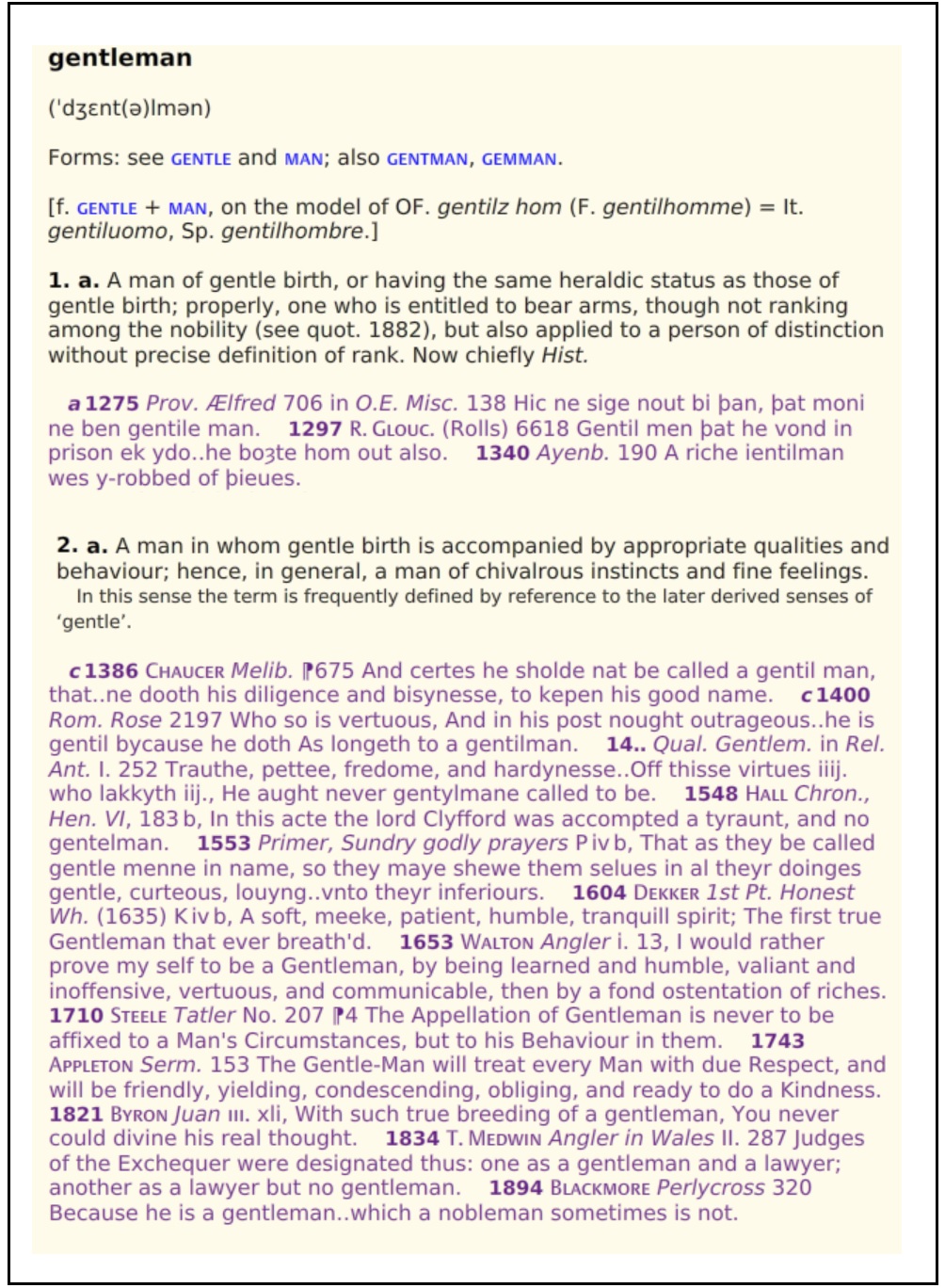

According to the Oxford Dictionary the term gentleman has been in use since the 1200’s and refers to (2.) “a man with chivalrous instincts and fine feelings”. ‘Gentleman’ therefore imples and is synonymous with chivalric behaviour and also serves as a replacement term for chivalry.

