Many social media commentators discuss the rise of hypergamous behaviors among modern women. Some pose reasonable evolutionary hypotheses for such behavior, but there may be another cause at work – cultural narcissism.

Observations of extreme hypergamy among women may be equally explained by the rise of cultural narcissism in affluent societies (Twenge & Campbell, 2009), a motive that differs from baseline hypergamy, but which nevertheless involves comparable behaviors of self-enhancement and status-seeking.

Society’s encouragement of men in chivalric deference to women, and the associated practice of ‘placing women on a pedestal’, has generated a degree of gendered narcissism among women over time. To frame this differently, Acquired Situational Narcissism can arise with any acquired social status; for example in academic experts, politicians, pop singers, actors – and also in women who, in modern society, are taught that they deserve to be recognised for thier worth, dignity, value, purity, status, reputation and esteem in the context of their relationships with men. This psychological disposition in women, partly a result of traditional chivalry, promotes exaggerated self-enhancement behaviours beyond what evolutionary models of hypergamy would require.

Among narcissistic individuals, studies find higher incidence of hypergamy-like behaviors, indicating that such behavior is not the result of a culture of sexual liberation alone, nor of baseline evolutionary imperatives; it may also be the result of an acquired social class narcissism that says “I deserve.”

Excerpts from narcissism studies:

A third strand of evidence concerns narcissists’ relationship choices. Because humans are a social species, relationship choices are an important feature of situation selection. Narcissists are more likely to choose relationships that elevate their status over relationships that cultivate affiliation. For example, narcissists are keener on gaining new partners than on establishing close relationships with existing ones (Wurst et al., 2017). They often demonstrate an increased preference for high-status friends (Jonason & Schmitt, 2012) and trophy partners (Campbell, 1999), perhaps because they can bask in the reflected glory of these people. In sum, narcissists are more likely to select social environments that allow them to display their performances publicly, ideally in competition with others. These settings are potentially more accepting and reinforcing of narcissistic status strivings.

Source: The “Why” and “How” of Narcissism: A Process Model of Narcissistic Status Pursuit1

Consistent with the self-orientation model, Study 5 provided an empirical demonstration of the mediational role of self enhancement in narcissists’ preference for perfect rather than caring romantic partners. Furthermore, these potential romantic partners were more likely to be seen as a source of self-esteem to the extent that they provided the narcissist with a sense of popularity and importance (i.e., social status). Narcissists’ preference for romantic partners reflects a strategy for interpersonal self-esteem regulation. Narcissists also were attracted to self-oriented romantic partners to the extent that these others were viewed as similar. The mediational roles of self-enhancement and similarity were independent. That is, narcissists’ romantic preferences were driven both by a desire to gain self-esteem and a desire to associate with similar others.

Narcissism has been linked with the materialistic pursuit of wealth and symbols that convey high status (Kasser, 2002; Rose, 2007). This quest for status extends to relationship partners. Narcissists seek romantic partners who offer self- enhancement value either as sources of fawning admiration, or as human trophies (e.g., by possessing impressive wealth or exceptional physical beauty) (Campbell, 1999; Tanchotsrinon, Maneesri, & Campbell, 2007)

Source: The Handbook of Narcissism And Narcissistic Personality Disorders3

Narcissists are looking for partners who can provide them with self-esteem and status. How can a romantic partner provide status and esteem? First, he or she can do so directly: a romantic partner who admires me and thinks that I am wonderful elevates my esteem. Second, he or she can do so indirectly through a basic association: my partner is beautiful and popular, therefore I am too. This indirect esteem generation is clear from a range of social psychological research, from the self-evaluation maintenance (SEM) model (Tesser, 1988) to Basking in Reflected Glory (BIRGing; Cialdini et al., 1976). This indirect esteem provisioning is evident in the term “trophy” partner.

There is good empirical evidence that narcissists like targets who provide esteem and status both directly and indirectly (Campbell, 1999). There is also an important interaction effect. Namely, narcissists like popular and attractive partners, especially when those others admire them. Narcissists, however, are not particularly interested in admiration from just anybody. This finding is inconsistent with the “doormat hypothesis.” Narcissists are not looking for someone they can walk on and who worships them; rather, narcissists are looking for someone ideal who also admires them.

The next question, of course, is what characteristics of a potential partner make them able to provide narcissists with narcissistic esteem? Not surprisingly, what narcissists particularly look for in a partner are physical attractiveness and agentic traits (e.g., status and success). A narcissist’s ideal partner is like a narcissist’s ideal self (recall Freud’s comments): attractive, successful, and admiring of the narcissist. Indeed, in our research, narcissists report that part of the reason that they are drawn to attractive and successful partners is that these people are similar to them (Campbell, 1999).

Dozens more quotations could be added, however the point is obvious: self-enhancement strategies of both narcissism and hypergamy share overlapping features.

The rise of narcissistic behaviors among women is receiving increased attention from academia, particularly with the addition of new variants to the lexicon such as communal narcissism, and vulnerable narcissism, which appear to be preferred female modes of expressing narcissism. A more in-depth survey of narcissism variants among women, and their implications can be read here.

