Author: rtbavfm

The Aeneid and the horrors of a blue pill existence

By Jai Singh

Virgil’s epic poem the Aeneid tells the story of Aeneas and his people, the Trojans, as they flee from their destroyed home of Troy (the Trojan War is recounted in Homer’s Iliad) and venture to Italy to build a new home; the descendants of Aeneas himself (Romulus and Remus) are destined to become the founders of Rome. The first half of the poem recounts the Trojans’ journey to Italy, while the second half recounts the war that breaks out between the Trojans and the Italians, a war kicked off thanks to petty divine intervention by Juno, wife of Jupiter and queen of the gods.

The character arc of Aeneas – the protagonist of the poem who is, “famous for his piety,” (page 3) – provides an arguably excellent example of what occurs as a result of living a blue pill life as a man. We should begin by noting the importance of Aeneas’, “piety,” as it is his defining characteristic and one of the four virtues inscribed on the shield of Augustus (the first Roman emperor and the one during whose reign Virgil wrote the poem); the Latin term for this is pietas, which refers not only to religious devotion, but also to loyalty to one’s family and one’s compatriots and thus selflessness.

The enforced adherence to pietas occurs in a manner that is reminiscent of the blue pill existence by demanding numerous sacrifices from Aeneas in the service of a seemingly noble yet distant and nebulous ideal. In Book II of the Aeneid, Aeneas tells the story of the fall of Troy, which resulted in the death of his wife, Creusa. While Aeneas is running through the burning city, trying to find her – he lost track of her while initially escaping – he encounters her ghost, who tells him that her death would not have happened, “without the approval of the gods,” (as a ghost, she has been to the underworld and can thus see the future) also instructing him to wipe, “away the tears you are shedding for Creusa whom you loved,” (page 47) because they will change nothing. Aeneas notes that he was left, “there in tears and longing to reply,” to her and yet was unable to do so.

The loss of Creusa is arguably the first major sacrifice demanded by the gods – specifically, as Creusa notes, it is the, “Great Mother of the Gods,” (page 47) referring to Juno – from Aeneas, and yet it is a sacrifice made without consent (it occurs because destiny has it that Aeneas will marry another woman named Lavinia, with whom he will give birth to the ancestors of Romulus and Remus). Aeneas is simply forced to accept this tragedy, and its justification is that it serves a higher purpose; even though Aeneas is committed to serving said higher purpose, the death of his wife still takes an understandable toll on him.

The second major sacrifice demanded of him is the severing of his relationship with Dido, the queen of Carthage, in Book IV. Aeneas and Dido fall in love after the Trojans land in Carthage – and have sex for the first time thanks to cynical divine intervention from Juno – but Jupiter (king of the gods) sends his messenger Mercury down to order Aeneas to leave Dido and resume his journey to Italy.

Jupiter questions – in an arguably paternalistic fashion, as if he knows what is better for Aeneas than Aeneas himself – whether, “the glory of such a destiny [becoming a venerated figure in Roman legend] does not fire his heart.” (page 76) When Dido eventually catches Aeneas trying to leave Carthage secretly, Aeneas makes this juxtaposition between what he desires and what the gods demand of him explicit when he states that, “It is not by my own will that I search for Italy.” (page 79) West, the translator, points out in the introduction that the, “weakness and misery,” that Aeneas shows upon being confronted by Dido are signs of, “Virgil’s human understanding,” (page xix) and a contribution to the contrast between the humanity of those on the ground and the wilful apathy of those above.

It is arguably the case that blue pill men live a life characterised by an internal conflict between what they consider to be their duty to the blue pill world around them and the women in their lives on one side, and their own personal desires on the other. Such a life involves the subjugation of the latter to the former in the name of being a ‘good man‘ or a ‘male ally‘, ideals of masculinity which we red pill men know are meaningless. The one distinction I would draw between the average blue pill man and Aeneas, however, is that this process involves more consent from the blue pill man than it does from Aeneas; such men must fully submit to the loss of their individuality and make the necessary sacrifices to do so, while Aeneas genuinely has far less control over this process.

We must also analyse the conclusion of the Aeneid to get a picture of the final destination to which blue pill thinking inevitably leads men. In the final lines of Book XII, Aeneas slays Turnus, prince of the Rutulians (one of the Italian tribes that are at war with the Trojans), the justification for which has been debated by many scholars. The killing of Turnus is certainly at odds with pietas (it has nothing to do with devotion to either the gods or anybody), and it goes directly against another one of the aforementioned four virtues – clementia, which means ‘mercy’ (it’s where we get the word ‘clemency’ from). By the time that Aeneas kills him, Turnus is lying on the ground and begging for mercy, after Aeneas’ spear strikes him in, “the middle of the thigh,” (page 290) and cripples him; Turnus also has his strength sapped from his body thanks to divine intervention from Jupiter, ensuring that he had no chance of winning the duel.

