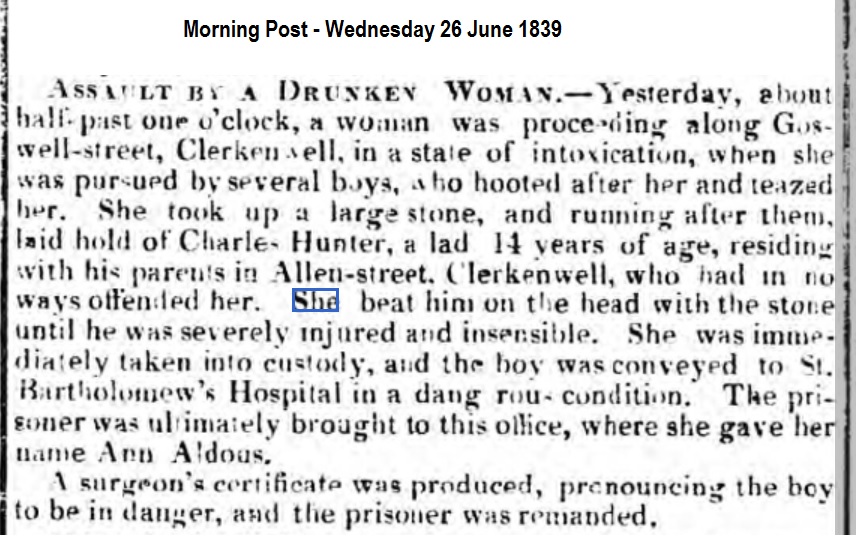

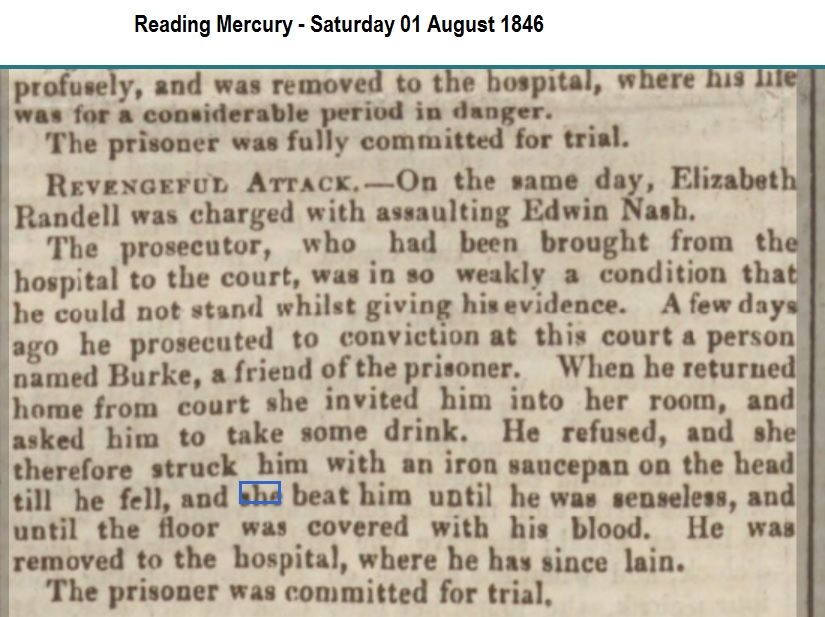

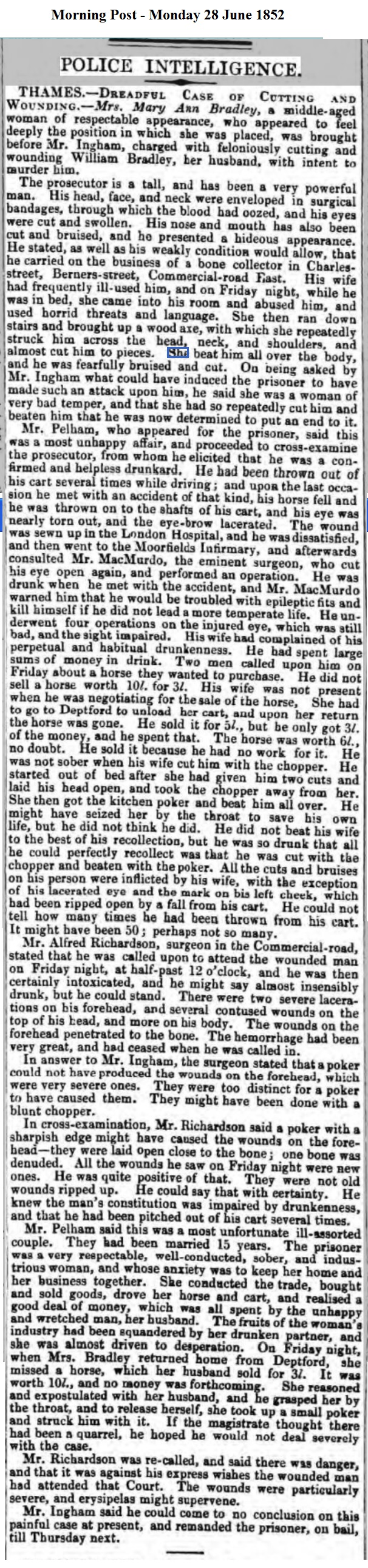

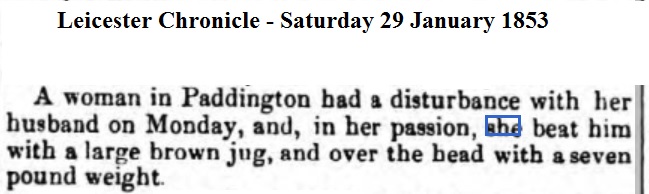

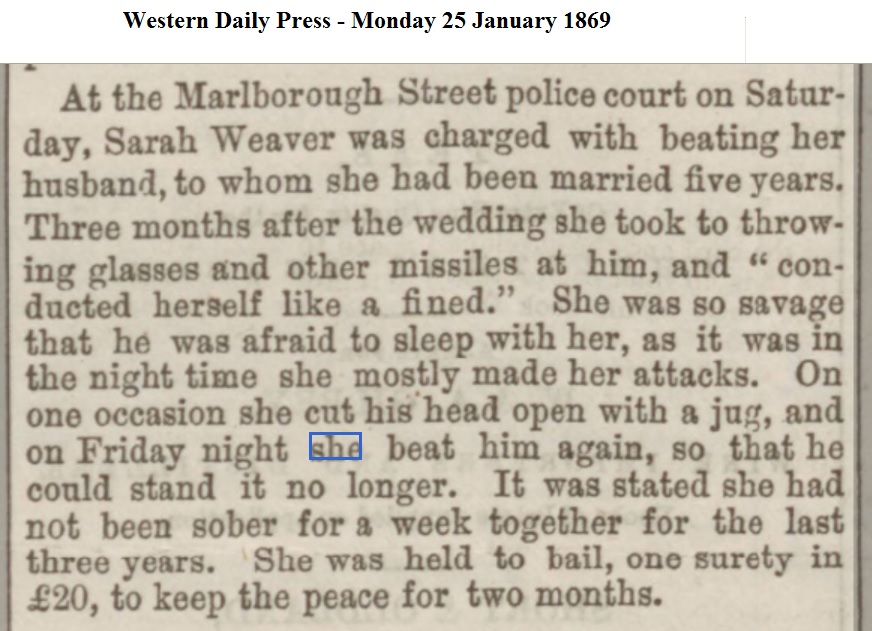

