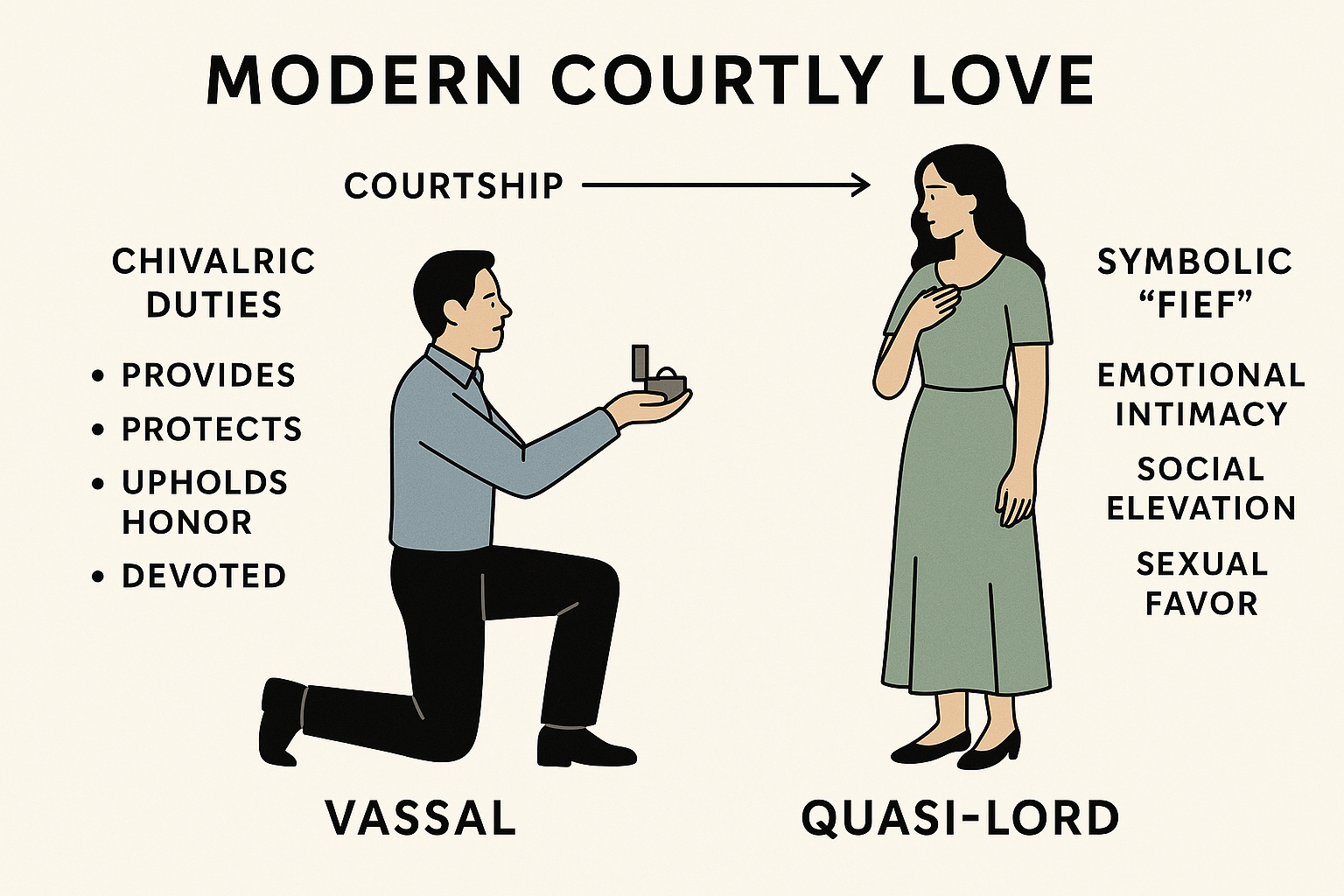

In the courtly love tradition, a man ceremonially placed himself in service to his Lady, much like a vassal did to a Lord. This included ritualized gestures of humility, loyalty, and submission. Modern relationships, especially traditional or romantic ones, retain surprising remnants of this.

Under the conventions of courtly love, the male lover or poet was often portrayed as a vassal, and the Lady was imagined as a quasi-Lord (or “Domina”). This metaphorical feudal relationship was central to the ideology of courtly love, which borrowed heavily from the hierarchical and ritualized structures of feudalism. Here’s how it worked:

Courtly Love as Feudal Allegory

-

The Male Lover (Poet/Knight): Seen as a vassal, who owed loyalty, service, and suffering to his Lady.

