Article by Raymond Cormier

| ABSTRACT:

The title, “You Make Me Want to Be a Better Man”, is an unforgettable quotation from As Good As It Gets, the Jack Nicholson–Helen Hunt masterpiece (with Greg Kinnear). It occurs at about the midpoint in the 1997 film and Carol (played by Hunt) responds to Melvin (Nicholson) that it’s the best compliment she’s ever had in her life. As Roger Ebert quips: “It becomes clear that Melvin has been destined by the filmmakers to become a better man: First he accepts dogs, then children, then women, and finally even his gay neighbor.” Nevertheless, Melvin does change his ways and, under the influence of love, completely redirects his behavior.

I explore courtly love values in several contemporary movies, for example, Casablanca (1942), Roxanne (1987), Pretty Woman (1990), Beauty and the Beast (Disney 1991), Hercules (Disney 1997) Slumdog Millionaire (2008), and Tangled (2010). The hero or heroine saved through love and/or self-sacrifice constitute a guiding thread of the article; another focus is the “major personality shift” of the hero/heroine under the influence of love; and a third theme is the “quest and rescue” of the beloved. My diverse sources (comparanda) reach back to Marie de France’s courtly lai, Lanval as well as to the ineffable motifs of troubadour love service and the joy and largess/generosity emblematic of St. Francis of Assisi. |

In his recent monograph, The Making of Romantic Love, William Reddy observes that the eleventh-century Gregorian Reform brought with it condemnations by the Church—seeking to eliminate “polluting” sexual desire among Christians—and thus proposed severe new constraints on marriage and sexual behavior. It is argued further that in response, European secular poets and romancers—like the troubadours—devised a furtive way around the whole matter, namely, by inaugurating what is called today romantic love. This dualistic new creation, which opposes love and desire and was forged in the context of honor and secrecy, is found by Reddy to have a far-reaching influence (361), though not universal, yet uniquely Western and principally cultural in origin (i.e., not biological or neurological).1

With regard to romantic love, Reddy’s three case studies (medieval Europe, South Asia and Heian Japan) examine court codes in particular, and for the Europeans, he deduces that spiritualized love incorporated selfless devotion (370) as well as radical dissent (352) from the Church’s “cosmic order.”2 Adherents to the new values embraced, it would seem, individual conscience over blind obedience to the Church. Relative to our topic (in a work devoted in fact to women troubadours) one finds these words ‘of new values:’

“In exchange for their prostration, the troubadours expected to be ennobled, enriched, or simply made ‘better’: ‘Each day I am a better man and purer / for I serve the noblest lady in the world […]’”.3

Some of the films considered here belong to the “romantic comedy” genre, analysis of which is exemplified by the 2003 study by Deleyto, “Between Friends.” For such works, a tripartite categorization is proposed4: “nervous romance (tension filled),” “new romance (featuring independent women),” and “deceptive narratives” (fashionable and highlighting “constructions of a representation” in spite of soundtracks with old love songs).

Deleyto finds that friendship, in many films, is more important than love (171), and that the greater presence of female friendship signals the malleability of the genre (176). Deleyto writes (168): “[… an] unexpected new tendency has arisen within [the genre] over the last fifteen years or so in a growing number of contemporary romantic comedies, heterosexual love appears to be challenged, and occasionally replaced, by friendship.”

In this article, however, I intend to explore not friendship, not film weddings and not specifically the romantic comedy film in any significant way. Rather, I examine what may be named courtly values—as part of the courtly legacy from the Middle Ages—in over a dozen modern movies, from Casablanca (1942) to Tangled (2010). “Hero/heroine saved through love and/or self-sacrifice” will be one guiding thread of the analysis. Another focus is the “major personality shift” of the hero under the influence of love (as seen to a degree in As Good As It Gets, even more so in Pretty Woman). A third theme is the “quest and rescue” of the beloved (this can even be from a loveless marriage, as found in Excalibur). Films were selected among a number of successful productions, because they illustrate the prevalence of the themes in question.5 Limitations of space will prevent examination of other films that may suggest to some readers further links to courtliness, to the courtly legacy or to any number of medieval costume dramas.6

My hypothesis should be stated clearly: courtly values were palpable—neither a medieval fantasy nor a Romantic invention. This conjecture still needs to be put to scientific testing, which I will leave to other scholars to prove or refute. A more systematic survey, for which there is no space here, would likely reveal a significant imprint of the same themes on a wide range of contemporary films.

