By Greta Aurora

Studying Sex Differences

When studying sex differences in animals, biologists divide species into two categories: sexually monomorphic and sexually dimorphic. In monomorphic species, males and females can be difficult to tell apart. In dimorphic animals, on the other hand, the sexes differ considerably in terms of size, colour or other physical characteristics. It’s possible to infer a lot of information about the mating behaviour of a species by determining whether it’s sexually monomorphic or dimorphic.

Most animals fit clearly into one of these two categories – but humans do not. We possess both monomorphic and dimorphic features. But before I talk more about humans, let’s take a closer look at the characteristics of monomorphic and dimorphic species.

Sexual Monomorphism

When males and females are roughly the same size, it is safe to assume males don’t routinely fight each other to gain access to females. If males actively competed with each other physically, a larger size would be an advantage, so they would’ve evolved to be bigger than the females.

Monomorphic animals are generally monogamous and display long-term pair-bonding. If neither sex is much more colourful than the other, then sexual selection based on physical traits probably doesn’t play a huge role in their mating. Behavioural traits are a lot more important, and females prefer to mate with males who have proven they are willing to share parenting responsibilities.

Females expect to be courted by delaying mating, in order to assess potential mate’s dedication and paternal instincts. Female birds often act helpless to see how the male reacts.

Twin births are common in monomorphic animals, because the two parents can work together to look after more than one offspring at a time. Also, due to monogamous pair bonds, the majority of males get a chance to reproduce. But females do sometimes abandon their long-term mate and form a bond with another.

Some examples of sexually monomorphic species are wolves, gibbons, beavers, swans, penguins and bald eagles.

Sexual Dimorphism

In dimorphic species, two sexes vary physically quite significantly. In many mammals, males are bigger than the females. In some spiders, on the other hand, females are a lot larger than the males. In a lot of birds, males are much more colourful and sing to attract females.

In some species, males have not only evolved to be noticeably larger and stronger than females, but they may also have unique body parts meant to be used as weapons when they fight each other for dominance. These males are also a lot more aggressive than their female counterparts, due to their higher testosterone levels. That’s why these animals are often referred to as tournament species.

In dimorphic species, females are attracted to physical signs of male health and strength. The largest male in the group is often the most desirable partner, because he is able to provide physical protection. These dominant males usually have a number of sexual partners, but they abandon their mates and offspring. Therefore, females tend to be the only parent looking after their young, and therefore they rarely give birth to twins.

Because a minority of dominant males has access to a majority of females, physically weaker males don’t get to reproduce. Wherever polygamy is practiced, there’s going to be a lot of incels.

In these species, the life spans of males and females tend to differ significantly, too, with females living longer than males.

Where Do Humans Fit in the Picture?

Humans may seem monomorphic in some ways and dimorphic in other ways. Of course, in most cases, it’s easy to tell men and women apart. But we don’t look as different from one another as, for instance, male and female deer, lions or peacocks do.

Although the average man is larger than the average woman, the difference in size is not as significant as in many dimorphic species. The most noteworthy physical sex difference in humans is in upper body strength: the average man has 75% more arm muscle mass than the average woman. The overlap between male and female distributions of upper body strength is less than 10%. This has some crucial implications in everyday life, especially with regards to physically demanding professions.

Men also tend to have higher bone density, which makes them less vulnerable to injury. This difference may not matter much at an everyday setting, but it could be a matter of life and death in the battlefield.

Muscle mass and bone density are largely influenced by testosterone. This hormone also has a significant effect on behaviour, and men clearly have a lot more of it than women do. This fact alone could possibly tilt the scale towards dimorphism in humans, but it’s not quite that simple.

It is true that the average man is more aggressive than the average woman, and testosterone is to blame for this. However, some women are actually more aggressive than the average man, despite having nowhere near the same testosterone levels. It has been established that more testosterone doesn’t make a woman more aggressive. In fact, it’s not clear what causes aggression in women. There are a few theories, centred mostly on brain function. One of the most likely candidates is the amygdala, but no one knows for sure.

This example illustrates that biological differences don’t necessarily make a species dimorphic, because biology doesn’t always translate clearly into behaviour.

Let’s examine some personality traits to see if we can identify any obvious differences in behaviour! Looking at the Big Five personality traits is a good starting point. These are openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness and neuroticism.

Numerous psychologists have replicated the same results when studying gender differences in these five traits. No one has found any significant differences in conscientiousness. In openness, some differences arise only if we break this trait down into several constituent parts. For example, women tend to score higher on their appreciation for aesthetic experiences, while men are more drawn to intellectual experiences. But the sexes don’t differ in their overall levels of openness.

Women tend to score slightly higher on extraversion than men do, but again, this is not a very pronounced difference. Women also score higher on neuroticism, which is the amount of negative emotions experienced. This probably results from women spending all their time with their infants after giving birth. In order to protect a tiny, very vulnerable baby from harm, women have to be incredibly cautious and protective. That’s why women generally worry more than men do. To paraphrase Jordan Peterson, the feminine unit is not woman by herself, but woman and child. The female nervous system is that of a mother.