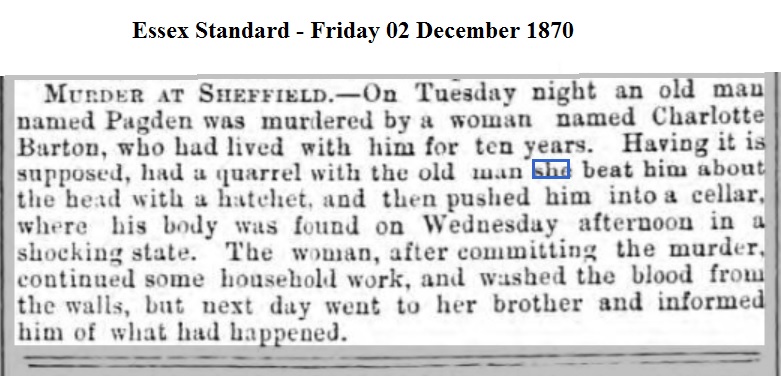

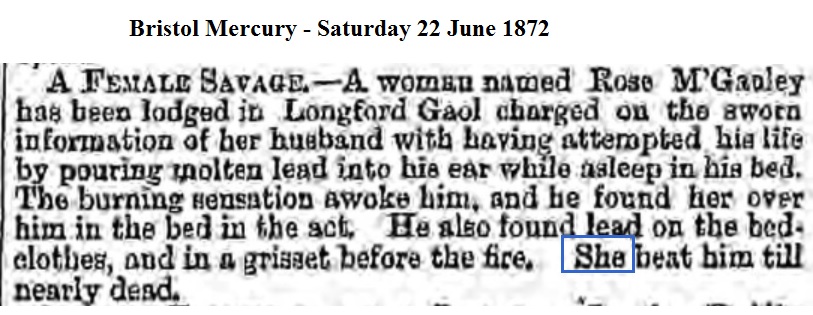

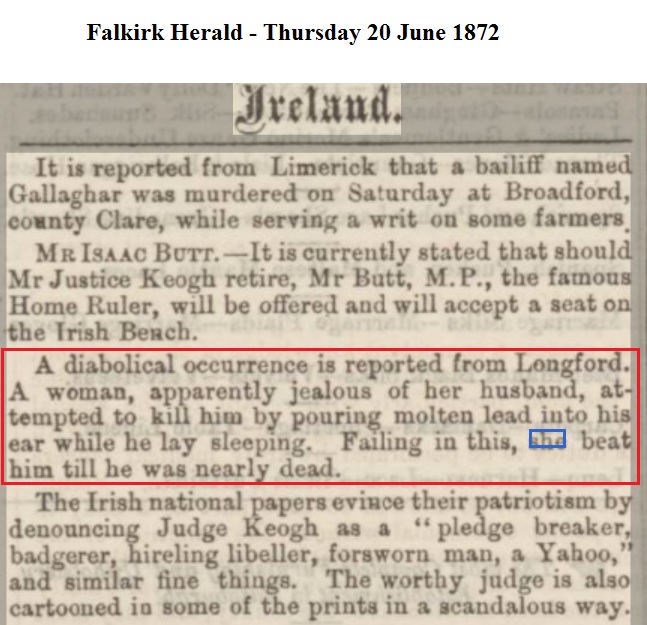

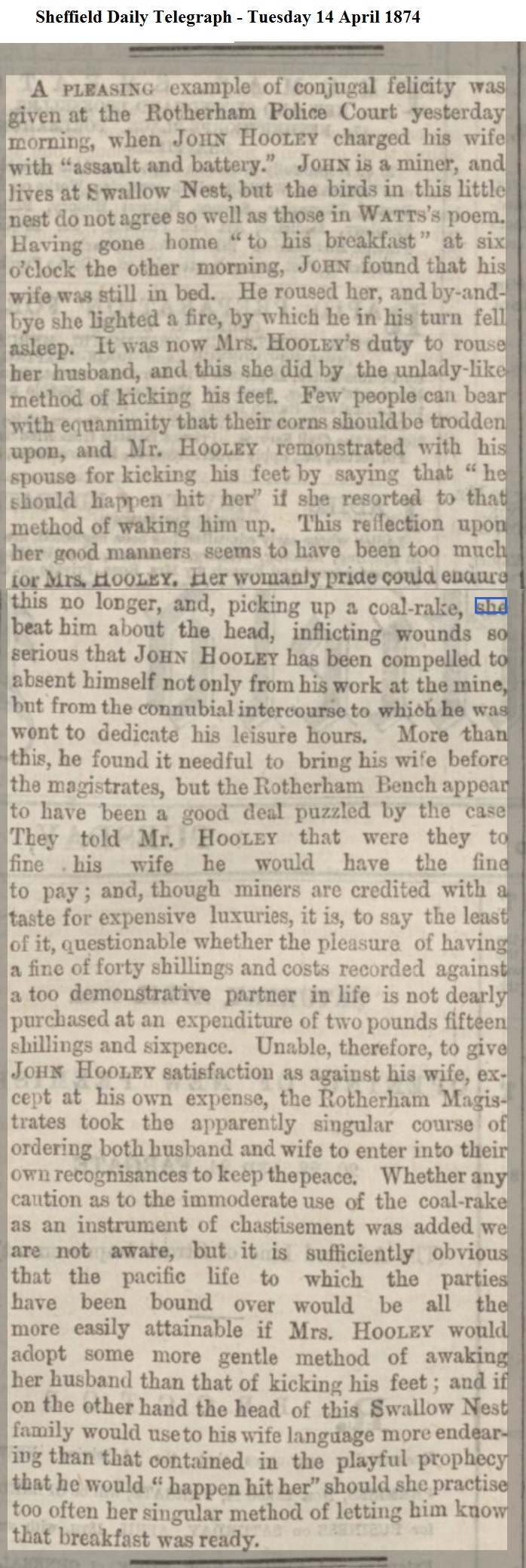

