The following was printed in The Sun (Sydney, NSW), Sun 5 Nov, 1939.

Uncategorized

Gold Pill and the Modwife

By now many of you have seen the “Gold Pill” trending in the men’s issues sphere in social media. Naturally, wiki4men has the definition of the Gold Pill hot off the press:

The gold pill is a philosophy and practice defined by two motives:

1. Men expecting women to come to the relationship table with a material or economic commitment, and

2. Rejection of the unbalanced romantic model that favors passion over pragmatic concerns.

The Gold Pill is mentioned in a specific context within our sphere, namely, the history of marriage and relationship dynamics between men and women.

The dowry is highly referenced here, and the purpose of this is to remind those paying attention that historically speaking, the transactional element was very much intrinsic to marriage pairings. In other words, the pipedream touted by traditional gynocentrists today regarding male sacrifice and one-sided exaltation of the feminine was not the actuality of “traditional marriages” nor “traditional relationships”.

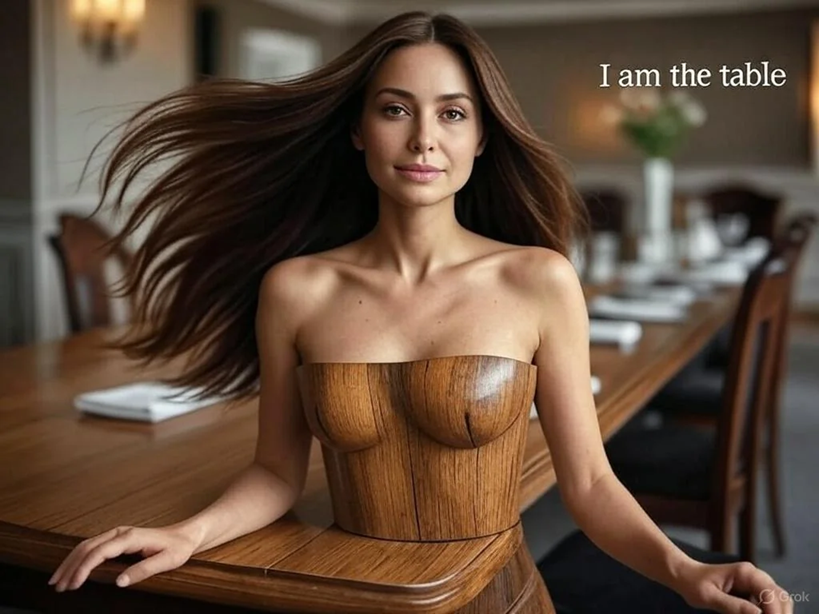

The historical existence of the dowry is case in point showing that women were expected to bring something to the table to help the arrangement start off in a stable way. To bring up the dowry today is as if holding a mirror to both traditional gynocentric women and the average feminism-inspired “independent woman” who comically imagines herself as “high-value”, and who claims that she is, in fact, the table.

Long story short, in their mind they don’t have to contribute a damn thing. We are told that they are financially independent and yet too economically underprivileged to be able to invest, simultaneously. Such is the paradox of the gynocentric world of women.

As such, the dowry can be utilized as a backdrop for getting through the idea that both sides actually contribute some material substance to the relationship, or to the marriage if that’s where things are. A far cry from being “superficial” and “materialistic” as those who parrot Romantic love ideology may decry this, such transactions are cornerstones to voluntary relations of any sort. Men asking, “What’s in it for me?” is not the inappropriate question that too many think it is.

As most of you know, when it comes to men’s issues I tend to highlight the case for men living according to his own terms and pursuing his visions in defiance of society’s expectations and demands (e.g. “You’re not a man if you don’t marry and have children and sacrifice all of your passions”). In other words, advocacy of MGTOW and Red Pill in its original, uncorrupted sense.

With this in mind I must confess that the history of marriage and its restrictive expectations has not been a serious interest in my case; with regards to that, I consider Paul Elam, Peter Wright, and the Gold Pill’s top proponent ThisIsShah to be the go-to sources on those. Hence, that is why I have been rather silent regarding the Gold Pill.

What’s more, what views I actively have on marriage, relationships, and sex itself can be accurately regarded as non-traditional in many cases, and I feared I didn’t have much to add to something that heavily references tradition in the way of the dowry, even if only as a historical backdrop and not a recommendation for its revival.

Then I got to thinking – we already have a paradigm for a relationship model that is both non-gynocentric and not exactly “traditional” either.

Remember the Modwife?

Let us recap. Wiki4Men defines the Modwife as follows:

A Modwife (noun), refers to women who have embraced multi-option lives over more traditional roles, and who accept or encourage multi-option lives for their male partners.

The article clarifies immediately that despite the use of the word “wife”, this can apply to non-legally-married relationships as well.

