By Douglas Galbi

Good lady, you may burn or hang him

or do anything you happen to desire,

for there’s nothing that he can refuse you,

as such you have him without any limits.{ Bona domna, ardre.l podetz o pendre,

o far tot so que.us vengua a talen,

que res non es qu’el vos puesca defendre,

aysi l’avetz ses tot retenemen. } [1]

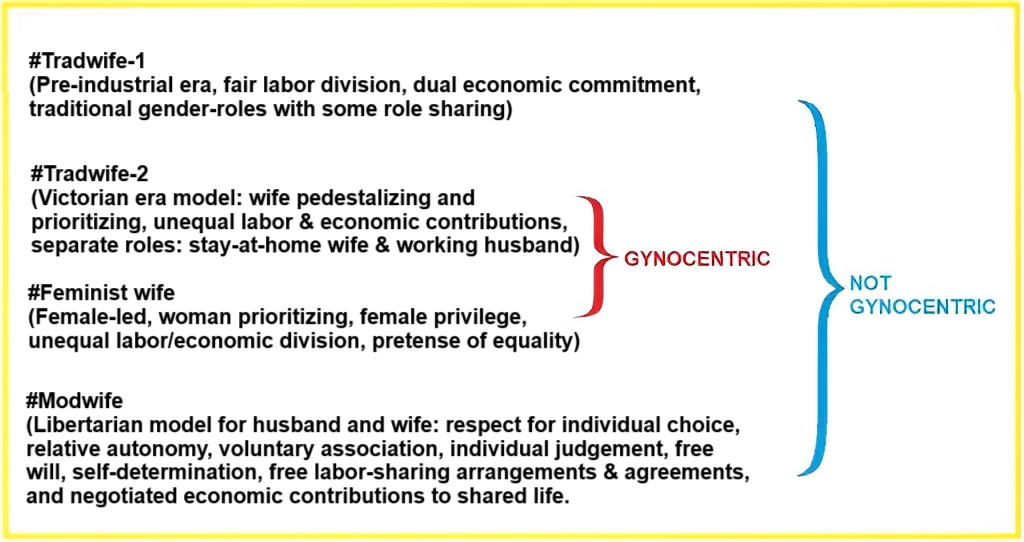

Men have long been sexually disadvantaged. While men’s structural disadvantages are scarcely acknowledged within gynocentric society, a small number of medieval women writers courageously advocated for men. In Occitania early in the thirteenth century, the extraordinary trobairitz Lady Castelloza spoke out boldly against gender inequality in love and men having the status of serfs in sexual feudalism.

And if she tells you a high mountain is a plain,

agree with her,

and be content with both the good and ill she sends;

that way you’ll be loved.{ e s’ela.us ditz d’aut puoig que sia landa,

vos l’an crezatz,

e plassa vos lo bes e.l mals q’il manda,

c’aissi seretz amatz. } [2]

Just as is the case for many women today, many medieval women didn’t adequately support and defend men. When Giraut de Bornelh asked his lovely friend Alamanda about his love difficulties, she advised him to be totally subservient to his lady. Alamanda was a maiden to that lady. Lord Giraut apparently had lost his lady’s love by seeking sex with a woman who was not her equal, probably none other than her maiden Alamanda. But what had that lady done to him? She had lied to him at least five times before! When women speak, men should not just listen and believe. Unwillingness to question a woman led a Harvard Law professor to personal disaster. Men should not act as doormats for women or as women’s kitchen servants.

The trobairitz Maria de Ventadorn insisted to Gui d’Ussel that a woman should retain her superior position even in a love relationship with a man. Gui felt that men and women in love should be equals. But Maria wanted men to fulfill all the pleas and commands of their lady-lovers. That’s the pernicious doctrine of yes-dearism. Just say no to female supremacists!

Lady {Maria de Ventadorn}, among us they say

that when a lady wants to love,

she should honor her love on equal terms

because they are equally in love.

…

Gui d’Ussel, at the beginning lovers

say no such thing;

instead, each one, when he wants to court,

says, with hands joined and on his knees:

“Lady, permit me to serve you honestly

as your servant man” and that’s the way she takes him.

I rightly consider him a traitor if, having given

himself as a servant, he makes himself an equal.{ Dompna, sai dizon de mest nos

Que, pois que dompna vol amar,

Engalmen deu son drut onrar,

Pois engalmen son amoros!

