.

So why is white male+female supremacy a euphemism for white women worship? Because men’s part in the much touted “supremacy” culture is geared largely to the role of servicing white women, a role otherwise known as chivalry or benevolent sexism.

Whether men traditionally called her ma’am, m’lady, madam or some other highfalutin title, the sexual dynamic was always one that positions woman as dominatrix, and the man as submissive liegemen – i.e., it closely resembles sadomasochism. That same sadomasochism has been the centrepiece of the women’s movement in which, for example, early feminists looked down sneeringly on their ebony lessers, claiming as Susan B. Anthony did, “I will cut off this right arm of mine before I will ever work or demand the ballot for the Negro and not the woman,” and which we see continued in the spa and nail shops which have exclusively women of color carving the toejam out of pampered and ’empowered’ white women’s nails.

In her blog post Three Cheers for White Men, medievalist Rachel Fulton Brown waxes poetic about men’s having aided and abetted a culture of worshipping white women — a worship that we know has led to the three evils of misandry, racism, and (white) female narcissism. Here is her post:

1. When white women (see Marie de France and Eleanor of Aquitaine) invented chivalry and courtly love, white men agreed that it was better for knights to spend their time protecting women rather than raping them, and even agreed to write songs for them rather than expecting them to want to have sex with them without being forced.

2. When white men who were celibate (see the canon lawyers and theologians of the twelfth century and thereafter) argued that marriage was a sacrament valid only if both the man and the woman consented, white men exerted themselves to become good husbands rather than expecting women to live as their slaves.

3. When white women (see Christine de Pizan, Mary Wollstonecraft, and the suffragettes) invented feminism, white men supported them (see John Stuart Mill) and even went so far as to vote (because only men could vote at the time) to let them vote, not to mention hiring them as workers and supporting their education.

Fulton Brown copped a lot of flack for praising white men’s chivalry and women’s associated pedestalization. But she was right, even if I would radically differ with her in response to this history — ie. my reaction is one of disgust and rejection of the narcissism and sadomasochism embedded in the heart of the same construct.

Alison Phipps, a Professor of Gender Studies at Sussex University, recently published an essay titled White tears, white rage: Victimhood and (as) violence in mainstream feminism, and more recently a book titled Me, Not You: The Trouble With Mainstream Feminism.

There is much detail in her feminism-inspired corpus that I am at odds with, and no doubt much in my work that she too would be at odds with. However, I find her thesis readable in parts where describing the power of white women’s tears (a tradition I refer to as damseling), along with white men’s symbiotic enmeshment with those tears in the form of “chivalric” protection frequently involving warrantless, exaggerated violence, especially in colonial settings. This compact is aptly referred to by Phipps as “a circuit” between white women’s perceived vulnerabilities and white men’s reactivity on their behalf.

Phipps’ essay is the first from a feminist perspective that positions males and females as conspiring together as a circuitous dyad, a position contrasted with that of most other feminist authors who prefer to lump all power and evil with men, and all goodness with women. Phipps describes the sexual relations contract of white European descendants as malignant and exploitative, and while I do agree with her in certain key respects I find her thesis too reductive and totalising in its demonization.

The following are a few excerpts from her essay on White Women’s Tears:

“Using #MeToo as a starting point, this paper argues that the cultural power of mainstream white feminism partly derives from the cultural power of white tears. This in turn depends on the dehumanisation of people of colour, who were constructed in colonial ‘race science’ as incapable of complex feeling (Schuller 2018). Colonialism also created a circuit between bourgeois white women’s tears and white men’s rage, often activated by allegations of rape, which operated in the service of economic extraction and exploitation. This circuit endures, abetting the criminal punishment system and the weaponisation of ‘women’s safety’ by the various border regimes of the right. It has especially been utilised by reactionary forms of feminism, which set themselves against sex workers and trans people.

“In an article on #MeToo, Jamilah Lemieux (2017) commented: ‘white women know how to be victims. They know just how to bleed and weep in the public square, they fundamentally understand that they are entitled to sympathy’. Lemieux was not claiming the disclosures of #MeToo were not genuine; she was highlighting the power brought to mainstream feminism by the power of white women’s tears. White-lady tears, to use Cooper’s phrase: bourgeois white women’s tears are the ultimate symbol of femininity, evoking the damsel in distress and the mourning, lamenting women of myth (Phipps 2020, p71)… the power of bourgeois white women’s tears was solidified in the modern colonial period, as ‘women’s protection’ became key to the deadly disciplinary power that maintained racialised and classed regimes of extraction and exploitation.

