Romance (n.)

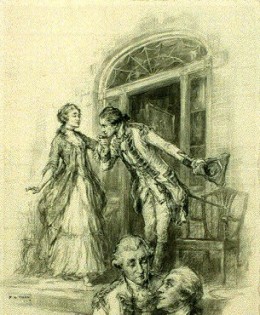

c. 1300, romaunce, “a story, written or recited, in verse, telling of the adventures of a knight, hero, etc.,” often one designed principally for entertainment, from Old French romanz “verse narrative.” This sense obviously included the love aspect of adventures; Lancelot and Guinivere, Tristan and Iseult, etc.

c. 1600s romaunce or romance narrowed to “a love story, the class of literature consisting of love stories and romantic fiction.”

c. 1700 extended as ‘romantic love,’ alternatively rendered ‘romantick love.’

The meaning of the phrase romantic love is a tangled one, however some of the first uses of it in English can be traced back to around 1700 when it was coined to refer to Don Quixote and his adventures in chivalric love. Suffice to say the medieval trope is there at the beginnings of this English phrase. Below are some early examples (and descriptions) of romantic love in English literature. Note the continuity of courtly love themes from the Middle Ages such as belief in the purity of women and their moral elevation above men, along with male supplication, chivalry, long-suffering, and of the ultimate extravagance of love. Below is a history of the english phrase ‘romantic love,’ which had equivalent counterparts in older French and German languages. The phrase and concept of romantic love is often wrongly conflated with the romantic period or “romanticism” which spanned from 1798 — 1750; however the phrase romantic love is clearly older and independent of the romantic period, as demonstrated in the samples below from almost a century prior to romanticism (eg. beginning of 1700s):

_________________________________________

Romantic love

1700:

“Many men being still of the opinion that the wonderful declaration of Spanish bravery and greatness in this lost century may be attributed very much to his carrying the jest too far, by not only ridiculing romantic love and errantry, but by laughing them also out of their honour and courage.” [The History of the Renown’d Don Quixote de la Mancha, 1700]

1705:

May for their sakes thier women are bullies prov’d, who walk the streets with wild romantick love, and cuckold their husbands in each others’ sight. [The Dutch Deputies. A Satyr. Quid non Batavia Fecit]

1720:

“And do you think, said his father changing his tone, I shall have the complacence to approve this romantic love of yours…” [A Select Collection of Novels: Don Carlos]

1734:

“Fill’d with romantick love Sir John began to sigh,

Thought he must love, but knew not what, nor why,

Still he read on, and still encreas’d his flame,

And found that each knight-errant had his dame

What shou’d he do alone without a fair?

Just at the nick o’ time, ‘with wond’rous air,

Sultan with broom was sweeping down her stair,

Sir John was smitten with a pleas’d surprize,

And face imaginary charms arise,

New beauties at each look their sweets diffuse,

Here the white lily, there the blushing rose;

In short—to Sultan he reveal’d his love,

Which the coy cunning reply did improve,

‘Till with intrigue he stole his fatal curle,

To sucky ty’d for better and for worse.

Soon marry’d, the succeeding honey-moon,

As it too often proves, was over soon;

He views his wife, not at her view’d his maid,

The lilies vanish, and the roses fade;

Discords, (as discords will in marriage rise)

From morn to evening fill the boufe with noise:

Poor Ladyship, to hinder wars to come,

Renews the operation of her Broom;

The Knight too late convinc’d by aching side,

She who could brush his hairs, could brush his hide.” [The London Magazine, Or, Gentleman’s Monthly Intelligencer]

1737:

“Farewell, farewell forever. She left me, with how much concern upon my heart, as it was beyond what I ever felt, it is beyond what I can ever express. Tho’ I was assur’d her reproach was unjust, yet from the principles of affection that gave occasion to it, it affected me. I struggled long between romantic love and prudent conduct: one day I resolv’d to fling myself at her feet the next, and give a proof of my love by ruining myself in marriage ; but the next I thought it better to see her Father again, and strive if…” [The London Magazine; Or, Gentleman’s Monthly Intelligencer, 1737]

