The following piece written in 1959 by Joseph Campbell, scholar of religion and mythology, proposes Supernormal Stimuli as the functional purpose of mythological imagery. – PW

_____________________

The Supernormal Sign Stimulus

by Joseph Campbell

One further lesson may be taken from animals. There is a phenomenon known to the students of animal behavior as the “supernormal sign stimulus,” which has never been considered, as far as I know, in relation either to art and poetry or to myth; yet which, in the end, may be our surest guide to the seat of their force, and to an appreciation of their function in the quickening of the human dream of life.

“The Innate Releasing Mechanism (IRM),” Tinbergen declares, “usually seems to correspond more or less with the properties of the environmental object or situation at which the reaction is aimed. . . . However, close study of IRMs reveals the remarkable fact that it is sometimes possible to offer stimulus situations that are even more effective than the natural situation. In other words, the natural situation is not always optimal.” 11

It was found, for instance, that the male of a certain butterfly known as the grayling (Eumenis semele), which assumes the initiative in mating by pursuing a passing female in flight, generally prefers females of darker hue to those of lighter—and to such a degree that if a model of even darker hue than anything known in nature is presented, the sexually motivated male will pursue it in preference even to the darkest female of the species.

“Here we find,” writes Professor Portmann, in comment, “an ‘inclination’ that is not satisfied in nature, but which perhaps, one day, if inheritable darker mutations should appear, would play a role in the selection of mating partners. Who knows whether such anticipations of particular sign stimuli may not play their part in the support and furthering of new variants, inasmuch as they may represent one of the factors in the process of selection that determines the direction of evolution?” 12

Obviously the human female, with her talent for play, recognized many millenniums ago the power of the supernormal sign stimulus: cosmetics for the heightening of the lines of her eyes have been found among the earliest remains of the Neolithic Age. And from there to an appreciation of the force of ritualization, hieratic art, masks, gladiatorial vestments, kingly robes, and every other humanly conceived and realized improvement of nature, is but a step—or a natural series of steps.

Evidence will appear, in the course of our natural history of the gods, of the gods themselves as supernormal sign stimuli; of the ritual forms deriving from their supernatural inspiration acting as catalysts to convert men into gods; and of civilization—this new environment of man that has grown from his own interior and has pressed back the bounds of nature as far as the moon—as a distillate of ritual, and consequently of the gods: that is to say, as an organization of supernormal sign stimuli playing on a set of IRMs never met by nature and yet most properly nature’s own, inasmuch as man is her son.

But for the present, it suffices to remark that one cannot assume out of hand that simply because a certain culturally developed sign stimulus appeared late in the course of history, man’s response to it must represent a learned reaction. The reaction may be, in fact, spontaneous, though never shown before. For the creative imagination may have released precisely here one of those innate “inclinations” of the human organism that have nowhere been fully matched by nature. Hence, not only the ritual arts and the development from them of the archaic civilizations, but also—and even more richly—the later shattering of those arts by the modern arrows of man’s flight beyond his own highest dream, would perhaps best be interpreted psychologically, as a history of the supernormal sign stimuli that have released—to our own fright, joy, and amazement—the deepest secrets of our being. Indeed, the depths of the mystery of our subject—which are the depths not only of man but of the living world—have not been plumbed.

In sum, then: Within the field of the study of animal behavior— which is the only area in which controlled experiments have made it possible to arrive at dependable conclusions in the observation of instinct—two orders of innate releasing mechanisms have been identified, namely, the stereotyped, and the open, subject to imprint. In the case of the first, a precise lock-key relationship exists between the inner readiness of the nervous system and the external sign stimulus triggering response; so that, if there exist in the human inheritance many—or even any—IRMs of this order, we may justly speak of “inherited images” in the psyche. The mere fact that no one can yet explain how such lock-key relationships are established does not invalidate the observation of their existence: no one knows how the hawk got into the nervous system of our barnyard fowl, yet numerous tests have shown it to be, de facto, there. However, the human psyche has not yet been, to any great extent, satisfactorily tested for such stereotypes, and so, I am afraid, pending further study, we must simply admit that we do not know how far the principle of the inherited image can be carried when interpreting mythological universals. It is no less premature to deny its possibility than to announce it as anything more than a considered opinion.

Nor are we ready, yet, to say whether the obvious, and sometimes very striking, physical differences of the human races represent significant variations of their innate releasing mechanisms. Among the animals such differences do exist—in fact, changes in the IRMs of the major instincts appear to be among the first things affected by mutation.