Such values and courtly love (the usual term is fin’amors, “true, fine, refined love”) survive to an extent today, a viewpoint not shared by all scholars.7 In his monograph Ennobling Love, Stephen Jaeger, while not using the fraught terms “courtly love” or “courtly legacy,” does assert that medieval “spiritualized” or “charismatic” love did not die out as such (5-6), though in his conclusion (212) he observes that “the paradigm of ideal love”, once established in medieval, early modern and modern narratives, is then destroyed “by revealing its false and destructive side.”

The term itself was invented in the late nineteenth century as a way of characterizing relationships found principally in French romances and poetry popular in the twelfth and thirteenth century, which were produced in and for, and which have been seen to emblemize court settings.8 Such love (for me, obviously, much more than a stylized game of flirtation), in the poetic context, is true, joyful and intense; it harmonizes with the commonweal and with divine intentions. Love brings, as we shall see, abundant feelings of liberation, of transformation and self-actualization. Jane Burns concedes the significance of courtly love when she concludes (48):

[…] despite its heteronormative veneer and its tendency to displace and occlude women as subjects, courtly love, when taken as the full range of amorous scenarios staged between elite heterosexual couples in a court setting, offers models for love relations that disrupt the binary and exclusive categories of male and female and masculine and feminine used typically to structure the Western romantic love story.

While the influence of powerful troubadour motifs is undeniable, let us cite here one brief northern French text as a kind of shorthand, for emphasis. It is a brief narrative or lai that illustrates certain courtly values.

Lanval, Marie de France’s eponymous hero, is a sad, forlorn Arthurian knight, abandoned, lonely, and helpless. An otherworldly sequence brings to him a wealthy and supremely stunning noblewoman (a fairy princess) with whom he becomes “well lodged.” His liberation from the bonds of solitary abandonment lead to liberality (he now gives freely to all comers), the medieval ideal of generosity, “the queen of virtues.”9 Kindness and love rescue him, as they do several male characters in modern film.10 Northern French poets emphasized too the “chivalry topos,” that is, that love motivates the knight in love and he becomes a better person through his adventures, thus meriting his beloved all the more. Noble love ennobles; in this better world too (for Auerbach), the apolitical “feudal ethos” encompasses “self-realization” (116-117). Clearly, we cannot accede to the damning proclamation of D. W. Robertson:

The study of courtly love, if it belongs anywhere, should be conducted only as the subject is an aspect of nineteenth and twentieth century cultural history. The subject has nothing to do with the Middle Ages, and its use as a governing concept can only be an impediment to our understanding of medieval texts. (18)

Courtly thinking existed in the Middle Ages and is manifested in the modern era.11 Each of the films we analyze here will of course not yield up every feature of the courtly mode, but still I sense that there is enough medieval residue and resonance in each to justify the argument, that, as some might put it succinctly, “courtly themes continue to generate artistic creation.” Along these lines, one wonders if the strong continuity of the Troubadour ethos—in particular that longing for a “far-away love”—is what underlies the resonances and residues. Love stories, requited or not, remain viable even in today’s hip-hop world.