Virgil applies the adjective furiis to Aeneas’ emotional state as he is about to kill Turnus, an adjective that is related to the Latin term furor, which can mean ‘frenzy’ or ‘rage’ or ‘madness’. Furor is significant in that it is depicted as being the opposite of pietas, Aeneas’ defining characteristic; furor connotes letting one’s emotions control one’s actions (instead of one’s devotion to the gods or to others) and being excessively (or, as the Romans would argue, immorally) selfish, being at odds with the selflessness associated with pietas. Aeneas adopting the characteristic of furor is like Jesus succumbing to the temptations of Satan, or Michael Kimmel starting to respect men; it’s completely against his nature. So why does he do it?

My argument as to why Aeneas disregards the ethical code outlined on the shield of Augustus is because he sees no value in adhering to it by the end of the poem. Fulfilling his destiny is a task that has involved many sacrifices for him – namely the deaths of Creusa, Dido, his father Anchises (Book III), and the loyal son Pallas of his ally King Evander (Book X), all losses over which Aeneas grieves humanely – and yet Aeneas has not been justly compensated for these sacrifices, as his understandable human troubles have been ignored and only viewed as obstacles by Jupiter to the accomplishment of this goal. The promise of glory does not fully satisfy Aeneas – this is the type of promise, by the way, that contributes to the male disposability that characterises wars – and it is entirely understandable as to why.

The killing of Turnus lacks a clear moral justification because Aeneas does not believe that one is necessary when those who have been forcing him to abide by that code evidently do not care at all for his wellbeing. This killing is like the existential implosion of a man who has just realised the shallowness of his own value structure, carried out with a nihilistic and Cain-esque fury reminiscent of men who murder their wives over unjust divorces. It is no wonder that such is the case, given that the structure of the idea of fate/destiny – where there is a predetermined end at which one will arrive, by whatever means necessary – resembles that of a lie (because when you lie, you choose an end ahead of time at which you want to arrive, and manipulate everyone and everything around you as much as is necessary to get there).

By the end of the poem, Aeneas has little to nothing of value to call his own, and so he curses Jupiter and destiny – or, in other words, the world around him – for stealing from him what he once loved, and the loss of faith in the proposition that existence is worthwhile is almost always accompanied by undeserved and futile (in the sense that existence can never be destroyed by acts of revenge committed against it) death.

The core lesson that we red pill men can learn from the Aeneid, brilliantly written as it was by Virgil, is that the subjugation of our will to external moral obligations that society expects us to adopt unquestioningly only contributes to the, “modern genocide on the male soul,” that Paul Elam describes in his video ‘Servant, Slave and Scapegoat‘ as being mercilessly conducted by the blue pill world. No matter what the dictates of those whom men perceive to be their gods may be, you must understand that your will is your own and that it can only be broken with your consent.

_____________________

Note: All page references to the Aeneid are to the Penguin Classics edition, translated by David West.

Daddy’s Little Nightmare

By Paul Elam

I’ve had many, many conversations over the years with blue pill men about red pill ideas. Interestingly, most of the men I’ve talked to have been pretty open to what I was talking about. At least in general terms my observations about men, women and the behavior typical to both resonated with them. I’ve routinely found men nodding agreeably as I described some of their not-so-positive experiences with women in relationship life. They did so even as some of them instinctively glanced over their shoulder, as if to make sure no one was seeing them agree with me.

Plenty of them even quietly acceded to my calling them out on their tendency to tolerate abuse, to enable and play white knight in order to stay out of the dog house. A life spent in some measure of frustration, trying to placate an errant child, of jumping through hoops to keep an uneasy peace is common to a lot of men. Sure, some men don’t share this experience. And some men claim they don’t. You can hear them bragging about how they are in charge of relationships when the woman isn’t listening. But most men I have talked to in relationships identify with this to one degree or another.

Most of them can chuckle at themselves a little bit when they talk about how they put up with the childish demands and entitled attitudes of their female counterparts. Some of them, without compunction, even cast themselves metaphorically as powerless little schoolboys, fearful of being sent to the principle’s office, represented by the disapproval of their wives or girlfriends. They do this with no sense of embarrassment, as though they think all men live this way. And of course, there are plenty of men who do.

