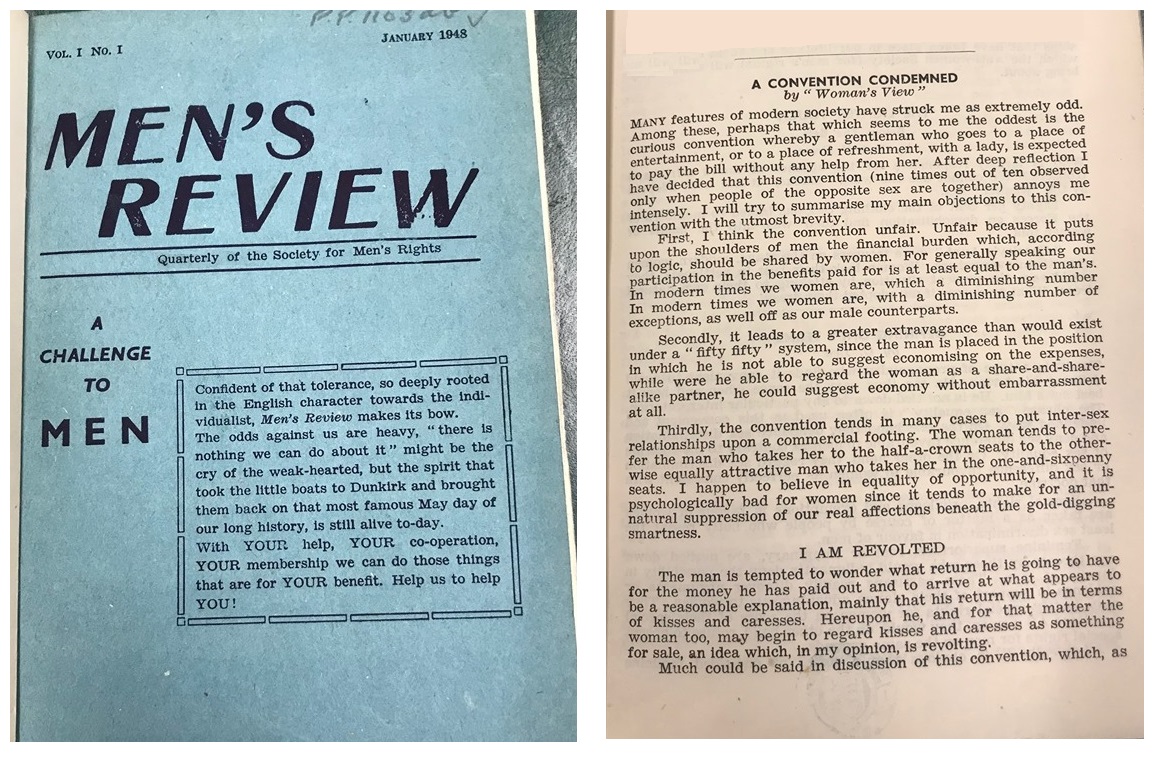

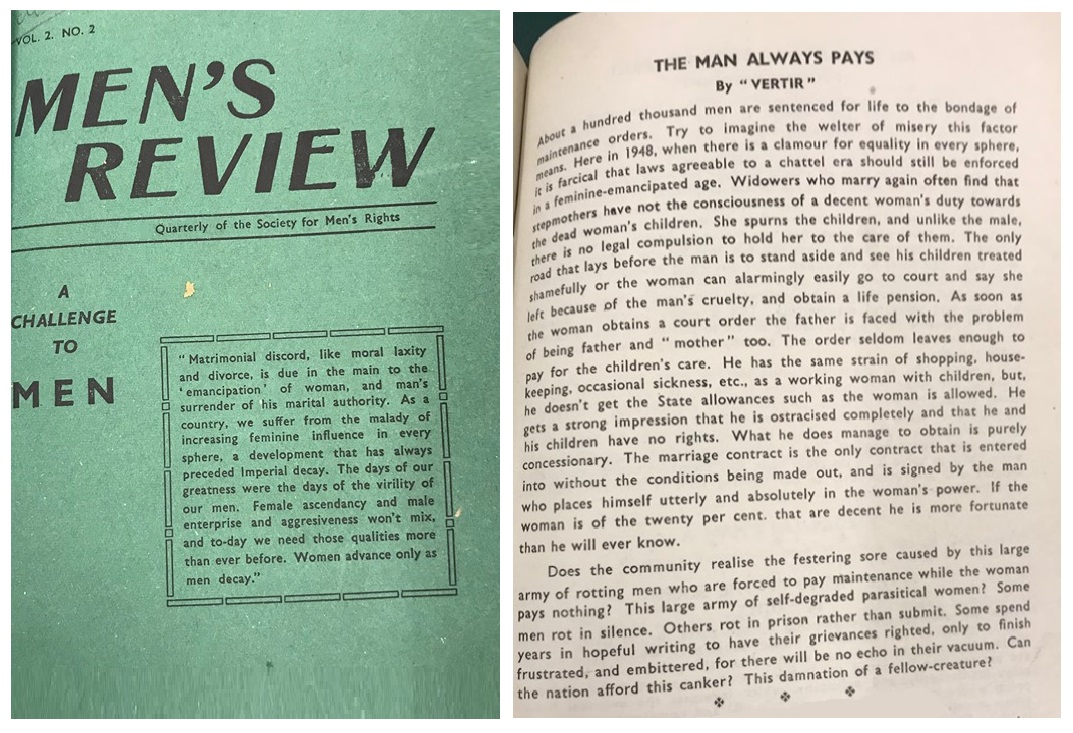

The following article appeared in the 1948 edition of the ‘Men’s Review’ – a pro men’s rights initiative that was active in Britain during the 1940s. – PW

* * *

A Convention Condemned

by “Woman’s View”

MANY features of modern society have struck me as extremely odd. Among these, perhaps that which seems to me the oddest is the curious convention whereby a gentleman who goes to a place of entertainment, or to a place of refreshment, with a lady, is expected to pay the bill without any help from her.

After deep reflection I have decided that this convention (nine out of ten observed only when people of the opposite sex are together) annoys me intensely. I will try to summarise my main objections to this convention with utmost brevity.

First, I think the convention unfair. Unfair because it puts upon the shoulders of men the financial burden which, according to logic, should be shared by women. For generally speaking our participation in the benefits paid for is at least equal to the man’s. In modern times we women are, with a diminishing number of exceptions, as well off as our male counterparts.

Secondly, it leads to a greater extravagance than would exist under a “fifty-fifty” system, since the man is placed in the position in which he is not able to suggest economising on the expenses, while where he able to regard the woman as a share-and-share-alike partner, he could suggest economy without embarrassment at all.