The myth of the perilous bed

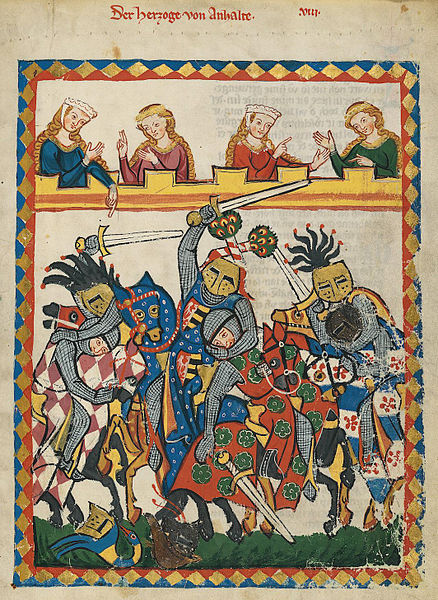

Joseph Campbell states of courtship in the Middle Ages, “If you wanted to make love to a woman, she’s already got the drop on you. The technical term for a woman’s granting of herself was merci; the woman grants her mercy. Now that might consist in her permission for the man to kiss her on the back of the neck once every Whitsuntide, you know, something like that – or it may be a full giving in love. That would depend upon her estimation of the character of the candidate. The essential idea was to test this man.”1 While there are numerous real examples of tests women asked men to endure, including jousting competitions and other dangerous activities, Campbell provides some fictional examples of tests such as, for instance, ‘the Myth of The Perilous Bed’:

“A number of knights had to experience the perilous bed before getting access to a lady, and it works like this; You come into a room that’s absolutely empty, except in the middle of it is a bed on rollers. You are to come in dressed in your full armour – sword, spear, shield, all that heavy stuff- and get into bed. Well, as the knight approaches the bed, it shears away to one side. So he comes again, and it goes the other way. The knight finally thinks, “I’ve got to jump.” So with his full gear, he jumps into the bed, and as soon as he hits the bed, it starts bucking like a bronco all over the room, banging against the walls and all of that kind of thing, and then it stops. Then he’s told, ‘It’s not finished yet. Keep your armour on and keep your shield over yourself. ” And then arrows and crossbow bolts pummel him- bang, bang, bang, bang. Then a lion appears and attacks the knight, but he cuts off the lion’s feet, and the two of them end up lying there in a pool of blood. Only then do the ladies of the castle come in and see their knight, their saviour, lying there looking dead. One of the ladies takes a bit of ‘fur’ from her garment and puts it in front of his nose and it moves ever so slightly – he’s breathing, he’s alive. So they nurse him back to health.”

Of this myth Campbell states,

“This is the masculine experience of the feminine temperament: that it doesn’t quite make sense, but there it is. That’s the way it’s shifting this time, that’s the way it’s going that time. The trial is to hold on, be patient and don’t try to solve it. Just endure it, and then all the boons of beautiful womanhood will be yours.” [Transformations of Myth Through Time].

This story provides a fascinating insight into the mechanics of gynocentrim. Before the 11th century there was hardly any support in the world for the notion of romantic love; at best it was an underground, unspoken activity disallowed on the world stage where arranged marriages dominated gender interaction completely. When the cult of romantic love appeared, women could for the first time be married and/or choose a male lover with the open encouragement of the society in which they lived. For the first time a woman would force her lover to do worthiness tests – get in a sword fight, a jousting battle, go on a dangerous journey, write some poetry, or procure and provide a precious gift. If he succeeded in her chosen test, he was often rewarded with a small gesture.

The cult of romantic love began in France and rapidly spread to the rest of Europe, and it was a watershed moment for women’s power. Women realised their bargaining power and could now ask for favours, worthiness tests and special treatment in exchange for love. It was here in 11th-12th century Europe that chivalry and gynocentrism were born, and without this event it unlikely that a ‘battle of the sexes’ would have developed, nor would there have been a need for feminists and men’s advocates to address the fluctuating power balance as exists between men and women today.

Sir Lancelot rides the Perilous Bed

[1] Joseph Campbell and Bill Moyers, The Power of Myth

Joseph Campbell on chivalry

An Interview with mythologist Joseph Campbell on the topic of chivalry, with Bill Moyers:

Moyers: So the age of chivalry was growing up as the age of romantic love was reaching out?

Campbell: The Middle Ages was a strange period because it was terribly brutal. There was no central law. Everyone was on his own, and, of course, there were great violations of everything. But within this brutality there was a civilizing force which the women really represented because they were the ones who established the rules for this game.

Moyers: How did it happen that the women had the dominant influence?

Campbell: Because if you want to make love to a woman, she’s already got the drop on you. The technical term for a woman’s granting of herself was merci; the woman grants her merci. Now, that might consist in her permission for the man to kiss her on the back of the neck once every Whitsuntide, you know, something like that – or it may be a full giving in love. That would depend upon her estimation of the character of the candidate… The essential idea was to test this man to make sure that he would suffer things for love, and that this was not just lust.

Moyers: Joseph, that may have emerged in the troubadour period, but it is still alive and well in East Texas.

Campbell: That’s the force of this position. It originated in twelfth century Provence, and you’ve got it now in 20th century Texas.

Moyers: Its been shattered of late, I have to tell you that. I mean, I’m not sure that it’s as much of a test as it used to be.

