Ruby Hamad’s recent Guardian article How white women use strategic tears to silence women of colour carries the byline “The legitimate grievances of brown and black women are no match for the accusations of a white damsel in distress.”

The article is interesting for a number of reasons, among them being that European ‘white woman feminism’ (WWF) is being called out for the farce that it is, and secondly those WoCs calling it out are reducing it to its knees.

While its true that women cry far more often and more easily than the average man – a biological fact examined by several research articles – there is no doubt that European white women have leveraged the crying game through the intricate culture of damseling that has made people hypersensitive to white women’s tears. An Arab woman cries? who cares. A black woman cries? meh. A white woman cries? – Quick call an ambulance!!

Hamad refers to this anomaly as the weaponising of white women’s tears, and adds;

As I look back over my adult life a pattern emerges. Often, when I have attempted to speak to or confront a white woman about something she has said or done that has impacted me adversely, I am met with tearful denials and indignant accusations that I am hurting her. My confidence diminished and second-guessing myself, I either flare up in frustration at not being heard (which only seems to prove her point) or I back down immediately, apologising and consoling the very person causing me harm.

It is not weakness or guilt that compels me to capitulate. Rather, as I recently wrote, it is the manufactured reputation Arabs have for being threatening and aggressive that follows us everywhere. In a society that routinely places imaginary “wide-eyed, angry and Middle Eastern” people at the scenes of violent crimes they did not commit, having a legitimate grievance is no match for the strategic tears of a white damsel in distress whose innocence is taken for granted.

Feminist women of every skin color share a belief in the existence of an oppressive patriarchy, female victimization at its hands, and the need to increase the power of women in every imaginable way. That mandate is enough to raise my resistance to each and every feminist pitch regardless of skin color – including by supposedly male-friendly feminists like Christina Hoff-Sommers and Camille Paglia who would institute a feminist utopia based on traditional male chivalry, their imagined golden era of the past that third wave feminists have supposedly undermined.

Added to those core beliefs, the cultural background of feminists often gives their behaviour a different accent or twist. I find myself agreeing with WoC feminists that white women have culture values embedded in their feminist project that render it, shall we say, different. This difference is why WWF has been accurately described as victim feminism, safe space feminism, and even fainting-couch feminism – a kind of battle between fragile maidens and those who would hurt them.

To be specific, white western feminists have their cultural roots in the European practices of damseling, chivalry and courtly love, practices that many WoC like Arabs, Asians and Africans do not. White Western feminists lean on European tropes to gain advantage over their WoC sisters, including the belief in (white) women’s moral superiority, extreme vulnerability and fragility, and the need for a protective chivalry that can be assumed or otherwise elicited with a few well-timed tears. The elements of the trope are used to foster an aristocrat-like status of white Western feminists, which is evidenced in their appeals to “dignity” “respect” “status” and “esteem” etc. – words usually reserved for dignitaries.

The cultural conventions that enable such behaviour closely resemble the sexual fetish of Subs to Doms, as seen in the European practice of a man going down on one knee to propose to a White Lady. That servile attitude has traditionally been expected of feminist WoC who have likewise been expected to go down on a metaphorical knee, so to speak, before their white women feminist betters. But WoC feminists are having none of it today – they are done with taking runner-up prize in the Oppression Olympics.

The fact that WoC want none of it is a death sentence for their own brand of feminism, for without the European customs mentioned above feminism simply cannot be; it absolutely requires damseling and a supportive culture of male chivalry in order to survive. That’s what has made WW feminism the one and only kind of feminism, ensuring its life and longevity, and without adopting elements of the European trope WoC feminism is dead in the water. At best WoC feminists could expect to get some platform for the simple act of attacking their well heeled and pedestalized sisters, but little more.

To be sure the dividing of WoC and WW feminisms is somewhat superficial, for despite their denials many WoC have already adopted some WW European practices, especially African American feminists, and wield them every bit as much as their ivory sisters.

Back to the question of crying, I believe the author has a mild case, if simply articulated, for the unique ways culture entwines itself with the tears of white Western feminists. That unique European brand has sometimes been referred to as ‘Anglosphere feminism’ – it is not something you will find in China, Iran or Sudan for example.

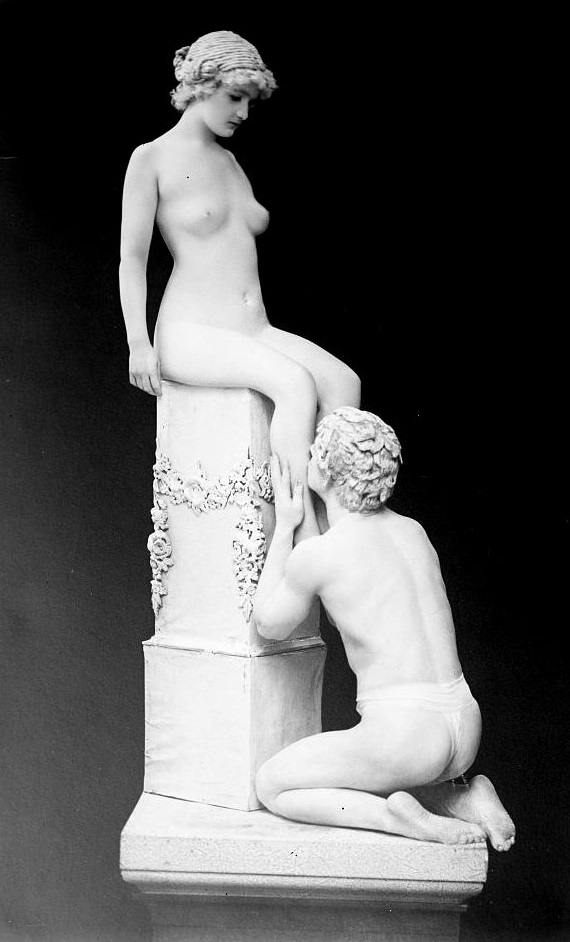

A feminist takes a well-earned break from being empathetic to men in pain.