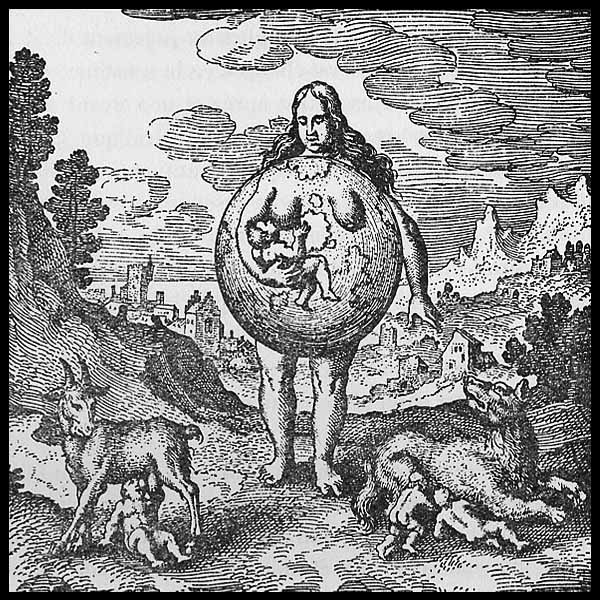

It has been reasoned that the two principal and most admired modes of courtly behavior were generosity and joy. Aristocratic courtly culture held that “the lady” was lord, and the lover’s role was to serve her, to sing about her merits and qualities, and carry out all imaginable actions to remain or become worthy of her, in a word, to deserve her.12 The function of love in this context was as dictated by the De amore of Andreas Capellanus (ca. 1185): “Love easily attained is of little value; difficulty in obtaining it makes it precious” and “Everything a lover does ends in the thought of the beloved.”13 For Auerbach, the synthetic term corteisie embodied values like the “refinement of the laws of combat, courteous social intercourse, service of women” (117).

In what is dubbed the long European twelfth century (1050-1250), French humanism predominated, a phenomenon already analyzed historiographically at length. As Italianist Ronald Witt recently put it (2012: 317): “The term ‘humanism’ aptly describes French culture in the period […].” In this context, interior monologue and dialogue arose from a new awareness of the interior life (the unique individual is now consciously separate from the court), which was further linked to the chivalric adventure/quest whereby audiences yearned for the unusual and the marvelous—now stimulated especially by wondrous stories brought back from the East by returning Crusaders (in particular the First-ca. 1100, and Second-ca. 1150). In discussing this particular type of medieval love, Aldo Scaglione has written (559):

The radical interiorization of the love experience carried with it the impossibility of communicating with the love object (topos of ineffability). Not only did poets profess themselves incapable of communicating to the beloved the depth of their passion, but the very lack of communication was for them both a sign of its depth and a consequence of it, to the point of entailing the complete physical absence of the lady.

Transformation through kindness and love, the frequent quest motif, the rescue of the hero/heroine—such are the narrative innovations associated with these elements (even the ineffable moment can be noted in at least one film, Roxane). Allied terms include honesty and humility—for perfection of the knight depended on his courtly worth, manifested through continuous bravery and feats of arms, humbly accomplished so to enhance and vouchsafe his honor and his nobility. Such aims for flawlessness were mirrored by the lady’s perfection, inspired too by her knight/liege. Of course, adultery occurs as co-incidental in this context, as does a “religion of love,” whereby mutual suffering and adoration are obligatory14. Let us see how all this plays out in the series of films selected for analysis.

The romantic comedy As Good As It Gets, the Jack Nicholson and Helen Hunt masterpiece (with Greg Kinnear), has provided the main title of this essay. The iconic line, “You Make Me Want to Be A Better Man,” is spoken by the misanthropic Melvin Udall (Jack Nicholson), whose obsessive-compulsive behavior and pathological germophobia strangle all of his human interactions. In the penultimate sequence, after he affronts and insults Carol (played by Hunt), his apology, necessary to get back into her good wishes, is a confession that he wants to merit her and deserve her respect (enough so that he can have their relationship return to its prior arrangement). One can say that all his motivations are selfish (arranging to care for Carol’s asthmatic son, putting up with his gay artist neighbor and then the neighbor’s dog), yet he is redeemed in the end, having moderated somewhat his odd manners.15 If not mere empathy, a kind of love is born in Melvin’s heart—even for his gay neighbor, for the dog, even for his neighbor’s African-American agent, and especially for Carol. For in the end, he is “a better man.”

Perhaps no genuinely touching and dreamlike modern film has captioned courtly features as much as Pretty Woman (1990), in which the Richard Gere character (Edward) undergoes a major personality shift, from ruthless business tycoon to generous shipbuilder, as a result of his experience of love for/with (an apparently) blonde streetwalker named Vivian (played by Julia Roberts).16 The wig disguises, as it were, her true personality. Over and above the film’s obvious Cinderella theme, it has been argued in fact, in a reversal of traditional gender roles, that it is she, Vivian, who, as the “Fair Unknown” (Scala 35), is transformed from “veiled” Hollywood Boulevard prostitute into a truly “noble character,” a change attributable to soul-sharing (with Edward—neither “wimp nor wild man”17), catalyzed by the experience of a San Francisco opera performance focused on the heroine Violetta (La Traviatta). Vivian’s real character is revealed too in an early scene when she drives, like a NASCAR expert, Edward’s sports car, then again in the bathtub scene, where she sexually enfolds him in her extra-long legs.

