[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ufdpf7bCXBo&w=550&h=370]

In several posts and on various other blogger’s comment threads I’ve debated that the social paradigms of chivalry and feminism are cultural engineerings of the feminine imperative. I delved into the history of chivalry in The Feminine Imperative – Circa 1300 and made my best attempt to outline the history of chivalry, the feminine bastardization of it and how it was the cultural parallel and precursor to feminism. Naturally the more romantic leaning of my critics chose to keep their noses in their holy books and epic poems rather than take the time to consider the historical underpinnings of what we now consider chivalry and monogamous romantic love.

________________________________________________

A search phrase I was recently using came back with this imbedded in the result:

“Cultural historians believe that romantic love was created sometime in the 14th century”.

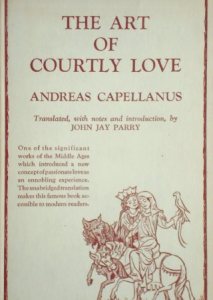

The link stated that the idea of “Romantic Love” was created by troubadours in verses by the idea of “Courtly Love” that arose in its beginnings the the end of the 12th century. So I started going back,back,back,back, back (-Chris Berman) and I found this: The Art of Courtly Love

The book is important. The foreword by John Jay Perry was written in 1941. The title of this book is “The Art of Courtly Love” but it is actually a Victorian Era title imposed on the work that has several other different titles as a function of the era when the translation was performed, country where the translator lived, and particular social attitudes prevalent when and where the translator produced the translation. I think the “Romantic Era” was when these ideas of “courtly love” finally percolated up into mainstream thought, well, actually women’s mainstream thought, and defined love as we believe it be today, or at least defined it as women wish that definition to be imposed on men.

The title I generally use is “Treatise on Love”. Andreas Capellenus was the Chaplain of Countess Marie, and the preface goes into all of this history and I don’t want to get it into it. Read it.

It is the seminal work on the subject and there is no earlier work by a European. There is reference to Ibn Hazm, an Islamic writer from Spain, who began to define the idea of “love” in Islamic cultures. It went through a series of other writers in the 13th century and orally communicated through verse and song during the 14th century and made its way into the consciousness of western thought from the 14th century on.

The key thing is that these Troubadours were not some “traveling band” singing for their supper. Maybe later, but at this time, they were major nobles, from both the nobility and the higher noble classes. The first major one referenced was Duke William of Aquitaine, who was Marie’s grandfather. These were important people of the time. This would maybe be like, God forbid, Senator Harry Reid, breaking into a song after dinner about the importance of passing spending bills to ease the particular issues about the “sequester” that are key issues to Democrats or Ben Bernake letting loose about the Quantitative Easing. Ok, maybe not exactly.

The issue at the time, was that, as the historians state, that “Love as we know it did not exist. Marriage was as much as about land and politics as anything else”. It was said you “Married a fiefdom and a wife got thrown in the bargain”. Imagine a time where firelight and sunlight were practically the only light, when people rarely traveled more than 12 miles from their place of birth, when nothing, and I mean nothing, changed. The major cathedral built in Nimes took 38 generations to complete. The skyline never changed, towns remained the same. There were no books. None. All knowledge was conveyed orally and generally died with a person. The only cultural conditioning was what you got by watching the people you saw. And you saw very few people. Even at the peasant level, most marriages were the tossing together of two available young people, and that was that. But particularly at the noble level, all marriages were entirely based on practical considerations and nothing to do with “love” as we know it.

And the major church writers the time, just skewered women. The preface named several, and while I can’t find actual text of the writers specific to women, Bernard de Morlaix, John of Salisbury, I can find overall references to what they said about morality in general. They were a group that very much about self control. And it was thought that due to the “wickedness” of women, it was probably superior to remain a virgin. And thus the idea of the “celibate” priest was born. He could not be “godly”, and should be suspect, if he allowed himself to come under the temptation of women.These guys were definitely the “Red Pill” writers of the time. The general idea was not so much that sex was bad, but women were so bad, and sex was lure, the hook, so they damned sex as a means to keep men from getting ensnared in the traps and wickedness that women lay for men. And the thought has a little bit of merit, I must say.

So, think about this. The men in power at the time, saw some of the stuff we see, and they gave a huge “thumbs down” on women. Huge.