-

The Lady (Domina): Played in the role of a Lord (sometimes even superior to a feudal lord), who held power over the lover’s emotional and spiritual fate.

The “Fief” She Gave

In this metaphorical framework, the Lady bestowed a kind of “fief” or reward, but not land or wealth—rather, symbolic or emotional favors, which could include:

| Symbolic “Fief” or Reward | Meaning |

|---|---|

| A glance or smile | Acknowledgment of the male lover’s devotion |

| A token (e.g. a glove, handkerchief) | A physical sign of favor, often worn by the knight in battle |

| A spoken word or praise | Moral encouragement and validation of the male lover’s suffering |

| Permission to love her from afar | The basic premise of courtly love; often unrequited |

| A secret meeting | An ultimate favor, though often still chaste or coded |

| Physical & sexual intimacy | Especially later variants of courtly love |

Additional Key Features of This Relationship

-

The lover suffers nobly and serves loyally, often without hope of consummation.

-

The Lady is held on a pedestal, sometimes unattainable due to marriage, status, or chastity.

-

The relationship is often secret, idealized, and ritualized, mirroring both feudal duty and religious devotion.

Literary Examples

-

In troubadour poetry (11th–13th c. Provence), the language of fealty and homage is explicitly used as guides for male behavior.

-

In works like Chrétien de Troyes’ “Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart,” Lancelot’s servitude to Guinevere mirrors this vassal-lord model.

-

Andreas Capellanus’s “The Art of Courtly Love” even includes stages of love resembling steps of feudal progression.

In short: the lover is metaphorically a vassal, and the Lady a quasi-Lord. Her “fief” is not land or material goods, but tokens of emotional, sexual or symbolic favor, the currency of love within this cultural framework.

1. Modern Courtship Rituals as Echoes of Courtly Commendation

In the courtly love tradition, a man ceremonially placed himself in service to his Lady, much like a vassal did to a Lord. This included ritualized gestures of humility, loyalty, and symbolic submission. Modern relationships, especially traditional or romantic ones, retain surprising remnants of this.

Courtly Commendation | Modern Romantic Rituals:

| Feudal/Courtly Act | Modern Parallel |

|---|---|

| Vassal kneels before his Lord or Lady | Man kneels to propose marriage |

| Swearing oaths of loyalty and service | Exchanging vows, promises of lifelong love, fidelity, protection |

| Receiving a favor (token, cloth, smile) | Receiving a kiss, a smile, or a small gift as a “green light” |

| Formal public acknowledgment of the bond | Engagement announcement, wedding ceremony |

| Bearing the Lady’s favor in battle | Wearing wedding ring, tattoo of her name, publicly defending her honor |

| Lady as Domina—socially superior or idealized | “She’s out of my league” trope, male deference to her wishes |

These gestures remain highly gendered, with the man often initiating, petitioning, or pledging—a script that echoes homage to a Domina.

2. Modern Chivalric Roles in Relationships

Just as the medieval lover offered fealty, defense, and suffering, modern relationships often involve expectations placed particularly on men, especially in traditional or idealized pairings.

Chivalric Service | Contemporary Male Roles:

| Courtly Service | Modern Expectation |

|---|---|

| Knight’s duty to protect and serve | Man protects partner physically, emotionally, legally (e.g., home security, advocacy) |

| Material patronage | Man as breadwinner or provider, expected to offer financial or logistical support |

| Moral defense of her honor | Partner expected to defend her publicly (e.g., online harassment, family conflicts) |

| Emotional labor of devotion | Continuous demonstrations of loyalty, empathy, and attention |

| Suffering in silence for love | Withholding feelings, enduring stress silently to keep relationship stable |

These expectations persist even in many egalitarian relationships, often coded as “being a good man,” “a rock,” or “a real partner.”

