Leo Tolstoy gives his opinion on romantic love, printed in the Civil & Military Gazette (Lahore) – Friday 21 December 1888.

Author: gynocentrism

Gynocentrism In Marriage Counseling

Christian Churches Conflating Romantic Chivalry with Agape

Many Christian Churches have become temples to romantic love, which began as a worship of women in medieval times by poets and singers who celebrated romantic chivalry, a practice which elevated women to a quasi-divine status. This non-Christian tradition has gained a stranglehold over modern Church culture, to the extent that traditional Christian teachings are becoming obscured in its wake. The following illustrate some of the phenomena that have resulted:

Church and clergy often champion values of romantic love

Which encourages women to conflate Jesus’ love with romantic chivalry

And pressures men to conflate God’s love with romantic chivalry

We are seeing women go on romantic dates with Jesus.

And a growth in the genre of “Christian” romance novels

Also the rise of Christian wives requesting romantic “date nights” from husbands

And finally congregations are singing romantic love songs to God, making evangelical Church worship sound like a Justin Bieber concert encouraging people to “fall in love with, have a love affair with, or become passionate or intimate with Jesus,” while characterizing God as a romantic ravisher of our souls.

Romantic chivalry is a love that’s woman-centered, whereas agape is neighbor centered; Love thy neighbour as thyself. The battle between these two different loves is the crux of a war within the modern Church, because it ultimately confuses and conflates these two contrary motives. To put the problem simply: romantic gynocentrism is not agape.

Does any of this tell us why intelligent men are leaving the Church, and why new men are not coming into it? As always, I invite you be the judge.

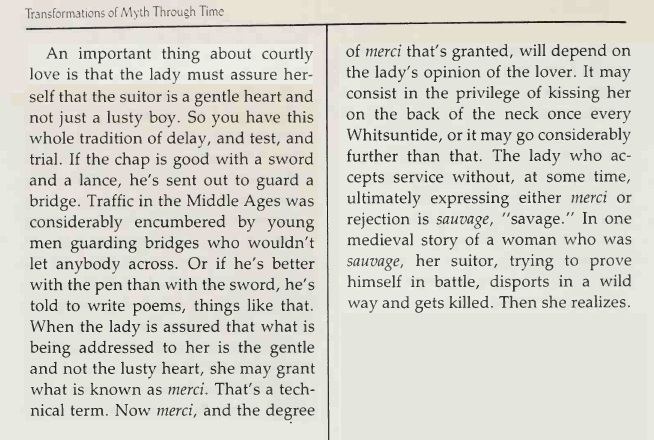

The Lady in romantic love exchanges may grant mercy, or be “savage”

‘The Henpecked Male’ by Hendrick de Leeuw (1957)

The following quotes are from the chapter ‘The Henpecked Male,’ in Woman: The Dominant Sex — by Hendrick de Leeuw (1957). In this volume deLeeuw joins the legions of early observers who rate America as the most gynocentric nation on earth, and in all of history, resulting in the proverbial henpecked man – PW

‘Shield of Parade’ representing chivalrous love (15th century)

The ‘Shield of Parade‘ is a 15th century artifact depicting a scene of chivalric love, which is currently housed in the medieval gallery of the British Museum.

The shield’s front panel portrays a youthful knight clad in battle armor. Genuflecting in a gesture of servitude toward the woman he loves, he grips a pole axe in one hand, while a sheathed sword rests at his side. Nearby, his helmet and gauntlets lie discarded. The figure of Death emerges from behind and gazes malevolently while reaching out to take the knight.

On the left side of the shield a noble lady stands projecting an air of arrogance. She is adorned in opulent attire, her gilded finery catching the light. A long hennin hat graces her head, its trailing silk veil draped own her back. Curiously, her facial expression conveys detachment, making her seem somewhat cold or dismissive to the dramatic scene unfolding before her.

A scroll of text floats above the knights head with the words “vous ou la mort,” which translates as “you or death” in French. These words reveal that this scene is one of chivalric love, in which the knight would happily die proving his love than to dishonor his lady and lose her love by his poor performances in battle.

A Values-Centered Approach to Gynocentrism

By Paul Elam

Eleanor Roosevelt is credited with saying ‘Great minds discuss ideas. Average minds discuss events. Small minds discuss people.’ It is a fantastic quote and I’d like to borrow from it and offer my own red pill spin: Great minds discuss gynocentrism. Average minds discuss feminism. Small minds discuss women.

When discussing a values-centered model in the context of gynocentric culture, I assume three states of being most typical to modern western men. Those are:

- Gynocentric

- Gynocentric Reactive

- Gynocentric Proactive

Gynocentric refers to the average man. He usually, but not always, operates with women unconsciously, just following whatever scripts he has adopted from early life. He seeks women’s acceptance without an intact set of values that are designed to protect him. In fact, it is his values that put him at risk. Many men value only being accepted sexually and romantically, by any woman they are attracted to, regardless of her moral character and any possible risk she represents.

The gynocentric man is the one with a piece of paper that says kick me taped to his back. We can mock him if we want, but we are well to remember that we have all been this man at one point or another in our lives.

