Courtly Love (Amour Courtois) refers to an innovative literary genre of poetry of the High Middle Ages (1000-1300 CE) which elevated the position of women in society and established the motifs of the romance genre recognizable in the present day. Courtly love poetry featured a lady, usually married but always in some way inaccessible, who became the object of a noble knight’s devotion, service, and self-sacrifice. Prior to the development of this genre, women appear in medieval literature as secondary characters and their husbands’ or fathers’ possessions; afterward, women feature prominently in literary works as clearly defined individuals in the works of authors such as Chretien de Troyes, Marie de France, John Gower, Geoffrey Chaucer, Christine de Pizan, Dante Alighieri, Giovanni Boccaccio, and Thomas Malory.

Scholars continue to debate whether the literature reflected actual romantic relationships of the upper class of the time or was only a literary conceit. Some scholars have also suggested that the poetry was religious allegory relating to the heresy of the Catharism, which, persecuted by the Church, spread its beliefs through popular poetry while others claim it represents superficial games of the medieval French courts. No consensus has been reached on which of these theories is correct, but scholars do agree that this kind of poetry was unprecedented in medieval Europe and coincided with an idealization of women. The poetry was quite popular in its time, contributed to the development of the Arthurian Legend, and standardized the central concepts of the western ideal of romantic love.

Origin & Name

Courtly love poetry emerged in southern France in the 12th century CE through the work of the troubadours, poet-minstrels who were either retained by a royal court or traveled from town to town. The most famous of the early troubadours (and, according to some scholars, the first) was William IX, Duke of Aquitaine (l. 1071-1127 CE), grandfather of Eleanor of Aquitaine (l. c. 1122-1204 CE). William IX wrote a new kind of poetry, highly sensual, in praise of women and romantic love. William IX and the troubadours who followed him never referred to their work as courtly love poetry or Provencal love poetry – it was simply poetry – but it was unlike any literature produced in Western Europe previously. Scholar Leigh Smith discusses the origin of the name:

The term itself dates back only to 1883 CE when Gaston Paris coined the phrase Amour Courtois to describe Lancelot‘s love for Guinevere in the romance Lancelot (c. 1177 CE) by Chretien de Troyes. Medieval literature employs a variety of terms for this kind of love. In Provencal the word is cortezia (courtliness), French texts use fin amour (refined love), in Latin the term is amor honestus (honorable, reputable love). (Lindahl et. al., 80)

This love praised by the troubadours had nothing to do with marriage as recognized and sanctified by the Church but was extramarital or premarital, freely chosen – as opposed to a marriage which was arranged by one’s social superiors – and passionately pursued. An upper-class medieval marriage was a social contract in which a woman was given to a man to further some agenda of the couple’s parents and involved the conveyance of land. Land equaled power, political prestige, and wealth. The woman, therefore, was little more than a bargaining chip in financial and political transactions.

In the world of courtly love, on the other hand, women were free to choose their own partner and exercised complete control over him. Whether this world reflected a social reality or was simply a romantic literary construct continues to be debated in the present day and central to that question is the figure of Eleanor of Aquitaine.

The Queen of Courtly Love

As with many aspects of the discussion of courtly love, Eleanor’s role in developing the concept remains controversial. Eleanor of Aquitaine was one of the most powerful women of the Middle Ages, wife of Louis VII of France (r. 1137-1180 CE) and Henry II of England (r. 1154-1189 CE), and mother of Marie de Champagne (l. 1145-1198 CE) from her marriage to Louis and Richard I (r. 1189-1199 CE) and King John (r. 1199-1216 CE) from her marriage to Henry. She had eight children in total with Henry II, most of whom would follow her example in patronizing the arts.

Throughout her marriage to Louis VII (1137-1152 CE), Eleanor filled her court with poets and artists. When their marriage was annulled in 1152 CE, Eleanor did the same at her own court in Normandy, where she was especially entertained by the young troubadour Bernard de Ventadour (12th century CE), one of the greatest medieval poets, who would follow her to the court of Henry II in 1152 CE and remain with her there three years, probably as her lover.

