Over recent centuries women have encouraged men to develop a more gynocentric focus, then apparently have gone on to despise them for it — according to a 1993 article published in the Canberra Times:

Month: June 2024

Kipling’s Modern Chivalry: Masculinity and War in The Light That Failed

The following abstract and sample is from an essay by Dennis Gouws, differentiating gynocentric chivalry from inter-male chivalry, aka brotherhood. The full essay is published in the book War, Espionage, and Masculinity in British Fiction edited by Susan L. Austin (2023).

* * *

Chapter 2

Kipling’s Modern Chivalry: Masculinity and War in The Light That Failed

Dennis S. Gouws

Springfield College

Abstract

This chapter begins with a discussion of how the concept of chivalry evolved, expanding beyond the nobility, and shaping standards of behavior for commoners who wished to establish themselves as English gentlemen. It then argues that chivalrous attitudes toward women and self-sacrifice prove futile and destructive for the male characters, while the chivalrous emphasis on brotherhood encourages positive bonds between them.

Keywords: Chivalry, English Gentleman, Manhood, Masculine Identity, Masculine Friendship, Rudyard Kipling

* * *

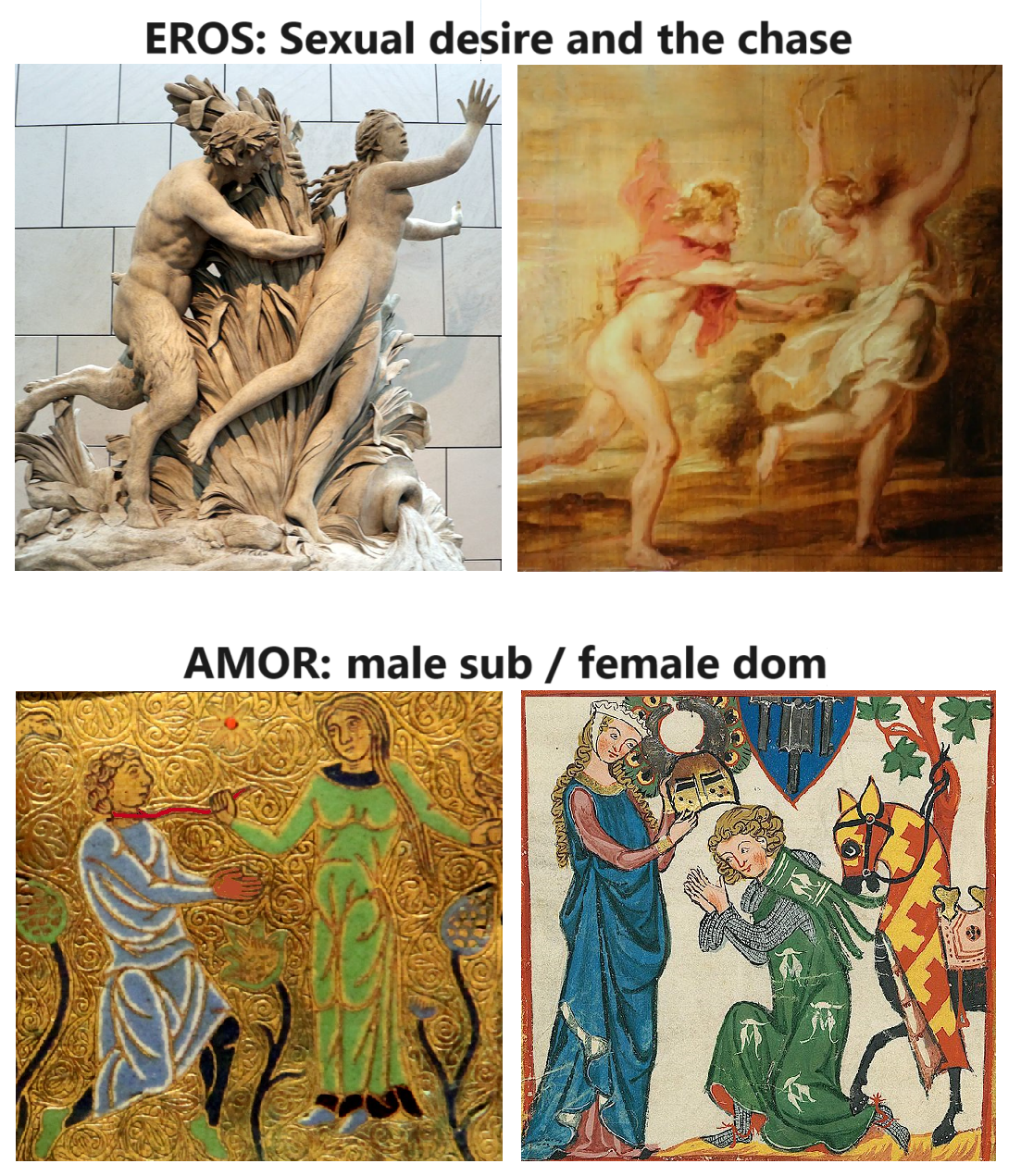

Excerpt: In The Light that Failed, Kipling questions the usefulness of nineteenth-century chivalry for guiding fin-de-siecle love and war and seems surprisingly modern in doing that. Examined from a twenty-first-century perspective, the usual chivalric love association described by Keen is too often a misandrist (male-hating) imperative, requiring men to internalize a toxic idea of themselves as a condition for finding love. Peter Wright astutely observes this kind of chivalry is “both sexist and gynocentric in nature, one that demands men provide numerous psychological gratifications and material benefits to recipient women;” he concludes, “The chivalric role offers heterosexual men a life-map to guide their social behaviour while providing a sense of self based on service to women” (56). Traditional chivalry has declined to gynocentric (woman-centered) service; consequently, it has little to offer twenty-first-century males. Kipling’s male contemporaries still willingly protected the weak; however, as the reader of The Light that Fails discovers, conventional chivalric courtship does not win the day in the author’s “originally conceived” (vii) fifteen-chapter version of the work (the different endings of the twelve-chapter Lippincott’s version and the longer MacMillan’s version will be discussed below). It is dramatized as humiliating rather than satisfying for the parties involved.

_______________________________

Most of this essay can be read on Google Books or the longer volume can be purchased at Amazon.

Family in Asia, versus family in the West

By Shu Yi

Family structure