But, after their goodbyes, when Edward unexpectedly returns (in a white stretch limo) to Vivian’s apartment at the very end of the film, he scales the fire escape (in spite of his fear of heights) to “rescue the princess in the tower.” He has undergone a total conversion, from emotionless corporate raider to brave, forgiving and loving human. Tellingly, he asks the now red-haired (and post-feminist) Vivian what happens after the knight rescues the princess, she replies that she saves the hero “right back,” another revelation of a “reversal of gender roles” (Scala 38).18 And, as Genz recently put the question of the “post-feminist woman” (PFW). The PFW wants to “have it all” as she refuses to dichotomize and choose between her public and private, feminist, and feminine identities. She rearticulates and blurs the binary distinctions between feminism and femininity, between professionalism and domesticity, refuting monolithic and homogeneous definitions of postfeminist subjectivity.19 Reddy, in his analysis of this film posits it as a mirror of the sexual revolution of the 1960s and 1970s (380-381), whereby prostitution is permissible and sexual desire is destigmatized, but still stands in opposition to love, since both characters, now mutually devoted to each other, give up their life of “mere appetites.”20 Edward is thus a better man, Vivian a better woman.

Going back now to the World War II era, we will glance briefly at the great 1942 classic, Casablanca, in which, again surprisingly and ironically, the bitter and cynical refugee hero Rick Blaine (Humphrey Bogart) is transformed not by passionate love, but in this case through a self-effacing compassion. He just wants his beloved Ilsa (the woman between two men story), played famously by Ingrid Bergman) to be happy, for, as he remarks to her—“We’ll always have Paris.” In the final sequence, Rick, his tough-guy veneer now gone, surrenders two objects, one tangible, the other human—i.e., the vital letters of transit for transport out of Morocco, along with his chance for love with Ilsa. In a meeting with her and her husband Lazlo (the Resistance-fighter) at the Casablanca airport, the now-noble Rick swallows his resentment toward her and yields himself to a new emotion, empathy mixed with admiration for both Ilsa’s devotion and Lazlo’s political cause. And he opines: “It doesn’t take much to see that the problems of three little people don’t amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world.” In a dramatic gesture of magnanimity, Rick turns Ilsa over to the freedom fighter. Generosity and self-sacrifice redeem the hero as it will the other protagonists, even in different ways.

At this point, we will turn to three animated films (one of which is inspired by a live-action archetypal film produced just a few years after Casablanca). I refer to Beauty and the Beast, known today mainly through the 1991 Disney version. The lesser-known account that inspired the modern and magical remake is the Jean Cocteau classic, a contemporary parable based on a seventeenth-century French tale. The flawless Belle—to pay for her father’s transgression and obliged to dwell within the Beast’s castle—finds the beast repulsive, but, eventually, love is the potion that will transform both her and the Beast within; he is saved through Belle’s own generous change of heart as she responds to his kindness and favors. Similarly, Belle’s pity, patience, growing admiration and slowly-receding fear of the Beast, brings her to lower her guard and embrace the creature. Once she does love him (as foretold), the enchantment magically evaporates, the Beast is tamed and everything is joyfully transformed—by their love and new-found respect for each other.21

Redemption of a different sort rescues the mythological hero Hercules from the depths of weakened loss and despair. In this 1997 Disney film, the once-powerful and immortal youth attempts to save the life of Megara, his beloved (to provoke the hero, she was slain by Hercules’ nemesis Hades). His awesome powers had been taken from him by the villain but Hercules miraculously regains his strength through mutual love, and is on his way to become a “true hero”— just as (Samson-like) he lifts a huge column that had fallen on Meg. He is wholly and joyfully restored—by love—as a proper and divine hero, and elevated to Mt. Olympus.