Louis VII, after Eleanor’s departure, drove the troubadours from his court as bad influences, and Henry II seems to have had an equally low opinion of the poets. Eleanor admired them, however, and when she separated from Henry II in c. 1170 CE and set up her own court at Poitiers, she again surrounded herself with artists. There is no doubt that she inspired the works of Bernard de Ventadour, but it is likely she did the same for many others and, through her daughter Marie, inspired the greatest and most influential works of courtly love literature.

Chretien de Troyes & Andreas Capellanus

Eleanor’s court at Poitier, c. 1170-1174 CE, is a subject of some controversy among modern-day scholars in that no consensus has been reached as to what went on there. According to some scholars, Marie de Champagne was present while others argue she was not. Some scholars claim that actual courts of love were held there with Eleanor, Marie, and other high-born women presiding over cases in which plaintiffs and defendants would present evidence relating to their romantic relationships; others claim no such courts existed and that any literature suggesting they did is satire.

THE BEST-KNOWN EXAMPLE OF COURTLY LOVE IS LANCELOT’S LOVE FOR GUINEVERE, THE WIFE OF HIS BEST FRIEND & KING, ARTHUR OF BRITAIN.

Whatever happened at Poitiers, Eleanor seems to have established the ground rules for a literary genre – and possibly a social game of sorts – which was then developed by her daughter who was the patroness of the poet Chretien de Troyes (l. c. 1130-1190 CE) and author Andreas Capellanus (12th century CE). Andreas is the author of De Amore (usually translated as The Art of Love) which describes the courts of love presided over by Marie and the others while also serving as a kind of manual in the art of seduction.

The work draws on the earlier satirical Art of Love (Ars Amatoria) of Ovid, published c. 2nd century CE, which presented itself as a serious guide to romantic relationships while actually mocking them and anyone who takes such things seriously. Since Andreas’ work so closely mirrors Ovid’s, some scholars claim that it was written for the same purpose – as satire – while others accept it as a serious guide to navigating the world of courtly love. Andreas set down the four rules of courtly love as, allegedly, derived from Eleanor and Marie’s courts:

- Marriage is no excuse for not loving

- One who is not jealous, cannot love

- No one can be bound by a double love

- Love is always increasing or decreasing

According to these rules, just because one was married did not mean one could not find love outside of that contract; love was expressed most clearly through jealousy which proved one’s devotion; there was only one true love for every individual and no one could honestly claim to love two people the same way; true love was never static but always dynamic, unpredictable, and ultimately unknowable even by those experiencing it because it was initiated and directed by a God of Love (Cupid), not by the lovers themselves. These concepts in Andreas’ prose work were mirrored in Chretien’s poetry.

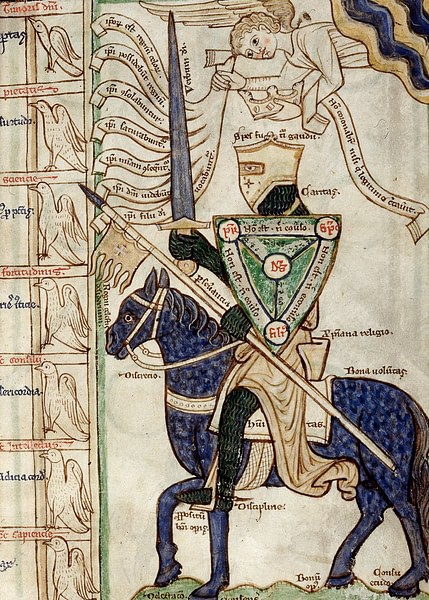

Chretien de Troyes is the poet responsible for some of the best-known aspects of the Arthurian Legend including Lancelot’s affair with Guinevere and the Grail Quest. His works include Erec and Enide, Cliges, Lancelot or the Knight of the Cart, Yvain or the Knight of the Lion, and Percival or the Story of the Grail, all written between c. 1160-1190 CE. Chretien established the central motifs of the genre of courtly love poetry which include:

- A beautiful woman who is inaccessible (either because she is married or imprisoned)

- A noble knight who has sworn to serve her

- A forbidden, passionate love shared by both

- The impossibility or danger of consummating that love

The best-known example of this is Lancelot’s love for Guinevere, the wife of his best friend and king, Arthur of Britain. Lancelot cannot deny his feelings but cannot act on them without betraying Arthur and exposing Guinevere as the unfaithful wife of a noble king. In Malory’s version of the legend, their affair’s exposure is pivotal in destroying the Knights of the Round Table. Another example is the famous story of Tristan and Iseult by Thomas of Britain (c. 1173 CE) in which young Tristan is asked by his uncle Mark to escort Mark’s fiancé Iseult to his castle. Tristan and Iseult fall in love (in some versions because of a love potion accidentally taken) and their betrayal of Mark is the plot point that drives the rest of the story.