Firstly a little bit of background: I’m in my mid-30s, I’m from China, and I also went to the west (Australia, New Zealand, US) to study in my late teens, and after that, came to Japan and have been living here ever since.

When I was a child every family I could see consisted, at minimum, of the children, parents, and the grandparents – i.e., the mother and father of either parent. (traditionally it was the father’s parents, but in practice it varies among households).

This is only the core family. Yes, that’s right, this does not include the usual ‘extended family’. It’s also common to have uncles and aunts who are still unmarried living together with the family, which in my house it was the case.

It was rare to see a family consisting only of the parents and children; in such cases they are often not locals of the city, but rather parents who moved there from another location in order to go to university, who then got a job and settled down there. Where are their grandparents? Still in their hometown, with other siblings still there with them, where it’s basically the same family structure as what I described in my own hometown above.

Young people who go to another city to work and settle, either bring their parents with them to the city or, after they have saved enough money, go back to live with their parents and build a new house where everybody can live. That’s right, there’s no shame in “still living with the parents” — it’s expected, and it’s the norm that parents and children are always immediate family members who live together.

The situation I have described is common in Asia. If you know the Japanese show Miss Sazae, Little Maruko, and Crayon Shinchan, they represent three common types of Japanese household (for reference, these are the iconic and longest running household shows in Japan, that represents everyday life).

Miss Sazae (started in 1946): the family consist of Miss Sazae, her husband, her parents, her younger brother and sister, and her son.

* * *

Little Maruko (since 1986): the family consist of the little girl Maruko, her sister, her parents, her paternal grandparents

* * *

Crayon Shinchan (since 1990): the family consist of a little Shinchan, his sister, and his parents. His parents are from rural areas of Japan, who settled in Greater Tokyo. They don’t live with grandparents. This represents the newer type of family structure. The mother’s older sister stays in their hometown with their parents, while the mother and the mother’s younger sister went to the city.

In fact, it is still the tradition in Japan that the eldest son or the eldest child do not ever leave the parents, this is the child that will get the inheritance, and has the responsibility to take care of the parents.

Childcare and senior care

China does not have daycare centres. The only time China had daycares was during the peak of the communist movement which aimed to abolish the family unit (so even without the communist name, I encourage you to consider the true nature of daycares).

