1. Introduction: A New Language for a Broken Landscape

We live in a time when relationships are harder to navigate than ever. Expectations are unclear, commitments are unstable, and traditional frameworks have either collapsed or been pathologized. In the middle of this mess, something new has emerged—something grounded, mature, and restorative. It’s called the Gold Pill.

The Gold Pill is not a fantasy or a reaction, but a return to realism. It offers men and women a way to understand relationships not just through feelings or resentment, but through value, structure, and mutual respect. It’s a mindset for those who want a partnership that lasts, not just sparks that fade.

2. What Is the Gold Pill?

The Gold Pill is a philosophy of relationships rooted in ancient wisdom, updated for the modern world. It’s a response to the extremes of the current dating culture—especially those promoted in the Manosphere—and offers a third path: neither cynical nor delusional.

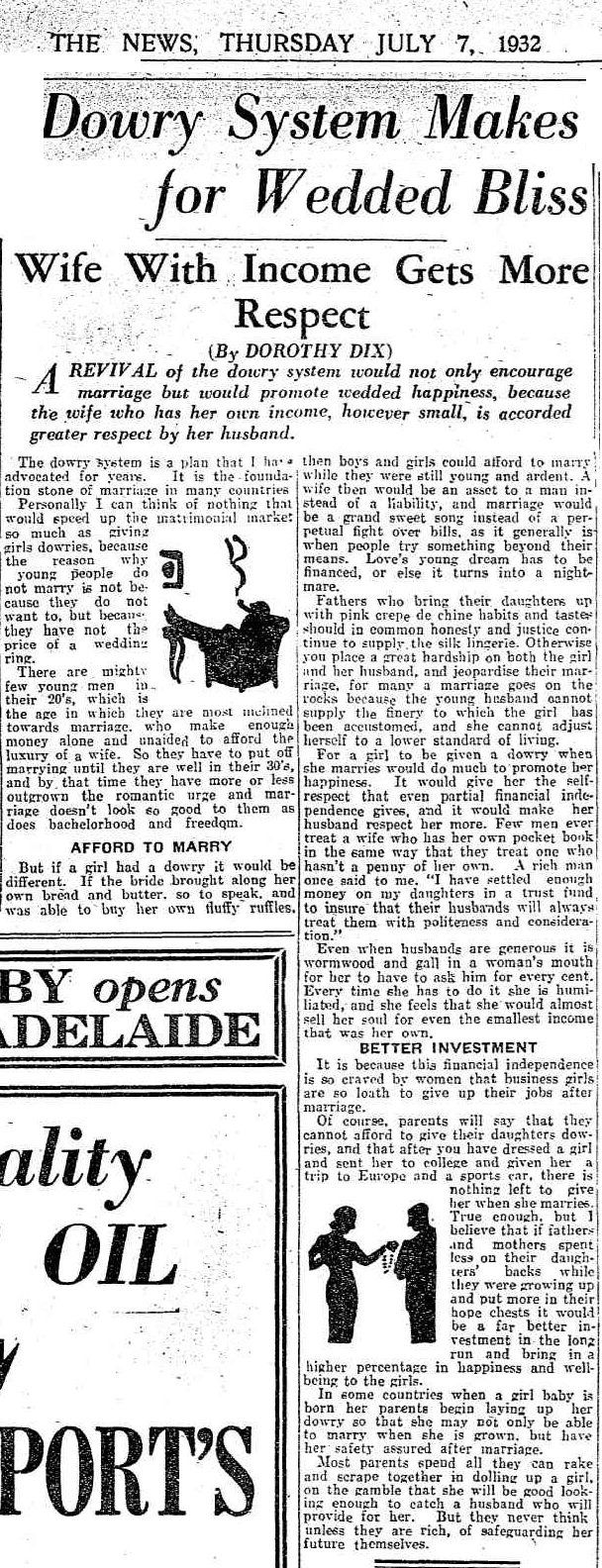