Now, heading into the second 500 years of Christianity, throw a “rubbing elbows” with Moslems in Spain, and this idea of “love” starts to percolate about, sort of this “counter-culture” idea of the time. It did not exist at all before in European culture, this idea of “soul mates” and “intertwined” spirits and “the ennobling qualities of love”, love as the be all and end all, the very reason to live.

And it was made up.

By women. Duh?

So there were moments, during this period 1170-1250 were in certain places the women got control. It the case of this Marie, she got control of this region “Troyes” in southern France when her son was named to be noble over the region and he was 11 years old. So she accompanied him down there and was the defacto “regent” during his “minority”. Her husband became King while she was down there. So this was a woman of major influence. And her sister was married to someone that also became King of someplace else. Their mother had been both Queen of France and then Queen of England after she divorced the King of France. This was a powerful woman who got what she wanted. And two of the chief architects of “love” were her two daughters, who married extremely high status men.

The same thing happened at the same time in about 3 other major places in the area, and these women, began to “flirt: with idea of “Courtly Love”. Flirt maybe is a little weak of word. But the general idea of most writers about the theme is that they “Proposed it as countervailing religion or thought to Christianity.” Christianity had so vilified women during the past 200 years, and this “love” stuff was really one of the first “feminisms”.

And near I am can tell, it was literally the birth of the Feminine Imperative. At least, the birth of the version that we know today.

The general idea was this.

“Women are the love. Women give praise to men and the power of that praise is the driving motivator of men. All good things that men do are only done in the true spirit of love to earn the right to the love that the woman confers to the men. Women define what is good. Women confer status on men by allowing them to receive the love they receive from women as a result of high character and accomplishment”.

Sound familiar.

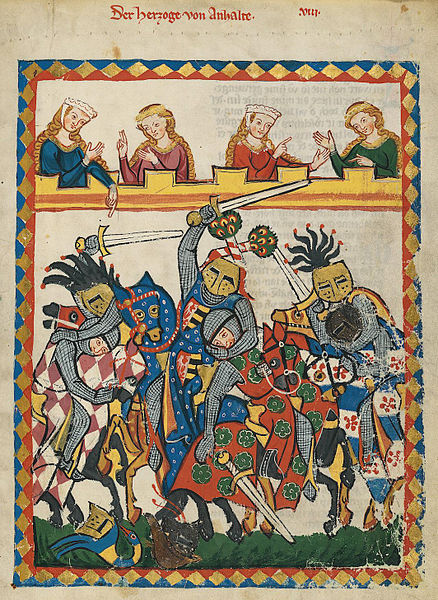

So that was why some “Sir Goodguy” white knight would tie the scarf of the woman around his neck during some contest. It was his sign to her that he was doing this brave dead for her love and his recognition that she saw him as good and worthy.

They actually created these things called “The Court of Love”. And these men and women, and you can imagine the men in those courts were the 12th or 13th century equivalents of Manginas, would literally “rule” on love. They would debate questions, actions, and then determine is an act was good or bad and then that further defined “love”. Remember again, this was not idle chit chat after dinner. These were the major movers and shakers of the time. This was the court that would go on to exert cultural and intellectual control over Europe until 1914. And really even later than that. For nearly 1000 years, the French held sway in everything and Paris was the center of the world. Except at this time, this part of France, the south was the big deal.

One example I saw was letter written by a man that said, he and a woman were having heated discussion of two points, (1) Can true love exists in a marriage. (2) Can there be jealousy between the married partners. The Countess, the Queen of Love, at that time wrote back and said “No, love cannot exist in a marriage. Love is freely given and asks for nothing in return. Marriage is a contract of duties. So there is no love in a marriage. And Jealousy is a prerequisite of love and since only lovers could be jealous and since married people were not lovers, then their could be no jealousy in a marriage. ” And that was that. The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Love had issued a ruling. And its weight was everything.

And needless to say, it was a mighty convenient development for women that were traded off into marriage as pawns attached to land. So it conferred the key power of social definition and the final say of what is good in men, and good in society, and that women should and will be the definers, and the arbiters, and the judges of all of that.

The translators, and this particular author John Jay Parry, mention that was nothing particularly distinguishing about Andreas Capellanus that would make it seem like he was the person to end up as this great literary figure that wrote a work that is “One of those capital works that explain the thought of a great epoch, which explain the secret of a civilization”. Parry said often, some of the prose was different in style and “meter”, such that it seemed “dictated” to him.

