Can a woman be chivalrous?

Chivalry is today seen as a mostly male obligation toward female beneficiaries. In the past there were exceptions showing that “chivalry” could be applied equally to women who demonstrated it.

Stripped of the usual gender conventions, romantic chivalry is nothing more than displays of altruism and generosity toward another human being. The sooner women start extending such “chivalry” toward men and boys, and calling it “chivalry,” the sooner we might call relationships reciprocal. Until then we will continue to see male-only chivalry by workers on the gynocentric plantation.

A few examples of ‘female chivalry’ follow, with dates:

Female chivalry

1792 “Mr. Burke remarked, that however the spirit of chivalry may be in the decline amongst men, the age of female chivalry was just commencing.”

1918 “Spenser, following Ariosto, laments the decay of female chivalry since the days of Penthesilia, Deborah, and Camilla.”

1938 “This tendency among women of making concessions to men for their inferior moral strength I would like to term “female chivalry.” It is chivalry in the strictest sense of the term because it makes concessions for the weakness of the opposite side. In a society which is so primitive that its women have not yet developed in their conduct with men this moral chivalry, no doubt the woman is an inferior and subordinate member, an object of masculine pity. But the moment she brings into play upon the field of our social behaviour her superior moral strength (manifested through the developments of her inherent powers of sacrifice, endurance and self-discipline) she not only qualifies herself for equality of treatment but records a moral victory of first magnitude over the opposite sex.”

Woman’s chivalry

1847 “It may be, too, that such pursuits belong to woman’s chivalry, in which she accomplishes tender victories, and with silken cords leads into bondage the stouter heart of man. Happy triumph: in which there is equal delight to the victor and the vanquished.”

1924 “There are poems of the human soul cut off from God by its loveleasness — the hell of separation of the finite self from the infinite; poems of the “white flame” of a greater love; woman’s chivalry towards woman ; woman’s chivalry towards man: and in the end, peace.”

1936 “Neuilly, but something — perhaps a woman’s chivalry to another woman — prevented her from doing it.”

Chivalric female

1864 “The order of Sisters of Charity, therefore, as constituted by St. Vincent de Paul, and whose deeds are known to the whole world, may be considered an aristocratic or chivalric female army of volunteers of charity, bound to short terms of service, but generally renewing their vows, and performing prodigies of usefulness.”

Chivalrous women

1857 “It must be confessed that the spectacle of those three chivalrous women, so magnanimous in face of an evil cause… preparing to plunge into the medley of battle, instead of remaining at a distance to watch the fortune of the fray, instead too of shutting themselves up in some luxurious dwelling there to await the intelligence of the result – but armed and mounted – with martial plumes waving over their heads, fire in their eyes and decision on their lips… could have no other effect than the most inspiring one over those who beheld it.”

1896 “For a lady is among other things a woman with a sense of chivalry, and a chivalrous woman uses her finer gifts to supplement the blunt honesty of her husband (if she is the happy possessor of an honest husband).”

1904 “The self-sacrificing chivalrous woman, with whom duty is a first consideration.”

1906 “Those chivalrous Women seem to be chosen instruments for the world’s betterment—all in the general economy of nature — evidence of growth which sometimes takes us by surprise and makes us sit up and think.”

1912 “Yes — women can he chivalrous! — women can live and die for a conviction! My terrible confession is made easier by your belief!”

1918 “to the free and chivalrous women of America.”

1919 “they called upon the free and chivalrous women of America to make these wrongs their own and, in so far as possible, to try to redress them, and to safeguard the future of the race by standing for the independence of historic Armenia.”

1920 “This mighty work of hospital redemption, now so nearly accomplished in all civilized countries, so appealed to chivalrous women that there seemed no end to the stream of incoming probationers.”

Chivalric woman

1897 “We are glad to know that such a noble and chivalric woman has her being among the toilers of the overwrought East End, and trust that her good deeds have not gone unrewarded.”

___________________

We live in a time now of great convenience, and if relationships are to mean anything going forward they will need to be based on some kind of reciprocal chivalry. And the good news is that men and women can demonstrate their brands of chivalry differently if they wish…. a ‘co-chivalry’ that can be respectful of similarities or differences as agreed between individual men and women.

