To understand Jordan Peterson’s encouraging of young men to become heroes in service to the maternal principle, especially within the context of marriage, we must turn to his ideological pedigree in the formulations of Carl Jung. Jung characterized the hero archetype as bound up with what he called ‘the Great Mother archetype,’ believing that male heroism rests on resisting the negative mother or, alternatively, acting as servant to a positive mother. Jung’s mother-tied concept of the hero is laid out in his Symbols of Transformation, an idea that Peterson reiterates when he treats motherly women as an axis mundi who provide essential meaning to male striving (a position I touched on in a 2017 article titled The Gynocentrism of Jordan Peterson).

Peterson refers to Freud’s claim that the Oedipus myth is a “failed hero story,” but he proposes, following Jung, that relationships men have with mothers and other feminine figures might be more positive and more inspirational than the taboo interpretation insisted upon by Freud. Whether such relationships with inspiring or nurturing female figures be positive or negative, Peterson appears to miss Freud’s point that both of these options still belie an incestuous entanglement with mother imagos.

In this video for example, Peterson claims that positive mothers give birth to heroes. He illustrates this point by reference to an image of Hercules who floats on a chaotic ocean in what he refers to as a “feminine boat,” which is a metaphor for an uplifting, positive mother. In this lecture he reminds his female students of their role in creating and sustaining heroes: “That’s what you’re trying to produce if you’re a good mother, it’s this figure that can go out into the unknown armed, accurate and able to pay attention,” and he adds that mothers create male heroes who “can take on the troubles of the world.”

Might this be why Peterson places such strong emphasis on women becoming mothers – that they might breed and nurture the next generation of male heroes? That male heroes might then have a female boat to float their heroic mindset? Further, what might happen if we replaced all of Peterson’s inspiring female figures with inspiring male figures?

There is no way, at least in my reading, of understanding Peterson’s kind of feminine-tied heroism as anything other than a mother fixation. The archetypalist James Hillman agrees that “contrary to the classical analytical view, we would suggest that the son who succumbs and the hero who overcomes both take their definition through the relationship with the magna mater… When mother determines the role, then regardless how it is played its essence is always the same: a son. And, as Jung says of assertive heroism:

“Unfortunately, however, this heroic deed has no lasting effects. Again and again the hero must renew the struggle, and always under the symbol of deliverance from the mother”1

What we are dealing with by over-emphasizing the role of mothers is the creation of two male archetypes: Mother’s son (Oedipus), and Mother’s hero (Hercules). Readers will be aware that Hercules’ relationship with female figures leaves him riddled with guilt and pathology, and Oedipus is the ultimate example of malignant, incestuous heroics who is unable to enact his heroism as anything but the result of his relationship with female figures. But the Oedipal path is not the only way to view the male hero, as Hillman describes;

The maternal dragon demands battle and the hero myth tells us how to proceed. But suppose we were to step out altogether from the great mother, from Jocasta and Oedipus and the exhausting, blinding heroics…. If Freud was right that Oedipus is the stuff of neurosis, then the corollary follows that Oedipus-heroics are the dynamism of neurosis. Heroism is thus a kind of neurosis, and the heroic ego is neurotic ego. Creative spirit and fertile matter are there embraced and embattled to the destruction of both.2

So far I’ve been referring only to a classical Jungian concept of the male hero, and to Jordan Peterson’s reliance on same.3 The hero archetype in Jung’s writings is intimately bound up with the mother archetype (being a hero for mother / or fighting against the dragon mother), or otherwise tied up with feminine figures (inspiratress, or muse). These are archetypes that can be contrasted with other kinds of male hero who have zero entanglement with feminine figures.

Aside from the mother’s heroes described above, there are a number of variations detailed by Joseph Campbell in his famous work The Hero With a Thousand Faces. Campbell wasn’t a Jungian, and he was suspicious of Jungian dogmas, once claiming “I’m not a Jungian! I’m much more interested in diffusion and relationships historically than Jung was, so that the Jungians think of me as a kind of questionable person.”4 Likewise, Campbell’s conception of the hero is not beholden to Jungian or Freudian orthodoxies.

Campbell paints the hero’s journey as a stepping off into the unknown, into a more gutsy hero’s journey as compared with stepping out into the world as ‘mother’s hero’ to do her bidding. As Campbell characterized it, a more masculine hero’s journey might entail leaving the mother-world behind and seeking atonement with the father, which Campbell describes; “When the child outgrows the popular idyl of the mother breast and turns to face the world of specialized adult action, it passes, spiritually, into the sphere of the father—who becomes, for his son, the sign of the future task… Whether he knows it or not, and no matter what his position in society, the father is the initiating priest through whom the young being passes on into the larger world.”

As one facebook poster put it;

“The hero’s journey as described by Joseph Campbell begins by ‘Separation,’ the departure from the status quo. To me this personally I associate this to stepping out of and leaving the gynocentric view of the status quo.”