In Disney’s 2010 Tangled, the heroine Rapunzel undergoes a major personality shift as a result of her encounter with the hero Eugene. It is in fact he who is responsible for getting her out of the imprisoning tower (using a ruse along with the appeal of the mysterious tiara—it’s hers, it is discovered, and she’s the princess!). In an interesting twist and role-reversal, Eugene tells Rapunzel that she was his new dream and Rapunzel says he was hers. Eugene dies in Rapunzel’s arms. In despair, Rapunzel sings the “Healing Incantation,” and begins to cry. Moved by her love and kindness, the last remnants of a magical flower’s enchantments condense in her tear, which heals Eugene. Later, the two return to the castle to meet her parents and eventually marry, living happily ever after. Rapunzel is redeemed through reciprocal love.

One must expect courtly themes in a medieval film like Excalibur (1981), set presumably in the late fourteenth or fifteenth century, bearing “mythical truth, not historical,” according to its director John Boorman.22 When the charismatic character of Lancelot first appears, he battles with Arthur’s knights, then with Arthur himself. Summoning such superhuman power that the sword Excalibur is cracked in half, Arthur overcomes Lancelot, though the new champion enigmatically but with great nobility bows to the king and offers him fealty. With the twelve-year peace across Britain established, along with the Round Table and its famed fellowship, Arthur proclaims he will marry. The relationship between Lancelot and Guinevere at first encapsulates what Scaglione named (see above) the “impossibility of communicating with the love object (topos of ineffability).”

But then, while escorting the bride Guinevere to the wedding (each, now love struck, having already undergone a coup de foudre), Lancelot is asked by her if he will find a soul mate to love and marry. His reply goes like this: I have found someone. It is you, Guinevere. I will love no other while you live. “I will love you always as queen and wife of my best friend.” Several scenes later, the queen is charged with adultery and Lancelot (now aware of her unhappy marriage) is at once named her champion—to defend her honor.

Such a scenario is familiar to scholars, but surely the millions of non-specialists who have seen the film must relate somehow to this courtly episode. As if enacting a Occitan love lyric, each has been mightily unfaithful: Guinevere in her longing glances, Lancelot in his fixed staring. But finally they must surrender to their passion. Their shameful infidelity, a deep wound, paralleled by Arthur’s own (unwilling) incestuous coupling with his half-sister Morgana, brings on a terre gaste, a horrid, morbid and gross wasting of both Arthur’s body and the land. The courtly and anti-courtly elements here predominate: the lovers’ religion of love easily nullifies any idea of a stylized game of flirtation. No one is improved this time.

In the romantic comedy, Roxanne (1987), brilliantly adapted by Steve Martin from Rostand’s Cyrano de Bergerac, the astronomer heroine (Daryl Hannah) argues with the genuinely courtly hero (C. D. Bates, Martin’s tennis-playing fireman). In the final sequence (to this woman between two men story) the hero reveals himself as the epitome of generosity by interceding for another man and wooing the heroine on his behalf. Bates says in the end that all Roxanne wanted was the perfect man who was both physically beautiful, emotionally mature and verbally adept. Finally, Bates (who loved her from the beginning, but direct communication with her was not possible—once more, the ineffable!) and Roxanne forgive one another as she confesses her love for him, in spite of his extraordinarily characteristic nose: it gives him uniqueness, she thinks, observing that flat-nosed people are boring and featureless. Feelings of compassion, admiration, tenderness and understanding change her point of view. The joyful humor and big-heartedness of the film charm the viewer.

We turn next to a blockbuster, the mysterious 1999 science fiction “cyberpunk-cyber thriller,” The Matrix. Amidst all the computer-generated graphics, amazing action scenes and visual effects, futuristic costumes, the enigmatic significance of The Matrix itself, and the secretive feelings Trinity (Carrie Ann Moss) experiences for the hero, Neo (Keanu Reeves), the story really embodies a simple and beautiful fairy-tale component. Trinity’s destiny was to fall in love with “the One” (prophesied as a savior-healer and super manipulator of The Matrix). The romantic relationship of the two is not revealed until the very end of the film, but Trinity’s act of kissing Neo powerfully resuscitates him within the sentient world (his interfaced physical body) and within The Matrix as well, where his avatar has been active. It is a phenomenal moment when the obscure meaning of The Matrix, Trinity’s love (from afar!) for Neo and Neo’s resurrection and fate are revealed all at once. Trinity does not have to quest for Neo: his sentient body remained right there with her in the laboratory. One can argue that Neo’s life is saved (literally) through the efforts and love of a beloved: Trinity has loved Neo all along. One can also posit that Neo’s acceptance of his destiny as “the One” is augmented by his awareness of Trinity’s love for him.