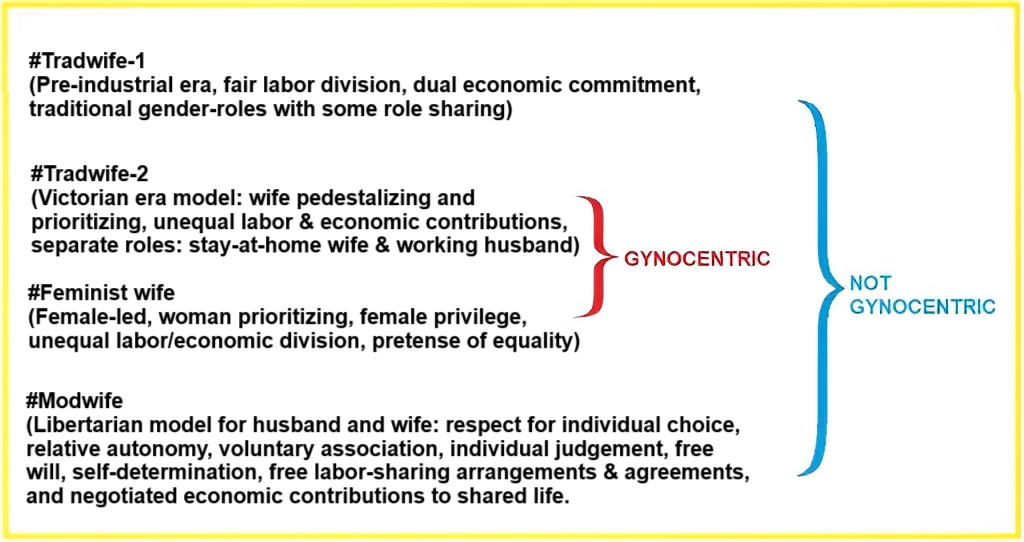

The following are the four relationship models for the reader to consider:

If you look at Tradwife-1, at this point we can easily associate phenomena such as the dowry as being slotted right into this arrangement. Through a Gold Pill lens, we can perhaps make some addendums: e.g. in addition to fair labor division, we can observe fair material contribution division; again the idea that both sides contribute something to the table. The contributions may not be identical in fact, but are fair in terms of the transaction.

Which is more that we can say for the gynocentric models in the middle. Observe – both insist that the woman “is the table.” Or if we wanted to take “pedestalize” literally, then the woman is the thing the man puts on top of the table in addition to all else he is expected to bring.

Finally, the Modwife model speaks for itself. It is tailor-made for our modern world; despite whines of tradcon influencers to “reject modernity”, not only can we not truly escape it as our society evolves technologically, but it behooves us to embrace it head on but with strong values.

Without being too tangential, if we don’t take ownership of modernity and let it reflect a manifestation of our better values, then it becomes left to the gynocentric, the entitlement-based, subjectivist, and the truly crazy.

Back to the Modwife. When we speak of the libertarian model for husband and wife, and everything else described in our model, what we are potentially looking at are a man and woman with their own agency, accountability, and not in the least their own means to bring something to the relationship. In our modern world, when we speak of a woman who brings something to the relationship, to the table if you will, it is a woman who is able to pull her own financial and material weight.

The often screeched bromides of the tradgyn are thus: a woman is inherently of value and a woman should not have to work. Despite their claim to be conservatives, note their opportunistic use of Marxist terminology as they deem that “wage slavery” is not what makes women happy – and should be left to men whom all that drudgery befits.

This is opposite of the Modwife model, in which the woman knows of herself as someone who has to work to live for their own standard of living just as the man does for his. Contributions are unironically a self-interest based framework because the man doesn’t devote his money “for her” per se, but for the relationship, and the family that would ensue if done right. As such, so shall a womans contributions be likewise.

What’s more, the Modwife paradigm would shatter tradgyns’ expectations of men as “wage slave” because in a one-sided gynocentric model, men’s work may turn to drudgery to fulfill the unrealistic expectation of their arrangement. The Modwife model hypothetically eases the burden on the man as the work contributions are fairly delineated via “making a proposal,” a phrase which traditionally referred to material negotiations from husband and wife over contributions to a shared life, only in this case the negotiating is done in a more libertarian spirit instead of following a fixed set of traditional customs.

As a matter of fact, the prior gynocentric bromides are also the opposite of the Tradwife-1 model. One just wants to shout at the tradcons dreaming their silly dreams about the housewife that doesn’t work – “Women worked back then too you blithering, blue-pilled simpish dolts!!” Women also worked in the trades, certainly they worked if they were part of an agrarian society, and in any case, the notion of the all-too-frail-and-precious, automatically-holy, automatically-superior, “fairer sex” is a myth to be discarded never too soon.

Gold Pill is for the Modern World

There is a saying I have seen in the Gold Pill discussion that I paraphrase as: “Whereas the Red Pill was a short-term and possibly imperfect solution, the Gold Pill is the long-term alternative for our modern world”. While I don’t necessarily agree that the Red Pill is short-term or imperfect, I agree with the implication that the Gold Pill has come into being for men (and women) to use as a new framework, and an alternative to the gynocentric idiocy of Romantic love. Moreover, we can see that mainstream “Red Pill” discourse tends to specialize in short term dating strategies, whereas the Gold Pill speaks more intelligently as a strategy for long-term relationships.

What makes a modern man, or a modern woman for that matter? One that exists in the now, where we live. Simple as that. Again, it’s folly to escape it; one must tackle it head on. In order for such men and women to do this, the right framework is necessary; what is the way for the modern man and woman to live their most accountable lives and have a rational, viable, and non-parasitic relationship and method to raise a family? That is the question that has to be asked and I think the Gold Pill is a very good distillation of that reality.

I bring this up because I wonder if some cannot see past the traditional historical backdrop of the dowry. I almost didn’t. Again however, I support the discussion because it is meant as an eye-opener to the idea that it is perfectly natural, and quite right, that both sides actually contribute something real and non-fantastical to the relationship.

The traditional dowry was a product of its time in which society perhaps didn’t resemble the relative freedoms and technological lucrativeness we do now, but then it seemed to have served to bring that material accountability to marriages. We can wholeheartedly derive example from this, even if what we ultimately end up with won’t necessarily resemble closely what the dowry did.