For example, as Tinbergen observes:

The herring gull (Larus argentatus) and the lesser black-backed gull (L. fuscus) in north-western Europe are considered to be extremely diverged geographical races of one species, which, having developed by geographical isolation, have come into contact again by expansion of their ranges. The two forms show many differences in behavior; L. fuscus is a definite migrant, traveling to south-westem Europe in autumn, whereas L. argentatus is of a much more resident habit. L. fuscus is much more a bird of the open sea than L. argentatus. The breeding-seasons are different. One behavior difference is specially interesting. Both forms have two alarm calls, one expressing alarm of relatively low intensity, the other indicative of extreme alarm. L. argentatus gives the high-intensity alarm call much more rarely than L. fuscus. The result is that most disturbances are reacted to differently by the two forms. When a human intruder enters a mixed colony, the herring gulls will almost always utter the low-intensity call, while L. fuscus utters the high-intensity call. This difference, based upon a shift of degree in the threshold of alarm calls, gives the impression of a qualitative difference in the alarm calls of the two forms, such as might well lead to the total disappearance of one call in one species, of the other in the second species, and thus result in a qualitative difference in the motor-equipment. Apart from this difference in threshold, there is a difference in the pitch of each call.13

Between the various human races differences have been noted that suggest psychological as well as merely physiological variation; differences, for example, in their rates of maturing, as Géza Róheim has indicated in his vigorous work on Psychoanalysis and Anthropology.1* However, it is still far from legitimate, on the

basis of the mere scraps of controlled observation that have been recorded, to make any such broad generalizations about intellectual ability and moral character as are common in discussions of this subject. Furthermore, within the human species there is such broad variation of innate capacity from individual to individual that generalizations on a racial basis lose much of their point.

In other words, the whole question of the innate stereotypes of the species Homo sapiens is still wide open. Objective and promising studies have been commenced, but they have not yet progressed very far. An interesting series of experiments by E. Kaila,15 and R. A. Spitz and K. M. Wolf,16 has shown that between the ages of three and six months the infant reacts with a smile to the appearance of a human face; and by fashioning masks omitting certain of the details of the normal human countenance, the observers were able to establish the fact that in order to evoke response the face had to have two eyes (one-eyed, asymmetrical masks did not work), a smooth forehead (wrinkled foreheads produced no smile), and a nose. Curiously, the mouth could be omitted; the smile, therefore, was not an imitation. The face had to be in some movement and seen from the front. Moreover, nothing else—not even a toy—would evoke this early infant smile. Following the sixth month, a distinction began to be made between familiar and unfamiliar, friendly and unfriendly faces. The richness of the child’s experience of its social environment having already increased, the innate releasing mechanism had been altered by impressions from the outer world, and the situation had changed.

It has been remarked that in certain primitive Australian rock paintings of ancestral figures the mouths are omitted, and that a significant number of very early, paleolithic female figurines also lack the mouth. How far one can presume to carry these suggestions toward the conclusion that there is a “parental image” in the central nervous structure of the human infant, however, we cannot say. As Professor Portmann has pointed out: “Since the effect of this form on the infant can be demonstrated with certainty only from the third month, the question remains open as to whether the central nervous structure that makes possible the recognition of the human countenance and the social response of the smile is of the open, i.e. imprinted, type, or entirely innate. All of the indices available to us speak for a largely inherited configuration; and yet, the question remains open.”17

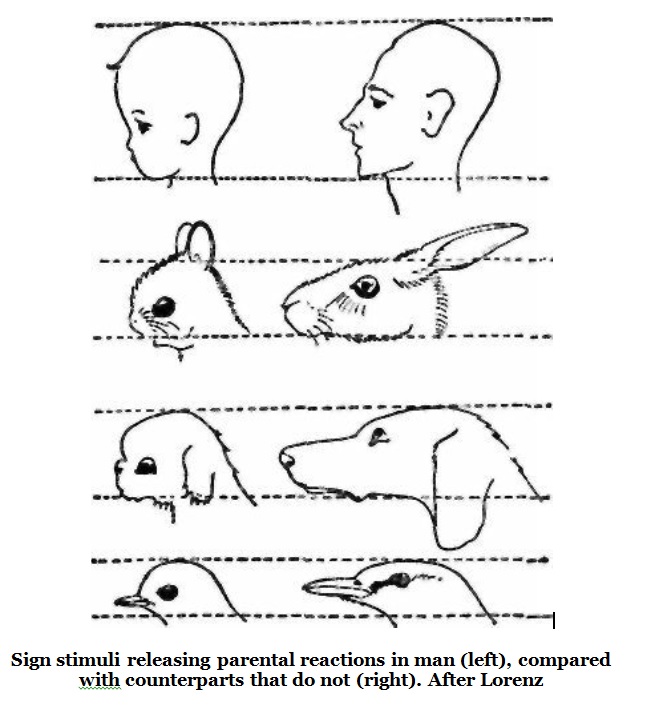

How much more open, then, the question broached by Professor Lorenz in his paper on “The Innate Forms of Human Experience”: 18 the question of the parental response evoked in the adult by the sign stimuli provided by the human baby! The figure tells the story—as far as it goes.