And frankly I am sure the whole book was “dictated” to him. That he was, in fact, as chaplain, the mouthpiece of these women, and his position as Chaplain allowed the viewpoints expressed to be accepted in a way that a work created and made public by women, given what it expresses, would have viewed more critically by readers. Keep in mind that it was written in Latin, and only those who were either Clerics or the nobility could read the thing. What wasn’t literally dictated, was more or less, transcribed thought, and he knew that Marie was final “editor” in the content. And his position, both as Chaplain, and his very livelihood, depending on her being happy with the finished product.

So let me make an analogy, and step just a little bit in time. Things are little muddled today cultural to make a similar one from a very current example.

Consider Hugh Hefner. And consider his show called Playboy After Dark. This was a time of much “friction”, the early 60s. Civil rights and racism are extreme issues. Sexual “freedom” is coming about. The “rights” of just about everyone are much talked about. The setting which was sort of this contrived “salon” from Paris. The set looked like a large living room in a swanky spiffy Playboy bachelor pad. All these “cool”, meaning avante guarde, “open minded”, intellectually superior, artistically superior, liberal people are just hanging out, having a spiffy party. Hef does more for civil rights in a minute than 50 writers do in 10 years by having Sammy Davis Jr on the show. Hef did more for women’s liberation by having a “guest” on the show to talk about it and the camera sees Hef nodding approval, than 50 screeching female professors could ever do.

So then that “cool” boy, that wants to be like Hef, all through the 60s and the 70s, the “cool boy” believes in Equal Rights, Racism, Feminism and this idea of “gender” and “race” being a culturally imposed concept. And that “cool” boy does it exactly because it is “artistically and culturally superior” than the conservative ideas of the time. So then imagine how pervasive both of those viewpoints on Racism and Sexism are today and how “religious” both have become in such a short time, historically. All of us have experienced the reaction of people to our Red Pill beliefs that border on religious arguments. And some of the biggest fighters of what we propose are men. So a philosophy can quickly move from the fringe and become core if the “right” people get behind it and push it.

So then imagine the same thing back in 1200, the “cool” boy, the son of the nobles, that reads latin, has a little bit of education, he thinks the Catholic church is a bunch of sticks in the mud. He is literally built, wired, for sex, to want women. And this idea of “love” makes absolute sense to him, or at least he wants it to make sense, because the top of line, highest status women, those noble women in that area between Barcelona and maybe, Bologna, were all giving approval to those men that bought into it. So by saying “I believe in Love” or “I am in Love’s army”, or “I am a soldier of love”, what he is saying is “I’m cool, man. Please like me.”

And just like today, any guy that goes against Feminism or attacks the behavior of women is shunned. I hurl some attack on women in comments to an article, and some woman comes back with “Oh, I be you just get you tons”. So in 1200, It is “No ‘Love”, then no ‘love’”, you were ostracized by women, at least the cool French Chicks who were the celebs of the day.

And so it takes hold, and as Feminism has co-opted the church, today’s women have imposed their viewpoint on church acceptance of divorce, premarital sex, with the whole idea of the “magic vagina” of women compelling those men into better behavior and better performance, and the woman has the right and the duty to punish him for failure to live up to the love that the woman has given him as a gift that he must continue to earn, the same thing happens with “love”. It co-opts the Catholic church of the day, and throughout the 13th and 14th centuries, “love” creeps into the morality and consciousness of the people at the time. The “love” thing is dominating the “court” and is leaks into the church in the relationship of accomplices that they first and second estate have which each other. It catches on and becomes the dominant aspect of the culture and women are “rehabilited”, seize control, and never let go. They have the “authority” because they have the “morality”, and they drive the course of society by controlling what is “moral” and what is “honorable”. And what constitutes both, from that point forward, are generally what is in the best interest of women, given their situation, given the time.

So why is this important to us?

First, the whole idea of “Courtly Love” was entirely hypergamistic. Entirely. The Capellanus book has as the heart of the second part, 9 dialogues. These dialogues define the Feminine Imperative.