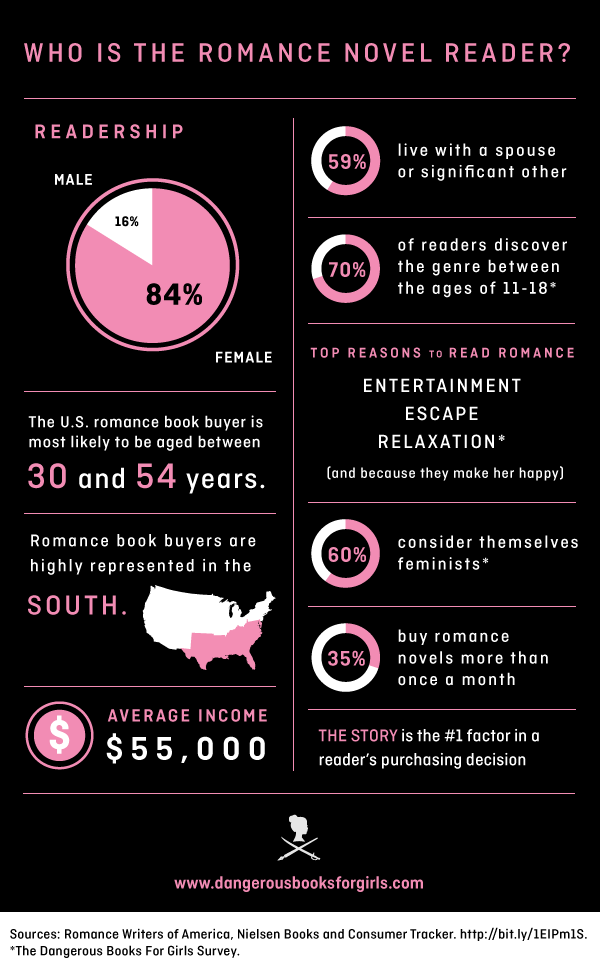

60% readers of romance novels consider themselves ‘feminist’

According to polls only 18% of U.S. women consider themselves feminist, however a whopping 60% of readers of romantic love fiction consider themselves feminist.

As detailed elsewhere on this website, this finding suggests a complicity between contemporary feminist aspirations and the courting trope first manufactured in medieval Europe.

Source:

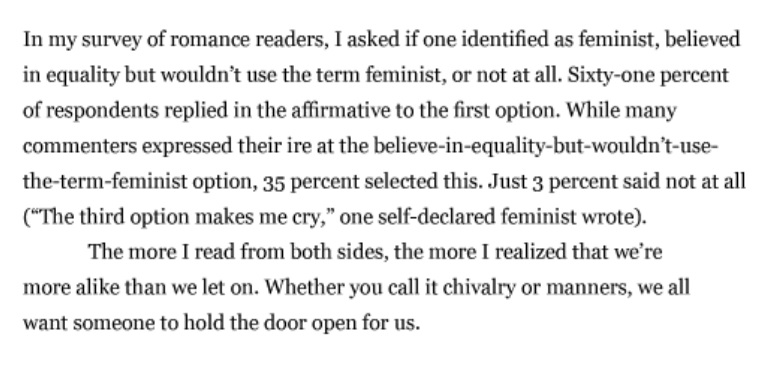

[1] The above info-graphic was compiled from a survey of 800 people and published in Dangerous Books For Girls: The Bad Reputation of Romance Novels Explained. The author adds this comment on the feminist question:

The Greek Titans: Images of Chaos

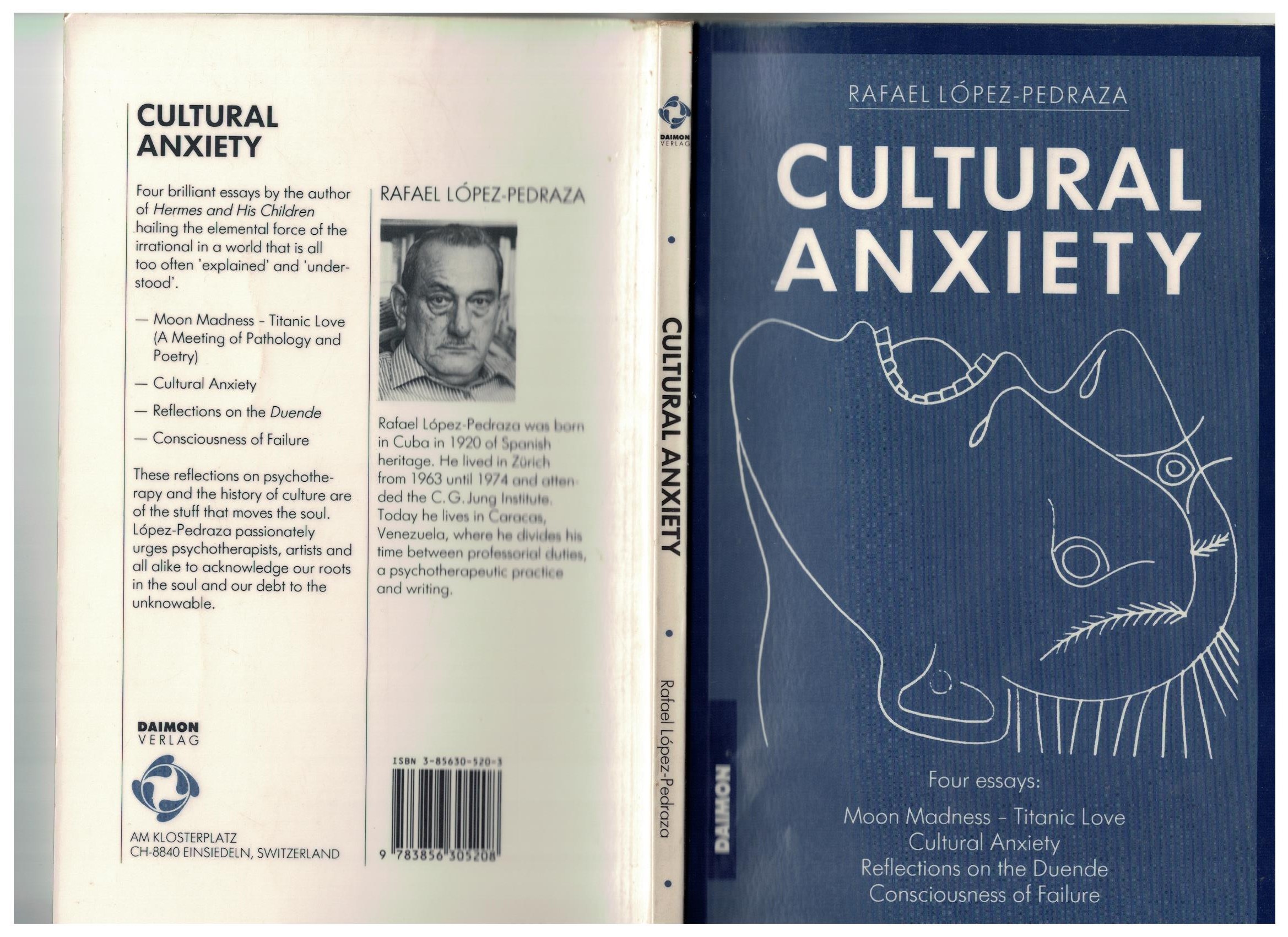

The following excerpt from Rafael Lopez-Pedraza’s excellent book Cultural Anxiety explores the mythical Titans as archetypal image of both pre- and post-modern chaos.

Lopez-Pedraza explains that archetypal forms – Zeus, Hera, Aphrodite, Demeter etc. – are exactly that, formed archetypal patterns. The Titans on the other hand are rough amalgams, poorly formed and shape-shifting entities who thrive in chaos and destruction. The image of the Titan exemplifies the postmodern chaos currently being unleashed on Western cultures. – PW.