…

Gui d’Uissel, ges d’aitals razos

Non son li drut al comenssar,

Anz ditz chascus, qan vol prejar,

Mans jointas e de genolos:

Dompna, voillatz qe-us serva franchamen

Cum lo vostr’om! et ella enaissi-l pren!

Eu vo-l jutge per dreich a trahitor

Si-s rend pariers e-s det per servidor. } [3]

Because of their great love for women, men are reluctant to demand that women treat them with equal human respect and dignity. Men tend toward gyno-idolatry. The man on his knees before a woman, with his hands clasped, is making a gesture of faithful subordination. She then puts her hands around his hands to complete this feudal gesture known as the immixtio mannum {intermingling of hands}. A man today who goes down on his knee to ask a woman for her hand in marriage is preparing to be a vassal to his woman-lord midons. That’s folly. That’s fine preparation for a sexless marriage. From studying Ovid the great teacher of love to modern empirical work on sexual selection, men should know that self-abasement is a losing love strategy.

Oh Love, what shall I do?

Shall we two live in strife?

The griefs that must ensue

would surely end my life.

Unless my Lady might

receive me in that place

she lies in, to embrace

and press against me tight

her body, smooth and white.

…

Good Lady, thank you for

your love so true and fine;

I swear I love you more

than all past loves of mine.

I bow and join my hands

yielding myself to you;

the one thing you might do

is give me one sweet glance

if sometime you’ve the chance.{ Amors, e que.m farai?

Si garrai ja ab te?

Ara cuit qu’e.n morrai

Del dezirer que.m ve,

Si.lh bela lai on jai

No m’aizis pres de se,

Qu’eu la manei e bai

Et estrenha vas me

So cors blanc, gras e le.

…

Bona domna, merce

Del vostre fin aman!

Qu’e.us pliu per bona fe

C’anc re non amei tan.

Mas jonchas, ab col cle,

Vos m’autrei e.m coman;

E si locs s’esdeve,

Vos me fatz bel semblan,

Que molt n’ai gran talan! } [4]

The medieval trobairitz Castelloza sympathized with men’s subordination in love. She loved a man who didn’t love her. A woman today in such a situation might open a dating app and enjoy a huge number of solicitations from men. Then, if necessary to boost her self-esteem, she might go for sexual flings with a few, or at least exploit traditional anti-men gender dating roles to get some free dinners. With a keen sense for social justice, Castelloza refused to live according to such female privilege:

I certainly know that it pleases me,

even though people say it’s not right

for a lady to plead her own cause with a knight,

and make long speeches all the time to him.

But whoever says this doesn’t know

that I want to implore before dying,

since in imploring I find sweet healing,

so I plead to him who gives me grave trouble.{ Eu sai ben qu’a mi esta gen,

Si ben dison tuig que mout descove

Que dompna prec ja cavalier de se,

Ni que l tenga totz temps tam lonc pressic,

Mas cil c’o diz non sap gez ben chausir.

Qu’ieu vueil preiar ennanz que.m lais morir,

Qu’el preiar ai maing douz revenimen,

Can prec sellui don ai greu pessamen. } [5]

Castelloza recognized that, in pleading with a man for love, she was transgressing the norms of men-oppressing courtly love. When women treat men merely as dogs, women don’t experience the full gift of men’s tonic masculinity. The master dehumanizes herself in dehumanizing her man-slaves. Castelloza, in contrast, understood that a man’s love can ennoble a woman. She understood that a man can offer much to even the most privileged woman.

I’m setting a bad pattern

for other loving women,

since it’s usually men who send

messages of well-chosen words.

Yet I consider myself cured,

friend, when I implore you.

for keeping faith is how I woo.

A noble women would grow richer

if you graced her with the gift

of your embrace or your kiss.{ Mout aurei mes mal usatge

A las autras amairitz,

C’hom sol trametre mesatge,

E motz triaz e chauzitz.

Es ieu tenc me per gerida,

Amics, a la mia fe,

Can vos prec — c’aissi.m conve;

Que plus pros n’es enriquida

S’a de vos calqu’aondansa

De baisar o de coindansa. } [6]

Men’s lack of imagination and unwillingness to protest helps to keep them in their gender prison of gynocentrism. Men rightly appreciate, admire, and love courageous, transgressive women like the trobairitz Castelloza. But men must take responsibility for winning their own liberation. A man showing loving concern about his close friend getting married isn’t enough. Men should be more daring and, like Matheolus, raise stirring voices of men’s sexed protest. Men Going Their Own Way (MGTOWs) struggled against misandry and castration culture even in the Middle Ages, and they continue to do so today. MGTOW is merely prudent personal action. To dismantle gynocentric oppression, men must recover, create, and disseminate protest poetry as potent as the medieval troubadours’ feudal songs of men’s love serfdom.