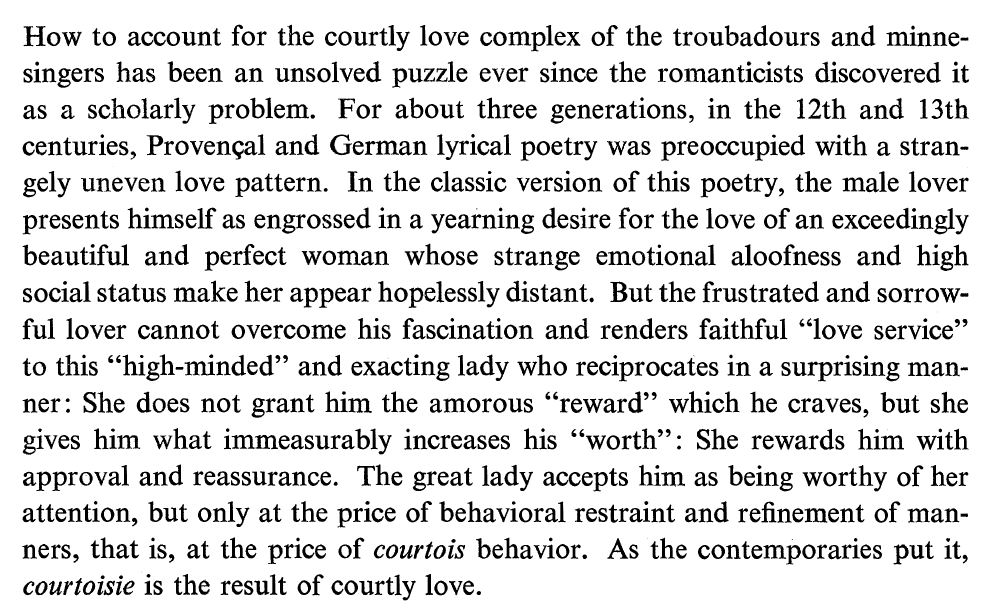

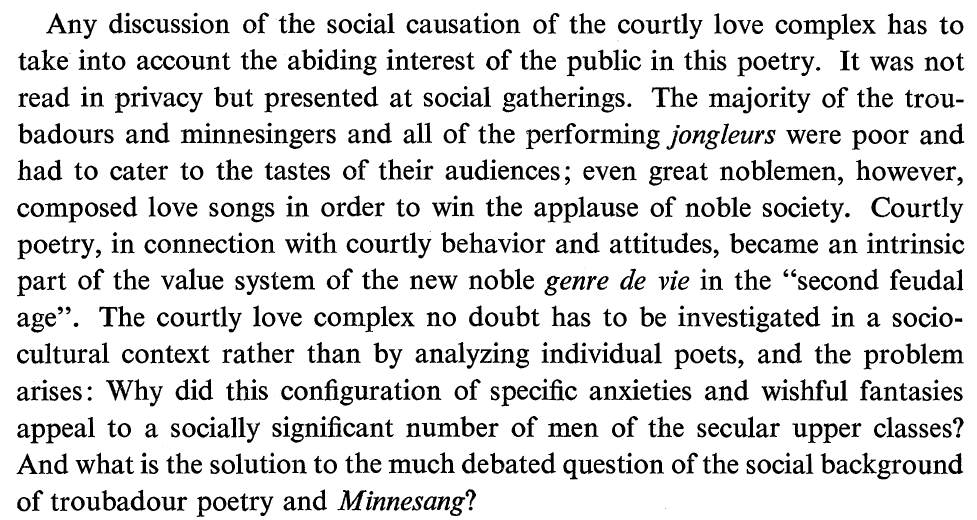

At its heart, the Gold Pill insists that love is not free. Historically, love was structured—backed by family negotiations, community standards, and clear reciprocal obligations. That structure, however imperfect, kept relationships sustainable.

Today, that structure has been replaced by something far flimsier: feelings, vibes, and social media approval. The Gold Pill doesn’t reject love. It simply warns that romance without reciprocity becomes a trap. What was once known as dowry, alliance, and mutual obligation has been degraded into performative gestures and one-sided devotion. Men now routinely pay for virtual attention on platforms like OnlyFans, and pledge lifelong devotion in the form of marriage proposals… often to women who offer little, if any, meaningful reciprocity. The Gold Pill reclaims those lost truths and reframes them in a way that is practical, fair, and deeply human.