All this introspective honesty, this good-natured self-disclosure, takes a nosedive, however, when I’ve talked to men as fathers, vs just husbands or boyfriends. In that matter things become, shall we say, pricklier.

You see, it is pretty easy for a man to admit that petulant childishness is the default setting for a whole lot of women once they settle into a relationship. Most men will just nod their heads knowingly and shrug it off because in their minds, that’s just the way women are.

It’s quite another matter when you start to talk about the role of fathers in instilling said petulance and childishness; when you acknowledge that “Daddy’s little girl,” is highly prone to grow up (or just get older) and become “Daddy’s little bitch,” or much worse.

It’s quite ironic, listening to a man complain about how his wife has crazy unreal expectations. He bemoans the fact that she cannot be satisfied, no matter what he does. He claims that he pulls his hair out trying to figure out how to satisfy her endless demands only to be met with more disapproval and, of course, more demands. He wonders aloud how she ever learned to be such a bottomless pit, and such a bitch about it.

Then you go watch him interact with his four-year old daughter, whom he will endlessly coddle and for whom he will go to any measure to make sure she never lacks anything, no matter how trivial.

And it doesn’t stop when she turns five. Or fifteen, or twenty-five. When it comes to turning human females into paragons of pissy entitlement, the western father has few rivals.

I remember well former vice-president Joe Biden talking about being routinely physically abused by his older sister, informing the world that his parents would have “gone nuclear” if he had ever defended himself. That was the family rules, and they were not negotiable. The girl got to inflict physical pain on the other children with impunity. The boys got to take it. As Biden recounted, he “had the bruises to prove it.”

My clinical experience informs me that the Bidens weren’t by any means the only family who operated on the premise that assault was permissible by girls, and self-defense by boys was strictly verboten.

Often, the main enforcer of this lopsided affair is the alleged family patriarch. Along with the idea of bodily autonomy for the girl only is often a whole slew of double standards reflecting the fact that Daddy’s little girl has Daddy wrapped around her little finger.

After all, has anyone ever coined a phrase describing how a son has a parent wrapped around his little finger? Of course not, because it largely doesn’t happen. The closest thing you’ll ever hear to that is the term “Mama’s Boy” which is an entirely different story.

A “Mama’s Boy,” which implies blind service to the mother, is a pejorative pointing to the general weakness of the son and the power of the mother. Having Daddy wrapped around your little finger implies just the opposite. It is the raw sexual power of the female, and the powerlessness of the father, even with daughter in the state of childhood. She can just crawl into Daddy’s lap, wrap her little arms around his neck and get her way, every time. He just melts. I will spare us all an analysis of the Freudian implications of that little scenario. It’s too gross to go into. Suffice it to say that both family scenarios involve females with power and males without it.

Fathers, in this regard, generally don’t take well to a discussion of the subject. I’ve talked to several of them about enabling dads who treat their little girls like princesses, effectively turning them into cunts who are destined to make a succession of men completely miserable, and who will, in the end, be miserable themselves. Nobody can hold on to any kind of happiness when chronic, insanely unrealistic expectations are the expected path to get there. That’s the curse of modern womanhood. It’s why so many of them are miserable, and why they feel justified in making others miserable when their plans fall apart.

Now, at some point in the conversations with a handful of these fathers, they seemed to reach a snapping point. “Wait a minute,” they’d say, in a suddenly serious and demanding tone, “You’re not talking about me and my daughter, are you?” They weren’t kidding.

“Why not at all,” I lied, aware that we were getting into dangerous territory.

Here I was talking to guys who were so not enabling or over-protective of or unreasonable about their daughters that they looked to be willing to go fisticuffs with a 6’8” 280-pound man if he got too close to the truth.

Either that, or they were reacting chivalrously to an imagined slight against their little princess. I’ll let you decide.

There is a great deal that goes into creating a society of women who feel so entitled to unrealistic demands of men that they make themselves and everyone else suffer.

Certainly, as I mentioned earlier, feminism has played a huge role. So, have obsequious, spineless men. The kind who never met a woman they wouldn’t bend over backwards to please. There’s also basic biology. Men are driven to scatter seeds and the greatest majority of them want and need women’s permission and approval to do it. That alone has them urging women toward very unrealistic expectations in the long term. Very few men can maintain the lengths they go through to achieve sexual conquest. We hear women complain about that all the time.

Indeed, as we look at all this from the aerial view, we see that men in one form or another, are the main culprits. It’s entirely arguable that feminists are only demanding of men what they know men will ultimately give them, reasonable or not. So, in that light, the sole enablers of all this nonsense are men.