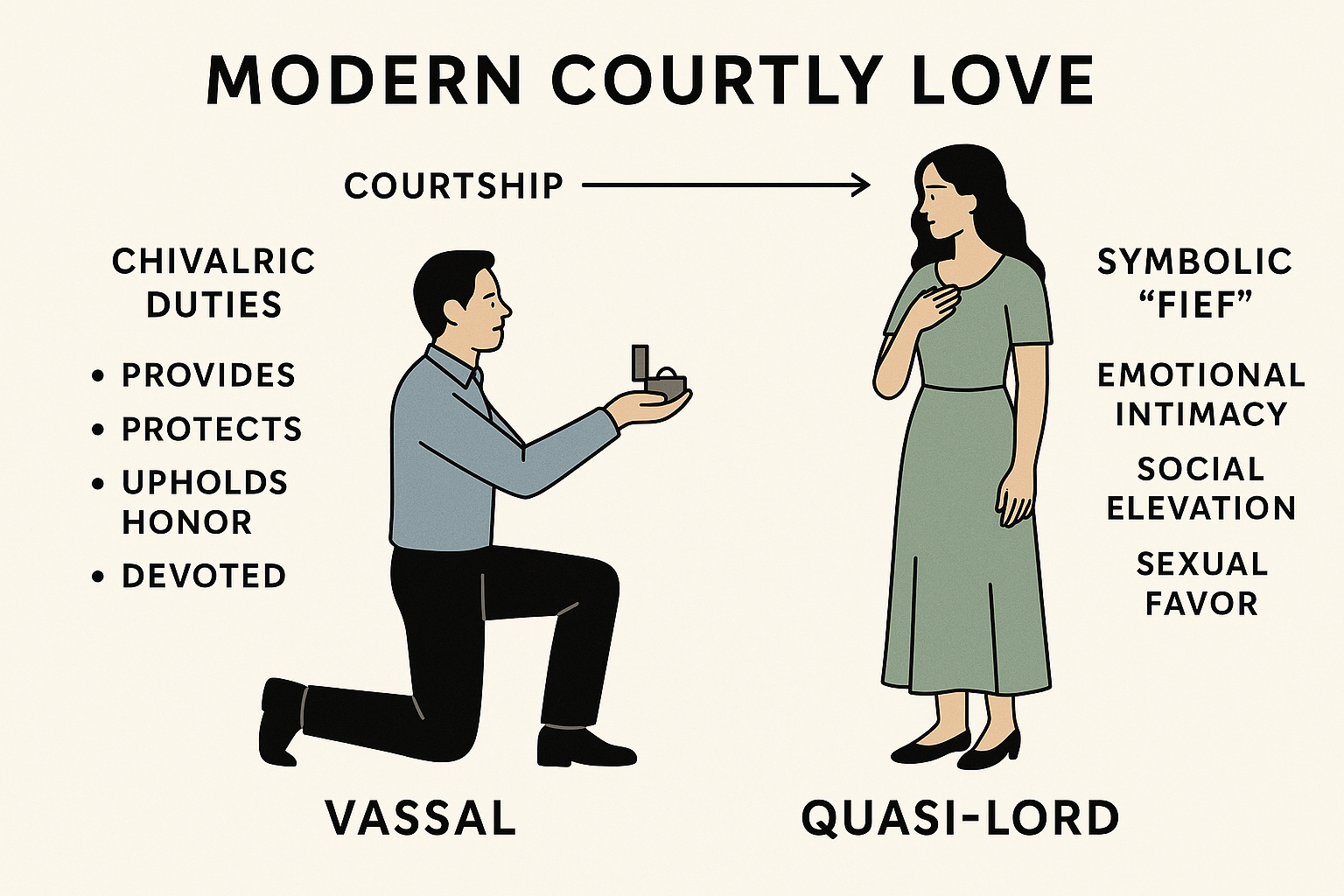

Thirdly, the convention tends in many cases to put inter-sex relationships upon a commercial footing. The woman tends to prefer the man who takes her to the half-a-crown seats to the otherwise equally attractive man who takes her in the one-and-sixpenny seats. I happen to believe in equality of opportunity, and it is psychologically bad for women since it tends to make for an unnatural suppression of our real affections beneath the gold-digging smartness.

I AM REVOLTED

The man is tempted to wonder what return he is going to have for the money he has paid out and to arrive at what appears to be a reasonable explanation, mainly that his return will be in terms of kisses and caresses. Hereupon he, and for that matter the woman too, may begin to regard kisses and caresses as something for sale, and idea which, in my opinion, is revolting.

Much could be said in discussion of this convention, which, as I hope to have shown, links up with our modern social outlook in an enormous number of ways.

The success of such an attempt would mean that we have changed the course of social history, and changed it, I believe, for the better. I do not deny that the thrill of this thought is as much of an inspiration as a mere desire to profit ourselves from the more convenient and fair system which I have advocated.

To those scoffers who say “You can’t change human nature,” “Every woman has her price,” or whatever expression you may use, I have only to point out the vast changes in inter-sex relationships that have taken place in our lifetime and those changes for which the Society (for men’s rights) will most surely bring about.