Leaving behind the gynocentric world is precisely what is entailed. To whit, Campbell writes:

This first stage of the mythological journey—which we have designated the “call to adventure”—signifies that destiny has summoned the hero and transferred his spiritual center of gravity from within the pale of his society to a zone unknown. This fateful region of both treasure and danger may be variously represented: as a distant land, a forest, a kingdom underground, beneath the waves, or above the sky, a secret island, lofty mountaintop, or profound dream state; but it is always a place of strangely fluid and polymorphous beings, unimaginable torments, superhuman deeds, and impossible delight. The hero can go forth of his own volition to accomplish the adventure, as did Theseus when he arrived in his father’s city, Athens, and heard the horrible history of the Minotaur; or he may be carried or sent abroad by some benign or malignant agent, as was Odysseus, driven about the Mediterranean by the winds of the angered god, Poseidon.5

That refers to the father-inspired hero. For the mother-bound hero, however, this broader journey is renounced in favor of remaining within the family complex and enacting a pale heroism on its behalf. As Campbell tells;

Often in actual life, and not infrequently in the myths and popular tales, we encounter the dull case of the call unanswered… The literature of psychoanalysis abounds in examples of such desperate fixations. What they represent is an impotence to put off the infantile ego, with its sphere of emotional relationships and ideals. One is bound in by the walls of childhood; the father and mother stand as threshold guardians, and the timorous soul, fearful of some punishment, fails to make the passage through the door and come to birth in the world without.5

Campbell entertained a few gynocentric beliefs of his own that were popular in academia in his time. Mercifully, he formulated the hero’s Journey on the principle of men stepping out into new horizons without the need for maternal or feminine fixations, and on that journey he said it is frequently male figures who serve to encourage, inspire and guide the male hero – fathers, brothers, ancestral spirits, male mentors and guides. Campbell’s hero provides a welcome change from Oedipal hero which sees men going from enmeshment with mothers straight into the married arms of a maternal wife as Peterson encourages for young men. In other words Campbell’s hero template for men is explicitly Red Pill, as contrasted with gynocentric fixation on parental figures and roles.

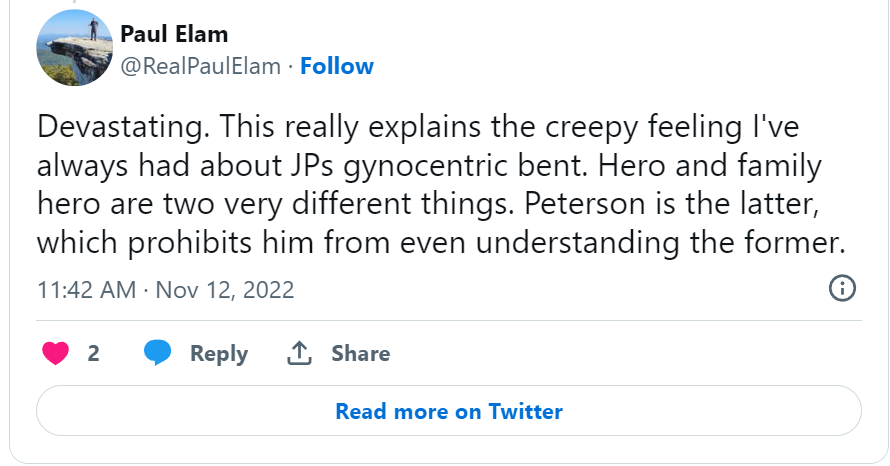

Paul Elam, who has devoted much of his life to imparting the wisdom of self-determinism to men, made this incisive response regarding the comparison of Campbell’s and Peterson’s concepts of the hero:

After floating a description of this ‘Campbellian’ kind of hero on Twitter and describing his more masculine pedigree, a few people asked whether this path was suitable for all men; eg., straight, gay, soft, hard, nerd or Canadian lumberjack. The answer is yes, because we all have maternal influences dominating our childhood and have a choice to move into adult life remaining enmeshed or obsessed with feminine forces (Peterson), or otherwise to place the accent on atonement with the world of men and with adventure (Campbell). The choice, as always, is yours.

References:

[1] James Hillman, ‘The Great Mother, Her Son, Her Hero, And The Puer,’ in Fathers and mothers; five papers on the archetypal background of family psychology, Spring Publications (1973)

[2] Karl Kerenyi, James Hillman, Oedipus Variations: Studies in Literature and Psychoanalysis. Spring Publications (1995)

[3] Note: As well as deriving inspiration from Jung’s conception of the hero, Peterson leans heavily on the work of Jungian Erich Neumann (The Great Mother, and The Origins And History of Consciousness) whose writings display an obsession with mother imagery. For readers wanting to investigate how irrational Neumann’s ideas are, see the excellent critique by Wolfgang Giegerich titled ONTOGENY = PHYLOGENY? A Fundamental Critique of Erich Neumann’s Analytical Psychology (1975).

[4] Joseph Campbell. An open life: Joseph Campbell in conversation with Michael Toms. Larson Publications (1988)

[5] Joseph Campbell, The hero with a thousand faces (rev. ed.). Bollingen Series, 17. (1990)