That includes fathers.

Fathers are the first arena where women learn their expectations of men. Fathers are the gateway to hypergamy and gynocentrism. They are women’s first lessons in all-take no-give relationships, and where they begin to learn the sheer awesomeness of their sexual power.

Consider that the next time you see a father walking hand in hand with a little girl wearing a tiara and a t-shirt with the word “Princess” written in glitter across the front. Think of it when you hear a teenage girl gush about all the things her Daddy buys for her, or when you hear a father boast that “nothing’s too good for my little girl,” when they would not dream of saying the same about their sons.

Think about it a little more when you see entire families enable abusive girls; when their relational and other forms of aggression are allowed to flourish at the expense of everyone else, particularly the boys.

And if you ever wonder why corrupt, disingenuous ideologies of privilege, like feminism, are so warmly received by a generation of females who think entitlement is the natural order of things, then take a deeper look at how they got there.

If you are looking clearly, you’ll see that chivalrous fathers are a big part of the problem. They shape the training ground for feminists and narcissists. And they will indeed get angry, possibly violent, when you call them out on it.

So, in most cases, it’s better to just let it be. There’s nothing to be gain by standing between Daddy and his Little Nightmare. Life will deliver its own consequences.

Who Was the First Feminist? | A Mythological Perspective

By Greta Aurora

Study: ‘Narcissism and perceived power in romantic relationships’

Joseph Campbell on ‘Romantic Love’ as a New Religious Mythology

JOSEPH CAMPBELL:

In all the great traditional representations of love as compassion, charity, or agape, the operation of the virtue is described as general and impersonal, transcending differences and even loyalties.

And against this higher, spiritual order of love there is set generally in opposition the lower, of lust, or, as it is so often called, “animal passion,” (eros) which is equally general and impersonal, transcending differences and even loyalties. Indeed, one could describe the latter most accurately, perhaps, simply as the zeal of the organs, male and female, for each other, and designate the writings of Sigmund Freud as the definitive modern text on the subject of such love.

However, in the European twelfth and early thirteenth centuries, in the poetry first of the troubadours of Provence, and then, with a new accent, of the Minnesingers, a way of experiencing love came to expression that was altogether different from either of those two as traditionally opposed. And since I regard this typical and exclusively European chapter of our subject as one of the most important mutations not only of human feeling, but also of the spiritual consciousness of our human race, I am going to dwell on it a little.

From Myths to Live By

Beyond belief: gender, science and ideology. Prof Eric Anderson

Eric Anderson is Professor of Sport, Masculinities & Sexualities, University of Winchester.

As scientists and rational human beings we like to think of our ourselves as people swayed by hard evidence. However there is another thread in the human experience, one which can sway us to have “faith” in ideas that go beyond science.

Revisioning Anima and Animus

The following book excerpt from Teaching Jung, Edited by Kelly Bulkeley and Clodagh Weldon, details a popular Jungian revisioning of Anima and Animus concepts.

‘ While merely scratching the surface of a rich Jungian literature of gender, we can see that the legacy of creativity approaching gender has been exceptionally fertile. Probably the most significant and far-reaching creative developer of Jung’s legacy is James Hillman, who in the 1970s produced two key articles radically transforming the anima. Through a critical rereading of Jung’s texts, Hillman aims to detach the anima from Jung’s delight in opposites. The anima is not limited to men. “She” should adopt Jung’s other name for her as “soul” and take her rightful place as a structure of consciousness in relationship to unconsciousness in both sexes . So the anima now fully inhabits her role as relatedness, as the bond to the unknown psyche, not to other people.

It follows that Eros be recognized as the separate function of sexuality and not falsely joined to the anima. Women no longer carry the anima or soul for men. They have their own anima-souls to cherish. Similarly, both sexes have equal access to animus or spirit.

Hillman then goes further to argue that anima as relatedness to the unconscious is the true basis of consciousness. Such a move dethrones the ego, which has been built upon the culture of the hero myth. “He” is driven by the desire to conquer and repress the other. Useful in the child and adolescent phases of life, the hero myth needs to be discarded by the adult who discovers his or her true being in anima-relatedness.

