Throughout history we witness the continuing fight between powers of order and those of chaos, a battle that takes place on the cultural scene, and within our own psyche.

Understood via the language of mythology, both monotheism (singular order) and polytheism (multiple order) provide protections against chaos, although the monotheistic mindset might argue that polytheism is itself a form of chaos; a charge that falls flat on further investigation.

The polytheism showcased in traditional mythologies, with its participatory democracy among the gods, provides a helpful restraint against chaos via the following routes:

- Individual gods & their cults apply restraint against over-reach by other gods and their cults.

- The Olympian pantheon is governed by the principle of inclusive democracy.

- Tragedy, as portrayed in polytheistic mythology, serves as a warning against disintegrative practices of hubris, narcissism and lawlessness.

- Representation of Titans as forces of unstructured (and deconstructing) excess are actively suppressed by ordered Olympian society.

Polytheism can thus be understood as a framework embracing a plurality of value systems, social customs, and political structures: in a word, order. In this sense it works as a foil against chaos.

In his excellent book The New Polytheism (1974), David Miller contrasts polytheism’s ‘many centres of order’ with the alternative of chaos:

Polytheism is the name given to a specific religious situation. The situation is characterized by plurality, a plurality that manifests itself in many forms. Socially, polytheism is a situation in which there are various values, patterns of social organization, and principles by which man governs his political life. These values, patterns and principles sometimes mesh harmoniously, but more often they war with one another to be elevated as the single center of normal social order. Such a situation would be sheer anarchy and chaos were it not possible to identify the many orders as each containing a coherence of its own. [Miller, 1974]1

To Miller’s observation about intra-warring tendencies within polytheism I would also add that the monotheistic mindset engages in a comparable extra-warring tendency toward individuals and societies possessing contrary religious values or gods, thus rendering moot any distinction between monotheism and polytheism when it comes to a war reflex targeting the proverbial ‘other.’ The basis of polytheistic theology, however, is an inbuilt assumption that a variety of gods and their imperatives belong within the overall pantheon – whereas monotheism is more often “jealous” about the right to hold exclusive power.

The chaos that both monotheism and polytheism negate was personified in Greek mythology by the Titans, and I will be using the rest of this article to explore the nature of these mysterious and destructive figures.

The Titans were never well defined, certainly not with the sharp borders and contours typical of the Olympians with their respective domains of interest; so on that basis the Titans fall short of the clear structuralism we reserve for archetypes. We could perhaps stretch the notion of archetypes into a rubbery shape, as did one author who proposed it is possible to view Titanism as the “archetype of excess,” but this clear definition belies their shapeshifting, amorphous and ultimately form-destroying natures.

Much confusion has arisen within Jungian circles as to what constitutes an archetype. While excessiveness or destructiveness are certainly part of our human repertoire, they fall short of what we might call complex personality structures, acting instead as singular impulses, functions, or instincts.

The question Jungians often ask is- should we refer to simplistic human functions as ‘archetypal’ in nature, or reserve this designation for more complex configurations? The Greeks for example tended to personify complex figures such as Aphrodite and Apollo, which are reasonably referred to as archetypal patterns. But the Greeks also personified simplistic functions such as Phobos (fear), Phthonos (envy), Nemesis (revenge), Oizys (misery), Limos (hunger) etc. which lacked the complexity of the Olympian archetypes. For this article, then, we will stick with the practice of naming simple impulses or instincts (such as titanic destructiveness) as functions, and reserve the word archetypal for the more elaborate configurations.

Chaos and the Titans

The very first association of the Titans with Chaos comes from Hesiod’s Theogony (700 BC) where he tells that after being defeated by the Olympian order, the Titans dwelt beyond the threshold of Chaos:

“There lies the sources and the limits

of black earth and of mist-wrapped Tartaros,

of the barren sea, too, and of the starry sky,

and they are grim and dank and loathed even by the gods.There stand the gates of marble and the threshold of bronze,

unshakable and self-grown from the roots that reach

deep into the ground. In front of these gates, away from all the gods

dwell the Titans, on the other side of murky Chaos.“2

As Hesiod tells here, the Titans dwell in murky chaos far away from the Olympian gods, suggesting that these two forces cannot mix to form a harmonious synthesis.

Jungian author Rafael Lopez-Pedraza provides a further analysis from an archetypalist point of view, detailing specific features of Titanism in the following survey:

“Kerenyi gives us a general picture of the psychology of the Titans: no laws, no order, no limits.