And finally, it must be noted that there is no consensus among students of the subject even as to what categories of appetite may be regarded as instinctive in the human species. Professor Tinbergen, speaking for the animal world, has named sleep and food-seeking; so also, in many species, flight from danger, fighting in self-defense, and a number of activities functionally related to the reproductive urge, as, for example, sexual fighting and rivalry, courtship, mating, and parental behavior (nest-building, protection of the young, etc.). The list greatly varies, however, from species to species; and how much of it can be carried over into the human sphere is not yet known. Tentatively, it might reasonably be supposed that food-seeking, sleep, self-protection, courtship and mating, and some of the activities of parenthood should be instinctive. But the question—as we have seen—remains open as to what precisely are the sign stimuli that generally trigger these activities in man, or whether any of the stimuli can be said to be as immediately known to the human interior as the hawk to the chick. We do not, therefore, speak of inherited images in the following pages.

The concept of the sign stimulus as an energy-releasing and -directing image clarifies, however, the difference between literary metaphor, which is addressed to the intellect, and mythology, which is aimed primarily at the central excitatory mechanisms (CEMs) and innate releasing mechanisms (IRMs) of the whole person. According to this view, a functioning mythology can be defined as a corpus of culturally maintained sign stimuli fostering the development and activation of a specific type, or constellation of types, of human life. Furthermore, since we now know that no images have been established unquestionably as innate and that our IRMs are not stereotyped but open, whatever “universals” we may find in our comparative study must be assigned rather to common experience than to endowment; while, on the other hand, even where sign stimuli may differ, it need not follow that the responding IRMs differ too. Our science is to be simultaneously biological and historical throughout, with no distinction between “culturally conditioned” and “instinctive” behavior, since all instinctive human behavior is culturally conditioned, and what is culturally conditioned in us all is instinct: specifically, the CEMs and IRMs of this single species.

Therefore, though respecting the possibility—perhaps the probability—of such a psychologically inspired parallel development of mythological imagery as that suggested by Adolf Bastian’s theory of elementary ideas and C. G. Jung’s of the collective unconscious, we cannot attempt to interpret in such terms any of the remarkable correspondences that will everywhere confront us. On the other hand, however, we must ignore as biologically untenable such sociological theorizing as that represented, for example, by the anthropologist Ralph Linton when he wrote that “a society is a group of biologically distinct and self-contained individuals,” 19 since, indeed, we are a species and not biologically distinct. Our approach is to be, as far as possible, skeptical, historical, and descriptive—and where history fails and something else appears, as in a mirror, darkly, we indicate the considered guesses of the chief authorities in the field and leave the rest to silence, recognizing that in that silence there may be sleeping not only the jungle cry of Dryopithecus, but also a supernormal melody not to be heard for perhaps another million years.

11. Tinbergen, op. cit., p. 44.

12. Adolf Portmann, “Die Bedeutung der Bilder in der lebendigen Energiewandlung,” Eranos-Jahrbuch 1952 (Zurich: Rhein-Verlag, 1953), pp. 333-34.

13. Tinbergen, op. cit., p. 197.

14. Gaza Róheim, Psychoanalysis and Anthropology (New York: International Universities Press, 1950), pp. 403-404.

15. E. Kaila, “Die Reaktionen des Säuglings auf das menschliche Gesicht,” Annales Universitatis Aboensis, Turku, Vol. 17 (1932).

16. R. A. Spitz and K. M. Wolf, “The Smiling Response,” Genetic Psychology Monographs, Vol. 34 (1946).

17. Adolf Portmann, “Das Problem der Urbilder in biologischer Sicht,” Eranos-Jahrbuch 1949 (Zurich: Rhein-Verlag, 1950), p. 426.

18. Konrad Lorenz, “Die angeborenen Formen möglicher Erfahrung,” Zeitschrift der Tierpsychologie, Bd. 5 (1943), pp. 235-409.

19. Ralph Linton, The Study of Man (New York and London: D. Appleton-Century

Company, 1936), p. 108.