At the very opening of the film’s sequel, The Matrix Reloaded, the two have now become lovers, and, in one of the film’s final sequences, Neo has a choice: save mankind from extinction (it would happen through a “system reboot”), resulting in the survival of the destructive machines (but not humanity), or choosing to save Trinity’s life: in a face-to-face battle with an Agent (humanoid robot of The Matrix), she crashes out of a window and a bullet pierces her heart. In his abbreviated and breathtaking quest, Neo catches her in mid-air, but she dies. Loath to allow Trinity’s death, Neo uses his superhuman abilities to remove the bullet and revive her. The balance of the two scenes is perfect: in The Matrix it is Trinity who rescues Neo, while in the sequel Neo the hero saves his beloved through love. These films do not illustrate every aspect of courtliness or court culture, but the revealing moment does transport the viewer to a realm of heightened emotion. As in Hercules, love reigns supreme.23

Our final film is Slumdog Millionaire, billed as a kind of bildungsroman, a straightforward story about Jamal Malik, an eighteen-year old orphan from the slums of Mumbai. But the film has multiple strata, and underlying the story is Jamal’s search for his “far-away love”—a theme made legendary by twelfth-century Occitan poet Jaufre Rudel’s amor de lonh.24 As the film’s narrative revolves around “Kaun Banega Crorepati,” the Indian TV version of Who Wants To Be A Millionaire? each chapter of Jamal’s increasingly layered story reveals where he learned the responses to the show’s seemingly impossible questions. To witness the unfolding of Jamal’s life journey—surviving as a street urchin/career thief, his many colorful adventures, gang encounters, his job serving tea in a call center—helps to explain several mysteries, like how and why he ended up as a featured contestant, but most especially how he knows the answers. His life story—in reality a quest—includes being orphaned at an early age; growing up with an older brother, who was both his guardian/protector and antagonist (a kind of rival and dark “other”); and having a relationship since childhood with another orphaned child, a girl named Latika.

A parallel plot line deals with the law—in the present-time episodes, the police grill him to determine how Jamal can be doing so well on the show when others who are brighter, more educated and wealthier fail. Is he cheating? Is it purely luck? But the fact is, the complex and interwoven story is simply a tale of love: every action of Jamal is motivated by his search for his lost childhood love, Latika. The resplendent joy manifested in the final sequences—an emblem, we recall, of courtly life (Battais 135)—unlocks all the puzzles and enigmas of the film.25 With great generosity of character, Jamal, enduring and shaking off all sorts of suffering and pain, was searching endlessly for Latika: that is why he found a way to get himself recruited to be a contestant for the game show, for he knew she would be watching and that they would be able to meet together, finally, at a designated locale, and no doubt live “happily ever after” and in joy.26

As we have seen, in these selected films (and in many other contemporary ones) transformation through kindness and love frequently manifests itself as a part of the finale. The quest motif very often subsumes the conversion—not necessarily as dramatic as an Augustinian one—yet nevertheless resulting in the rescue of the hero/heroine, where rescue is a generic term including redemption, resuscitation and/or vindication. Melvin Udall, Edward and Vivian, Lancelot, Neo and even Rick Blaine—all are made over or made better by love. Beauty and the Beast, Hercules, Rapunzel and Eugene—these are characters transformed from within; Jamal Malik’s life quest, motivated by a far-away love, ends in a glorious epiphany. An explanatory rationale for the preceeding essay might suggest how faintly aware of these themes our readers might be, but the need remains to inform them of their exact correspondence with courtly love themes. However much it has been transplanted, the courtly legacy sustains. And “the better man” (or woman) survives today.

Works Cited

- 10. Dir. Blake Edwards. Orion Pictures, 1979. Film.