For didactic purposes, we can say that, just as the Greeks thought of the Titanic times as the reign in earlier times of more savage celestial Gods, in the ontogenesis of man, there have also been Titanic times. Our own adolescence probably contains a large element of Titanism — excess, unboundedness, lawlessness, chaos, barbarism and so on…

Let us push this Titanic element even further. Kerenyi’s view of the Titans, that they represent a particular function, is perhaps what I am trying to get at concerning this Titanic ingredient which exists in us all. However, we are faced here with a difficulty; a function suggests something specific, whereas Titanism seems so disparate and wild…

I have already mentioned the well-defined Gods and Goddesses with their consistent images; in other words, the archetypes. Nilsson again: “Anthropomorphism has, therefore, a characteristic limitation.” If that is so, it is difficult to see the Titans (whose main characteristic is excess) as archetypes with their own inherent limitation, and even more difficult to see them as the images of an archetype. Furthermore, Nilsson states: “The Titans are abstractions or empty names of whose significance we cannot judge.” So to call the Titans archetypes, or even representatives of a particular function, is a bit risky. If we were to follow Kerenyi on this point and agree that the Titans represent a particular function, then the Titans, with their excessiveness, could be called the archetype of excess.

Nevertheless, in poetry and iconography the Titans are personified, represented as forms, enabling us, perhaps, to broaden our view of anthropomorphism and imagine the forms of the Titans as a sort of borderline anthropomorphism. Personally, I prefer to view them as mythological figures representing mimicry and excess, for they are not archetypal configurations. In order to gain insight into this mimetism, jargon and excess, we need a strong archetypal training and point of view; it is only by having those well-defined forms as a background that we can have insight into what is, by definition, formless in human nature…

We have the literature running from Camus’ The Outsider, published during the war (in 1942), to Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange, to confirm this impression. I connect what Camus and Burgess expressed in their novels, in terms of mythology and Archetypal Psychology, with the Titanic level in man which we have been tracking: no laws, no order, no limits — in short, excess. Once again, it is literature which has opened the door to an exploration (which we in psychology are just beginning) of those levels in man where the Titan lurks. But, following Kerenyi again, we have to accept that, in the history of human life, the Titanic expresses itself where we are excessive. In this sense, the Titanic could be, if not an archetype, then a particular function.” 3

Note his many descriptions of the Titans – no laws, no order, no limits, formless, excess, savage, unboundedness, lawlessness, chaos, barbarism, disparate and wild, (etc.) – descriptions which we will use, along with other features, to construct a final picture of Titanism below.

The next description of the Titans comes from James Hillman’s article titled And Huge Is Ugly: Zeus and the Titans,4 where he singles out the presence of destructive excess:

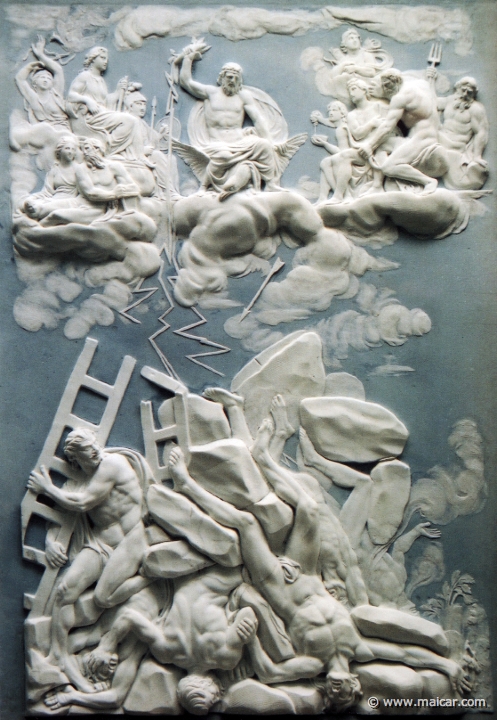

“A sign of the absence of the gods is hugeness, not merely the reign of quantity, but enormity as a quality, a horrendous or fascinating description, like Black Hole, Conglomerate, Megapolis, Trillions, Gigabytes, Star Wars. Whether presented in the images of multinational corporations, polluted oceans, or vast climatic changes, hugeness is the signature of the absent god. Or, let us say that the divine attributes of Omnipotence, Omniscience, and Omnipresence alone remain. Without the benevolent governance of qualifying divinities, Omnipotence, Omniscience, and Omnipresence become gods. In other words, without the gods, the Titans return.

Are we re-enacting the beginnings of things as recounted by the Theology of Hesiod? The first great task of the gods was to defeat the Titans and to thrust them in Tartarus where they were to be kept away from the human earth forever. Zeus then married Metis (intelligence or measure); lay with Themis (who bore him Hours, Order, Justice, Peace, and the Fates); lay with Eurynome, through whom came the Graces; with Mnemosyne, mother of the Muses, and with Leto, mother of Apollo and Artemis. These archetypal principles and powers come into the world only when titanism is safely kept at bay. The cultured imagination and the imagination of civic order begins only when excess is encompassed.

Titans were imagined as Giants; in fact, the popular imagination, says Roscher, never distinguished between Giants and Titans. The root of the word titan means: to stretch, to extend, to spread forth, and to strive or hasten. Hesiod’s own etymology (Theogony 209) of titenes is “to strain.” This straining, striving effort suggests that the major contemporary complaint of stress is the feeling in the Promethean ego of its titanism. (Prometheus is perhaps the most well-known of the Titans, the figure whom Kerényi has called “the archetype of human existence,” thereby pointing to the titanic propensity in each of us.) Stress is a titanic symptom. It refers to the limits of the body and soul attempting to contain titanic limitlessness. A true relief of stress begins only when we can recognize its true background: our titanic propensity.