In finding a successor while “taking the Gold Pill”, might I suggest looking into the Modwife model! Think about it – investment in relationships no longer being one-sided like it’s been for too long. Actual accountability and agency across the board.

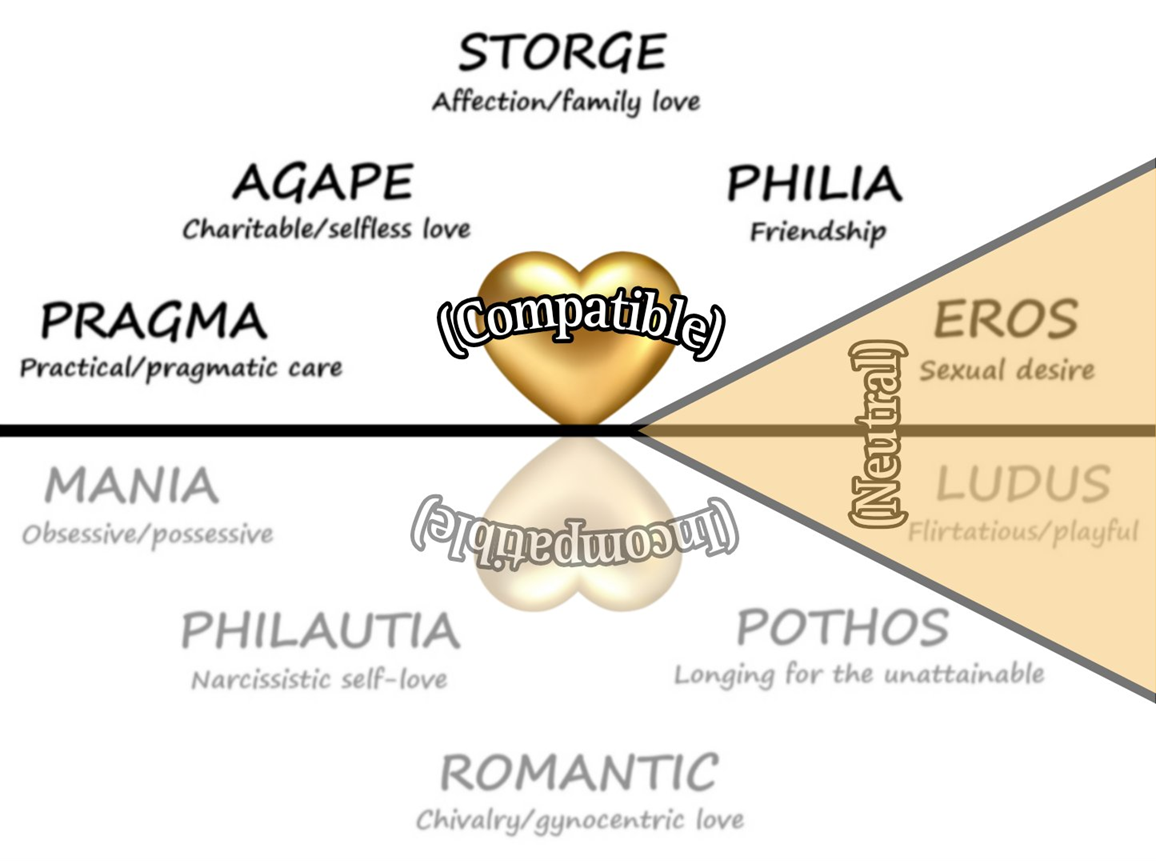

Pragma according to John Lee

John Alan Lee’s concept of Pragma love comes from his 1973 work Colours of Love, where he introduced the idea of six love styles. Pragma, one of the three secondary love styles, combines aspects of Ludus (playful love) and Storge (friendship-based love). It’s defined as practical, rational, and goal-oriented love.

Here’s how Lee described and structured Pragma:

Core Features of Pragma Love:

- Practical Compatibility Over Passion:

- Pragma lovers look for a partner who meets specific, often logical criteria—like shared interests, similar life goals, background, religion, or education.

- The focus isn’t primarily on emotional highs or physical passion but on whether the relationship makes sense and will function long-term.

- Deliberate and Thoughtful:

- This style involves cognitive filtering: people actively think through the qualities they want in a partner and evaluate potential mates accordingly.

- Love grows slowly, often starting from friendship, and deepens based on practical investment rather than overwhelming emotion.

- Long-Term Orientation:

- Pragma lovers often consider factors like financial stability, family approval, career alignment, and future planning.

- Romantic choices are shaped more by life goals and stability than by spontaneity.

- Low on Emotional Drama:

- Pragma avoids the turbulence of styles like Mania. It values emotional steadiness, commitment, and compatibility.

Examples Lee Might Offer:

- A person might think: “I want someone who wants children, shares my values, and has a stable career.”

- Love is not blind in this style—it is intentional and evaluative.

Lee’s Underlying Idea:

Lee saw Pragma as a practical response to the realities of love—in a world of increasing personal autonomy and social complexity, many people need more than romantic attraction. They need relationships that work, and they approach love like a partnership with practical criteria.

The Gold Pill According to Grok

The “Gold Pill” is an emerging concept in discussions about gender interactions and expectations, primarily within online communities focused on men’s rights and relationship dynamics. It presents itself as a philosophy that seeks to redefine modern relationships by emphasizing mutual respect, shared contributions, and a rejection of traditional romantic ideals that are seen as imbalanced or gynocentric. Below is an overview of the key points of this discussion based on recent sources:

Core Principles of the Gold Pill

-

Mutual Material and Financial Commitment:

-

The Gold Pill advocates for relationships where both partners bring tangible value to the table, including material or financial contributions, rather than one partner (typically the man) being expected to provide disproportionately. It challenges the notion that women should enter relationships with only emotional or presence-based contributions, pushing for equity in responsibilities.