- Aberth, John. (2003). A Knight at the Movies: Medieval History on Film. New York: Routledge.

- As Good As It Gets. Dir. James L. Brooks. Gracie Films, 1997. Film.

- At First Sight. Dir. Irwin Winkler. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), 1999. Film.

- Auerbach, Erich. (1957). Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature. Trans. Willard Trask. Garden City, NY: Doubleday Anchor.

- Battais, Lise. “La Courtoisie de François d’Assise: Influence de la littérature épique et courtoise sur la premi?re génération franciscaine.” Mélanges de l’Ecole française de Rome—Moyen-Age, Temps modernes 109 (1997): 131-160.

- Beauty and The Beast (“La belle et la b?te”). Dir. Jean Cocteau. DisCina, 1946. Film.

- Beauty and the Beast. Dir. Gary Trousdale and Kirk Wise. Walt Disney Pictures, 1991. Film.

- Bernau, Anke, and Bettina Bildhauer. (2011). Medieval Film (Filming the Middle Ages). London, Reaktion Books Ltd.

- Bogin, Magda. (1980). The Women Troubadours. New York and London: W. W. Norton.

- Burns, E. Jane. “Courtly Love: Who Needs It? Recent Feminist Work in the Medieval French Tradition.” Signs, 27 (2001): 23-57.

- Casablanca. Dir. Michael Curtiz. Warner Brothers Pictures, 1942. Film.

- Deleyto, Celestino. “Between Friends: Love and Friendship in Contemporary Hollywood Romantic Comedy.” Screen 44, 2 (2003): 167-182.

- Driver, Martha W., and Sid Ray. (2004). The Medieval Hero on Screen: Representations from Beowulf to Buffy. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland.

- Duby, Georges. ”Le modèle courtois,” in Histoire des femmes en Occident, ed. G. Duby and M. Perrot (v. 2, Le Moyen Âge, ed. Ch. Klapisch-Zuber). Paris: Perrin, 1991.

- Elliott, Andrew B. R. (2003). Remaking the Middle Ages: The Methods of Cinema and History in Portraying the Medieval World. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland.

- Excalibur. Dir. John Boorman. Orion Pictures; distributed by Warner Bros., 1981. Film.

- Fatal Attraction. Dir. Adrian Lyne. Paramount Pictures, 1987. Film.

- Finke, Laurie A., and Martin B. Shichtman. (2003). Cinematic Illuminations: The Middle Ages on Film. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP.

- Galician, Mary-Lou. (2002). Sex, Love, and Romance in the Mass Media Analysis and Criticism of Unrealistic Portrayals and Their Influence. Routledge Communication Series. New York and Oxford: Routledge.

- Genz, Stephanie. “Singled Out: Postfeminism’s ‘New Woman’ and the Dilemma of Having It All.” The Journal of Popular Culture 43 (2010): 97–119.

- Grossel, Marie-Geneviève. “Remarques sur le motif du ‘service d’amour’ chez quelques trouvères des cercles champenois.” Cahiers de Recherches Médiévales 15 (2008): 265-276.

- Grice, Paul. (1989) Studies in the Way of Words. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Hercules. Dir. Ron Clements and John Musker. Walt Disney Pictures, 1997. Film.

- Hume, Kathryn. (1985) Fantasy and Mimesis: Responses to Reality in Western Literature. New York: Routledge.

- Jeffers-McDonald, Tamar. (2007) Romantic Comedy: Boy Meets Girl Meets Genre. London and New York: Wallfower.

- Johnson, Kimberly R., and Bjarne M. Holmes (2009) “Contradictory Messages: A Content Analysis of Hollywood-Produced Romantic Comedy Feature Films.” Communication Quarterly 57, 3 (2009): 352–373.

- Kantor, Jodi. “Elite Women Put a New Spin on an Old Debate.” New York Times June 22, 2012. Consulted online: .

- Kelly, Douglas. “Courtly Love in Perspective: The Hierarchy of Love in Andreas Capellanus.” Traditio 24 (1968): 119-148.

- Kim, Ji-hyun Philippa (2012). “Pour une littérature médiévale moderne: Gaston Paris, l’”amour courtois” et les enjeux de la modernité.” Coll. Essais sur le Moyen Age, n° 55. Paris: Honoré Champion.