Campbell: The tests that were given then by women involved, for example, sending a chap out to guard a bridge. The traffic in the Middle Ages was somewhat encumbered by these youths guarding bridges. But also the tests included going into battle. A woman who was too ruthless in asking her lover to risk a real death before she would acquiesce in anything was considered sauvage or “savage”. Also, the woman who gave herself without the testing was “savage”. There was a very nice psychological estimation game going on here. [From – The Power of Myth].

Joseph Campbell on courtly love

Susan Sarandon introduces the following lecture by Joseph Campbell on the topic of chivalry and courtly-love as they took shape in the Middle Ages.

Susan Sarandon: “We like to think that romantic love is an idea as old as humanity. But it was only in the twelfth century AD that this concept appeared suddenly, not only in Europe, but in Islam and in India and the courts of East Asia. To quote Joe Campbell, for one brief shining moment in every castle in the world from the English Channel to the Persian gulf and the Sea of Japan, the one song was variously ringing the liege-man of love. Chrétien de Troyes was one of the great troubadours of this new song; he was the court poet to Marie de Champagne who ruled as the Queen Regent of France from 1181 to 1187 gathering around her the greatest poets of the age and inspiring a humanistic flowering that would lead in centuries to come to the renaissance.”

Susan Sarandon: “We like to think that romantic love is an idea as old as humanity. But it was only in the twelfth century AD that this concept appeared suddenly, not only in Europe, but in Islam and in India and the courts of East Asia. To quote Joe Campbell, for one brief shining moment in every castle in the world from the English Channel to the Persian gulf and the Sea of Japan, the one song was variously ringing the liege-man of love. Chrétien de Troyes was one of the great troubadours of this new song; he was the court poet to Marie de Champagne who ruled as the Queen Regent of France from 1181 to 1187 gathering around her the greatest poets of the age and inspiring a humanistic flowering that would lead in centuries to come to the renaissance.”

Joseph Campbell: “Our particular topic today is one that I think can serve to guide us from the general universal themes of myth into the material specifically of the European consciousness which we inherit. The period of the Authurian and Grail romances is dated almost precisely from 1150 to 1250 AD. And in the historical context of this second great phase of occidental culture (the first phase being that of the Greco-Roman periods starting with the Homeric epics) the period of the Authurian romances is the counterpart for the Gothic and modern worlds of the Homeric period for the Greco-Romans. That is to say, it is in that period that the main themes are stated and developed in terms of culture values and the spiritual dimension. The great works appear suddenly and this is the remarkable thing about the dawn of civilizations: within 200 years the whole thing is there and it wasn’t there before.”

Joseph Campbell: “Our particular topic today is one that I think can serve to guide us from the general universal themes of myth into the material specifically of the European consciousness which we inherit. The period of the Authurian and Grail romances is dated almost precisely from 1150 to 1250 AD. And in the historical context of this second great phase of occidental culture (the first phase being that of the Greco-Roman periods starting with the Homeric epics) the period of the Authurian romances is the counterpart for the Gothic and modern worlds of the Homeric period for the Greco-Romans. That is to say, it is in that period that the main themes are stated and developed in terms of culture values and the spiritual dimension. The great works appear suddenly and this is the remarkable thing about the dawn of civilizations: within 200 years the whole thing is there and it wasn’t there before.”

A male-positive approach to English literature

_____________________________________________________

SOURCE: NEW MALE STUDIES: AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL ~ ISSN 1839-7816 ~ VOL. 2, ISSUE 2, 2013 PP. 68-74 © 2013 AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE OF MALE HEALTH AND STUDIES Reproduced here with permission.

La Querelle des Femmes

The 800 year old Querelle des Femmes translates as the “quarrel about women” and amounts to what we today refer to as the gender-war. In its narrow sense, this term refers to a genre of Latin and French writing in which the superiority of one or the other sex has been proposed with the primary aim of determining the status of women.

The timeframe of the querelle begins in the twelfth century, and after 800 years of debate finds itself perpetuated in the feminist-driven reiterations of today (though some authors claim, unconvincingly, that the larger querelle came to an end in the 1700s).

For more about the history of La Querelle des Femmes, the following paper by historian Joan Kelly is instructive. The paper was written with a feminist focus thus leaving out all but the most superficial characterization of the male experience of gender relations. Nevertheless it provides much important history and for that I have no hesitation in recommending it.

* * *

Early Feminist Theory and the Querelle des Femmes

By Joan Kelly (1982)

We generally think of feminism, and certainly of feminist theory, as taking rise in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Most histories of the Anglo-American women’s movement acknowledge feminist “forerunners” in individual figures such as Anne Hutchinson, and in women inspired by the English and French revolutions, but only with the women’s rights conference at Seneca Falls in 1848 do they recognize the beginnings of a continuously developing body of feminist thought.