1741:

“But I think the tragedy may receive a wonderful force, should its authors, without minding that giddy Romantic Love which makes such havoc in their plays, follow only the true philosophic Ideas of antiquity.” [An historical and critical account of the theatres in Europe, Luigi Riccoboni – Printed for T. Waller, 1741]

1742:

“And where’s the diff’rence twixt old age,

and youth worn out in its first stage,

No longer to apologize,

ye husband’s aged, rich and wise,

Dread twice to court the nuptial state,

and from the sequel mark your fate,

Ye Quixotes in romantic love,

Platonic cuckoldom improve.”

[A Wife and No Wife: the Mad Gallant, an Humorous Tale of Lunacy, Love and Cuckoldom]

1749:

“This novel is altered from one published in the year 1762 The Author, perceiving many material defects in the original work, particularly that the story was too simple to be very interesting, too concise to admit of much exemplification of character, and too much in the usual strain of romantic love.” [The Monthly Review, Volume 53, Ralph Griffiths, George Edward Griffiths, 1749]

1761:

“There is no resisting the impetuosity of romantic love. Like enthusiasm it breaks through all the restraints of nature and custom and enables, as well as animates its votaries, to execute all its extravagant suggestions ” [The World – by Adam Fitz-Adam, by Edward Moore, publishe by R. and J Dodsley 1761]

1773:

“The adventures of the Spanish knight [Don Quixote] were written to expose the absurdities of romantic chivalry, so those of the English heroine were designed to ridicule romantic love, and to show the tendency that books of knight-errantry have to turn the heads of their female readers.” [The Critical Review, Or, Annals of Literature, Volume 35, W. Simpkin and R. Marshall, 1773]

1776:

“Reading books of extravagant poetry raises corresponding doubt’s in the mind as they paint all the passions immoderate. Tragedies, such as they frequently are; books of romantic love, and which is fifty times worse, books of romantic intrigues, all tend to disturb the breast of the tender fair one.” [The Lady’s Magazine; Or, Entertaining Companion for the Fair Sex, Appropriated Solely to Their Use and Amusement, Volume 7, G. Robinson, 1776]

1777:

“Romantic love seems to be almost peculiar to the latter ages. This passion may perhaps be traced up to that spirit of courtesy and adventure which arose from circumstances peculiar to feudal government, distinguished all the institutions of chivalry, gave birth and form to the old romance, and consequently to the new, and to this day influences in a perceptible degree the customs and matters of Europe.” [Essays on the Nature and Immutability of Truth, 1777]

1777:

“In this correspondence the two friends encourage each other in the [……] notions imaginable. They represent romantic love as the great important business of human life, and describe all the other concerns of it as too low and paltry to merit the attention of such elevated beings, and fit only to employ the daughter of the plodding vulgar.” [The Universal Magazine of Knowledge and Pleasure, Pub. for J. Hinton, 1777]

1787:

“The romantic love, peculiar to the ages of chivalry, was readily united with the high sentiments of military honour, and seem to have promoted each other.” [An Historical View of the English Government From the Settlement of the Saxons in Britain to the Accession of the House of Stewart]

1787:

“The customs of duelling, and the peculiar notions of honour, which have so long prevailed in the modern nations of Europe, appear to have arisen from the same circumstances that produced feudal institutions: That same institution produced the romantic love and gallantry, by which the age of chivalry was no less distinguished…” [The Critical Review, Or, Annals of Literature, Volume 63, 1787]

1798:

“I readily grant that in former times this veneration for personal purity was carried to an extravagant height, and that several very ridiculous fancies and customs arose from this. Romantic love and chivalry are strong instances of the strange vagaries of our imagination, when carried along by this enthusiastic admiration for female purity; and so unnatural and forced, that they could only be temporary fashions. But I believe that, for all their ridicule, it would be a happy nation where this was the general creed and practice.” [Proofs of a Conspiracy against all the Religions and Governments of Europe, by John Robison, Philadelphia, 1798]