The following are excerpts from Courtly Love as Religious Dissent – by Jeffrey B. Russell (1965).

Month: February 2024

Love in the Song of Songs

In the lead up to Valentine’s Day when Christian (and other) women look forward to receiving romantic love overtures from men. So I thought I would ask AI to clarify what is the nature of love as portrayed in the most famous lovers book in the Bible.

Question: “What is the Hebrew word used for the kind of love portrayed in the Song Of Solomon?”

ANSWER: The primary Hebrew word for love in the context of the Song of Solomon is ‘ahabah’. Although it does not explicitly refer to romantic love or sexual desire, within the context of this love song, it conveys deep affection, longing, and desire.

Even in the Septuagint, which includes a Greek translation of the Song of Songs, the word used is agape, though clearly the term eros is also applicable to the descriptions of longing and desire that take place between the two lovers.

Ahabah, agape and eros described in Songs are examples of reciprocal love, unlike the unidirectional, medieval practice of romantic love which requires sycophantic male love service toward pedestalised women. With these distinctions in mind, we can say that Christians who wish to celebrate romantic love, whether on Valentine’s or any other day, can be justifiably be charged with practicing heretical versions of love.

As a second note of clarification, St. Valentine had nothing to do with the concept of romantic love during his life, nor did romantic love play a part in the early legends that surrounded him. His namesake only later became associated with courtly & romantic love through a fanciful revisionism in the Middle Ages via poets like Chaucer who fabricated a link between the saint and romantic love. That conflation was continued by William Shakespeare, John Donne and many other poets, leading to the popular conception of romantic chivalry we inherit in today’s Valentine’s celebration.