Histories of French feminism claim a longer past. They tend to identify Christine de Pisan (1364-1430?) as the first to hold modern feminist views and then to survey other early figures who followed her in expressing pro-woman ideas up until the time of the French Revolution. New work is now appearing that will give us a fuller sense of the richness, coherence, and continuity of early feminist thought, and I hope this paper contributes to that end.

What I hope to demonstrate is that there was a 400-year-old tradition of women thinking about women and sexual politics in European society before the French Revolution. Feminist theorizing arose in the fifteenth century, in intimate association with and in reaction to the new secular culture of the modern European state. It emerged as the voice of literate women who felt themselves and all women maligned and newly oppressed by that culture, but who were empowered by it at the same time to speak out in their defense. Christine de Pisan was the first such feminist thinker, and the four-century-long debate that she sparked, known as the querelle des femmes, became the vehicle through which most early feminist thinking evolved.

The early feminists did not use the term “feminist,” of course. If they had applied any name to themselves, it would have been something like defenders or advocates of women, but it is fair to call this long line of prowomen writers that runs from Christine de Pisan to Mary Wollstonecraft by the name we use for their nineteenth- and twentieth-century descendants. Latter-day feminism, for all its additional richness, still incorporates the basic positions the feminists of the querelle were the first to take.

![]() To read the rest of Joan Kelly’s essay online click here

To read the rest of Joan Kelly’s essay online click here

See also related: Querelle du Mariage

Modesta Pozzo: gynocentrism in 1590

Modesta Pozzo, a protofeminist living in the 1500s in Venice wrote a gynocentric work entitled The Worth of Women: their Nobility and Superiority to Men. The work purportedly records a conversation among seven Venetian Noblewomen that explores nearly every aspect of women’s experience in both theoretical and practical terms. The following excerpts begin with comments by one of the women, Corinna:

![]() Corinna said: “Helena has not managed to prove anything except that men do have some merits when they are married — which is to say, when they are united with a wife. Now that I don’t deny, but without that help from their wives, men are just like unlit lamps: in themselves, they are no good for anything, but, when lit, they can be handy to have around the house. In other words, if a man has some virtues, it is because he has picked them up from the woman he lives with, whether mother, nurse, sister, or wife — for over time, inevitably, some of her good qualities will rub off on him. Indeed, quite apart from the good examples women provide for them, all men’s finest and most virtuous achievements derive from their love for women, because, feeling themselves unworthy of their lady’s grace, they try by any means they can to make themselves pleasing to her in some way. That men study at all, that they cultivate the virtues, that they groom themselves and become well-bred men of the world –in short, that they finish up equipped with countless pleasing qualities– is all due to women.”

Corinna said: “Helena has not managed to prove anything except that men do have some merits when they are married — which is to say, when they are united with a wife. Now that I don’t deny, but without that help from their wives, men are just like unlit lamps: in themselves, they are no good for anything, but, when lit, they can be handy to have around the house. In other words, if a man has some virtues, it is because he has picked them up from the woman he lives with, whether mother, nurse, sister, or wife — for over time, inevitably, some of her good qualities will rub off on him. Indeed, quite apart from the good examples women provide for them, all men’s finest and most virtuous achievements derive from their love for women, because, feeling themselves unworthy of their lady’s grace, they try by any means they can to make themselves pleasing to her in some way. That men study at all, that they cultivate the virtues, that they groom themselves and become well-bred men of the world –in short, that they finish up equipped with countless pleasing qualities– is all due to women.”

Virginia said: “If it is true what you say, and men are as imperfect as you say they are, then why are they our superiors on every count?”

Corinna replied: “This pre-eminence is something they have unjustly arrogated to themselves. And when it’s said that women must be subject to men, the phrase should be understood in the same sense as we are subject to natural disasters, diseases, and all the other accidents of life: it’s not a case of being subject in the sense of obeying, but rather of suffering an imposition; not a case of serving them, but rather of tolerating them in a spirit of Christian charity, since they have been given to us by God as a spiritual trial. But they take the phrase in the contrary sense and set themselves up as tyrants over us, arrogantly usurping that domination over women that they claim is their right, but which is more properly ours. For don’t we see that men’s rightful task is to go out to work and wear themselves out trying to accumulate wealth, as though they were our factors or stewards, so that we can remain at home like the lady of the house directing their work and enjoying the profit of their labors? That, if you like, is the reason why men are naturally stronger and more robust than us — they need to be, so they can put up with the hard labor they must endure in our service.”