-

This is framed as a response to perceived “gynocentrism,” where societal norms prioritize women’s needs or expectations, often placing men in roles of unreciprocated obligation (e.g., as providers or protectors).

-

-

Rejection of Romantic Idealism:

-

The philosophy rejects the “romantic model” of love, which it views as a culturally constructed narrative driven by media, advertising, and societal expectations. Instead, it promotes a broader understanding of love, drawing on ancient Greek concepts like:

-

Storge: Familial love, emphasizing long-term commitment.

-

Pragma: Practical love, focused on shared goals and compromise.

-

Philia: Deep friendship and mutual respect.

-

-

This shift aims to move away from dramatic, narcissistic romance that can set unrealistic expectations, leading to disappointment in relationships.

-

-

Equity and Clarity in Relationships:

-

The Gold Pill emphasizes clear agreements, mutual respect, and shared sacrifice in relationships. It encourages open communication and planning to ensure both partners are equally invested, avoiding “archaic assumptions” such as women expecting to be provided for without contributing or men being reduced to utilitarian roles.

-

It promotes the idea that “you are not the table; we build the table together,” symbolizing a partnership where both individuals contribute to creating a balanced relationship.

-

-

Countering Hypergamy and Gynocentrism:

-

The philosophy critiques hypergamy (the tendency for individuals, often women, to seek partners of higher status) and gynocentrism (a perceived cultural bias favoring women). It argues that men should expect women to have “skin in the game” by contributing materially and emotionally, ensuring fairness and mutual accountability.

-

This aligns with sentiments from figures like Peter Wright and Paul Elam, who argue that men are often treated as utilities in relationships without recognition of their emotional or nurturing roles.

-

Context and Emergence

-

Origins: The Gold Pill was notably introduced around May 2025, with discussions amplified through platforms like YouTube and Twitch. For instance, ThisIsShah launched the concept on his YouTube channel on May 10, 2025, and it gained traction through a Twitch livestream hosted by Coach Greg Adams on May 14, 2025.

-

Relation to Other Ideologies:

-

The Gold Pill positions itself as distinct from the “Red Pill” (which focuses on perceived harsh truths about gender dynamics and often leans toward anti-feminism) and traditional conservatism (which may advocate for rigid gender roles). It rejects the nihilism of the Red Pill and the dogma of traditionalism, aiming for a balanced, pragmatic approach.

-

Unlike the Red Pill, which has been criticized for misogyny and extremism, the Gold Pill seeks to avoid misogyny or martyrdom, offering a linguistic framework (e.g., terms like “provision without reciprocity” or “unpaid dowry”) to discuss imbalances without vilifying any group.

-

-

Cultural Critique: The Gold Pill critiques modern relationship dynamics, arguing that societal expectations often place unfair burdens on men while undervaluing their contributions beyond financial provision. It also challenges women to move beyond traditional expectations of being provided for, advocating for a rebalanced “social contract.”

Broader Implications

-

Parenting and Nurturing: The Gold Pill highlights the evolving role of fathers, challenging the outdated notion that parenting value lies solely with mothers, advocating for recognition of men’s emotional and practical contributions.

-

Linguistic Tools: The philosophy introduces terms like “gynocentrism” and “provision without reciprocity” to articulate perceived imbalances in relationships and society, aiming to foster discussion without resorting to hostility.

-

Harmonious Relationships: Posts on X suggest the Gold Pill seeks “harmonious relationships” in an era of perceived rampant misandry, encouraging men to negotiate relationships with clear expectations and mutual benefits.

Recent Discussions and Sentiment

-

The Gold Pill has sparked conversation on platforms like X, with users framing it as a way to break stereotypes and negotiate equitable relationships. For example, posts describe it as a strategy to ensure women contribute materially and to dismantle romanticized, imbalanced relationship models.

-

Some discussions emphasize its potential to foster fairness in relationships, particularly in response to perceived societal biases against men. However, these discussions are still niche and primarily occur within specific online communities, such as those associated with men’s rights or anti-gynocentrism.

Conclusion

The Gold Pill & Kinds Of Love, by Suviya

The following graphic was created by Suviya. It showcases many kinds of love classified by the ancient Greeks which still remain central to our lives today. Only one of the loves mentioned – the romantic – was unknown to the Greeks because it was constructed during the Middle Ages in Europe and only later imported throughout much of the world.

In the following graphic, the loves appearing above the line (pragma, agape, storge and philia) lend themselves to the formation of stable, traditional relationships. The loves appearing below the line (mania, philautia, romantic and pothos) are not compatible with rationally structured, reciprocal relationships because mania & pothos are irrational emotions, while philautia & romantic love are lacking in balanced reciprocity.

The two items on the right side of the image – eros and ludus – can be considered neutral, and are usually present in healthy, reciprocal relationships.

* * *

The graphic forms part of a larger discussion on something called ‘the gold pill,’ which is a philosophical framework that promotes balanced, reciprocal relationships by reintroducing principles of mutual investment and responsibility, inspired by historical practices like the dowry — without replicating them literally — as a way to restore dignity, structure, and fairness to modern partnerships.