Unlike the optimism of pop psychology, which often suggests that love will simply arrive if we work on ourselves, the Gold Pill recognizes that love is a social structure, not just a personal feeling. It must be cultivated, negotiated, and honored by both partners.

3. The Philosophical Backbone: Key Tenets of the Gold Pill

The Gold Pill Credo (by iTrebor) lays out its philosophy with clarity:

• Love is not unconditional: It has always required structure and contribution.

• The dowry system never disappeared: It changed form and became an unspoken expectation on men.

• Provision without reciprocity is exploitation: Giving without return is not noble—it is servitude.

• Romance is not a foundation: Feelings follow structure, not the other way around.

• Men have value by default: Worth is not earned through endless labor or submission.

• Fairness is the foundation of respect: Without balance, love decays into resentment.

This philosophy rejects both the idealism of the Blue Pill and the nihilism of the Black Pill. It avoids the rage of the Red Pill and the illusions of the pickup artist world. Instead, it studies history, incentives, and human nature. The goal is not domination or detachment—but durable connection.

4. Context: The Manosphere and Its Fragmented Pillars

To understand the Gold Pill, it helps to know the world it emerged from: the Manosphere. This loosely connected online ecosystem explores men’s issues, dating dynamics, masculinity, and society’s changing expectations of men.

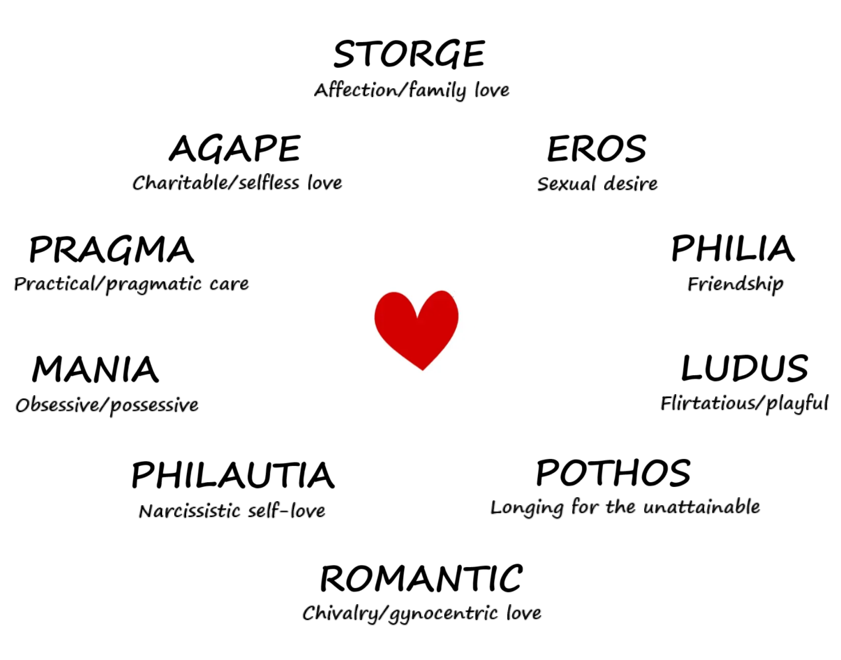

Over time, the Manosphere has splintered into camps:

• Red Pill: Rooted in evolutionary psychology and social critique. Its main insight is that many romantic ideals are false, but it often falls into bitterness and manipulation.

• Blue Pill: The mainstream narrative. It believes in love as an organic, magical outcome if you’re a good enough person. It’s deeply idealistic—and often blind to modern realities.

• Black Pill: A fatalistic view that believes looks and status are all that matter. Often associated with incels, it sees relationships as rigged beyond redemption.

• Pickup Artists (PUAs): Focused on tactics for seduction. Often transactional and performance-based.