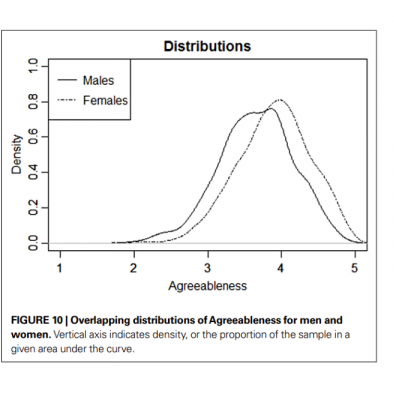

The most significant personality difference between the sexes is in agreeableness. But even here, there is a great overlap, and the differences only become evident at the extremes of the curve. What we see here is that the most agreeable people are likely to be women, and the most disagreeable people are likely to be men. Combined with high testosterone levels, this is the reason most violent criminals are male. But the majority of men and women don’t diverge very much in terms of agreeableness.

Those who are following my work will know that I’m fascinated by evolutionary psychology. But the more research we read from this field, the more we’re going to find ourselves focusing on the differences between the sexes, especially with regards to mating. Evolutionary psychologists tend to think in terms of extremes: they represent men as highly aggressive and competitive in their pursuit of professional and reproductive success, and desiring not much more than youth and beauty in a woman. And they represent women as desperate to secure a successful partner, despite knowing he won’t be faithful. In this hugely simplified world, men and women both want one thing, albeit a different one: men only want sex, and women only want a family.

Although evolutionary psychologists like David M. Buss, Geoffrey Miller and Robert Wright have made significant contributions to our understanding of human nature, they often fail to look at the larger picture. They tend to apply the male competition – female choice model to human mating, which is generally true for sexually dimorphic species. But human mating actually resembles that of monomorphic animals is various ways.

Human males have traditionally been involved in parenting, and they are therefore a lot more selective about their long-term mates than the males of dimorphic species. That’s why women make such a great effort to look desirable.

Also, women tend to choose their partner more on the basis of their personality, as well as their ability to provide resources and their inclination to commit long-term. Women still carry the heavier reproductive burden, but they are not necessarily choosier than men are – they just take different considerations into account.

Proponents of sexual dimorphism in humans will point out that women generally live longer than men, and polygamy has been common throughout our history. It is true that men have traditionally died younger, but that used to be mostly due to fighting in wars and working in dangerous environments, such as mines. The life expectancy gap has been consistently narrowing. For example, in the UK between 1991 and 2014, it shrunk from 3.8 to 2.4 years.

As far as polygamy is concerned, it’s true that it had been permitted through most of history, in many different cultures. There were times when it was necessary, exactly because so many men had died in war. But, for the most part, monogamous relationships are the norm, even in societies that allow polygamy.

It’s important to note that our species is highly adaptable to extreme conditions. For instance, if needed, we can survive on an exclusively carnivorous or herbivorous diet for a long time. Thanks to our creativity, we can survive in a desert, as well as in Antarctica. Therefore, we have every reason to believe that our mating strategies are not carved in stone, either.

We don’t have to commit ourselves to being just one thing. We must accept that we have some monomorphic and some dimorphic characteristics, and we can express these in various combinations, depending on the challenges we face.

As neuroscientist Robert Sapolsky said,

“We are not a classic pair-bonded species. We are not a polygamous, tournament species either… What we are, officially, is a tragically confused species.”

We are not necessarily confused, though… We have a lot of potential, and we are the masters and mistresses of adaptation.

“The life expectancy gap has been consistently narrowing. For example, in the UK between 1991 and 2014, it shrunk from 3.8 to 2.4 years.”

I have looked at the year-by-year male and female life expectancy statistics of many nations, records which go as far back as the 1700’s in some nations, and I observed a change in trends over centuries:

At first, in the 18th and 19th centuries, the life expectancy gender gap remained stable in every nation, with a steady female advantage of 1-3 years everywhere, with no exceptions on record.

Later, over the course of the 20th century (the Feminist Century during which most of history’s feminist laws were passed) the gap began to widen, with the female advantage gradually creeping up as high as 6-8-years in Western nations, or even as high as 8-14 years in the former Soviet Bloc.

Finally, toward the end of the 20th century, as “Men’s Movements” finally started reacting to all the feminist changes and advised men to focus less on women and more on their own male interests, the life expectancy gap started gradually closing in most nations.

In almost every nation, the gap is still larger than it was before the 20th century, but in most nations today the gap is slowly narrowing.

The female life expectancy advantage seems to have peaked in the 1970’s-1980’s in the West, and in the 1980’s-1990’s worldwide. The gap was widest in socialist and recently socialist nations, and has remained smallest in conservative Muslim and primitive traditionalist societies.