[click on images to enlarge]

Below is the animation The Battle for Mount Olympus, a powerful portrayal of the battle between the archetypal Gods & Heroes and the Titans, capturing in symbolic form our present cultural dilemma.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=thxKvHulUgk

A brief critique of Jordan Peterson’s use of “Jungian” sources

The following thoughts on Jordan Peterson’s use of Jungian material were made in response to a comment from Bora Bosna at AVfM saying, “The cult of Peterson continues to grow.” While I generally appreciate Peterson’s thinking, and wish him well with his work and growing audience, I take issue with some of the intellectual source material he uses to build his arguments. – PW

____________________

Bora Bosna: “The cult of Peterson continues to grow.”

Surprising seeings he approaches his material via Classical Jungianism which is basically Jung and his immediate followers’ theories, much of which is formulaic, theoretically lame and debunked – though some of it good too. Unfortunately Peterson champions some of the lame stuff – eg. the writings of Erich Neumann, whose theories and writings (The Great Mother, and Origins and History of Consciousness,) have been thoroughly demolished by later, more rigorous Jungian thinkers.

There are two other schools of Jungianism that arose out of the classical school – the ‘Developmental School’ which blends psychoanalysis with Jungianism, and the ‘Archetypal School’ started by James Hillman who was the first Director of the first Jung Institute in Zurich. Hillman dreamed the movement forward, applying Occam’s razor to all the crap of the classical school and taking the really good stuff to another philosophical level.

Following the classical school is Peterson’s Achillies heel…. some of his presentations will not be taken seriously by the most brilliant in the Jungian field, even if students are starry-eyed. For example Peterson buys Neumann’s extremely gynocentric thesis The Great Mother in which he posits that mothers and women are symbols of an overarching feminine archetype that subsumes all the other archetypes, and in that book Neumann takes every scrap of symbolic material he can lay his eyes on and interprets it as mother – the Great Mother. Peterson follows this template exactingly.

Then there’s The Origins and History of Consciousness in which Neumann states bald faced that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny, an outrageous put-on that was nicely debunked (or rather demolished) by Archetypal Psychologist Wolfgang Giegerich’s essay entitled Ontogeny = Phylogeny? A Fundamental Critique of Erich Neumann’s Analytical Psychology. Despite that powerful critique, Peterson continues to promote Neumann’s thesis, and also advertises Origins and History of Consciousness in his recommended reading list.

There are other conceptual issues in classical Jungianism, such as the restatement of traditional gender-roles that accumulated under Jung’s descriptions of Animus and Amima which divides an enormous amount of psychological phenomena into strictly masculine and feminine boxes, and applies those boxes to real men and women. Add to that what classical Jungian’s call “the Feminine” – a big basket of bloated gynocentric concepts (eg. that Eros and all the other treasured psychological phenomena are feminine, and all the oppressive, violent and cold intellectual stuff is ‘the Masculine’) – all of which leaves us with a bunch of false stereotypes instead of what we might call phenomenological archetypes.

Then we have the classical concept of archetype, which utterly falls the test of logic with its reference to a noumenal archetype per se vs. the phenomenally presented archetype. The fact is we can only refer to the phenomenal archetype, that which manifests itself in images. The “noumenal” archetype per se cannot by definition be presented so that nothing whatsoever can be posited of it. In fact whatever one does say about the archetype per se is a conjecture already governed by an archetypal image. This means that the archetypal image precedes and determines the metaphysical hypothesis of a noumenal archetype. So, let us apply Occam’s razor to Kant’s noumenon. By stripping away this unnecessary theoretical encumbrance to Jung’s notion of archetype we restore full value to the archetypal image.’ (Hillman 1971).

Listen to Peterson try and define what an archetype is here, and note his nervous leg and difficulty in describing what it is – eventually conceding it is a “fuzzy word”: https://youtu.be/NOzjfqO6-K8?t=1h49m27s

One of the things that makes the notion of archetype fuzzy is the classical Jungian claim that some things are archetypal whilst other things are not archetypal – which is a cause of great confusion. A better way to conceptualize archetype is that any and all images can be considered archetypal, which does away with the artificial dividing of those images which are, and those which are not archetypal. The following from James Hillman captures this approach:

Any image can be considered archetypal. The word “archetypal” … rather than pointing at something archetypal, points to something, and that is value. By archetypal psychology we mean a psychology of value… Archetypal here refers to a move one makes rather than a thing that is.