China has kindergarten for children aged 3 and over, and the care of all younger children is done within the family. Parents go to work, while grandparents stay at home looking after the kids, doing the cooking and cleaning, and the parents take over these roles when they get home from work. I can’t help but feel like this probably was the arrangement throughout most of human history, with the young and strong parents going out to hunt/farm etc, with the children and elders staying in the home camp/house.

I touched on senior care above, and can characterise the grandparents as being an integral part of the immediate family. They usually live with one of their children. When I was little, for example, this was the case – and my grandmother even had her mother come and stay with us when necessary (she usually lived with her son, but her son was out of town for a few days).

Marriage

Semi-arranged marriage is very common, if not the majority. In China, young people are free to meet people on their own at university, work, etc, but as you can imagine, the success rate is not very high (I imagine the success rate is not that high for any culture by doing it this way). So a lot of people will have their parents arrange the marriage for them. The parents will try to find a suitable spouse through their friends, relatives (such as the relative’s friends/coworkers etc), and extended network — which means they know the potential spouse’s background, career, education, siblings, parents’ career etc, and the potential spouse also knows theirs.

If the young people find a girlfriend/boyfriend on their own, after dating for a while, they usually have to go through the same process of background checks, two sets of families meeting to discuss their future, including getting down to the finances, housing, etc. Therefore marriage is still very much between the two families, not just the two young people. Sometimes the parents will agree with them going forward and getting married, sometimes they don’t agree. By law, young people can still marry freely, but not many of them will want to go against their parents’ opinion because their own family is their ingroup, one that shares common interests with them, and provides valuable support.

It is unlikely for young people to value romantic love misadventures above family, as you could end up with no support (but ironically that level of ‘no support’ sort of just looks like the Western norm). On the other hand, you could argue this entire process is extremely unromantic, and I agree. It’s definitely not a “love at first sight, fall in love, throw away the world for you” kind of relationship. In Japan it’s more or less the same as in China; young people will try to find a spouse on their own from work, university, etc, they will also go to match making events (very popular), and their parents will also look for them.