Leonora said: “A woman, when she is segregated from male contact, has something divine about her and can achieve miracles, as long as she retains her natural virginity. That certainly isn’t the case with men, because it is only when a man has taken a wife that he is considered a real man and that he reaches the peak of happiness, honor, and greatness. The Romans in their day did not confer any important responsibilities on any man who did not have a wife; they did not allow him to take up a public office or to perform any serious duties relating to the Republic. Homer used to say that men without wives were scarcely alive. And if you want further proof of women’s superior dignity and authority, just think about the fact that if a man is married to a wise, modest, and virtuous woman, even if he is the most ignorant, shameless, and corrupt creature who has ever lived, he will never, for all his wickedness, be able to tarnish his wife’s reputation in the least. But if, through some mischance, a woman is lured by some persistent and unscrupulous admirer into losing her honor, then her husband is instantly and utterly shamed and dishonored by her act, however good, wise, and respectable he may be himself — as if he depended on her, rather than she on him. And indeed, just as a pain in the head causes the whole body to languish, so when women (who are superior by nature and thus legitimately the head and superior of their husbands) suffer some affront, so their husbands , as appendages and dependents, are also subject to the same misfortune and come to share in the ills of their wives as well as in their good fortune.”

Leonora said: “Do you not really believe that men do not recognize our worth? In fact they are quite aware of it, and, even though envy makes them reluctant to confess this in words, they cannot help revealing in their behavior a part of what they feel in their hearts. For anyone can see that when a man meets a woman in the street, or when he has some cause to talk to a woman, some hidden compulsion immediately urges him to pay homage to her and bow, humbling himself as her inferior. And similarly at church, or at banquets, women are always given the best places, and men behave with deference and respect toward women even of a much lower social status. And where love is concerned, what can I say? Which woman, however low-born, is below men’s notice? Which do they shrink from approaching? Is a man of the highest birth ashamed to consort with a peasant girl or a plebian — with his own servant, even? It is because he senses that these women’s natural superiority compensates for the low status fortune has conferred on them. It’s very different in the case of women: except in some completely exceptional freak cases, you never find a noblewoman falling in love with a man of low estate, and, moreover, it’s rare even to find a woman loving someone (apart from her husband) of the same social status. And that’s why everyone is so amazed when they hear of some transgression on the part of a woman: it’s felt to be a strange and exceptional piece of news (I’m obviously excepting courtesans here), while in the case of men, no one takes any notice, because sin for them is a matter of course and an everyday occurrence that it doesn’t seem remarkable any more. In fact, men’s corruption has reached such a point that when there is a man who is rather better than the others and does not share their bad habits, it is seen as a sign of unmanliness on his part and he is regarded as a fool. Indeed, many men would behave better if it were not for the pressure of custom, but, as things stand, they feel it would be shameful not to be as bad as or worse than their fellows.”

Corinna said: “We’ve already proven that on all counts –ability, dignity, goodness, and a thousand other things– we are their superiors and they our inferiors. So I don’t see any reason why they shouldn’t love us, except for the fact that, as I said before, men are by nature so cold and ungrateful that they cannot even be swayed by the influences of the heavens. Though another factor, as we were saying earlier, is their great envy of our merits: they are fully aware of our worth and they know themselves to be full of flaws that are absent in women. For when men have flaws, women have virtues; and if you need proof, it’s quite obvious that in women you find prudence and gentleness where men have anger; temperance where men have greed; humility in place of pride; continence in place of self-indulgence; peace in place of discord; and love in place of hatred. In fact, to sum up , any given virtue of the soul and mind can be found to a greater degree in women than in men.”

Cornelia exclaimed: “What poor wretches men are not to respect us as they should. We look after their households for them, their goods, their children, their lives — they’re hopeless without us and incapable of getting anything right. Take away that small matter of their earning money and what use are they at all? What would they be like without women to look after them? (And with such devotion) I suppose they’d rely on servants to run their households — and steal their money and reduce them to misery, as so often happens.”

Source: The Worth of Women: their Nobility and Superiority to Men

Gynarchy by proxy

“Gynarchy refers to government by women, or women-centered government.”

~Cassandra Langer

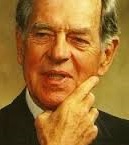

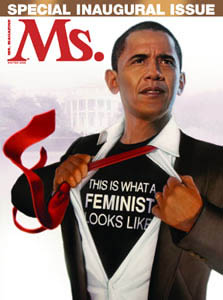

In his groundbreaking work The Myth of Male Power, Warren Farrell explains how men have traditionally striven to institute women-centered government by acting as women’s proxy agents in the political sphere. This behaviour, explains Farrell, is based on the chivalrous tradition of male servicing of women’s needs. The following are passages from Farrell’s book explaining how gynarchy by proxy works:

“Doesn’t the fact that almost all legislators are men prove that men are in charge and can choose when to and when not to look out for women’s interests? Theoretically, yes. But practically speaking the American legal system cannot be separated from the voter. And in the 1992 Presidential election , 54 percent of the voters were female, 46 percent were male. (Women’s votes outnumber men’s by more than 7 million). Overall, a legislator is to a voter what a chauffeur is to the employer – both look like they’re in charge but both can be fired if they don’t go where they’re told. When legislators do not appear to be protecting women, it is almost always because women differ on what constitutes protection. (For example, women voted almost equally for Republicans and Democrats during the combination of the four presidential elections prior to Clinton).