Emphasizing the valuative function of the adjective “archetypal” restores to images their primordial place as that which gives psychic value to the world. Any image termed “archetypal” is immediately valued as universal, transhistorical, basically profound, generative, highly intentional, and necessary. [Archetypal Psychology]

If we use the more precise definition of archetype as a valuative approach toward all images then it is not fuzzy at all.

All of that said, I still highly value Jung (I have his collected works and read many times) and post-jungian writers, but Occam’s razor is needed so as not to lead people with flawed conceptual maps – especially by Peterson who uses classical Jungian frameworks to reach a big audience. He would do well to brush up on more rigorous Jungian thinkers like those from the so-called Archetypal Psychology school.

I could go on critiquing classical Jungian concepts – which informs Peterson’s views of history, psychology, gender relations and religion – but I’ll leave it there. I actually like a lot of what Peterson is saying and doing, including his hypomanic style of presentation which is really engaging, so I’m a fan…. but not a fan in the style of his younger students who seem to be worshiping him as a modern day Jung…… which is not far off the mark. I guess people need someone to look up to, and they could do a lot worse than Jordan Peterson.

Peterson is doing some valuable work in reviving the importance of imagination, religious frameworks, and unpacking postmodernism and the huge problems it has unleashed on human cultures. For that we can be thankful.

See also: The Gynocentrism of Jordan Peterson

Sadomasochism and courtly love

The following excerpt, translated from the French title The Meaning of desire – sado-masochism and Courtly Love by Emmanuel-Juste Duits, explores the considerable overlap between sadomasochism and courtly love. If anyone has a better translation please feel free to submit it.

__________________

Sadomasochistic dominatrix and courtly dominatrix

Wearing leathers, her long black hair tied by a braid, her legs sheathed, hard and inquisitive glance, surrounded by the colors of the night, this image is represented by the dominatrix.

What common features would she have with the ‘courtly lady,’ of a gentle and wise appearance, with a high hat surmounted by a veil, hidden by her long robe embroidered with pink and turquoise hues?

Imageries opposed, or similar realities?

In courtly love and SM it is easy to see the similarity of the terms used, symbolic gestures, and even certain practices. The dominatrix officiates in a “dungeon,” a space furnished with the often Gothic character where arched windows open, with walls of stone, impressive chains, iron doors. She receives servants and, just as in courtly love, the classical sexual act is just out of reach. Inaccessibility and distance are law.

But let us begin with the trait which gives its title to these two queens: domina /dominatrix. Why ? By their haughty character and magical power (mana), they dominate man who readily recognizes himself as a vassal. The first troubadour, Guillaume IX, one of the most powerful lords of the kingdom, called himself a vassal of his lady. The domnei (the chivalrous male lover) is admitted during a kneeling ceremony where he receives a ring as a pledge of fidelity and absolute obedience.

It thus becomes a genuine act of serving (in the medieval sense), ironically reversing the older chivalrous act of force and instituting a new male submission by the Middle Ages! But what does female domination sung by the minstrels consist of? What does this word hide, far beyond a capricious will and the arbitrariness of desires? It is evident that the courtly lady develops moral and intellectual qualities which are far from evoking sadism and the violence unleashed by tyrannical instincts. She is supposed to be cheerful, welcoming, and witty. This may also be appropriate, in some respects, to the real dominatrix who demonstrates self-control and respect for her subjects.

What is the fascinating virtue that invests the feudal overlord (suzerain)?

Patriarchal societies advocate a so-called “natural” order which contains a set of coherent values, which are linked together and enslave us to the family, to a warrior and vengeful God, to the father, to the country, and to the enterprise. And also a supposedly natural place is there attributed to woman. According to this perspective woman is passive in essence, which is expressed in her sexual posture but also in her “intuitive and receptive” mind and in her social role which consists of the conservation of society and the exclusive breeding of children in the tradition. How all this goes together!