• MGTOW (Men Going Their Own Way): A disengagement philosophy where men distance themselves from traditional relationships—especially marriage—to protect their peace, autonomy, and long-term well-being. While many opt out entirely, some maintain selective relationships on their own terms. At its core, MGTOW resists systems seen as exploitative or one-sided.

• Men’s Rights Activists (MRAs): Focus on legal and institutional bias against men, such as in family courts and domestic violence law.

• Christ Pill: A smaller but growing movement that believes a return to traditional Christian morality is the solution to modern relationship chaos.

• Passport Bros: Men who leave Western dating markets in search of relationships abroad where they feel more respected or appreciated.

These all offer pieces of the puzzle—but often fail to deliver a vision that is both honest and hopeful. That’s where the Gold Pill comes in.

5. Origins and Influences: Where the Gold Pill Comes From

The Gold Pill grew organically from deep, ongoing conversations between creators, scholars, and thinkers trying to make sense of modern relationships. Its central figure is Shah, creator of the ThisIsShah stream on YouTube. Shah’s work draws on everything from child support, men’s issues, history, anthropology and economics to personal testimony and religious tradition.

The term “Gold Pill” itself was coined by Shah’s friend iTrebor during a Saturday Night Stream on May 10, 2025. Since then, the idea has taken on a life of its own.

Other influential voices include:

• Jon, creator of the ItsComplicated YouTube channel, known for his street interviews revealing public confusion around relationship norms and gender roles.

• Paul Elam, founder of A Voice for Men, a key figure in the men’s rights movement.

• Peter Wright, scholar and historian on gender norms and gynocentric culture, is the founder of Gynocentrism.com, a long-running blog documenting the history and impact of female-centered social structures.

• Stephen Baskerville, political scientist focusing on family law and fatherhood.

• The broader community of ThisIsShah stream participants, who bring lived experience, academic rigor, and honest dialogue to the table.

These thinkers, along with countless everyday men, are shaping a new paradigm—one where men no longer self-sacrifice to be accepted but instead build on mutual respect.

6. Reclaiming the Dowry: Ancient Tools for Modern Partnership

One of the most striking contributions of the Gold Pill is its re-evaluation of the dowry.

Most people today misunderstand dowries as primitive or patriarchal. But in truth, the dowry system often served as a stabilizing mechanism. It forced both families to take marriage seriously, provided the couple with resources to start their life, and ensured that the union was equitable. The dowry was not a payment for a bride—it was an investment in a future.

In many cultures, it balanced hypergamy, reinforced mutual obligations, and allowed structured negotiations. Where it functioned well, it gave young couples a better shot at long-term success than today’s vibe-based dating economy.

The Gold Pill revives this understanding—not to copy it literally, but to translate its principles for today. Structure. Reciprocity. Shared mission. These are the real currencies of lasting relationships.

7. Conclusion: From Fragmentation to Foundation

The Gold Pill isn’t a reaction—it’s a reconstruction. It doesn’t exist to fight women or rage against the system. It exists because men and women both deserve better than what we’ve been sold.

In a world of romantic confusion, the Gold Pill offers clarity.

In a world of transactional performance, it offers structure.

In a world of silent burnout, it offers reciprocity.

Whether you’re a man trying to find your footing, or a woman seeking partnership that feels truly mutual, the Gold Pill invites you to rebuild—not from fantasy, but from value. From intention. From wisdom.

We don’t retreat. We don’t chase. We build.

And this time, we build with gold.

_______________________________________________

Epilogue: My Gold Pill Moment

For years, I navigated the world of dating with a sense of confusion and frustration. Despite my best efforts to be a supportive and understanding partner, relationships often left me feeling unappreciated and emotionally drained.

It wasn’t until I discovered Shah’s content that I began to see things differently. His insights into the dynamics of modern relationships and the importance of mutual respect resonated deeply with me. I realized that I had been operating under misguided assumptions, believing that self-sacrifice and constant validation were the keys to a successful partnership.

This revelation was both liberating and empowering. I started to approach relationships with a renewed sense of self-worth, seeking connections that were balanced, respectful, and grounded in mutual appreciation. The Gold Pill philosophy didn’t just change my perspective—it transformed my life.