Gynocentric Reactive is a much more complicated affair. Here we see men who are infinitely more conscious than gynocentric men. They are aware of relationship pitfalls, may even be quite familiar with concepts like gynocentrism, hypergamy and male disposability.

It is their reaction to that information that may foment troubles. These men can be perpetually fulminating and overtly hostile to anything female. It’s the “all women are bitches and hoes” crowd, and the ever present resentments they carry can cause emotional and psychological atrophy. They may have a diminished capacity for reason and defensively take refuge in an ideology that shields them from examining their anger productively.

Another manifestation of the gynocentric reactive man is one who hides inside emotional armor, simply reducing women to their sexual utility, doing their best to get sex then get out. Unfortunately, it is a form of self-protection that may well heighten risk with repeated sexual contact with women who have not been assessed for anything other than physical attraction.

Finally, there are still other gynocentric reactive men who are just frustrated by the realities of lived experience with women. They find themselves caught in a web of confusion and consternation. They tend to be understandably mistrustful of women, and sometimes vacillate between being indifferent to them and being attracted. They feel stuck and outgunned. Chronic loneliness is often part of their lot. For this reason, many of them may be attracted to the other forms of reaction-based mindsets that don’t leave them feeling so vulnerable.

Gynocentric Reactive men get call misogynists a lot. They’re not. Setting aside judgements about the efficacy of their state of being, they are just men rationally demonstrating the will to self-protect. Regardless of how tiring the perpetual anger may be, they are much more functional and conscious than the gynocentrist.

The Gynocentric Proactive man routinely operates consciously with women. He has a clearly identified, personally chosen set of values that trump his sexual instincts and significantly temper his need for female approval.

Whether he includes women in his life or not, he is not burdened by fear of, or resentment toward, them.

He does not tolerate abuse, doesn’t take unnecessary financial risks or commit thoughtlessly. He can be available for a relationship if he chooses. He is also willing and able to let a relationship go that threatens his well-being. And he can do it without undue emotional distress.

Importantly, he is willing, indeed insistent, on evaluating any woman on his radar for risk and maintenance concerns.

It is important to reiterate here that none of these states of being can be called wrong. They are simply ways of coping in the modern sexual milieu. Even the gynocentric male is trying to cope in his way.

I will point out, however, that when I see men belittling and shaming other men for not walking in lockstep with them, it usually comes from gynocentric and gynocentric reactive men. Those are also the two states of being where, exceptions notwithstanding, I have observed the least happiness and the least reasonable points of view.

So, obviously, the intent here is to suggest that there is much more benefit to men in a Gynocentric Proactive state of being. The benefits are certainly there for emotional health.

Courtly Love as Religious Dissent – by Jeffrey B. Russell (1965)

Love in the Song of Songs

In the lead up to Valentine’s Day when Christian (and other) women look forward to receiving romantic love overtures from men. So I thought I would ask AI to clarify what is the nature of love as portrayed in the most famous lovers book in the Bible.

Question: “What is the Hebrew word used for the kind of love portrayed in the Song Of Solomon?”

ANSWER: The primary Hebrew word for love in the context of the Song of Solomon is ‘ahabah’. Although it does not explicitly refer to romantic love or sexual desire, within the context of this love song, it conveys deep affection, longing, and desire.

Even in the Septuagint, which includes a Greek translation of the Song of Songs, the word used is agape, though clearly the term eros is also applicable to the descriptions of longing and desire that take place between the two lovers.

Ahabah, agape and eros described in Songs are examples of reciprocal love, unlike the unidirectional, medieval practice of romantic love which requires sycophantic male love service toward pedestalised women. With these distinctions in mind, we can say that Christians who wish to celebrate romantic love, whether on Valentine’s or any other day, can be justifiably be charged with practicing heretical versions of love.

As a second note of clarification, St. Valentine had nothing to do with the concept of romantic love during his life, nor did romantic love play a part in the early legends that surrounded him. His namesake only later became associated with courtly & romantic love through a fanciful revisionism in the Middle Ages via poets like Chaucer who fabricated a link between the saint and romantic love. That conflation was continued by William Shakespeare, John Donne and many other poets, leading to the popular conception of romantic chivalry we inherit in today’s Valentine’s celebration.

Romantic love & cuckoldry of husbands

The invention of romantic chivalry/love in the Middle Ages taught women to view extra-marital love as more rewarding than their marriages, giving the first signs of attack on husbands and marriage that would culminate in cuckolding, frivolous marriages and the removal of fault-based divorce.

The cuckolding is showcased in famous tales of romantic chivalry: Tristan and Iseult, Lancelot and Guinevere, and in the lives of real men and women from that period forward: ie. Romantic interests trump marriage.

Enter OnlyFans wives.

Note (below) the appalling situation that husbands were originally placed in, leading modern husbands to accede to women’s romantic interests. Tradcons today continue to make noise about the importance of romantic “date nights” which are attempts to make their marriages romantically titillating in the assessment of wives.

Below is an excerpt from Valency’s In Praise of Love: An Introduction to the Love-Poetry of the Renaissance (1958):

Source: Maurice Valency, In Praise of Love: An Introduction to the Love-Poetry of the Renaissance (1958)