- Leithart, Peter J. Zizek and Courtly Love. 4.29.15. http://www.firstthings.com/blogs/leithart/2015/04/zizek-and-courtly-love. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- Lewis, C. S. (1936) The Allegory of Love: A Study in Medieval Tradition. Oxford: Oxford UP.

- Marcabru. “L’autrier jost’una sebissa.” In The Medieval Pastourelle, vol. 1, edited and translated by William D. Paden, 36-41. New York: Garland, 1987.

- Marie de France.(1954) Lais. Ed. A. Ewert. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Monson, Don A. “The Troubadour’s Lady Reconsidered Again.” Speculum 70 (1995): 255-274.

- Novak, Michael. The Myth of Romantic Love. 2.14.11. http://www.firstthings.com/web-exclusives/2011/02/the-myth-of-romantic-love. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- Peberdy, Donna. “From Wimps to Wild Men: Bipolar Masculinity and the Paradoxical Performances of Tom Cruise.” Men and Masculinities 13 (2010): 231-254.

- Poètes et romanciers du Moyen Age, (1952) Ed. Albert Pauphilet. Pléiade. Paris: Gallimard.

- Pretty Woman. Dir. Garry Marshall. Touchstone Pictures and Silver Screen Partners IV, 1990. Film.

- Pugh, Tison, and Susan Aronstein, Eds. 2004. The Disney Middle Ages: A Fairy-Tale and Fantasy Past (New Middle Ages). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Raw, Laurence. “Imaginative History and Medieval Film.” Adaptation 5, 2 (2012): 262-267.

- Reddy, William M. (2012) The Making of Romantic Love: Longing and Sexuality in Europe, South Asia, and Japan, 900-1200 CE (Chicago Studies in Practices of Meaning). Chicago: U Chicago P.

- Robertson, D. W. (1968) “The Concept of Courtly Love as an Impediment to the Understanding of Medieval Texts.” in The Meaning of Courtly Love, ed. F. X. Newman. Albany, NY: State University of New York, 1-18.

- Roxanne. Dir. Fred Schepisi. Columbia Pictures Industries, IndieProd Company Productions, L.A. Films, 1987. Film.

- Saturday Night Fever. Dir. John Badham. Producer: Robert Stigwood Organization (RSO). Distributed by Paramount Pictures. 1977. Film.

- Scaglione, Aldo. “Petrarchan Love and the Pleasures of Frustration.” Journal of the History of Ideas 58 (1997): 557-572.

- Scala, Elizabeth. “Pretty Women: The Romance of the Fair Unknown, Feminism, and Contemporary Romantic Comedy.” Film & History 29 (1999): 34-45.

- Schultz, James A. (2006) Courtly Love, the Love of Courtliness, and the History of Sexuality. Chicago: U Chicago P.

- Slumdog Millionaire. Dir. Danny Boyle. Fox Searchlight Pictures and Warner Brothers Pictures, 2008. Film.

- Tangled. Dir. Nathan Greno and Byron Howard. Walt Disney Pictures, 2010. Film.

- The Matrix. Dir. Andy Wachowski and Larry Wachowski. Village Roadshow Pictures, Silver Pictures, Groucho II Film Partnership; distributed by Warner Bros. Pictures, 1999. Film.

- The Matrix Reloaded. Dir. Andy Wachowski and Larry Wachowski. Village Roadshow Pictures, Silver Pictures; distributed by Warner Bros. Pictures, 2003. Film.

- The Princess Bride. Dir. Rob Reiner. Act III Communications, Buttercup Films Ltd., The Princess Bride Ltd., 1987. Film.

- The Wild One. Dir. Laslo Benedek. Columbia Pictures, 1953. Film.

- Walsh, P. G., ed. and trans. (1982) Andreas Capellanus on Love. London: Duckworth.

- Witt, Ronald G. (2012) The Two Latin Cultures and the Foundation of Renaissance Humanism in Medieval Italy. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

- Zipes, Jack. (2011) The Enchanted Screen: The Unknown History of Fair-Tale Films. New York: Routledge.

Notes

Republished under Creative Commons licence 4.0