Peire, if spanning two or three years

the world were run as would please me,

I’ll tell you how with women it would be:

they would never be courted with tears,

rather, they would suffer such love-fears

that they would honor us,

and court us, rather than we, them.{ Peire, si fos dos ans o tres

Lo segles faihz al meu plazer,

De domnas vos dic eu lo ver:

Non foran mais preyadas ges,

Ans sostengran tan greu pena

Qu’elas nos feiran tan d’onor

C’ans nos prejaran que nos lor. } [7]

* * * * *

Notes:

[1] Domna and Donzela, “Bona domna, tan vos ay fin coratge” ll. 17-20, Occitan text and English translation (modified insubstantially) from Bruckner, Shepard & White (1995) pp. 92-3. Here’s some meta-data about this trobairitz song. It’s a debate poem (tenso). The currently best critical edition of trobairitz / troubadour tensos is Harvey, Paterson & Radaelli (2010), but it’s expensive and not widely available. For analysis of the genre of tenso, McQueen (2015).

[2] Alamanda and Giraut de Bornelh, “S’ie.us qier conseill, bella amia Alamanda” ll. 13-16, Occitan text and English translation from Bruckner, Shepard & White (1995) pp. 42-3.

[3] Maria de Ventadorn and Gui d’Ussel, “Gui d’Ussel be.m pesa” ll. 25-8, 33-40, Occitan text and English translation (modified insubstantially) from Bruckner, Shepard & White (1995) pp. 38-41. This poem is also available in translation in Paden & Paden (2007). The immixtio manuum isn’t attested prior to 1100. West (2013) p. 211.

[4] Bernart de Ventadorn, “Pois preyatz me, senhor” ll. stanzas 4 & 6, Occitan text and English translation by W.D. Snodgrass from Kehew (2005) pp. 84-5. The Poemist offers online the full text and English translation.

Men’s abasement in sexual feudalism is pervasive in trobairitz song. Men engage in gyno-idolatry and imagine that they will die without a woman’s love:

I bow down to you, whom I love and adore,

and I am your liegeman and your household servant.

I yield myself up to you, who are the noblest

and the best being that was ever born of a mother.

And since I cannot help but love you,

for mercy’s sake, I beg you, don’t let me die.{ Sopley vas vos, cuy yeu am et azor,

E suy vostres liges e domesgiers.

A vos m’autrey, qar etz la genser res

E la mielhers qu’anc de maire nasques.

E, quar no.m puesc de vos amar suffrir,

Per merce.us prec que no.m layssetz morir. }

Peire Bremont Ricas Novas, “Us covinens gentils cors plazentiers,” 3.3-8, Occitan text and English translation (modified) from Kay (1999) p. 217. Peire Bremont Ricas Novas was active in Province from about 1230 to 1241.

[5] Na {Lady} Castelloza, “Amics, s’ie.us trobes avinen” ll. 17-24 (stanza 3), Occitan text from Paden (1981), English trans. (modified) from Paden & Paden (2007). Bruckner, Shepard & White (1995) provides a slightly different Occitan text and English translation of all of Castelloza’s songs. Butterfly Crossings provides an online Occitan text and English translation of the full song, with commentary. Her commentary puts forward orthodox myth in service of gynocentrism:

by virtue of being a woman she is below him socially, thus rendering her statement simultaneously true and drawing attention to the place of women in society as opposed to the artificial pedestal they sit upon in traditional Troubadour poems. Regardless of her title, class, or wealth, in love, much like in life, the woman is beneath the man and must beg his favor like Castelloza here does.

Yup, so Anne of France was beneath day-laboring men gathering stones in fields.

Much influential recent scholarship on trobairitz has been based on dominant gender delusions. A relevant critique:

Gravdal’s argument here is based on her assumption that, for the men, powerlessness is a pose, a rhetorical strategy; the male speaker adopts an abased position only to use it as a springboard to higher status and sociopolitical clout. That Castelloza’s speaker does this as well is frequently overlooked, because it is assumed that for the women, powerlessness is a reality. This assumption is not supported by the evidence for noblewomen’s sociopolitical situation in Occitania during the time of the trobairitz.

Langdon (2001) p. 40.

