By Diana Davison

A long time ago (15th century) in a land not too far away (France) a protofeminist named Christine de Pizan initiated a public debate later named La Querelle de la Rose. Simone de Beauvoir honours Pizan as the first woman to “take up her pen in defence of her sex”[1] but Christine was not fighting for new rights, she was strictly defending the chivalry-based gynocentric culture that she saw crumbling away before her eyes.

Though some feminists deny Christine’s status as a member of the gang, she did seem to have set the standard for how women change the public narrative; lies, elitism, deception and manipulation of history bordering on fraud.

Like all feminists who followed in her footprints, she set a Machiavellian example. The end justifies the means and, while you re-write “herstory”, make sure to claim you are meek and helpless the whole time.

But let us go back to the start of this adventure. We shall travel to c1275 when a man of some talent took up an incomplete poem called La Roman de La Rose and added a whopping 18,824 additional lines to the original 4,000 to create what would become one of the most widely read works of medieval times. Not only did the second author, Jean de Meun, create a cult following, his work was mimicked by Chaucer and Dante. Overall, a charmingly good chap for literary culture.

For over a hundred years this poem proliferated, was translated, adored, and revered as a work of genius. It outlined the troubles and challenges a youth may face when trying to woo a young lady in the world of chivalry. As in most good stories, the goal was not attained easily.

Presented in a dreamlike setting, our hero is guided by personified attributes such as Reason and Genius who help him to bypass all the lady’s defences and capture her “castle.” The language is considered quite risque for the times.

Around 1401 a gentleman named Jean de Montreuil, who served as secretary in the king’s chancery of France, was convinced to read the poem and wrote a glowing review which circulated about the land. It crossed the path of a woman named Christine de Pizan.

Christine was in a unique position compared to other women of her time. She had been raised in the court where her father, despite her mother’s disapproval, urged her to learn how to read and write. These skills came in handy after both her father and husband died quite young leaving Christine with debt and children. She was not overly pleased with her reduction of social status but managed to secure some work as a copyist instead of having to work at spinning or other demeaning trades.

She had begun by writing romantic poetry and secured some patrons who paid her for the work she sent them. She was a clever mimic and was able to write in whatever style her patrons preferred. She would likely have continued to meet survival needs as things were but decided, upon seeing Montreuil’s treatise, to take a chance and use her pen in defence of her desire to improve her career.

She had begun by writing romantic poetry and secured some patrons who paid her for the work she sent them. She was a clever mimic and was able to write in whatever style her patrons preferred. She would likely have continued to meet survival needs as things were but decided, upon seeing Montreuil’s treatise, to take a chance and use her pen in defence of her desire to improve her career.

Thus began an exchange of letters between Christine and defenders of the poem La Roman de La Rose.

These letters became public because Christine de Pizan decided to publish them. She was quite creative in her publishing by arranging them out of chronological order and removing the best arguments that her opponents had offered. Just like a feminist.

Some of the missing letters have since been recovered.

Christine’s main problem with the famous poem amounts to censorship. She takes exception to the naming of genitals and with advice being given as to how to trick women into having sex. Christine was a very conservative Christian. As such, you might think that she really did find the whole storyline repulsive if she hadn’t stated in a letter that the debate was “good-humored, an example of a difference of opinion between worthy persons”[2] and mentioned in another letter that a reply made her laugh.

The Romance of the Rose is rather bawdy and, at times, obscene: kind of like The Vagina Monologues.

Christine intitiated the debate by replying to a letter she acknowledged was not addressed to her. She bypassed that fact by publishing the letters out of order to make her “reply” look solicited.

She begins by stating that her opponents are very learned and that she is very ignorant, which she hopes will not taint their reading of her correspondence. She claims to be weak and timid. Of course, only timid people publish private letters and send copies of it to the Queen.

She begins by stating that her opponents are very learned and that she is very ignorant, which she hopes will not taint their reading of her correspondence. She claims to be weak and timid. Of course, only timid people publish private letters and send copies of it to the Queen.

Speaking of the Queen, who was one of Christine’s patrons, one of Pizan’s approaches was to link female virtue directly to Queen Isabeau of Bavaria “to the point at which the Queen becomes synonymous with virtue, Christine essentially lays the Queen under an obligation to accept her position; not to do so would be to reject her very self.”[3]

Nice trick.

Despite feminist claims that Christine tackled this monumental task alone, she was abetted by Jean Gerson, a long time family friend from her courtly days. Gerson was a strange bedfellow but he and Christine shared some religious ideals and were united both on the misogyny front and in speaking out about the “body politic” in other works. He’s not always mentioned in the discussions of the Querelle because feminists would like you to think Christine didn’t have a white knight helping her out.

The problem faced by both Pizan and Gerson was that de Meun’s poem was, and is, a work of art. When his characters speak they speak as that character would and do not represent the thinking of either the author or God. That is often the problem of censorship fanatics. The other big problem is that they have to admit they actually read the cursed thing.

When you read something distasteful, it is hard to blame anyone but yourself for the fact that you read it. If you didn’t read it or look at it, you can hardly have an opinion. Christine claims to have skim read over the worst of the worst but still approaches it as if she can fully assess the artistic merits of the work.

The accusations against her, which she deletes from her version of events, are that she is a novice who can’t comprehend advanced works and that she is speaking out of turn because she got a lot of recent praise and is suddenly full of her own ego:

“Yet what do we make of Pierre Col’s contention, suppressed by Christine, that her actions have resulted from her envy of ‘la tres elevee haultesse du liver’ [the very loftiness of the book], and that she had better be careful so as not to suffer the fate of the crow who, when ‘someone praised his song, began to sing louder than usual and let his mouthful fall.'”[4]

Christine responds with continued claims to humility and simplicity which, ironically and with calculation, guarantee her fame.