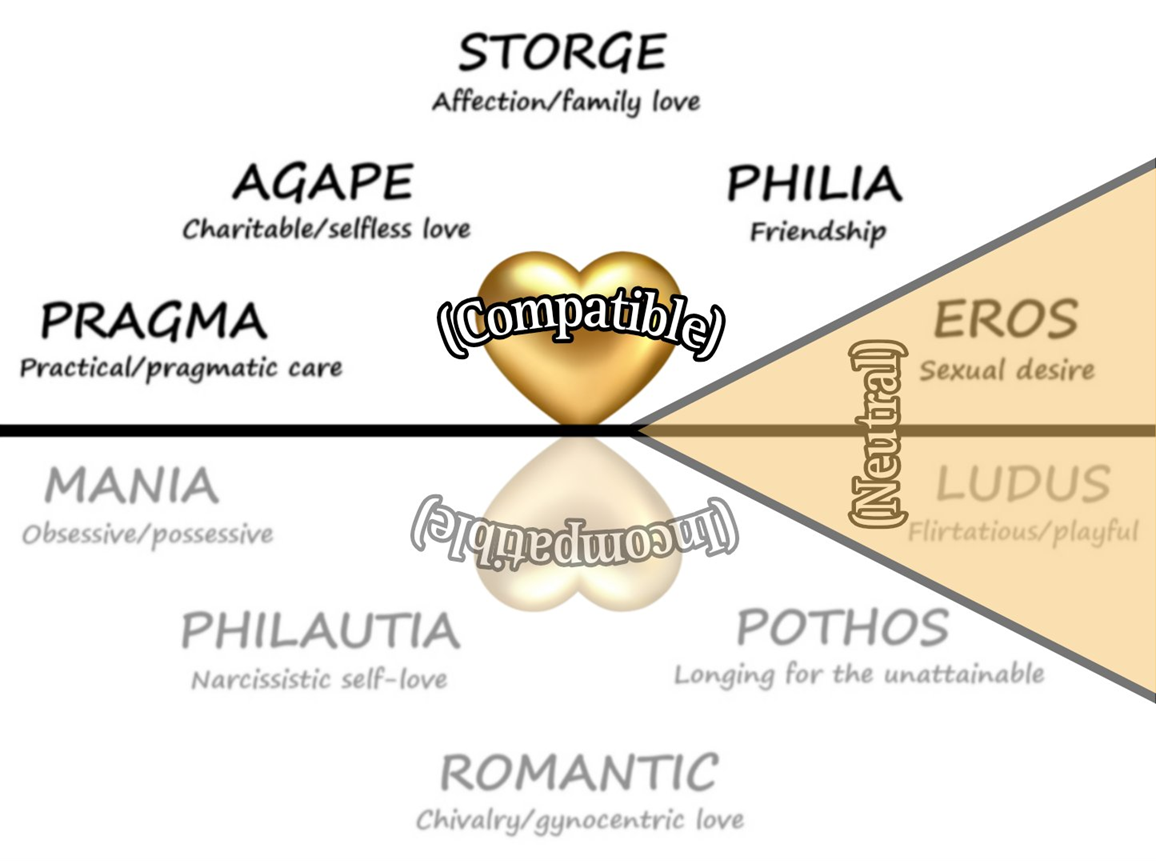

3. What Is the Modern Woman’s “Fief”?

If men are still metaphorically cast as vassals, what symbolic or emotional “fiefs” do women bestow in return today?

Non-Material “Fiefs” from Woman to Man:

| Fief Equivalent | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| Emotional intimacy | She grants emotional access, dispensation of affection, and bestows the sense of feeling needed |

| Sexual availability or favor | Still often framed as something “given” or “granted” in cultural narratives |

| Social elevation | He gains status or respect by being with her (beauty, prestige, admiration) |

| Validation and affirmation | Her approval affirms his identity as “worthy,” “manly,” or “successful” |

| Curated femininity (aesthetic effort) | Women’s gift of appearing beautiful, graceful, or socially elegant—coded as valuable, and raises the male profile |

| Emotional exclusivity or loyalty | She chooses him, which affirms his uniqueness (echoing the Lady’s selective gaze) |

In this model, the woman’s “fief” amounts to symbolic capital rather than material contributions; i.e., affection, beauty, approval, exclusivity, and sometimes sex are often idealized and rationed to match his displays of service.

Why This Persists

-

Romanticism (18th–19th centuries) absorbed and rebranded courtly love ideals as aspirational rather than aristocratic.

-

Pop culture reinforces these dynamics through stories of chivalrous men and mysterious, enchanting women (Disney, rom-coms, music etc.).

-

Gender socialization still teaches men to prove themselves through action, and women to bestow value through selection.

Final Thought

While modern relationships are far more fluid, egalitarian, and varied than in the past, the ghost of courtly love remains strongly embedded in many scripts about love, courtship, and gender. Learning more about these echoes helps people choose which parts to honor, revise, or discard in their own partnerships.

___________________________________________

The above historical perspective and image generated by OPEN-AI.