‘La Querelle Des Femmes’: The Birth of The Feminist Movement

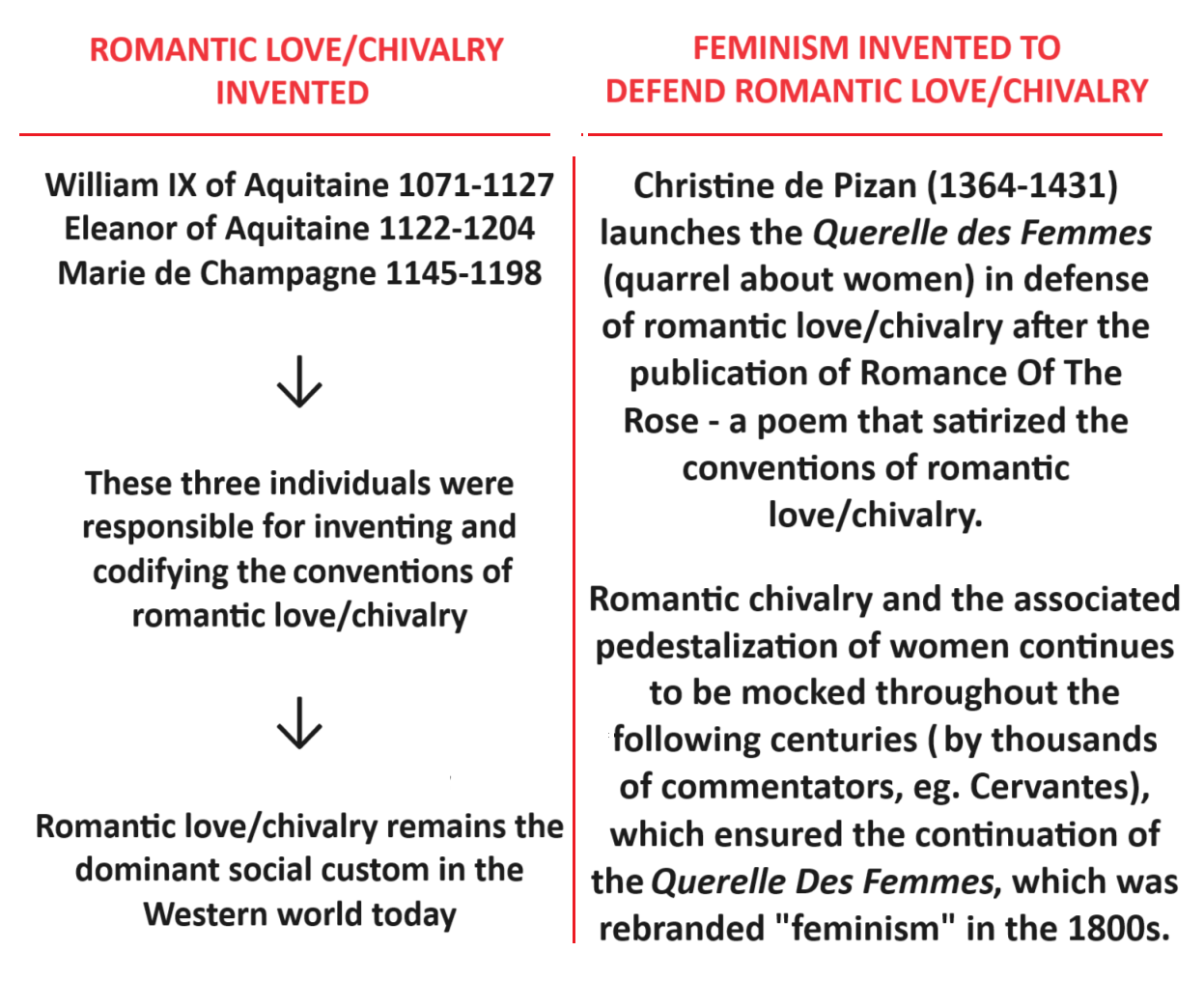

Not long after romantic chivalry was invented and popularised a millennium ago, some medieval authors began to make jokes about the outlandish male sycophancy and pedestalisation of women that the new tradition entailed. Christine de Pizan (1364-1431), a woman whom French feminists characterise as the “first feminist,” took public offense the attack on romantic chivalry and on female purity, which she considered a degradation of women’s dignity which feminists today would label misogyny.

Christine’s response launched a movement called La querelle des femmes (the quarrel about women’s rights), which continues today under the name ‘feminism.’ The basic theme of the centuries-long quarrel revolved, and continues to revolve, around advocacy for the rights, power and status of women, and thus the querelle des femmes serves as the originating title for the modern feminist movement.

Feminist historian Joan Kelly characterizes this early history of feminism as follows:

We generally think of feminism, and certainly of feminist theory, as taking rise in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Most histories of the Anglo-American women’s movement acknowledge feminist “forerunners” in individual figures such as Anne Hutchinson, and in women inspired by the English and French revolutions, but only with the women’s rights conference at Seneca Falls in 1848 do they recognize the beginnings of a continuously developing body of feminist thought.

Histories of French feminism claim a longer past. They tend to identify Christine de Pisan (1364-1430?) as the first to hold modern feminist views and then to survey other early figures who followed her in expressing pro-woman ideas up until the time of the French Revolution…

The early feminists did not use the term “feminist,” of course. If they had applied any name to themselves, it would have been something like defenders or advocates of women, but it is fair to call this long line of prowomen writers that runs from Christine de Pisan to Mary Wollstonecraft by the name we use for their nineteenth- and twentieth-century descendants. Latter-day feminism, for all its additional richness, still incorporates the basic positions the feminists of the querelle were the first to take.1

When we consider the longevity of this movement, along with its aim to increase the power of women through the exploitation of gynocentric chivalry,2 we might be forgiven for believing its time for romantic chivalry and the associated gender wars it has sparked to be finally put to rest.

A short summary:

References:

[1] Kelly, J. (1982). Early feminist theory and the” querelle des femmes”, 1400-1789. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 8(1), 4-28. See also: Bock, G., & Zimmermann, M. (2002). The European Querelle des femmes. Donavín G., Poster, C. Utz, R.(coords) Medieval Forms of Argument Disputation and Debate, Or: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 127-156.