Hypergamy, as an evolutionary motivation, doesn’t require a woman to overestimate her own attractiveness and desirability as she seeks to secure high resource/status males. Narcissism, on the contrary, does entail an overestimation by women of their own attractiveness & desirability as they seek to secure high resource/status males.

To discover whether hypergamy or narcissism is at play, one might simply ask a woman to rate her own attractiveness. If she strongly overrates herself, then her mating-up is likely driven by narcissism and is maladaptive. If she rates herself honestly, then her desire to mate up is more likely driven by an adaptive hypergamy. Mating-up today appears largely driven by maladaptive narcissism; therefore any rationalizing or excusing it as “natural” and “adaptive” serves to compound and increase that same culturally-driven narcissism.

A note on terminology:

Sigmund Freud introduced narcissism as a developmental trait that ranged from healthy to unhealthy.5,6 Some evolutionary psychologists posit that a degree of narcissism might be adaptive in the wider evolutionary sense, though this hypothesis (which has zero genetic evidence to confirm it) can only be applied to a limited subset of behaviours before tipping into maladaptive expressions of narcissism as measured by the usual psychometric instruments.7,8,9 Moreover, no one has satisfactorily demonstrated that a mild, non-pathological narcissism is adaptive and belongs to a construct continuum with more pathological narcissism; therefore it is conjecture to claim that narcissism is natural, but that it simply “gets out of hand” at the more extreme end of a hypothesised spectrum.

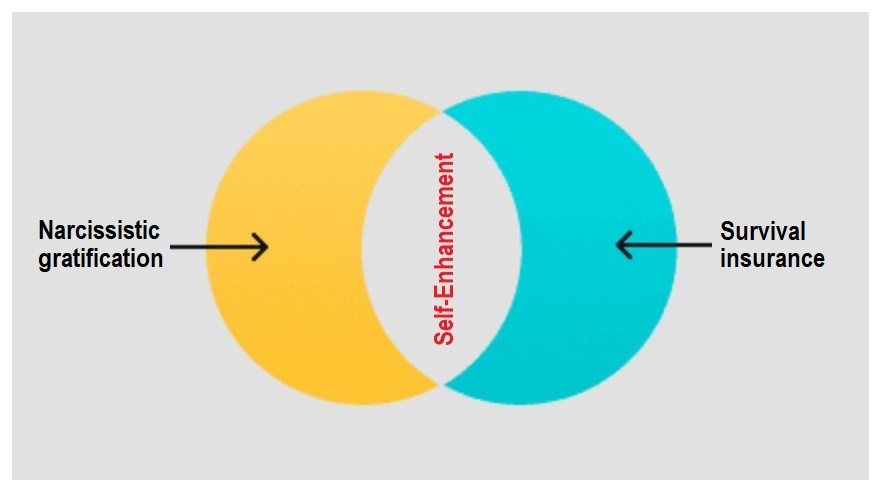

With these points in mind it’s necessary to differentiate between female self-enhancement as an evolutionary survival strategy, versus female self-enhancement as a maladaptive, narcissistic pathology. The narcissistic self-enhancement we see increasingly demonstrated among women today is not a contributor to evolutionary success; on the contrary it works to undermine family ties, corrode intimate relationships, and is also associated with lowering the birth rate – the exact opposites of conditions required for “adaptive.” Lastly, by differentiating hypergamous self-enhancement from narcissistic self-enhancement we avoid the error of encouraging or excusing narcissism under the banner of it being “natural.”

Maladaptive vs. adaptive versions of self-enhancement

REFERENCES:

[1] Grapsas, S., Brummelman, E., Back, M. D., & Denissen, J. J. (2020). The “why” and “how” of narcissism: A process model of narcissistic status pursuit. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(1), 150-172.

[2] Campbell, W. K. (1999). Narcissism and romantic attraction. Journal of Personality and social Psychology, 77(6), 1254.

[3] Wallace, H. M. (2011). Narcissistic self-enhancement. The handbook of narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder: Theoretical approaches, empirical findings, and treatments, 309-318.

[4] Campbell, W. K., Brunell, A. B., & Finkel, E. J. (2006). Narcissism, Interpersonal Self-Regulation, and Romantic Relationships: An Agency Model Approach.

[5] Freud, S. (2014). On narcissism: An introduction. Read Books Ltd.

[6] Segal, H., & Bell, D. (2018). The theory of narcissism in the work of Freud and Klein. In Freud’s On Narcissism (pp. 149-174). Routledge.

[7] Holtzman, N. S., & Donnellan, M. B. (2015). The roots of Narcissus: Old and new models of the evolution of narcissism. Evolutionary perspectives on social psychology, 479-489.

[8] Holtzman, N. S. (2018). Did narcissism evolve?. Handbook of Trait Narcissism: Key Advances, Research Methods, and Controversies, 173-181.

[9] Czarna, AZ, Wróbel, M., Folger, LF, Holtzman, NS, Raley, JR, & Foster, JD (2022). Narcissism and Narcissistic Personality Disorder: Evolutionary roots and emotional profiles. In TK Shackelford & L. Al-Shawaf (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Evolution and the Emotions. Oxford University Press.