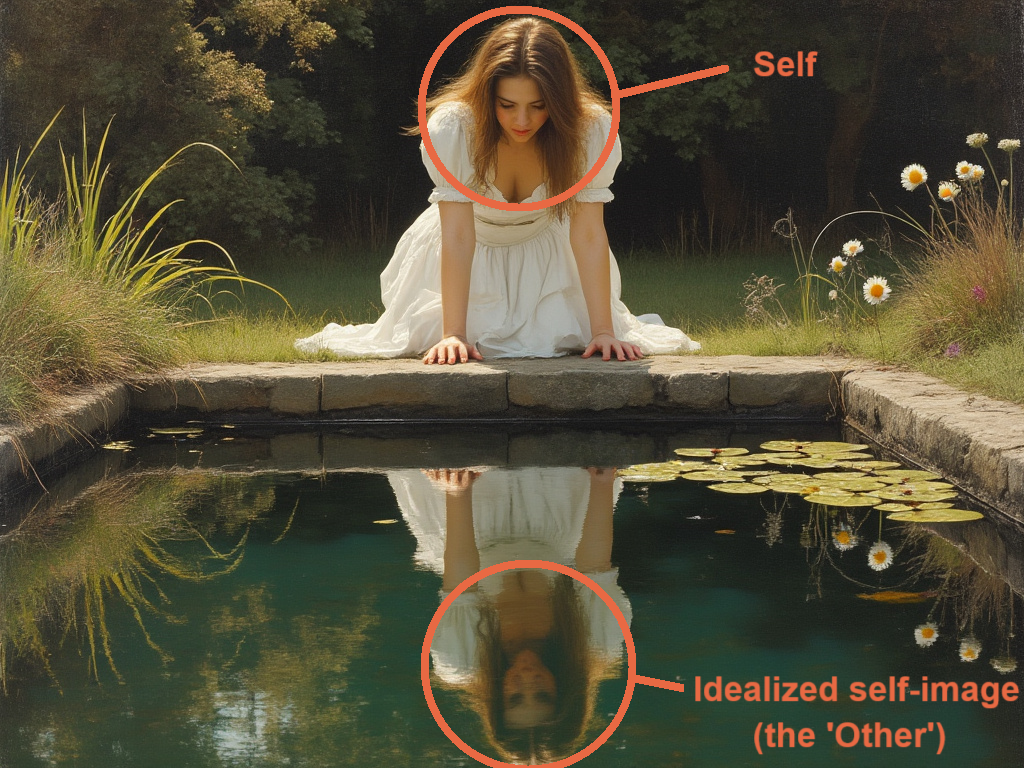

The question is sometimes asked of whether narcissistic women are morally responsible to something other than, or outside of themselves? The answer is yes; they are responsible to a particular kind of self-image — not an exact copy of themselves but an “idealized other” whom they strive to identify with, to emulate and to honor.

Such behavior acts as a substitute for moral responsibility expected by a traditional society, a family, husband or by holy laws enshrined in religious texts and culture. Not imitatio de Christi, but rather imitatio de narcissi — i.e., being morally responsible toward oneself alone.

It’s a strange perversion of what we used to consider our social duty.

This is why, when we read the classical story of Narcissus, he speaks to his own image as if it were not himself but some other whom he pledges to serve. As Narcissus discovered, being morally responsible toward self-image alone results in a maladaptive outcome for oneself, and for one’s relationships to the wider world.

The story of Narcissus’ self-idealization, as told by Ovid below, showcases how people strive to appease this idealised self. Note that Narcissus is responsible only to his image, to the exclusion of all other responsibilities:

“While he seeks to quench his thirst another thirst springs up, and while he drinks he is smitten by the sight of the beautiful form he sees. He loves an unsubstantial hope and thinks that has substance which is only shadow. He looks in speechless wonder at himself and hangs there motionless in the same expression, like a statue carved from Parian marble. Prone on the ground, he gazes at his eyes, twin stars, and his locks, worthy of Bacchus, worthy of Apollo; on his smooth cheeks, his ivory neck, the glorious beauty of his face, the blush mingled with snowy white: all things, in short, he admires for which he is himself admired. Unwittingly he desires himself; he praises, and is himself what he praises; and while he seeks, is sought; equally he kindles love and burns with love. How often did he offer vain kisses on the elusive pool. How often did he plunge his arms into the water seeking to clasp the neck he sees there, but did not clasp himself in them!

What he sees he knows not; but that which he sees he burns for, and the same delusion mocks and allures his eyes. O fondly foolish boy, why vainly seek to clasp a fleeting image? What you seek is nowhere; but turn yourself away, and the object of your love will be no more. That which you behold is but the shadow of a reflected form and has no substance of its own. With you it comes, with you it stays, and it will go with you — if you can go.

No thought of food or rest can draw him from the spot; but, stretched on the shaded grass, he gazes on that false image with eyes that cannot look their fill and through his own eyes he eventually perishes. Raising himself a little, and stretching his arms to the trees, he cries:

“Did anyone, O ye woods, ever love more cruelly than I? You know, for you have been the convenient haunts of many lovers. Do you in the ages past, for your life is one of centuries, remember anyone who has pined away like this.” I am charmed, and I see; but what I see and what charms me I cannot find — so great a delusion holds my love. And, to make me grieve the more, no mighty ocean separates us, no long road, no mountain ranges, no city walls with close-shut gates; by a thin barrier of water we are kept apart. He himself is eager to be embraced. For, often as I stretch my lips towards the lucent wave, so often with upturned face he strives to lift his lips to mine. You would think he could be touched — so small a thing it is that separates our loving hearts. Whoever you are, come forth hither! Why, O peerless youth, do you elude me? or whither do you go when I strive to reach you? Surely my form and age are not such that you should shun them, and me too the nymphs have loved.

Some ground for hope you offer with your friendly looks, and when I have stretched out my arms to you, you stretch yours too. When I have smiled, you smile back; and I have often seen tears, when I weep, on your cheeks. My becks you answer with your nod; and, as I suspect from the movement of your sweet lips, you answer my words as well, but words which do not reach my ears. — Oh, I am he! I have felt it, I know now my own image, I burn with love of my own self; I both kindle the flames and suffer them. What shall I do. Shall I be wooed or woo. Why woo at all? What I desire, I have; the very abundance of my riches beggars me. Oh, that I might be parted from my own body! and, strange prayer for a lover, I would that what I love were absent from me! And now grief is sapping my strength; but a brief space of life remains to me and I am cut off in my life’s prime. Death is nothing to me, for in death I shall leave my troubles; I would he that is loved might live longer; but as it is, we two shall die together in one breath.”

He spoke and, half distraught, turned again to the same image. His tears ruffled the water, and dimly the image came back from the troubled pool. As he saw it thus depart, he cried: “Oh, whither do you flee? Stay here, and desert not him who loves thee, cruel one! Still may it be mine to gaze on what I may not touch, and by that gaze feed my unhappy passion.” While he thus grieves, he plucks away his tunic at its upper fold and beats his bare breast with pallid hands. His breast when it is struck takes on a delicate glow; just as apples sometimes, though white in part, flush red in other part, or as grapes hanging in clusters take on a purple hue when not yet ripe. As soon as he sees this, when the water has become clear again, he can bear no more; but, as the yellow wax melts before a gentle heat, as hoar frost melts before the warm morning sun, so does he, wasted with love, pine away, and is slowly consumed by its hidden fire.1

[1] Ovid. (1916). Metamorphoses, with an English Translation by Frank Justus Miller. W. Heinemann.