Keep in mind, at this time, there might have been maybe 500 books floating around in total. And this is the only one on this topic available for a 100 years. The only other referenced work before this was Ovid “The Art of Love” and most scholars really see Ovid as more of a satire on the “treatises” written during his day, and not as a REFERENCE MANUAL that people today, including myself (pre-Red Pill) , see it.

I took it as “how to” book. And what it should be titled is “How to be a AFC Beta”. Also keep in mind that books were so rare, that everything thing was relayed as an oral tradition. Even as late at 1513, Luther said he had been a priest for 3 years before he ever even saw a Bible. And that’s the effing bible.

So here you are somewhere in 1200, and this major Noble dude guy, or high status babe, gets up and starts talking or singing about this new “love” thing, and everyone is nodding and agreeing. And if they don’t nod and agree, then they don’t get to be in the group, they’re fired. The High Status women turn on them, and they are ostracized.

So in the 9 dialogues, there are a series of conversations that men of one of three statuses would have with a women of one of the same three statuses. Those statuses being “commoner, noble, high noble”. And these dialogues set the ground work, the rules, of what both men and women of all three classes should, do, feel, and think about “love”. And “love” is only between those classes. Peasants don’t love. They need to stay on the farm and work it. They have no time for “love”. And love is only between people that aren’t married.

And there you go right there, with anachronistic thought. You probably thought, single people. No. Single people weren’t dating and marrying. No way. That was decided by someone else. You were probably going to be part of some arranged marriage. “Love” was between married people, at least married women and a man, but not married to each other. You can already see the way hypergamy is influencing the idea of “love”. Girl gets pawned off as a 14 year old or 15 year old as part of some arrangement between older family members. She probably didn’t like her husband very much, given what we know about women today. And he probably didn’t like her much either. I am sure there were just as many men when they first saw there “betrothed” thought, “Oh fuck, you have got to be shitting me. I have to marry this bitch?”

And in these dialogues, pure hypergamy is enforced and codified. The dialogues enforced class, at least enforced it for men. Men could try and love “up”, but most likely they couldn’t unless they displayed such extreme good character that their character was better than all of the available men in the class of the woman he was “hitting on”. But it also set a nice set of rules for women “move up”. But the women were the ones, in every case, to judge the men, the determine that even though the women were “moving” up, they still were to ones to say “OK, I’ll take you You are worthy of my love”.

And then it also codified acceptance for women to be able to “cheat” on their husbands. “Courtly Love” was only between people that were not married. They got around the 10 commandments, by stipulating that the true lover never asks for sex in return for his love. He loves merely for the purity of his love. And that the whole endeavor was supposed to remain entirely secret. That if it became public, then the “love” was dead. Over. At best he got a kiss, maybe an embrace. Gentlemen in the army of “love” never tell. And Gentlemen never demand sex. Which of course, all of this was bullshit. But since “Courtly Love” was “love” for “love”‘s sake then those husbands couldn’t get jealous, and nobody loves their husband anyway. So it gave a socially acceptable way for this woman that had this beta forced on her by marriage, then get out their and have exposure to the alphas that she truly wanted. And it gave her a social means to circumvent the church. And since everyone, at least everyone who mattered, was married to someone they didn’t like, then it was an early version of “Don’t ask; don’t tell”.

This also forms the basis of monogamy, as we know it, codified by women, in that the definition of it truly benefits women. “The true lover that truly loves only loves the one. He cannot love two. The sight of other women do not affect him because he has true love for his true love.” Notice that there are a lot of “he” and ‘his” words used. The book asserts that those men that would want sex with lots of women and have passion for someone other than “the one” under the guise of love is an an “ass”, mule, dressed up in the finest livery, but still an “ass”.

Schopenhauer said “Love! If you would have thought it up, your fellows would have thought you daft. The mere idea that because a woman allows you her favors, that you should support her for life.”

Well, it was thought up, by these women in the south of France, and it curled around and snaked its way into the current consciousness of people like it was something that people have done since the dawn of men. And it wasn’t.

When you read Capellanus’ statement of what “love” is, it is the seminal definition, the very “jump street”, the Genesis of the codification of “OneItis”. And when you read the dialogues, and then this list of the “Rules of Love” which is the part of the book that is most public, you see the fingerprint of the Feminine Imperative.

http://web.cn.edu/kwheeler/rules_of_love.html

I think at some point in my reading, someone had described Capellanus as being very “Copernican”,as in Copernicus, and astrology, threatening the religion and the concept of the world.