“The Government as Substitute Husband did for women what labor unions still have not accomplished for men. And men pay dues for labor unions; the taxpayer pays the dues for feminism. Feminism and government soon become taxpayer-supported women’s unions. The political parties have become like two parents in a custody battle, each vying for their daughter’s love by promising to do the most for her. How destructive to women is this? We have restricted humans from giving “free” food to bears and dolphins because we know that such feeding would make them dependent and lead to their extinction. But when it comes to our own species, we have difficulty seeing the connection between short-term kindness and long-term cruelty: we give women money to have more children, making them more dependent with each child and discouraging them from developing the tools to fend for themselves. The real discrimination against women, then, is “free feeding.”

Ironically, when political parties or parents compete for females’ love by competing to give it, the result is not gratitude but entitlement. And the result should not be gratitude, because the political party, like the needy parent, becomes unconsciously dependent on keeping the female dependent. Which turns the female into “the other” — the person given to, not the equal participant. In the process, it fails to do what is every parent’s and every political party’s job — to raise an adult, not maintain a child.

But here’s the rub. When the entitled child has the majority of the votes, the issue is no longer whether we have a patriarchy or a matriarchy — we get a victimarchy. And the female-as-child genuinely feels like a victim because she never learns how to obtain for herself everything she learns to expect. Well, she learns how to obtain it for herself by saying “it’s a woman’s right” — but she doesn’t feel the mastery that comes with a lifetime of doing it for herself. And even when a quota includes her in the decision-making process, she still feels angry at the “male dominated government” because she feels both the condescension of being given “equality” and the contradiction of being given equality. She is still “the other.” So, with the majority of the votes, she is both controlling the system and angry at the system.”

But here’s the rub. When the entitled child has the majority of the votes, the issue is no longer whether we have a patriarchy or a matriarchy — we get a victimarchy. And the female-as-child genuinely feels like a victim because she never learns how to obtain for herself everything she learns to expect. Well, she learns how to obtain it for herself by saying “it’s a woman’s right” — but she doesn’t feel the mastery that comes with a lifetime of doing it for herself. And even when a quota includes her in the decision-making process, she still feels angry at the “male dominated government” because she feels both the condescension of being given “equality” and the contradiction of being given equality. She is still “the other.” So, with the majority of the votes, she is both controlling the system and angry at the system.”

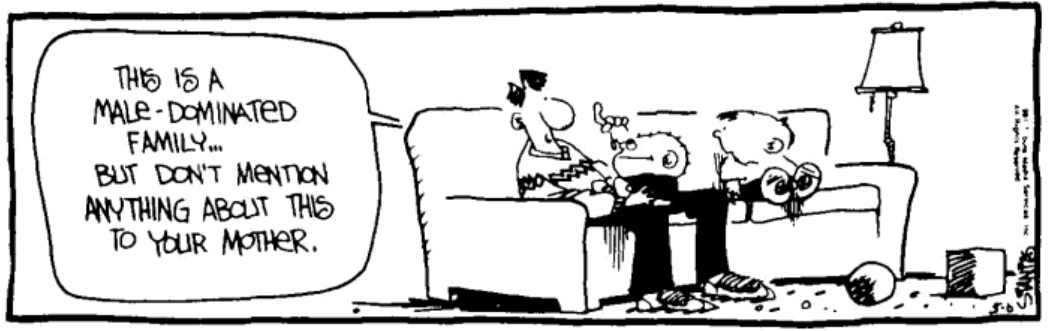

Gynarchy in the home and family:

“When we say we lived in a patriarchy, we think of living under a male dominated government or power structure. We forget that the family had at least as much power as the government in people’s everyday life, and that the family was female dominated. We forget that it too was a power structure. As we have seen, though, almost every woman had a primary role in the female-dominated family structure; only a small percentage of men had a primary role in the male-dominated governmental and religious structures. Although a man’s home was more likely to be his mortgage than his castle, it has always been a characteristic of men that they give lip service to their dominance even as another part of them is aware of their subservience…”

Petticoat government (1702)

Source: Petticoat-Government in a Letter to the Court Lords by the Author of the Post-Angel (1702)

The Spirit of Chivalry, by Sir Walter Scott (1818)

The following excerpts describing gynocentric-chivalry are taken from Sir Walter Scott’s 1818 essay in the volume Essays on Chivalry, Romance, and the Drama

* * *

The main ingredient in the spirit of Chivalry, second in force only to the religious zeal of its professors, and frequently predominating over it, was a devotion to the female sex, and particularly to her whom each knight selected as the chief object of his affection, of a nature so extravagant and unbounded as to approach to a sort of idolatry. The original source of this sentiment is to be found, like that of Chivalry itself, in the Customs and habits of the northern tribes who possessed, even in their rudest state, so many honourable and manly distinctions, over all the other nations in the same stage of society. The chaste and temperate habits of these youth, and the opinion that it was dishonourable to hold sexual intercourse until the twentieth year was attained, was in the highest degree favourable not only to the morals and health of the ancient Germans, but must have contributed greatly to place their females in that dignified and respectable rank which they held in society.