“Structurally, bourgeois white women’s tears support what Sharpe (2016, p16) calls ‘reappearances of the slave ship’: ‘protecting (white) women’ fuels the necropolitics of criminal punishment and the border regimes of Fortress Europe, North America and other parts of the world. These tears enter a world in which marginalised people are disposable, whether they are Black people killed by police, migrants left to starve or drown (Sharpe 2016, pp43-44, 54), or trans people and sex workers (many of them people of colour) disproportionately left to survive outside bourgeois families, communities and the law. The circuit between white women’s tears and white men’s rage means that because we cry, marginalised people can die. As some forms of reactionary feminism exploit this circuit in their engagements with the far right, their narratives of victimhood can themselves be understood as violence. The ship, then, stays afloat: captained by white men, but suspended in a pool of white women’s tears.

After reading Phipps’ essay I’m immediately reminded of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old African American who was lynched in Mississippi in 1955 after being falsely accused of offending a white woman. White men bashed him for offending a white women’s fragile sensibilities (which it turns out was fabricated by the woman) and proceeded to showcase their “chivalry” via the act of torturing and brutally bashing the boy to death. In this one image is captured the scenario painted by Phipps – the compact that would keep white women (and their white male protectors) at the top of the food chain.

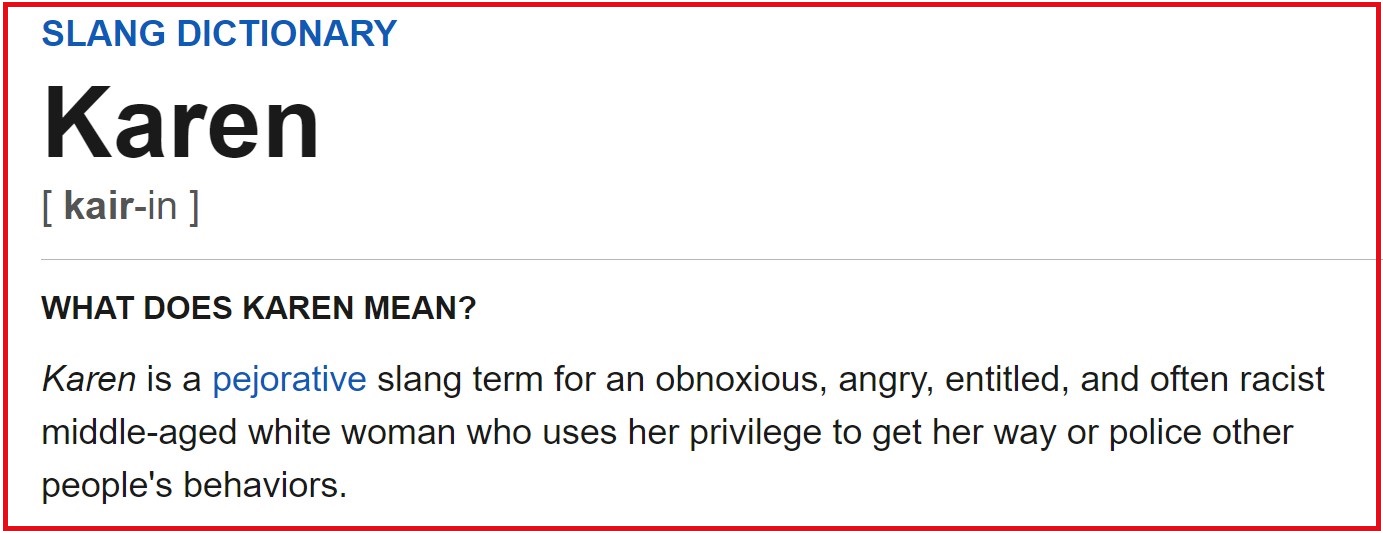

While I won’t join Phipps in her general malignment of white men, the question remains have certain men throughout history showcased white supremacy, sometimes brutally? Yes they have – but to what ends? I’m going to finish with an unpopular conclusion: that white male supremacy, if and when it has existed, has been driven partly, and perhaps even largely, by a desire to protect a culture of white female supremacy. Keep in mind that this conclusion is becoming recognized not only in the rarefied writings of feminists and MRAs, but also among the everyday populace which has in recent times immortalized the ‘Karen’ figure as an example of racist, misandrist, and narcissistic entitlement.

In a time when anti-white racism and critical race theory are gaining momentum (something I do not wish to fuel), keep in mind that some white women are not like that, even if many are. It still pays to follow the dictum of Martin Luther King who encouraged us to look at content of character before color of skin, and by that route we avoid the fallacy of exaggerated class guilt.

See also:

You must log in to post a comment.