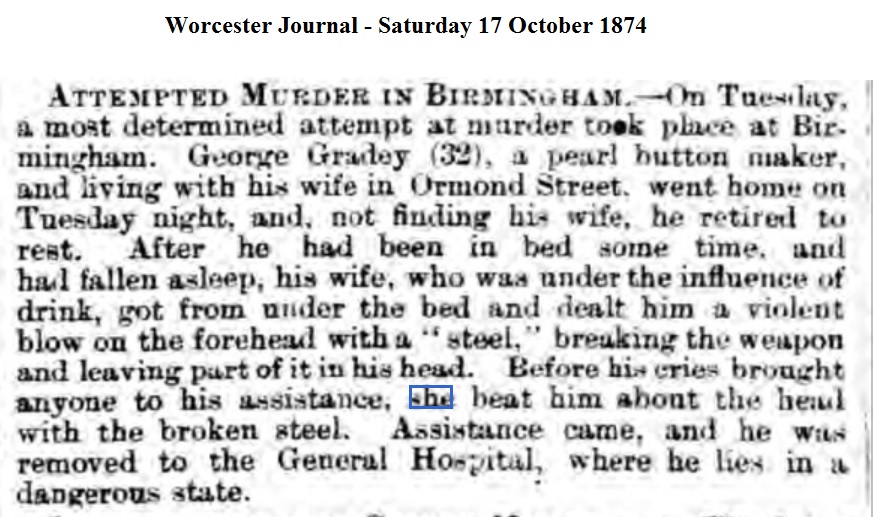

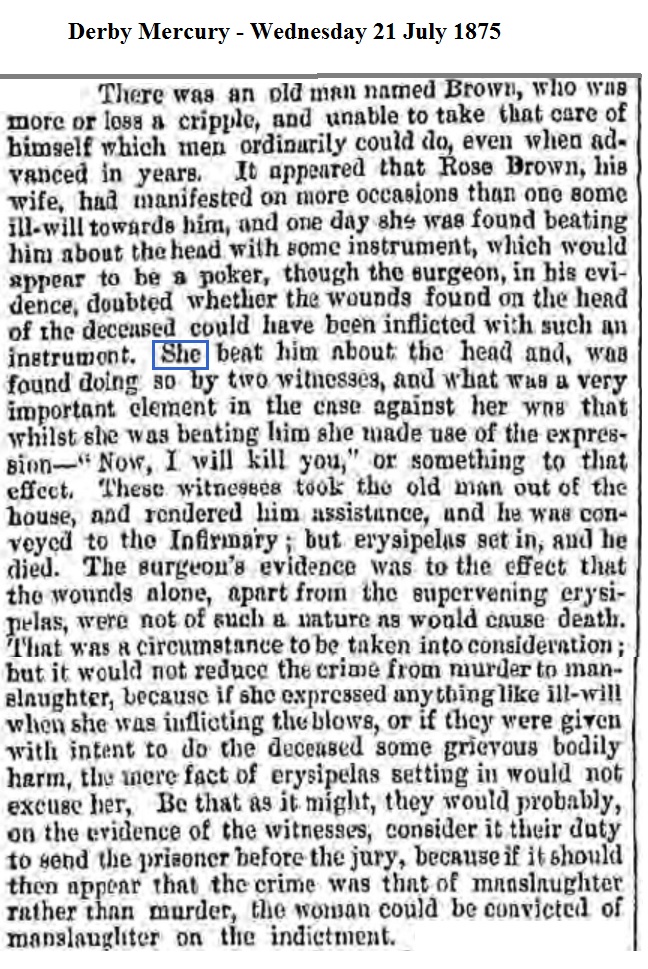

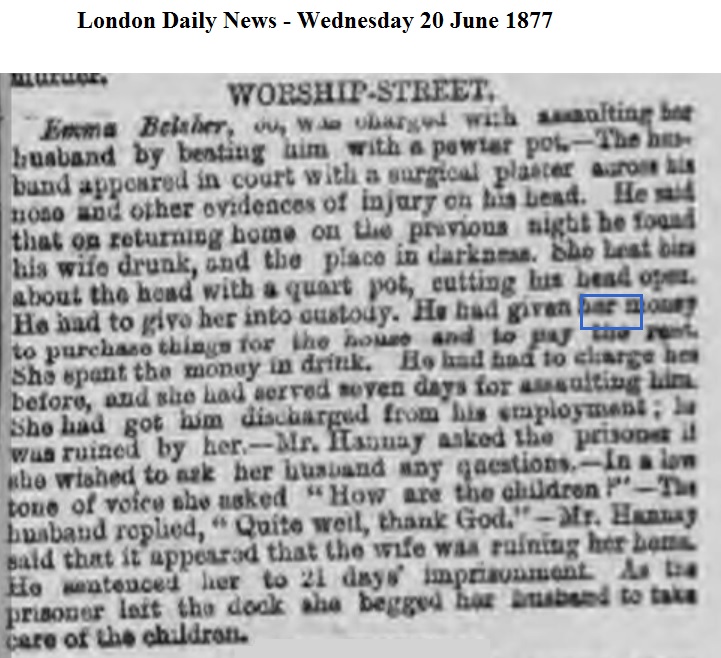

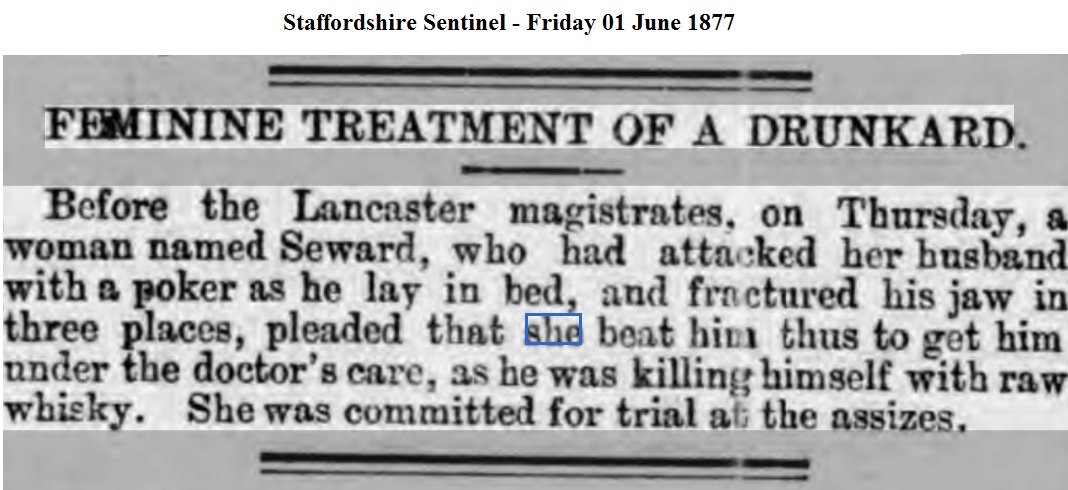

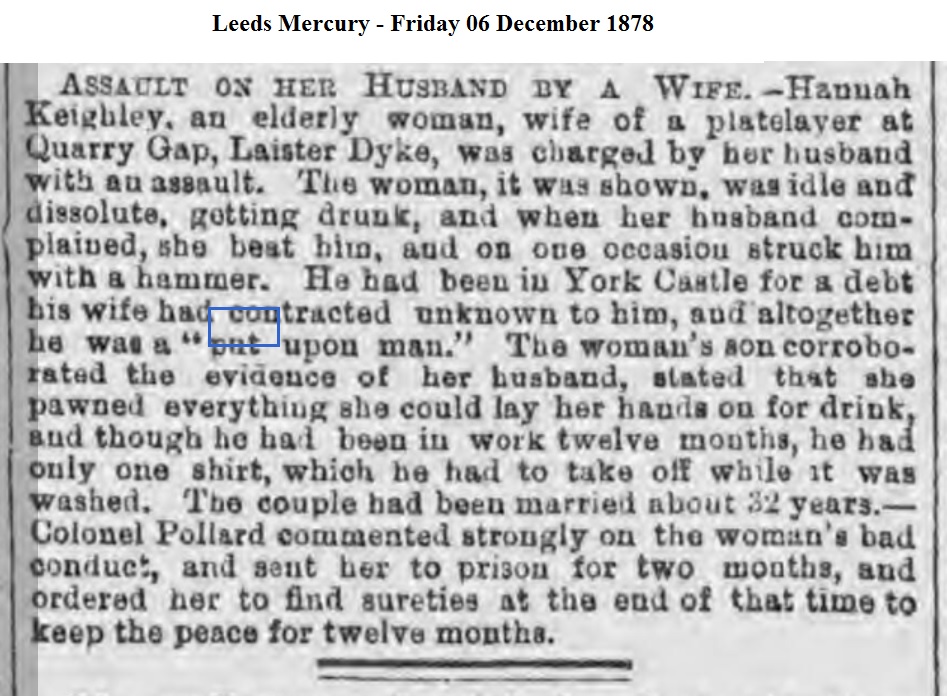