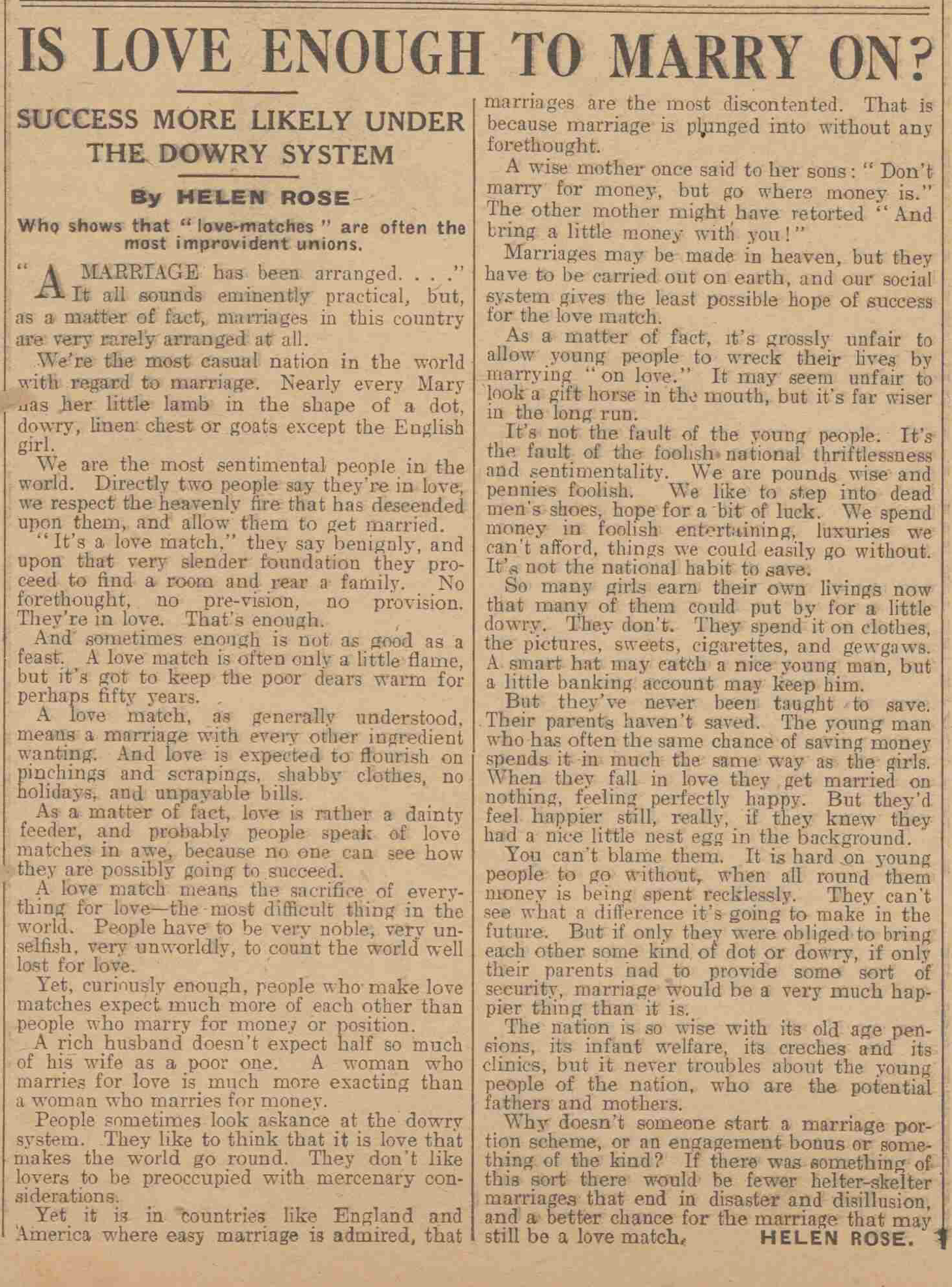

Is Love Enough To Marry On? (1927)