While feminists praise Pizan as a defender of women, only a third of what she wrote in the debate is devoted to perceptions of women. The majority of her complaint is pure Christian objection to obscenity.[5] The purpose of her diatribe can be discerned in the writings that followed, after winning the prestige to write full fledged books.

So what did she write next?

The iconic work in the list of some feminist “must read” resources is Christine de Pizan’s City of Ladies. This is the first book that she published after the Querelle which took up the cause of women.

The City of Ladies copies the format of previous male writers, like de Muen, who present a story in allegorical dream sequence. As a character in her own book Pizan is ordered by her ficitonal ladies of Reason, Rectitude, and Justice, to construct an city with her pen in which women can take shelter. Not all women, only “virtuous” women of her discernment. Christine doesn’t actually believe that all women are good and pure and worthy of men’s love, she just wants to build really solid walls behind which some women can hide so that they can continue to be treated as godly creatures while the other women burn in fucking hell. It was a form of alchemy: Burn off the undesirables.

“Only ladies who are of good reputation and worthy of praise will be admitted into this city. To those lacking in virtue, its gates will remain forever closed” [6]

Those whores are giving women a bad name. Slut-shaming Central.

The gates of Pizan’s City are locked tight to adulteresses, lustful women of any sort, and those who don’t uphold Christine’s religious ideals. She has built this city on the foundations of mythical women, appointed the Virgin Mary as queen (who she alludes to herself as representing), and predicts that her city of imaginary wonder will never fall. It can’t because it’s not real.

The gates of Pizan’s City are locked tight to adulteresses, lustful women of any sort, and those who don’t uphold Christine’s religious ideals. She has built this city on the foundations of mythical women, appointed the Virgin Mary as queen (who she alludes to herself as representing), and predicts that her city of imaginary wonder will never fall. It can’t because it’s not real.

If we had any doubt about Christine’s intentional trickery, we need look no further than the pages of this debut novel which, unlike the letters of the Querelle, are unmolested. She takes examples of awesome women from the Bible and pagan mythologies and leaves out all the bad parts of the stories so that they all look virtuous.

For example, Abraham’s wife, Sarah, becomes a woman who was so lusted after that King Pharaoh forcibly stole her from her husband. For those who actually read the bible, you’ll find out that Sarah and Abraham tricked Pharaoh by telling him they were siblings so that he might fall in love and give her many riches. When God punished Pharaoh for seducing a married woman Pharaoh was flabbergasted and gave them whatever they wanted just to get the fuck out of town. They pulled this trick twice. And it turns out they actually were brother and sister. God didn’t seem to care about that.

Christine laments that one of her heroines, Semaramis, married her son to avoid having to share her kingdom with another woman but excuses her because it wasn’t a law at the time that she shouldn’t do that. That Semaramis managed to defend her kingdom after the death of her husband was more important than the laws of nature. The laws of nature are somewhat mutable in Christine’s world, when it suits her purpose.

“As for those men who are slanderous by nature, it’s not surprising if they criticize women, given that they attack everyone indiscriminately. You can take it from me that any man who wilfully slanders the female sex does so because he has an evil mind, since he’s going against both reason and nature.” [7]

So it’s in man’s nature to go against nature? It’s not hard to argue against logic like that.

In the final reading, we are left to wonder what it is Christine was really trying to accomplish. Did she think women were strong, capable people or objects to be fawned over and worshipped like children or gods? Christine answers that upon seeing the perfect dream ladies of her vision who arrive to show her the path of truth:

“I didn’t know which of my senses was the more struck by what she said: whether it was my ears as I took in her stirring words, or my eyes as I admired her great beauty and dress, her noble bearing and face.” [8]

Christine! You misogynist!!

How dare you objectify these women with your gaze?

Christine’s “city” presents and shelters women as goddesses. Like Pygmalion, who was uninterested in real women, she sculpts the perfect female so that men can worship the illusion. Christine was a traditionalist attempting to uphold and entrench all the privileges enjoyed by her gender since chivalric love had been introduced.

As a pioneer of feminism, she taught those who followed that every female flaw which can’t be excused can be erased from herstory.

Sources:

1. Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, p105

2. Heather Bamford, Remember the giver(s): the creation of the Querelle and notions of sender and recipient in University of California, Berkeley, MS 109, 2009

3. ibid

4. David F. Hult, Words and Deeds: Jean de Meun’s “Romance of the Rose” and the Hermeneutics of Censorship, New Literary History, Vo. 28, No. 2, Medieval Studies (Spring, 1997)

5. Ibid

6. Christine de Pizan, City of Ladies, p11

7. ibid, p19-20

8. ibid, p9

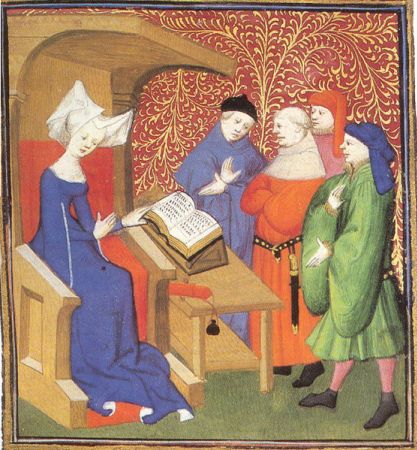

Editor’s note: feature image by Hans Splinter. –PW