____________________________

Amid the various duties of knighthood, that of protecting the female sex, respecting their persons, and redressing their wrongs, becoming the champion of their cause, and the chastiser of those by whom they were injured, was represented as one of the principal objects of the institution. Their oath bound the new-made knights to defend the cause of all women without exception ; and the most pressing way of conjuring them to grant a boon was to implore it in the name of God and the ladies. The cause of a distressed lady was, in many instances, preferable to that even of the country to which the knight belonged. Thus, the Captal de Buche, though an English subject, did not hesitate to unite his troops with those of the Comte de Foix, to relieve the ladies in a French town, where they were besieged and threatened with violence by the insurgent peasantry.

The looks, the words, the sign of a lady, were accounted to- make knights at time of need perform double their usual deeds of strength and valour. At tournaments and in combats, the voices of the ladies were heard like those of the German females in former battles, calling on the knights to remember their fame, and exert themselves to the uttermost. “Think, gentle knights,” was their cry, “upon the wool of your breasts, the nerve of your arms, the love you cherish in your hearts, and do valiantly for ladies behold you.” The corresponding shouts of the combatants were, “Love of ladies! Death of warriors! On, valiant knights, for you fight under fair eyes? Where the honour or love of a lady was at stake, the fairest prize was held out to the victorious knight, and champion from every quarter were sure to hasten to combat in a cause so popular. Chaucer, when he describes the assembly of the knights who came with Arcite and Palemon to fight for the love of the fair Emilie, describes the manners of his age in the following lines;

“For every knight that loved chivalry,

And would his thankes have a passant name,

Hath pray’d that he might ben of that game,

And well was him that thereto chusen was.

For if there fell to-morrow such a case,

Ye knowen well that every lusty knight

That loveth par amour, and hath his might,

Were it in Engellande, or elleswhere,

They wold hir thanked willen to be there.

To fight for a lady! Ah! Benedicite,

It were a lusty sight for to see.”

It is needless to multiply quotations on a subject so trite and well known. The defence of the female sex in general, the regard due to their honour, the subservience paid to their commands, the reverent awe and courtesy, which, in their presence, forbear all unseemly words and actions, were so blended with the institution of Chivalry as to form its very essence. But it was not enough that the “very perfect, gentle knight,” should reverence the fair sex in general. It was essential to his character that he should select, as his proper choice, “a lady and a love,” to be the polar star of his thoughts, the mistress of his affections, and the directress of his actions. In her service, he was to observe the duties of loyalty, faith, secrecy, and reverence. Without such an empress of his heart, a knight, in the phrase of the times, was a ship without a rudder, a horse without a bridle, a sword without a hilt ; a being, in short, devoid of that ruling guidance and intelligence, which ought to inspire his bravery, and direct his actions. The least dishonest thought or action was, according to her doctrine, sufficient to forfeit the chivalrous lover the favour of his lady.

It seems, however, that the greater part of her charge concerning incontinence is levelled against such as haunted the receptacles of open vice ; and that she reserved an exception (of which, in the course of the history, she made liberal use) in favour of the intercourse which, in all love, honour, and secrecy, might take place, when the favoured and faithful knight had obtained, by long service, the boon of amorous mercy from the lady whom he loved par amours.In these extracts are painted the actual manners of the age of Chivalry. The necessity of the perfect knight having a mistress, whom he loved par amours, the duty of dedicating his time to obey her commands, however capricious, and his strength to execute extravagant feats of valour, which might redound to her praise, –for all that was done for her sake, and under her auspices, was counted her merit, as the victories of their generals were ascribed to the Roman Emperors— was not a whit less necessary to complete the character of a good knight.

__________________________

On such occasions, the favoured knight, as he wore the colours and badge of the lady of his affections, usually exerted his ingenuity in inventing some device or cognisance which might express their love, either openly, as boasting of it in the eye of the world, or in such mysterious mode of indication as should only be understood by the beloved person if circumstances did not permit an avowal of his passion. The ladies, bound as they were in honour to requite the passion of their knights, were wont, on such occasions, to dignify them by the present of a scarf, ribbon, or glove, which was to be worn in the press of battle and tournament. These marks of favour they displayed on their helmets, and they were accounted the best incentives to deeds of valour. The custom appears to have prevailed in France to a late period, though polluted with the grossness so often mixed with the affected refinement and gallantry of that nation.