We may note a difference between titanism and hubris. Hubris is a human failure to remember the gods. When we forget or neglect the gods, we extend beyond the limits set by the gods on mortals, limits given mainly by Zeus through his union with Metis, Themis, and Mnemosyne.

Titanism, however, takes place at the level of the gods themselves. We are not Titans nor can we become titanic – only when the gods are absent can titanism return to the earth. Do you see why we must keep the gods alive and well? Small is beautiful requires a prior step: the return of the gods.

***

“Despite evidence of flagrant titanism all around us, the Titans themselves are invisible, like the black night sky of Uranos, their terrible father, and hidden by their mother, Gaia, in her deepest womb. They are sometimes imagined as ghosts. They work invisibly in darkness and in the impulses and fantasies arising from the depths. López-Pedraza points out, referring to the mythologists Nilsson and Kerényi, that the Titans – because they are invisible or unimaged – therefore do not have limits. Without image they become pure expansion. Hence, their punishment requires severe limitations: the chains that bind Prometheus; incarceration in Tartarus.

Limitation in our society tends to mean repression. We imagine the defeat of excess by means of tougher laws, harder education, severer systems of management control. However, the cure of enormity through more discipline is but an allopathic measure, a cure through the opposite which often leads to a righteous puritanical totalitarianism. The correction of one titanism can easily convert into another sort, e.g., totalitarian moralism, unless we understand what Zeus is truly about: the ordering power of the differentiated imagination: polytheism.

***

“Though the Titans may be invisible, an unimaged limitless greed locked inside human nature, titanism is all around. It strikes the ears, the membranes and eyeballs and fingers. Our senses touch and recoil. Repulsed by the huge and the ugly, we close off the world. We grab a bite on the run, drive thru our days. The common world is lost to sense, and too, the words of sense, the common descriptive language of adjectives and adverbs that give texture and shading. Instead, a titanism of acronyms and the justification for the ugly and the huge with abstract imageless reasons named economy, practicality, time-saving, comfort, accessibility, convenience, and national security.4

In this excerpt Hillman provides further signifiers for the titanic impulse, each associated with an outcome of formless excess; specifically the expansive, striving, spreading, straining and stretching toward outcomes of hugeness and enormity, ultimately to demonstrate what existence looks like without boundaries or limits.

Lastly, I will take five popular dictionary definitions of titanism for added detail, which are as follows:

- Oxford: 1. An attitude of resistance to, or defiance of, the established order of things; especially one which is grandiose or romantic but ultimately futile. Compare note at “Titan”. 2. The quality or fact of being titanic; very great size or power.

- Mirriam-Webster: Defiance of and revolt against social or artistic conventions

- Collins: A spirit of defiance of and rebellion against authority, social convention, etc.

- Dictionary.com: Revolt against tradition, convention, and established order.

- Thefreedictionary.com: Revolt against tradition, convention, and established order.

Summary

Based on the descriptions above we can now distil a summary of the traits associated with Titans, and the behavior titanism, with its driving impetus toward chaos: Titanism represents the drive towards destruction of established structures, in both self and society, in preference for a state of excessiveness, anarchy and chaos.

That, then, is the definition of titanism based on the above sources. While the overall picture remains one of destructiveness, it should also be noted that the Titans of mythology inaugurated a levelled landscape, a kind of tabula rasa on which the Olympians could move in and build their social order. In this sense titanic forces might be understood to preside over the process of entropy that works to break down established structures after they become encrusted and repressive – an impetus formalized in today’s philosophical obsession with deconstructionism and post-structuralism. Ultimately such shifts represent phases of the civilizational cycle, preferably short lived in duration thus minimizing the suffering that is always associated with violence and breakdown.

We’ve seen the titanic drive emerge at numerous points throughout history, especially in the closing phases of empires. We are witnessing it again in the West today within trends that are overtly violent or alternatively disguised behind a highbrow philosophical veneer of postmodern deconstructionism — which serves as camouflage for that same naked impulse toward destruction and chaos. We are witnessing the end of many things we took for granted: architectural uniformity, responsible individualism, free speech, self-restraint, modesty, manners, social hierarchy, familiar understandings of gender, family cohesiveness, national pride, and many other structures previously enjoyed as norms.

As social unrest increases and our streets continue to burn, we can hope that a well prepared Olympian family awaits in the wings to address the chaos, preferably sooner rather than later.

Sources:

[1] David L. Miller, The New Polytheism: Rebirth of the Gods and Goddesses, (1974)

[2] Hesiod: Theogony, Works and Days, Translated by A. Athanassakis, (1983)

[3] Rafael Lopez Pedraza, Cultural Anxiety, (1990)

[4] James Hillman, And Huge Is Ugly: Zeus and the Titans, in Mythic Figures, (2007)

In a

In a