Although scholars continue to debate Eleanor of Aquitaine’s role in developing these kinds of stories, even a cursory knowledge of the woman’s life strongly suggests that courtly love poetry was inspired by her. Like the lady character in the poems, Eleanor was never defined by either of her marriages, she always did precisely as she pleased except for the period in which Henry II had her imprisoned, and she inspired devotion in others. Eleanor’s role seems even more prominent if one entertains the theory that courtly love poetry was actually religious allegory depicting the beliefs of the heretical sect of the Cathars.

The Cathars & Courtly Love

The Cathars (from the Greek for “pure ones”) were a religious sect which flourished in southern France – precisely in the regions of the courts of Eleanor and Marie – in the 12th century CE. The sect evolved from the earlier Bogomils of Bulgaria and adherents were popularly known as Albigensians because the town of Albi was their greatest religious center. The Cathars rejected the teachings of the Catholic Church on the grounds they were immoral and the clergy corrupt and hypocritical.

Catharism was dualist – meaning they saw the world as divided between good (the spirit) and evil (the flesh) – and the Church was decidedly on the side of evil as the clergy was more devoted to earthly pleasures than spiritual pursuits, and the dogma emphasized the weight of sin over the hope of redemption. Cathars renounced the world, lived simply, and devoted themselves to helping others. The Cathar clergy were known as perfecti while adherents were called credentes. A third set of people were the sympathizers – those who remained nominally Catholic but supported Cathar communities and protected them from the Church.

The Church suspected both Eleanor and Marie as sympathizers, and this suspicion was strengthened by the actions of Raymond VI, Count of Toulouse (r. 1194-1222 CE), Eleanor’s son-in-law, who was not only a Cathar sympathizer but secretly the Cathar bishop of his region. Raymond was the most ardent defender of the Cathars when the Church finally launched the Albigensian Crusade against Southern France in 1209 CE.

The correlation between Catharism, Eleanor, and courtly love poetry is that this genre seems to appear out of nowhere at the same time Catharism is flourishing and Eleanor is holding her courts. This theory (advanced, primarily, by the scholar Denis de Rougemont in his Love in the Western World), highlights how one of the main tenets of Catharism was recognition of the female principle in the divine which they recognized as the goddess Sophia (wisdom) and how the core of the belief was dualist. The theory then claims that courtly love poetry was an allegory in which the damsel-in-distress was Sophia, held captive by the Catholic Church, and the brave knight was the Cathar whose duty was to liberate her.

The lady symbolized good as spirit – and so the knight could never consummate his love for her – while the marriage she was trapped in, sanctified by the Church, symbolized the evil of the world. This theory is by no means universally accepted but it should be noted that there seems to be a direct correlation between the activities of the troubadours of southern France and the spread of Catharism in the 12th century CE.

A Social Game

Another theory (advanced by scholar Georges Duby, among others), is that courtly love was a medieval social game played by the upper-class in their courts. Duby writes:

Courtly love was a game, an educational game. It was the exact counterpart of the tournament. As at the tournament, whose great popularity coincided with the flourishing of courtly eroticism, in this game the man of noble birth was risking his life and endangering his body in the hope of improving himself, of enhancing his worth, his price, and also of taking his pleasure, capturing his adversary after breaking down her defenses, unseating her, knocking her down and toppling her. Courtly love was a joust. (57-58)

According to this theory, the lady in the tales serves “to stimulate the ardour of young men and to assess the qualities of each wisely and judiciously. The best man was the man who had served her best” (Duby, 62). This theory accounts for the misogynistic elements of courtly love poetry in that the woman is an object to be conquered sexually, not an individual, or is an arbiter of a man’s worth based solely on her status as noble and, again, not because of who she is as a person.

