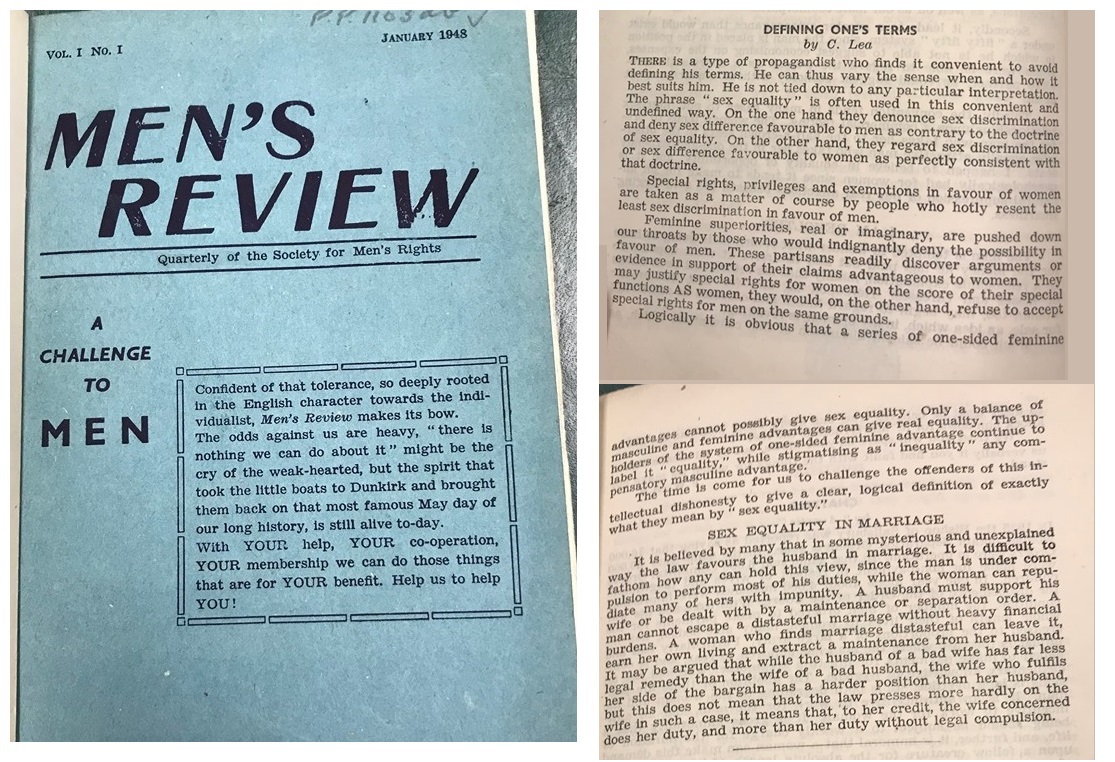

Defining One’s Terms

by C. Lea

THERE is a type of propagandist who finds it convenient to avoid defining his terms. He can thus vary the sense when and how it best suits him. He is not tied down to any particular interpretation.

The phrase “sex equality” is often used in this convenient and undefined way. On the one hand they denounce sex discrimination and deny sex difference favourable to men as contrary to the doctrine of sex equality. On the other hand, they regard sex discrimination or sex difference favourable to women as perfectly consistent with that doctrine.

Special rights, privileges and exemptions in favour of women are taken as a matter of course by people who hotly resent the least sex discrimination in favour of men.

Feminine superiorities, real or imaginary, are pushed down our throats by those who would indignantly deny the possibility in favour of men. These partisans readily discover arguments or evidence in support of their claims advantageous to women. They may justify special rights for women on the score of their special functions AS women, however they would, on the other hand, refuse to accept special rights for men on the same grounds.

Logically it is obvious that a series of one-sided feminine advantages cannot possibly give sex equality. Only a balance of masculine and feminine advantages can give real equality. The upholders of the system of one-sided feminine advantage continue to label it “equality,” while stigmatising as “inequality” any compensatory masculine advantage.

The time is come for us to challenge the offenders of this intellectual dishonesty to give clear, logical definition of exactly what they mean by “sex equality.”

SEX EQUALITY IN MARRIAGE

It is believed by many that in some mysterious and unexplained way the law favours the husband in marriage. It is difficult to fathom how anyone can have this view, since the man is under compulsion to perform most of his duties, while the woman can repudiate many of hers with impunity.

A husband must support his wife or be dealt with by a maintenance or separation order. A man cannot escape a distasteful marriage without heavy financial burdens. A woman who finds marriage distasteful can leave it, earn her own living and extract a maintenance from her husband.

It may be argued that while the husband of a bad wife has far less legal remedy than the wife of a bad husband, the wife who fulfils her side of the bargain has a harder position than her husband, but this does not mean that the law presses more hardy on the wife in such a case, it means that, to her credit, the wife concerned does her duty, and more than her duty without legal compulsion.