White feminists have been busy drinking male tears for years, and they may find the prospect of WoC feminists drinking their tears somewhat disconcerting – and hopefully a reminder of just how badly they’ve been treating their menfolk. Judging by the current trajectory that’s exactly what will happen, or rather is happening – a callous disregard for white women and their issues by WoC. The result is that WW feminists are finding out their hands are tied in some of the same ways that men’s hands are tied based on the formula that perceived privilege = gag orders.

How do WW feminists and women feel to be in the same pit with white Western men? Will they take comfort from the usual ‘suck it up’ mantra reserved for Western males? Whatever their next moves its clear that European white women’s damseling and status-seeking has reached the teleological end of its evolution, called out by none other than women of color.

See also:

The Origins of Damseling

Two Modes of Damseling

The Near-Irresistible Lure of Damseling

Women of Color Feminists Vs. White Feminist Tears

Alison Phipps: White Men’s Ship Floats on White Women’s Tears

Damseling, Chivalry and Courtly Love In The Feminist Tradition

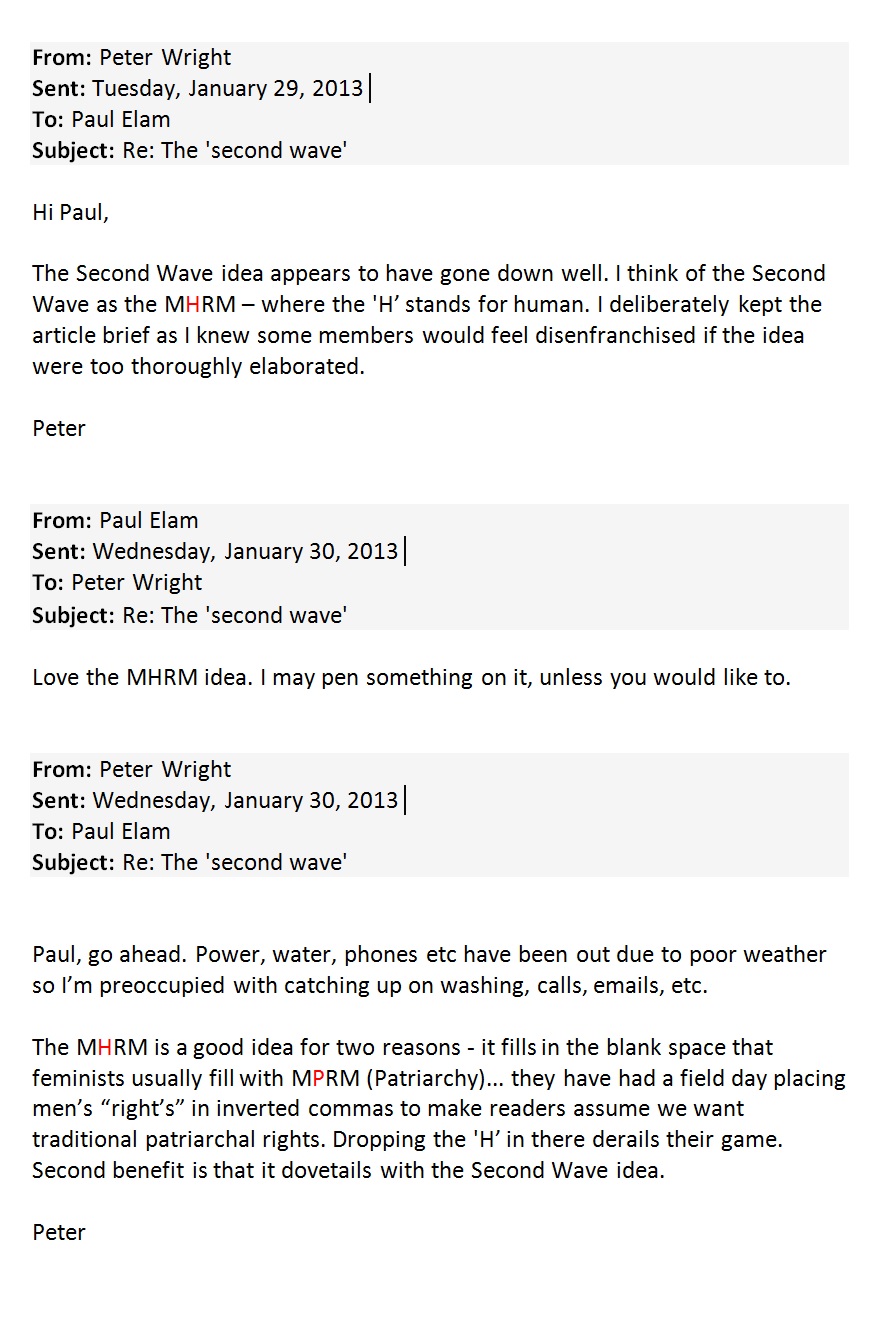

Following that email exchange, Paul Elam went ahead and wrote an article in which he made the following official announcement:

Following that email exchange, Paul Elam went ahead and wrote an article in which he made the following official announcement:

In a

In a