The evolution of gynocentrism via romance writings – Part 2

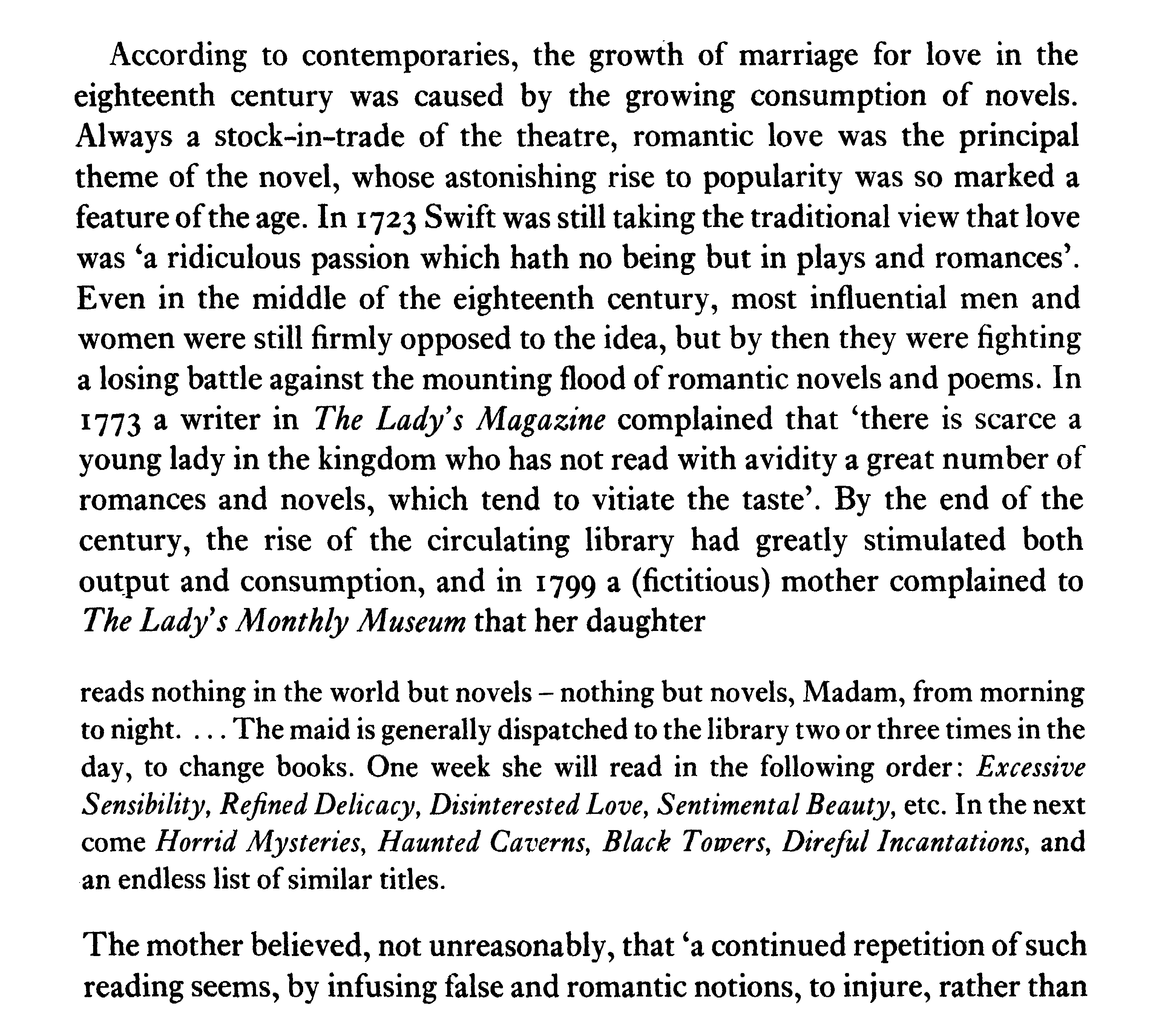

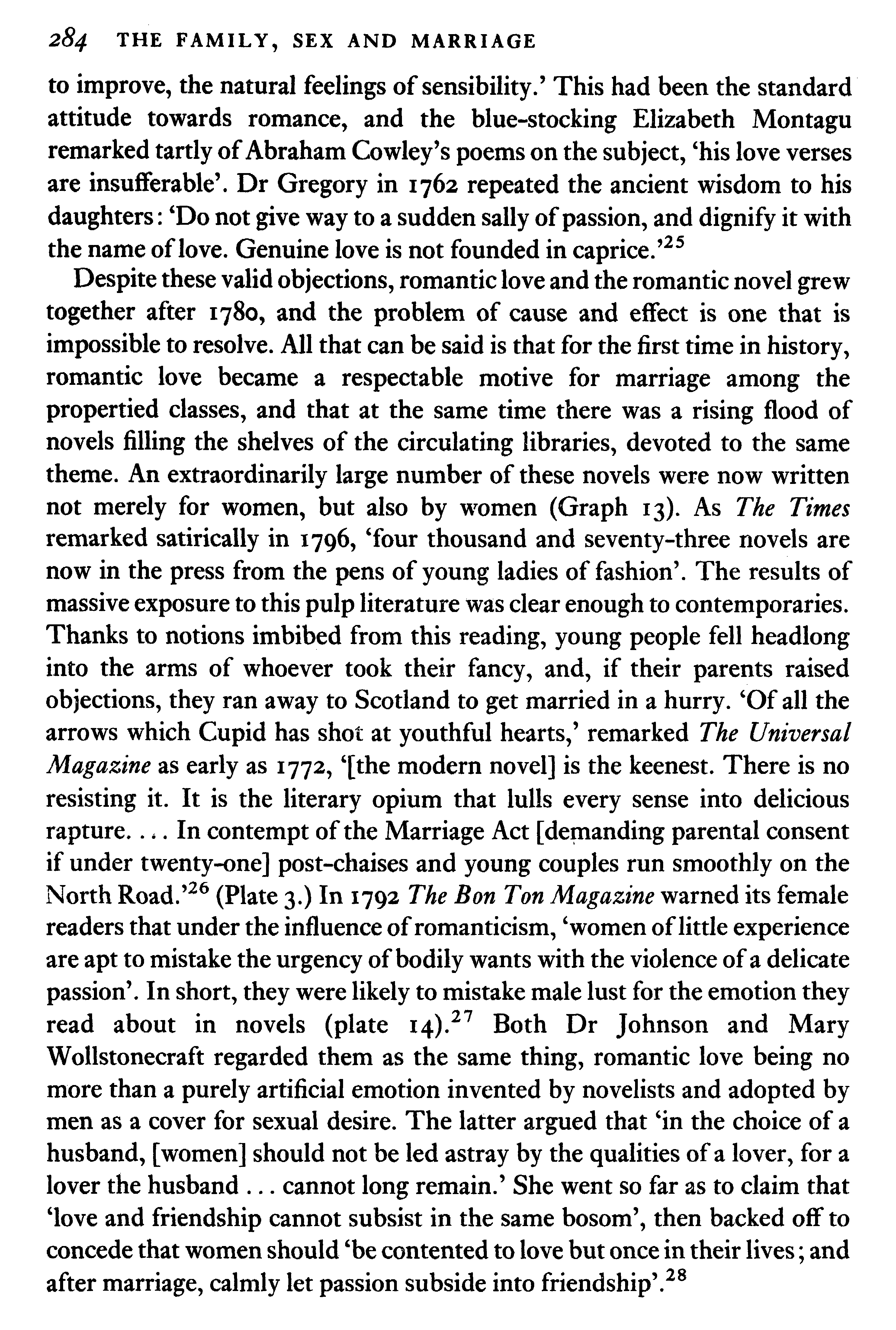

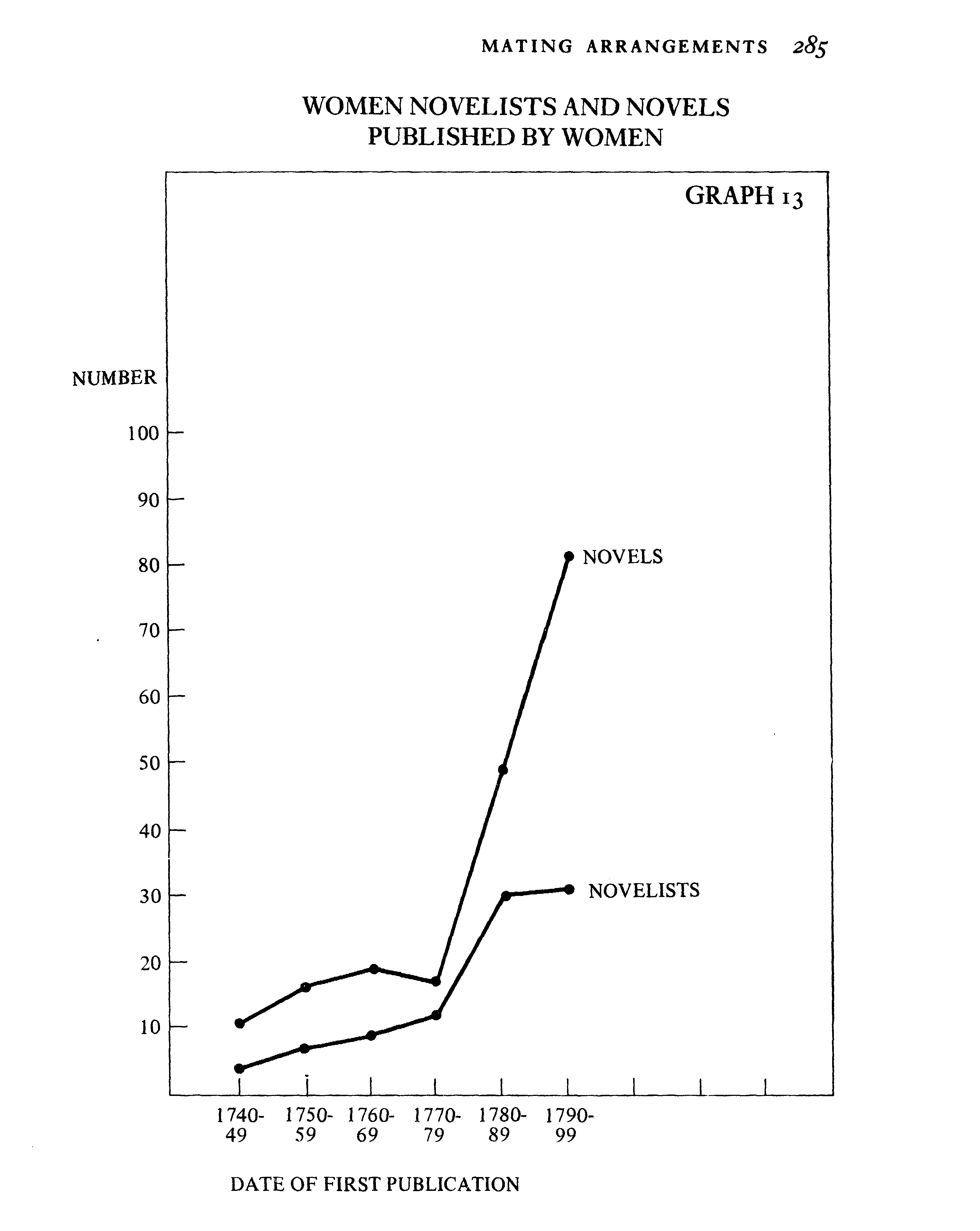

The following excerpt from The Family, Sex and Marriage in England, 1500-1800 by Lawrence Stone describes the timeline during which English marriages switched from traditional modes of arrangement and exchange of dowry, to romantic love as primary influence on relationship formation. This change, finds Stone, was stimulated by the rise of female-authored romance novels in the 1700s and their wide dissemination.

.

Note: A central link between these female romance writers and thier medieval forebears can be found in the English work Le Morte d’Arthur (1470) which was a retelling of medieval romantic tales by the English knight Sir Thomas Malory. Its influence on women’s novel writing in the 1700s, its broader impact on the romance genre, and the 19th-century Arthurian revival, helped to shape the literary landscape for women writers.