I say we use him again in a Copernican manner, as the very argument that the Feminine Imperative is an entirely contrived ideal.

And we reject “love”, as in the definition of it by Capellanus. We see it as the social manipulation that it was to orchestrate the emotions of men, and actions from those emotions, entirely for the benefit of women.

Churchill said “In England, it is permitted unless it is not permitted. In Germany, it is permitted only if it is permitted. In Russia, it is not permitted even if it is permitted. And in France, it is permitted, even when it is not permitted.”

To some degree that combination of all four “permitteds” describes the Feminine Imperative. It is permitted when they want it to be permitted and not permitted when they do not. Even if it is not permitted then it is permitted, if it is in the benefit of women. And especially, it is not permitted even when it is permitted, in the case where it might benefit men at the expense of women.

They only way to put a brunt on the Feminine Imperative is make them pay a cost for their behavior. And the best way for men to do that is the rejection of “love”.

In the words of YaReally, “The manosphere is the new counter-culture”.

We are the new “cool boys”. We are the new “rebels”.

And you need to read Capellanus, and as you read it, to see the manipulation in the pages. Maybe it was adopted because it had social value to blunt the negative behavior or the men of the time and turn it in a constructive direction.

But today it is only something that is used to provide advantage for women. And that advantage is often used at the expense of men, and furthermore, for the punishment of men, the social shaming of men, when women deem the men’s behavior or actions to be at the detriment of women. And they are allowed to be judge, jury, and executioner of their verdict. And no one ever challenges them.

And we begin by rejecting unilaterally, out of hand, “love” for the pack of lies it is.

So I say we use our position as influence peddlers, taste makers, of our day and time, and shame men, Mangina men, and White Knights as fools; toadies for women and their “love”. And make no mistake, that whole White Knight shit comes exactly from this book. We all should read “Treatise on Love”, deconstruct it, and expose it for the bullshit sham it is.

I have ranted this in the past. It is time for men to gain an entirely new consciousness, a new awareness, a entirely new set of constructivism abstracts on which to frame their thinking.

The constant whine, complaint, criticism of the manosphere is that is attacks “love”, it makes “love” impossible, it kills “love”.

And I say, no it doesn’t. It exposes the reality of the impossibility of “love” because “love” is entirely a manufactured ideal. And modern Feminism has brought about the recognition of the impossibility of it and rubbed it in the face of men. If you pine for it, it you whine about it, the end of it, the lack of it, then you deny the truth of it.

Modern life is entirely developed as a means to blunt the natural advantages that men have. This “love” is a further handicap, a weight on your shoulders, that limits your ability to use your advantage, physically, mentally, by women exploiting the emotional advantage that women have over men. She only has this advantage if you allow her to have it.

So discard it. It is religion in you that does not work to your advantage.

So yes, “They have a right to do anything that we can’t stop them from doing”.

But we have the capacity and the ability to make them pay for it.

In the end, and my life right now is living proof of this, they need us more than we need them. We want them; they need us. And the things that most women want, they get from us. And without the handicap of “love”, you can make them pay, and pay, and pay, until they fucking cry uncle.

What I find interesting is that since the Middle Ages, as evidenced in Cornelia’s words, we have collectively conflated male love with sexual desire as if they are inseparable, and to women’s ability to control that male “love” through a skillful cultivation of beauty. One might be forgiven for refusing to believe this is love at all, that it is instead the creation of an intense desire for sexual pleasure due to the call of beauty. Observation shows that sex-generated “love” does not necessarily lead to compatibility for partners across a broad range of interests, and may occur between people who are, aside from sexual attraction, totally incompatible, with little in common, which is why the relationship often goes so badly when there occur gaps in the sexual game.

What I find interesting is that since the Middle Ages, as evidenced in Cornelia’s words, we have collectively conflated male love with sexual desire as if they are inseparable, and to women’s ability to control that male “love” through a skillful cultivation of beauty. One might be forgiven for refusing to believe this is love at all, that it is instead the creation of an intense desire for sexual pleasure due to the call of beauty. Observation shows that sex-generated “love” does not necessarily lead to compatibility for partners across a broad range of interests, and may occur between people who are, aside from sexual attraction, totally incompatible, with little in common, which is why the relationship often goes so badly when there occur gaps in the sexual game.