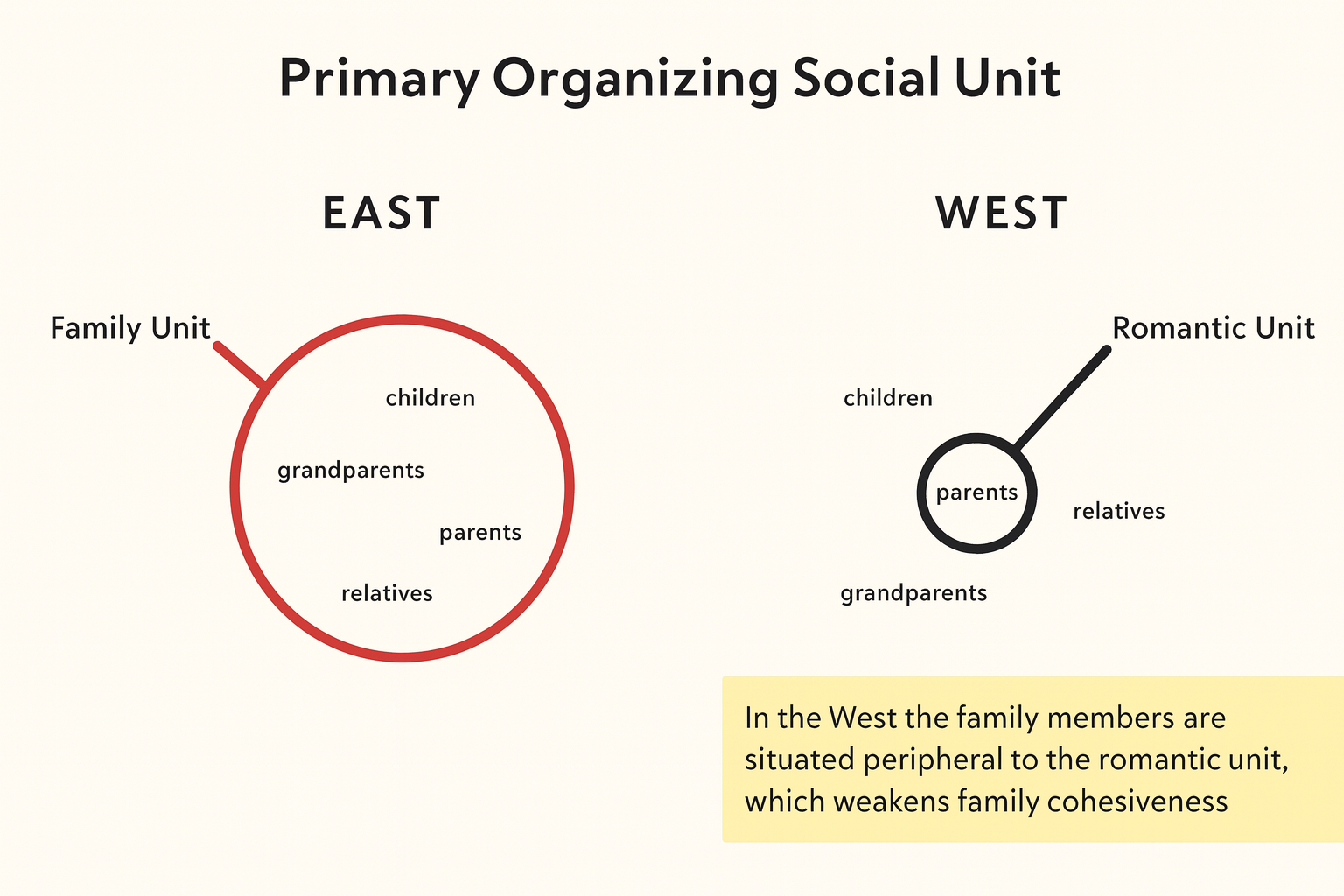

Who is the center of the family?

With this family structure, you absolutely cannot have the couple as the center and above all other family members and considerations. If you do that, the family will not work. It will crumble. When children are young, they are definitely in the center. When grandparents are old and sick, they are definitely the center. Things will be planned revolving around them, and sacrifices will be made for them; family caters to the most important needs of its members. The truth is, within a ‘big family’ (Westerners say big, I say normal sized), nobody discusses ‘the couple’ nor are they aware of it; everything is just intertwined. There’s no “date night” for couples; if you are going out to eat, everybody goes. If you go traveling, everybody goes. If you say ‘the couple is the center and most important’ in a big family, frankly, that is offensive to other family members. The family unit absolutely cannot be reduced further anymore.

So in that sense ‘the couple’ just doesn’t exist. Also, it is not the couple’s house, it’s everybody’s house. You absolutely cannot say ‘this is my house so you have to obey my rules’ (which I hear so often in the West), if you say that, it’s greatly offensive as it’s an implication of cutting family ties. Also, you are not validly in a position to say that, because most likely everybody pitched in financing for that house, and also contribute to make family life functional.

Family network

When the core family is as big as it is, and you have a lot more in the extended family, a lot of things are done within the family. If a distant family member graduated and is looking for a job, he will get one through family network. If you are feeling unwell, you can get a distant family member who’s a doctor to look at you. If you are looking at starting a business, make phone calls to see what distant family members are doing. You don’t know what major to choose in college? – then see if some family members already work in a certain area.

Westernization/communism dismantling

Despite preservation of strong family traditions in Asia, communism keeps trying to dismantle the family because if you make people more alone and isolated, they are easier to control. Family is the most innate and powerful thing for humans, as it counteracts forces that attempt to isolate and exploit them.

In China, there were movements and policies attempting to dismantle the family: their ideal is to have men, women, and children all living in a state of separation. Under this dystopian vision children are raised collectively by the state (so basically orphanages), and no such thing as family will exist. China tried that. And they are still trying it. Before, they tried that in the cities, now, they are pushing it in the rural areas.

It is illegal in China to move and reside freely without a residency permit. So when people from rural areas go to work in the cities, they can’t take their children with them. The family unit in China keeps facing crack downs by the government, and those who are aligned with communist values no longer believe in family relations, or family. Moreover, Westernization is having an effect (btw communism is also westernization as it literally came from the West). Some young people begin to like the more romantic ideas from the West, and they think the Asian traditional family is too “practical.” Some opinion leaders in Asia are pushing for a smaller nuclear family, and not living with parents, etc, saying this Western way is more advanced, and that the traditional Asian way is too old and outdated. Guess what? It’s not outdated.

To put this into perspective, what I’ve described here is not an ‘Asian vs. Western’ thing; it is instead ‘traditional vs. new’ – with the ‘new’ coming in the forms of communism, or romantic coupling respectively, both of which take a wrecking ball to traditional family. The traditional family I described is universally human, and still remains in many parts of the world. It’s just the West was modernized very early and has lost a lot more.