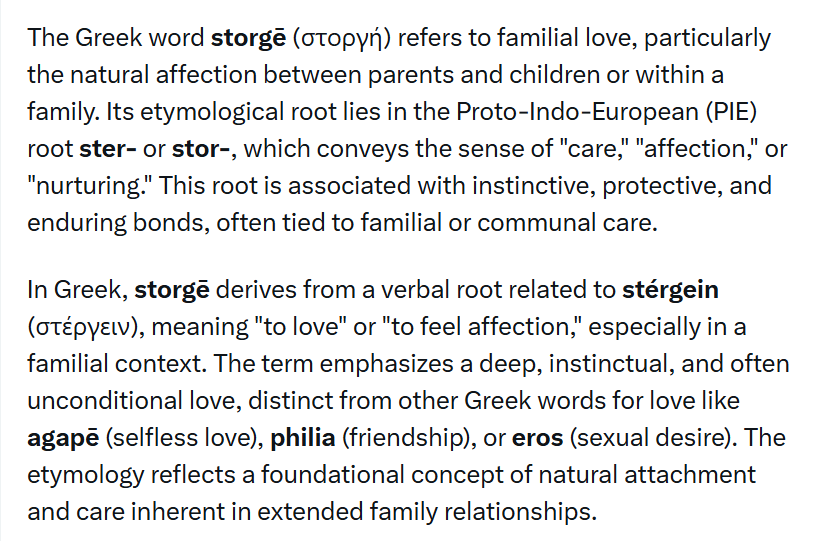

Storge: the root meaning

GROK gives the etymological root meaning of storge (family love):

Fulltext version:

The Greek word storge refers to familial love, particularly the natural affection between parents and children or within a family. Its etymological root lies in the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root ster- or stor-, which conveys the sense of “care,” “affection,” or “nurturing.” This root is associated with instinctive, protective, and enduring bonds, often tied to familial or communal care.

In Greek, storge derives from a verbal root related to stérgein, meaning “to love” or “to feel affection,” especially in a familial context. The term emphasizes a deep, instinctual, and often unconditional love, distinct from other Greek words for love like agape (selfless love), philia (friendship), or eros (sexual desire). The etymology reflects a foundational concept of natural attachment and care inherent in extended family relationships.

Gold Pill Philosophy

Below are a selection of articles exploring the dowry tradition, or what some have referred to as ‘gold-pill philosophy.’

– A Very Short Definition Of The ‘Gold Pill’ (Peter Wright)

– Taking the Gold Pill: A Paradigm Shift in Understanding Relationships

– Gold Pill Credo on Reddit (by iTrebor)

– This Is Shah: Why the Gold Pill?

– Urban Dictionary Definition for The Gold Pill (Mundus Imaginalis)

– The Gold Pill: Rebuilding Relationships With Ancient Wisdom (Sufjan S. Fannin)

– The Gold Pill: What It Can Do For A Civilization On The Brink (Sufjan S. Fannin)

– The Gold Pill: Checkmate, Trad Con-Artists (Sufjan S. Fannin)

– I Am the Table—Rethinking Contributions in Modern Relationships (Sufjan S. Fannin)

– An Early Call For The Gold Pill: A Cultural Convention Condemned – (1948)

– The Discussion – The Gold Pill Emerges (with Paul Elam and Shah)

– The Gold Pill & Kinds Of Love (by Suviya)

– Gold Pill And The Modwife (by Vernon Meigs)

– ThisIsShah Comments On Potential First Gold Pill Overdose

– Gynocentric vs non-gynocentric values for men (Peter Wright)

– This Could End the Hypergamy Death Spiral? (Effective Purpose & This Is Shah)

This Is Shah: Why the Gold Pill?

To those wondering why we created the gold pill, we did so to offer something beyond the typical Manosphere talking points which in recent times have become tired and stale.

As the voice behind the This Is Shah YouTube channel, I have spent my efforts excavating the lost knowledge of marriage transactions in human history. This field has been well documented by anthropologists, especially from the 60’s and 70’s onward. and includes information about marriage transactions such as the Dowry and Bridewealth (formerly Brideprice). Take this quote from The Economics of Dowry and Brideprice by Siwan Anderson:

Most societies, at some point in their history, have been characterized by payments at the time of marriage. Such payments typically go hand-in-hand with marriages arranged by the parents of the respective spouses. These marriage payments come in various forms and sizes but can be classified into two broad categories: transfers from the family of the bride to that of the groom, broadly termed as “dowry,” or from the groom’s side to the bride’s, broadly termed as “brideprice.” Brideprice occurs in two-thirds of societies recorded in Murdock’s (1967) World Ethnographic Atlas of 1167 preindustrial societies. Conversely, dowry occurs in less than 4 percent of this sample. However, in terms of population numbers, dowry has played a more significant role, because the convention of dowry has occurred mainly in Europe and Asia, where more than 70 percent of the world’s population resides.

However, somehow the manosphere has managed to completely miss this information and what it means for relationships in the modern world. I, and the others here who have taken the Gold Pill, aim to correct this.

We have a trove (or rather a dowry chest) full of information which include academic/scholarly papers, newspaper articles, and media from different time periods that more than demonstrate, decisively and precisely, how the marriage market operated with regard to economics and the material concerns of both parties involved.

As the r/goldpill_ subreddit develops, I plan to share what I have and it is my desire to see this forum become a place of honest discussion between participants who wish to understand and absorb the gold pill better. Ultimately, I would like to see people, especially men, process this information in a way that will help us to collectively bargain and negotiate better for marriage and within relationships, in a way that is fair and just. The memory of this information I believe will be necessary to help men navigate the uncertain future we have ahead of us.

Are we going back to the way things were? No, we are not, not in my belief, the world has experienced too many changes, and nothing short of a collapse and total reset will take us back to how things used to be. However, with this knowledge, we will craft a new way forward that gives to each what is owed.

-Shah