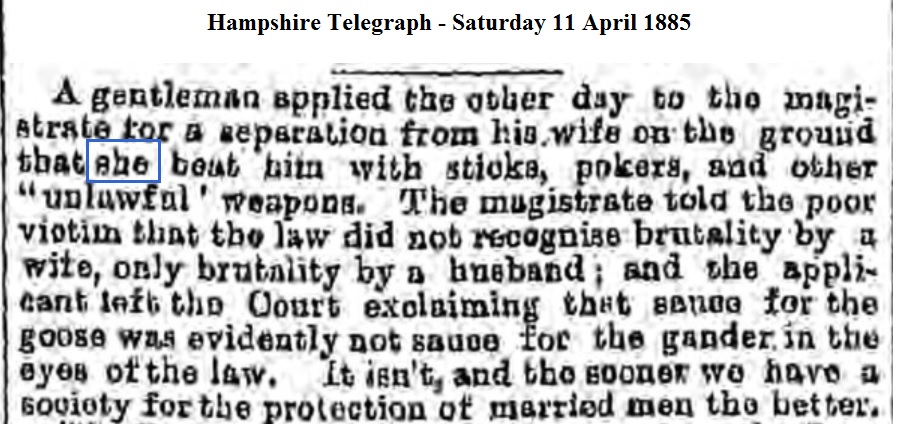

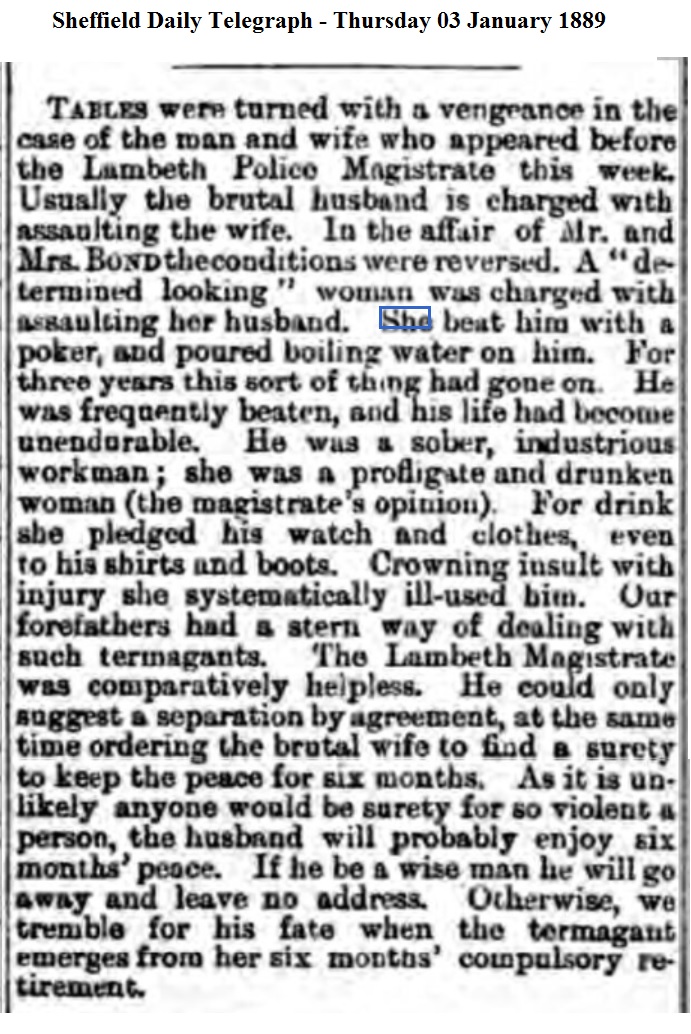

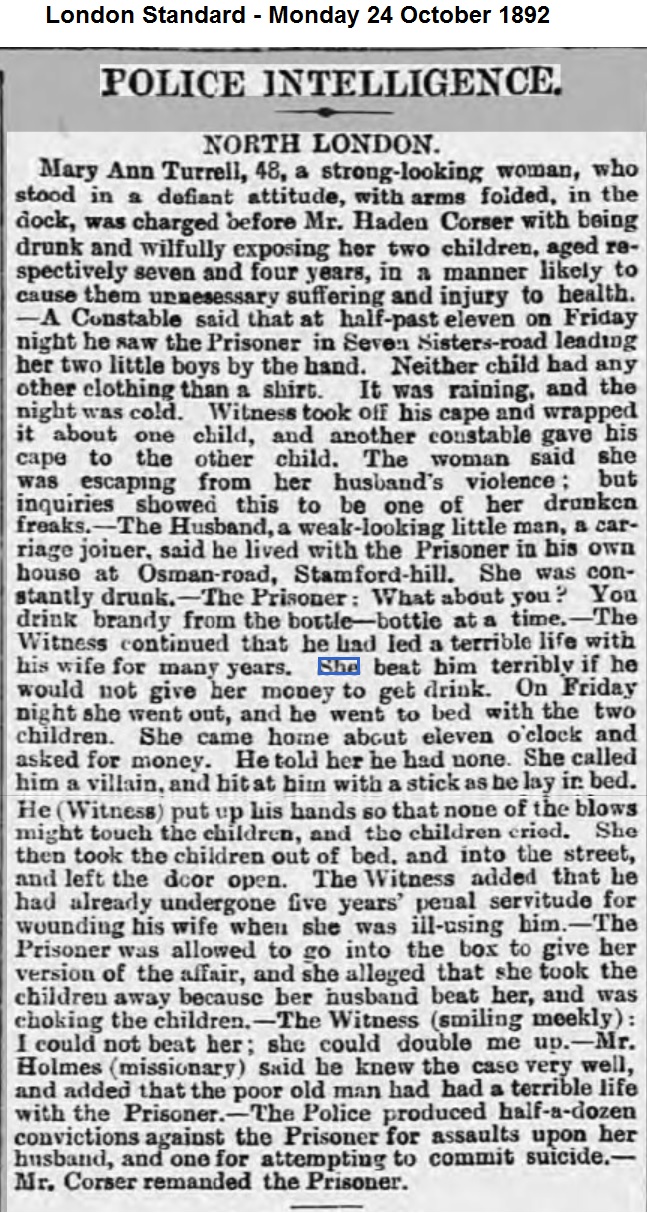

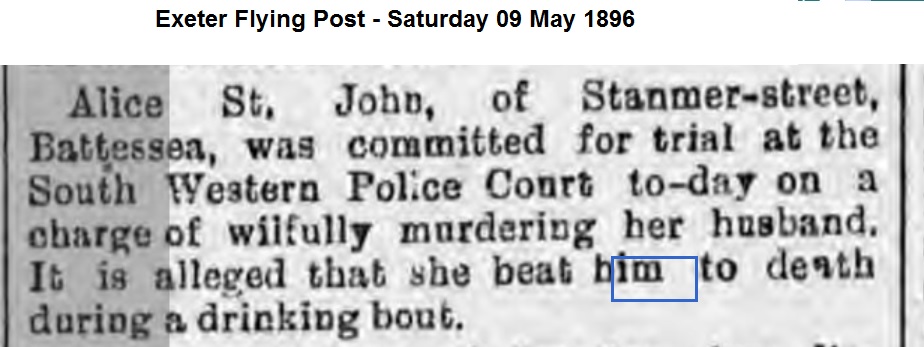

Stang riding was employed for married men and women transgressing social norms, including the norm that a man should defend himself when his wife perpetrated physical violence against him – i.e. If the man failed to defend himself he was forced to ride the stang, as described in the following English newspaper articles from the 1800s:

Stang Riding, or Riding the Skimmington, a mode of punishing certain delinquencies, or of ridiculing a man who allows his wife to beat him, [is] still followed in some parts of the country. It consists of making him ride a wooden horse in procession, with the accompaniment of much noise.3

