Despite attempts to dismiss courtly love as something that has never existed outside of male fantasy and medieval literature, the following excepts from a formal academic study show that tenets of courtly love were, and remain today, supported by real persons of both sexes. – PW

Abstract:

Summary.-This pilot study measured current acceptance of medieval rules of love operationalized in two scales adapted from an important 12th-century Latin treatise about courtly love. One item about a doctrine in the treatise was added to measure “perfect” love. Subjects were Hispanic and Caucasian students at a south-western Catholic university (45% men, 55% women). Scores on the scales of 11 Male Courtesy Norms did not significantly correlate with those for Rubin’s romantic love scale, but scores for 31 Action Norms did. There was general acceptance that women expect men to follow medieval rules of love concerning Male Courtesy. Some significant sex and ethnic differences were found, especially in regard to Action Norms. Results were interpreted to modify current understanding of courtly love by identifying men’s courtesy as a prerequisite for love. Demographic variables were interpreted as evidence of cultural scripts that program romantic experience to give women social and personal control of men.

Questions: Norms for Male Courtesy and Male-Female Action (Answered with agree/disagree) 1. As you would flee the plague, avoid being a scrooge (a mean-spirited man who amasses wealth); instead, embrace generosity. |

Today’s expectations

The current study shows that men and women agreed that women accept the norms for Male Courtesy… As Lafitte-Houssat (1966) and Kelly (1968) wrote, courtly love taught social and personal propriety to medieval men in erotic relationships. The current acceptance of a number of the norms for Male Courtesy indicates that today’s expectations of a potential male lover resemble these norms found in Marie of Champagne’s 1185 CE program as reported by Andreas Capellanus.

Courtly Love as a Vehicle For Feminine Control

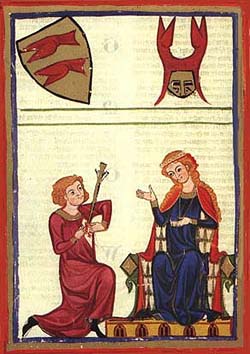

By developing ways to handle the excess of men to women (Moller, 1958-59; Guttentag & Secord, 1983), medieval courtly love provided alternative behaviors besides violence to resolve conflict (Brody, 1969; Koenigsberg, 1967). By including norms that also can be related to courtesy, courtly love taught men a way to express tenderness rather than just erotic passion (Kelly, 1968), and legitimated a level of control for women in heterosexual relationships analogous to their increased domestic power in the 12th century (Lafitte-Houssat, 1966).

Although recognizing this new power, Lafitte-Houssat (1966) claimed 12th-century men only fictionalized women “as a feudal sovereign” (p. 22). Similarly, Duby (1983) considered courtly love an escapist male fantasy. Boone (1987) argued that the image of courtly love “maintained a hierarchy of male dominance” (p. 42). However, medieval courtly love also provided women a structure to contest for personal control. This empowerment gave society a way to structure the darker side of passionate love identified by Peele (1988) as addictive love. Without knowing how or in what context the norms developed, most men and women today agree with the courteous love proposed by Andreas Capellanus in 1185 CE.

Nevertheless, as the low acceptance of Item 7 by only 31% of men and 30% of women about obedience to women shows, the overt control of men which was a part of courtly love is generally not identified as part of the modern scenario. According to Koenigsberg (1967), Item 7 (male obedience to women) showed psychological growth in Western culture. Koenigsberg also pointed out that, despite the potential of psychological growth that could come from obedience to women, such courtly obedience was also a parody of submission, for the man’s “deference involves the maintenance of emotional distance” (p. 38). Rejection by modern youth of this obedience may be a refusal to accept either this emotional distancing or the passive role required in such distance.

The instrument needs refinement. For instance, the diction should be simplified and the negatives removed. Furthermore, Andrew’s original second commandment should be restored (as in “Respect for my lover should keep me from sleeping around”). Nevertheless, responses to the 43 items have raised intriguing questions.

Research is necessary to determine the possibility that women determine men’s cultivated behavior by establishing an image of themselves as sovereigns to control male fantasies, rather than being enthroned by male patriarchy. Incorporating the operative Courtesy Norms into current love scales could expand our view of the scripts which direct erotic fantasies and judgements about relationships. Finally, responses of other ethnic and Hispanic groups to selected items, especially about courtesy and obsessiveness, could be analyzed.

References:

–BHODY, J. (1969) La princesse de Cleves and the myth of courtly love. University of Toronto Quarterly, 38, 105-135.

–BOONE, J. A. (1987) Tradition counter tradition: love and the form of fiction. Chicago, IL:

Univer. of Chicago Press.

–GUTENTAG, M., & SECORD, P. F. (1983) Too many women? The sex ratio question. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

–KELLY, D. (1968) Courtly love in perspective: the hierarchy of love in Andreas Capellanus. Traditio, 24, 119-147

–KOENIGSBERGR,. A. (1967) Culture and unconscious fantasy observations on courtly love.

Psychoanolytic Review, 54, 36-50.

–LAFITTE-HOUSSAT, J. (1966) Troubadours et cours d’amours. [Troubadours and courts of love.] (3rd ed.) Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

–MOLLER, H. (1958-59) The social causation of the courtly love complex. Comparative Studies in Socieo and History, 1, 137-163.

_________________________________________

STUDY SOURCE : CONTRIBUTIONS TO PSYCHOHISTORY: XIII. COURTLY LOVE TODAY: ROMANCE AND SOCIALIZATION IN INTERPERSONAL SCRIPTS