Alison Phipps, a Professor of Gender Studies at Sussex University, recently published an essay titled White tears, white rage: Victimhood and (as) violence in mainstream feminism, and more recently a book titled Me, Not You: The Trouble With Mainstream Feminism.

There is much detail in her corpus that I am at odds with, and no doubt much in my work that she too would be at odds with. However, I find her thesis broadly accurate when describing the power of white women’s tears (a tradition I refer to as damseling), along with white men’s symbiotic enmeshment with those tears in the form of “chivalric” protection frequently involving warrantless, exaggerated violence, especially in colonial settings. This compact is aptly referred to by Phipps as “a circuit” between white women’s perceived vulnerabilities and white men’s reactivity on their behalf.

Phipps’ essay is the first from a feminist perspective that positions males and females as conspiring together as a circuitous dyad, a position contrasted with that of most other feminist authors who prefer to lump all power and evil with men, and all goodness with women. Phipps describes the sexual relations contract of white European descendants as malignant and exploitative, and while I do agree with her in certain key respects I find her thesis overly reductive and totalising in its demonization.

The following are a few excerpts from her essay on White Women’s Tears:

“Using #MeToo as a starting point, this paper argues that the cultural power of mainstream white feminism partly derives from the cultural power of white tears. This in turn depends on the dehumanisation of people of colour, who were constructed in colonial ‘race science’ as incapable of complex feeling (Schuller 2018). Colonialism also created a circuit between bourgeois white women’s tears and white men’s rage, often activated by allegations of rape, which operated in the service of economic extraction and exploitation. This circuit endures, abetting the criminal punishment system and the weaponisation of ‘women’s safety’ by the various border regimes of the right. It has especially been utilised by reactionary forms of feminism, which set themselves against sex workers and trans people.

“In an article on #MeToo, Jamilah Lemieux (2017) commented: ‘white women know how to be victims. They know just how to bleed and weep in the public square, they fundamentally understand that they are entitled to sympathy’. Lemieux was not claiming the disclosures of #MeToo were not genuine; she was highlighting the power brought to mainstream feminism by the power of white women’s tears. White-lady tears, to use Cooper’s phrase: bourgeois white women’s tears are the ultimate symbol of femininity, evoking the damsel in distress and the mourning, lamenting women of myth (Phipps 2020, p71), and it is likely that this power is not fully accessible to working class white women, who are often figures of classed disgust (Tyler 2008). While it might date back to the ancients, the power of bourgeois white women’s tears was solidified in the modern colonial period, as ‘women’s protection’ became key to the deadly disciplinary power that maintained racialised and classed regimes of extraction and exploitation.

“The narrative – that reactionary feminists are the real victims but their voices are not being heard – achieves several aims. It disseminates reactionary feminist ideas; it deploys Strategic White Womanhood to avoid accountability; it uses the device of white women’s tears to deny humanity to the Other. Reactionary feminists seize womanhood – and personhood – while sex workers become uncaring ‘happy hookers’ and trans women become shadowy threats. We see the weeping Madonna versus the unfeeling whore. We see the weeping survivor versus the menacing predator. Neither sex workers or trans women are entitled to complex feelings or to claim victimisation on their own behalf.

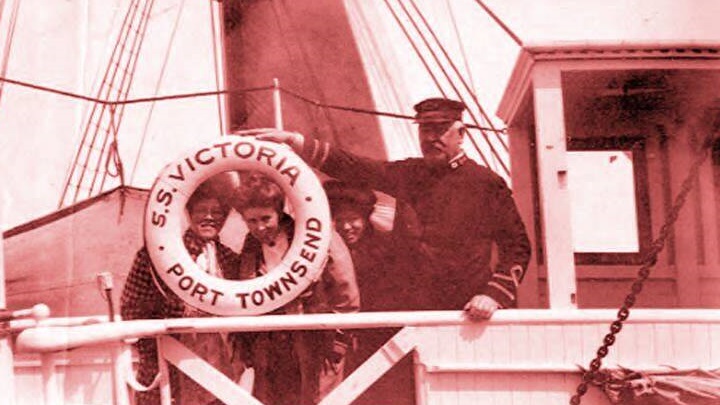

“Structurally, bourgeois white women’s tears support what Sharpe (2016, p16) calls ‘reappearances of the slave ship’: ‘protecting (white) women’ fuels the necropolitics of criminal punishment and the border regimes of Fortress Europe, North America and other parts of the world. These tears enter a world in which marginalised people are disposable, whether they are Black people killed by police, migrants left to starve or drown (Sharpe 2016, pp43-44, 54), or trans people and sex workers (many of them people of colour) disproportionately left to survive outside bourgeois families, communities and the law. The circuit between white women’s tears and white men’s rage means that because we cry, marginalised people can die. As some forms of reactionary feminism exploit this circuit in their engagements with the far right, their narratives of victimhood can themselves be understood as violence. The ship, then, stays afloat: captained by white men, but suspended in a pool of white women’s tears.

__________________________________

See Also:

- Women of Color Feminists Vs. White Feminist Tears

- The Near-Irresistible Lure of Damseling

- Damseling, Chivalry and Courtly Love In The Feminist Tradition

- The Origins Of Damseling

- Two Modes Of Damseling

- Damseling By Women In European Politics

I find it encouraging whenever I see feminists who can acknowledge the part that women (due to their elevated, gynocentric status) play in maintaining the very inequalities they claim to oppose.

A feminist who is prepared to critique feminism objectively (even in part only) is worthy of publication far and wide.

I agree that Phipps’ use of the word “circuit” is well chosen.

Great article.