[6] Castelloza, “Mout avetz faich lonc estatge” ll. 21-30 (stanza 3), Occitan text from Paden (1981), English trans. (modified) from Paden & Paden (2007). Butterfly Crossings again offers the full song, along with commentary. The commentary shows orthodox academic failure of self-consciousness:

Almost smirkingly Castelloza acknowledges that her behavior sets a terrible example for all other female lovers while synchronously encouraging them to do the same. She is not apologizing as much as drawing attention to the solidarity between women who will now partake in this perhaps liberating behavior and act upon their desires as opposed to remaining within the confined roles of passive love interests.

Women unite in liberating behavior: ask men out and buy men dinner!

In Castelloza’s songs, the man she loves has neither voice nor activity. Siskin & Storme (1989) pp. 119-20. Self-centeredness is a common characteristic of women’s writing, particularly in the last few decades of literary scholarship.

[7] Peire d’Alvrnha (possibly) and Bernart de Ventadorn, “Amics Bernartz de Ventadorn,” stanza 4, Occitan text from Trobar, my English translation benefiting from that of Rosenberg, Switten & Le Vot (1998). James H. Donalson provides an online Occitan text and English translation for the full song.

Bernart de Ventadorn was one of the greatest troubadour love poets. His desire for women to experience men’s subordinate position in love is coupled with appreciation for gender equality and reciprocity in love:

The love of two good lovers lies

in pleasing and in yearning’s thrill

from which no good thing will arise

unless they match each other’s will.

The man was born an imbecile

who scolds her for her preference

or bids her do what she resents.{ En agradar et en voler

es l’amors de dos fi?s amants;

nulha res no·i pòt pro? tener

se·l volontatz non es egals.

E cell es be? fols naturals

qui de çò que vòl la reprend

e·ilh lauza çò qu no·ilh es gent }

“Chantars no pot gaire valer,” Occitan text and English trans. (modified insubstantially) from A.Z. Foreman. For an alternate English translation, Paden & Paden (2007) pp. 74-5. While Bernart here unequally criticizes men, in an earlier stanza her criticized women whoring in loving men.

[images] (1) Na Castelloza. Illuminated initial in manuscript Chansonnier provençal (Chansonnier K). Created in the second half of the thirteenth century. Folio 110v in Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF) MS. 12473. (2) Immixtio manuum: Feudal tenant show faithful subordination to a procurator of King James II of Majorca in Tautaval. Illumination made in 1293. Preserved as Archives Départementales de Pyrénées-Orientales 1B31.

References:

Bruckner, Matilda Tomaryn, Laurie Shepard, and Sarah White, eds. and trans. 1995. Songs of the Women Troubadours. New York: Garland.

Harvey, Ruth, Linda M. Paterson, and Anna Radaelli. 2010. The Troubadour Tensos and Partimens: a critical edition. Cambridge: Brewer.

Kay, Sarah. 1999. “Desire and Subjectivity.” Ch. 13 (pp. 212-227) in Simon Gaunt and Sarah Kay, eds. The Troubadours: an introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kehew, Robert, ed. 2005. Lark in the Morning: the Verses of the Troubadours: a bilingual edition. Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Press.

Langdon, Alison. 2001. “‘Pois dompna s’ave/d’amar’: Na Castellosa’s Cansos and Medieval Feminist Scholarship.” Medieval Feminist Forum 32: 32-42.

McQueen, Kelli. 2015. That’s Debatable!: Genre Issues in Troubadour Tensos and Partimens. Thesis for Degree of Master of Music. Theses and Dissertations. Paper 819. The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

Paden, William D. 1981. “The Poems of the Trobairitz Na Castelloza.” Romance Philology. 35 (1): 158-182.

Paden, William D., and Frances Freeman Paden, trans. 2007. Troubadour Poems from the South of France. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer.

Rosenberg, Samuel N., Margaret Louise Switten, and Gérard Le Vot. 1998. Songs of the Troubadours and Trouvères: an anthology of poems and melodies. New York: Garland Pub.

Siskin, H. Jay and Julie A. Storme. 1989. “Suffering Love: The Reversed Order in the Poetry of Na Castelloza.” Ch. 6 (pp. 113-127) in Paden, William D., ed. The Voice of the Trobairitz: perspectives on the women troubadours. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania.

West, Charles. 2013. Reframing the Feudal Revolution: political and social transformation between Marne and Moselle, c. 800 – c. 1100. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press.

*Article licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0