Stanging, or riding the stang, was a name by which a mode of punishment, at one time very popular, especially in the north of England, was known. It was resorted to in cases where, through the frailty or fault of either party, conjugal felicity had been violated. Sometimes the punishment was occasioned by a rustic swain having allowed his termagant wife to beat him; and this form of the custom has given rise to the slang word “stangey,” ie. a person under petticoat government.4

In several parts of this country there was an old custom… believed to be of Saxon origin, prevailing, which was called Riding Stang. It occurred when a woman was known to have beaten her husband, and the mode of procedure was as follows:- the neighbours being assembled together, two men get into a cart and are drawn about by other men, when they beat an old tin can with a stick, a number of nonsensical lines are repeated, and the assembled multitude shout; and all this must be done in four neighbouring townships before the Stang Riding can be completed. Two men of the names Bent and Muddyman sometime ago came to reside at Hyde from a Stang Riding district, where they had not long been, before Bent got married, and Muddyman promised that when he [ie. Bent] allowed his wife to thrash him, he would give him the benefit of a Stang Ride. It was not long before Muddyman’s anticipations that Bent’s wife would thrash him were realized, and not forgetting his promise, a muster was made, and the ceremony was commenced on the evening of the 27th of July, when the plaintiff and Muddyman got into a cart, with a stick and a saucepan, with which they contrived to make some music, and the plaintiff repeated the following lines:-

Ran, dan, dan,

This you mun know by the sound of our can,

One of our neighbours has beat her good man;

Not for eating or drinking or feeding on souse,

But for spending two-pence in a neighbour’s house;

If he’ll be a good fellow and do so no more,

We won’t never sound our can at no neighbour’s door.Muddyman, who was in the cart, and held one of the musical instruments, then made the following beautiful response:-

Tink of a kettle—tank of a pan,

This brassy-faced woman has beaten her man,

Neither with sword, dagger or knife,

But with an old shuttle she’d like to have taken his life.The can was then again tinkled, and the shout having been set up, the cart was drawn to the townships of Godley and Haughton, the crowd accompanying it, where the same ceremony was performed, and the cavalcade returned in perfectly good order, through Hyde, toward another township, it being necessary that they should visit four.5

The stang is of Saxon origin, and is practiced in Lancashire, Cumberland, and Westmoreland, for the purpose of exposing a kind of gynocracy, or, the wife wearing the gallskins. When it is known (which it generally is) that the wife falls out with her spouse, and beats him right well, the people of the town or village produce a ladder, and instantly repair to his house, where one of the partly is powdered with flour–face blackened–cocked hat placed upon his cranium–white sheet thrown over his shoulders–is seated astride the ladder–with his back where his face should be–they hoist him upon men’s shoulders–and in his hands he carries and long brush, tongs, and poker. A sort of mock proclamation is then made in doggerel verse at the door of all the ale-houses in the parish, or wapentake, as follows:

It is neither for your sake nor my sake

That I ride the stang;

But it is for Nancy Thomson,

Who did her husband hang.

But if I hear tell that she doth rebel,

Or him complain, with fife and drum

Then we will come,

And ride the stang again.

With a ran tan tang,

And a ran tan tan tang,” &c.6

Notice the man in the latter example is forced to carry a “long brush, tongs, and poker,” household objects usually attended by women, perhaps as an attempt to feminize and portray him as unmanly. One is reminded here of the centuries old Henpecked Club which held annual street processions of battered men carrying women’s household utensils, which symbolized their humility and humiliation.

Stanging as a method of shaming abused men took many forms, differing from town to town and from incident to incident. However one thing these rituals had in common was the attempt to shame male victims of domestic violence. While this history is readily available in newspaper and other archives, today’s historians of sociology have avoided any publishing or commentary on the material, hence this article to raise awareness of what we might aptly refer to as his-tory.

Sources:

[1] Chester Chronicle – Friday 28 May, 1813

[2] Cork Examiner – Monday 28 August, 1865

[3] Salisbury and Winchester Journal – Saturday 27 September, 1856

[4] Kent and Sussex Courier – Friday 13 August, 1880

[5] Chester Chronicle – Friday 27 April, 1827

[6] Lancashire Mirror – 18 January, 1829

You must be logged in to post a comment.