For Hillman, the anima is the archetype of psychology and soul making. She can manifest as singular or plural. Anima and animus ideally enact an inner marriage, marking the most fertile aspect of psychic development; they are the psychic lenses by which the “other” is known. So if the anima is seen as “one,” that is not to be taken as her essence. Rather, it is that she is regarded through a perspective conditioned to see “ones.” Hillman’s revisions of anima are exhilarating. They open up possibilities in ways that are faithful, I would venture, to Jung’s sublime intimations of gender as the point where reason and theory are defeated. ‘

[Teaching Jung – p. 175]

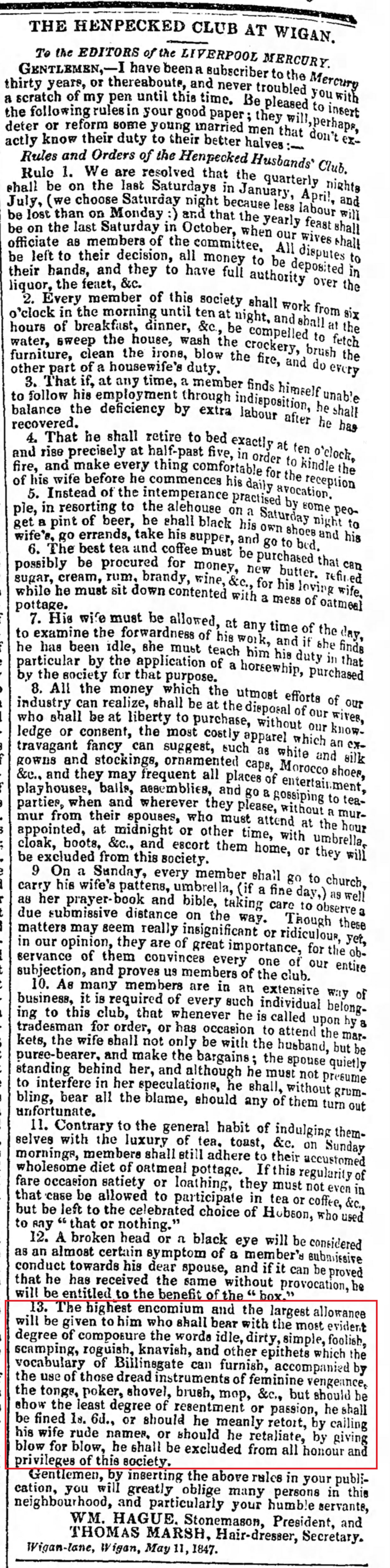

Advice for men in 1847, compliments of the ‘Henpecked Club’

The following article appeared in the Liverpool Mercury etc Tue Jun 15 – 1847

The Zeta Male

The following article appeared in the Nigerian publication Pulse.ng in 2017:

___________________________________________

A new class of men who don’t care what you think

There are three types of men….

The term alpha male shouldn’t be strange to you. It has become a pop culture buzz word up to the point of overuse. The alpha male is the confident, strong male who is the leader of the pack. Things revolve around him and he leads the way for others.

The alpha males are known as the bad guys, assholes or even Yoruba demons.

The beta male is the next on the pecking order. He is the opposite of the alpha male in the pack. He lacks charisma, charm, physical presence and confidence.

The beta males are the nice guys that are normally friend zoned by hot babes.

Last on the list is the omega male. He is at the bottom of the pile. He is socially awkward and doesn’t look presentable. In other words, he is a slob. Nobody wants to hang out with these type of guys.

Apart from these types of men, there is a new classification of men- the zeta male.

The three types of men are based on largely how women perceive them and society expectations. The zeta male is a rebel and doesn’t give a damn about women and society.

A zeta male is used for men who have rejected the traditional expectations associated with being a man- a provider, defender, and protector. He rejects stereotypes and doesn’t conform to traditional beliefs. He marches to the beat of his own drum and refuses to be seduced and shamed by anyone.

The term zeta male first appeared on the Internet in 2010. The appearance of the zeta male in the hierarchy of men has a lot more to do with what is known as Men Going Their Own Way.

Abbreviated as (M.G.T.O.W), this is a movement of men who have detached themselves from societal standards and expectations of women. According to Urban Dictionary M.G.T.O.W “is a statement of self-ownership, where the modern man preserves and protects his own sovereignty above all else. It is the manifestation of one word: “No”. Ejecting silly preconceptions and cultural definitions of what a “man” is.”

While an alpha female might find feminism amusing, the zeta male hates it. Zeta is named after Zeta Persei, the third-brightest star in the constellation.

According to website A Voice For Men “Persei is a variation of Perseus, the first of the Greek mythological heroes.” In Greek mythology, Persei slew Medusa. Medusa happens to be the symbol for feminism.

Zeta male is the fourth dimension of men. It will be interesting to see how long the zeta male will last in this era of social constructs.