This aspect of the genre, however, may not be so much misogynistic as idealistic. If courtly love was a game invented by women, then woman-as-prize and woman-as-judge would have served the same purpose of elevating their status. Other scholars have pointed out that there were court games played by the upper class well into the Renaissance which would amount to role-playing and that the courts of love Andreas Capellanus describes were not actual courts but simply games the noble ladies created to amuse themselves; the works of Andreas and Chretien and others just added to the enjoyment or provided ground rules. Leigh Smith writes:

As with any game that depends upon the creation of an alternate reality, the fun depends upon all the participants treating that reality with utmost seriousness. Therefore, Andreas’ treatise may be understandable as a guide to being a successful courtier in such a Court of Love. (Lindahl et. al., 82)

The winner in this game would be the knight who exemplified the virtues of chivalry and courtesy in service to his lady. It is possible these games were played over the course of months – and perhaps that is what was happening at Eleanor’s court at Poitiers c. 1170-1174 CE – but the game theory does not explain the passion of the works themselves, the devotion the knight has to the lady, or their enduring popularity. Most importantly, the game theory does not fully explain why, even if women invented the game, they should suddenly be so elevated in this genre in a way no earlier European literature had done.

Conclusion

The genre was considered completely original by scholars of the 19th and 20th centuries CE who, while recognizing the central motif of the elevation of the lady present in some Roman works and the biblical Song of Songs, had little or no knowledge of the literature of ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt. As noted, ‘courtly love’ was coined by French writer Gaston Paris only in 1883 CE, and the concept was not fully developed until 1936 CE by C. S. Lewis in his Allegory of Love.

These authors were both writing at a time when the understanding of Egyptian hieroglyphics (in Paris’ case) and Mesopotamian cuneiform (for Lewis) was in relative infancy. Many works, from both ancient cultures, had yet to be translated – most famously, The Love Song for Shu-Sin (c. 2000 BCE) from Sumer, considered the world’s oldest love poem, which was not translated until 1951 CE by Samuel Noah Kramer. Works from both cultures that had been translated were not often widely publicized outside of anthropological circles.

Accordingly, writers like Paris and Lewis interpreted the literature of courtly love as something unprecedented in world literature when, actually, it was not; it was simply new to medieval Europe. The Egyptian and Mesopotamian cultures both regarded women highly, and their literature bears witness to that. Somehow, whether as religious allegory or role-playing or simply through the efforts of one woman, the poets of Southern France – with no knowledge of the passionate poems of Mesopotamia or Egypt – produced the same sort of literature in a culture which did not support that vision. Women were consistently devalued and denigrated throughout most of the Middle Ages but, in the poetry of courtly love, they reigned supreme.

Bibliography

- Barber, M. The Cathars: Dualist Heretics in Languedoc in the High Middle Ages. Routledge, 2000.

- Cantor, N. F. The Civilization of the Middle Ages. Harper Perennial, 1994.

- De Rougemont, D. Love in the Western World. Princeton University Press, 1983.

- Duby, G. Love and Marriage in the Middle Ages. University of Chicago Press, 1996.

- Gies, F. & J. Women in the Middle Ages. Harper Perennial, 2018.

- Hollister, C. W. Medieval Europe: A Short History. John Wiley and Sons, 1964.

- Kelly, A. Eleanor of Aquitaine and the Four Kings. Harvard University Press, 1991.

- Kramer,S. N. History Begins at Sumer. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1988.

- Lacy, N. J. The Arthurian Encyclopedia. Peter Bedrick Books, 1987.

- Lewis, C.S. The Allegory of Love. Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Lindahl, C. et. al. Medieval Folklore: A Guide to Myths, Legends, Tales, Beliefs, and Customs. Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Parry, J. J. Art of Courtly Love by Andreas Capellanus. W. W. Norton & Company, 2014.

- Power, E. Medieval Women. Cambridge University Press (1997-10-13), 2019.

- Staines, D. The Complete Romances of Chretien de Troyes. Indiana University Press – Indiana University Press, 1991.

About the Author

Joshua J. Mark (published 2019)

A freelance writer and former part-time Professor of Philosophy at Marist College, New York, Joshua J. Mark has lived in Greece and Germany and traveled through Egypt. He has taught history, writing, literature, and philosophy at the college level.

Creative Commons reprint.