Sometimes the ladies, in conferring these tokens of their favour, saddled the knights with the most extravagant and severe conditions. But the lover had his advantage in such cases, that if he ventured to vencounter the hazard imposed, and chanced to survive it, he had, according to the fashion of the age, the right of exacting, from the lady, favours corresponding in importance.

The annals of Chivalry abound with stories of cruel and cold fair ones, who subjected their lovers to extremes of danger, in hopes that they might get rid of their addresses, but were, upon their unexpected success, caught in their own snare, and, as ladies who would not have their name made the theme of reproach by every minstrel, were compelled to recompense the deeds which their champion had achieved in their name.

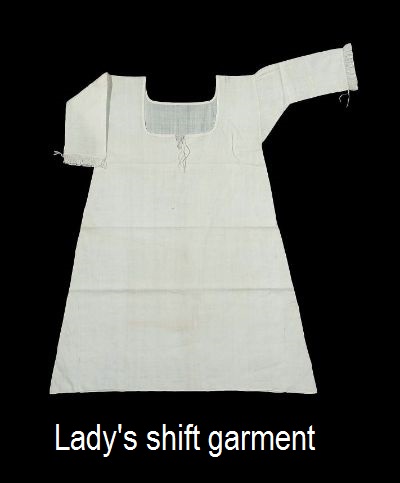

There are instances in which the lover used his right of reprisals with some rigour, as in the well-known fabliau of the three knights and the shift; in which a lady proposes to her three lovers, successively, the task of entering, unarmed, into the mêlée of a tournament, arrayed only in one of her shift. The perilous proposal is declined by two of the knights and accepted by the third, who thrusts himself, in the unprotected state required, into all the hazards of the tournament, sustains many wounds, and carries off the prize of the day.

On the next day the husband of the lady (for she was married) was to give a superb banquet to the knights and nobles who had attended the tourney. The wounded victor sends the shift back to its owner, with his request, that she would wear it over her rich dress on this solemn occasion, soiled and torn as it was, and stained all over with the blood of its late wearer. The lady did not hesitate to comply, declaring, that she regarded this shift, stained with the blood of her “fair friend, as more precious than if it were of the most costly materials.” Jaques de Basin, the minstrel who relates this curious tale, is at a loss to say whether the palm of true love should be given to the knight or to the lady on this remarkable occasion. The husband, he assures us, had the good sense to seem to perceive nothing uncommon in the singular vestment with which his lady was attired, and the rest of the good company highly admired her courageous requital of the knight’s gallantry. It was the especial pride of each distinguished champion, to maintain, against all others, the superior worth, beauty, and accomplishments of his lady; to bear her picture from court to court, and support, with lance and sword, her superiority to all other dames, abroad or at home. To break a spear for the love of their ladies, was a challenge courteously given, and gently accepted, among all true followers of Chivalry, and history and romance are alike filled with the tilts and tournaments which took place upon this argument, which was ever ready and ever acceptable. Indeed, whatever the subject of the tournament had been, the lists were never closed until a solemn course had been made in honour of the ladies.

There were knights yet more adventurous, who sought to distinguish themselves by singular and uncommon feats of arms in honour of their mistresses; and such was usually the cause of the whimsical and extravagant vows of arms which we have subsequently to notice. To combat against extravagant odds, to fight amid the press of armed knights without some essential part of their armour, to do some deed of audacious valour in face of friend and foe, were the services by which the knights strove to recommend themselves, or which their mistresses (very justly so called) imposed on them as proofs of their affection.

Sometimes the patience of the lover was worn out by the cold-hearted vanity which thrust him on such perilous enterprises. At the court of one of the German emperors, while some ladies and gallants of the court were looking into a den where two lions were confined, one of them purposely let her glove fall within the palisade which enclosed the animals, and commanded her lover, as a true knight, to fetch it out to her. He did not hesitate to obey, jumped over the enclosure ; threw his mantle towards the animals as they sprung at him; snatched up the glove, and regained the outside of the palisade. But when in safety, he proclaimed aloud, that what he had achieved was done for the sake of his own reputation, and not for that of a false lady, who could, for her sport and cold-blooded vanity, force a brave man on a duel so desperate. And, with the applause of all that were present, renounced her love for ever. This, however, was an uncommon circumstance. In general, the lady was supposed to have her lover’s character as much at heart as her own, and to mean by pushing him upon enterprises of hazard give him an opportunity of meriting her good graces, which she could not with honour confer upon one undistinguished by deeds of chivalry.

Source:Essays on Chivalry, Romance, and the Drama, by Sir Walter Scott