But the domina, however, has enough inner strength to overthrow this aesthetic prescription. Only against the inertia of a medieval society imbued with manly values – ??or against a modern society that insidiously demeans it – does it come to the fore and assert itself as sexually and mentally active. Whether it is the “black” domina of SM or the “white” domina of the courtly love, it escapes the function devoted to women “by nature and by God”. Neither mother, nor good wife, nor receptacle of penetration. Neither soft nor fragile, nor manipulative, demanding, and tyrannical.

Today’s society spreads the image of such free, strong and unleashed women, as if a new femininity was dreaming on the fringes of our collective consciousness. In the teenage version, these are the Spice Girls and the Amazons in Hard Rock Leather, or Catwoman and other practitioners of the martial arts. Ideal for millions of girls who, for now, do not seem to assume this girl’s power. Moreover, what should such a slogan hide to be truly revolutionary? The modern woman risks confusing liberation, especially a positive but limited external one, with psychological, erotic and spiritual liberation.

[……..]

[It] has the merit of showing the radical difference between the purely material independence of the wonder-woman serving a social function, and dominating it, which rejects most norms of productive and sexual “utility.” The true dominatrix fascinates not by her brutality nor by her sadism, but by her intellectual, erotic and aesthetic autonomy. She sculpts and invents her own norms, and attributes to herself the decision and the action – without necessarily denying them to men, even if a fundamentally amorphous character would characterize it, according to the founder of Scum.

This interior and mental power constitutes the focal point of our two figures of dominas. They are also cruel. When Lancelot returns from a thousand sufferings, his body broken and his wounds exposed, Guinevere pretends to reject him because he hesitated for a few moments before one of his most mortal trials. At their reunion, these adulterous lovers of the Arthurian cycle finally spend a night of love and their sheets are covered with the blood of the knight who cut a finger by forcing open the grid that separated him from his mistress … Thus, the courtly eroticism has sometimes taken a cruel turn. Guillaume IX, the first troubadour, tells a very edifying story. Disguised as an innocent clerk, the hero of the song crosses two noble ladies, married moreover, who find him to their taste and collect him in their lodgings. He pretends to be mute. Here is what Agnes says to Ermessen:

“We have found what we are seeking. My sister, for the sake of God let us lodge him, for he is truly mute and never by our plan will be known. So the hero finds himself in the ladies company, fed capons near the stove, thinking “When we had drunk and eaten, I stole myself as they pleased. Behind my back they brought me the wicked cat and felon; One pulled him along my side to the heel dragged by the tail without waiting. She pulled the cat and he clawed at me: they made me more than one hundred wounds.” Agnes to Ermessen, “Sister, he is mute, it is veryclear; let us prepare for the bath and take advantage of his presence.” “Eight days and more I remained in this furnace. I took them as many times as you will hear: One hundred and eighty-eight times (…) I cannot tell you my pain at all.”

We shall not count all the courtly songs in which the lady finds herself cruel, pitiless, capricious, mocking, and in which the poet seems to delight in suffering inflicted by the woman whom he adores. Lancelot, the best of knights, will have to suffer public humiliation: to obey his queen Guenièvre, he will behave cowardly in the biggest tournament of the country for a whole day, wiping away the least gossip and taunts of the least grooms, and weak riders. Like Sacher-Masoch, loving implies accepting suffering, which is the pledge of true love.

Courtly love – a precursor of SM?

If the dominatrix inflicts suffering, the courtly lady also submits her servant to various trials: show her valor in the tournament if it is a knight, restrain your primary sexual desires, sing, make beautiful verses, respect the Secret, take many risks to stealthily observe her when she strips herself and goes to the bath, traveling alone and undergoing severe deprivations to increase its valor

In SM as in courtly love, one recognizes the classical scheme of the work in the dark, the ego being worked over by the confrontation with his fears, the tests involving a physical or moral danger. According to Jung, this phase is to be found in any evolutionary process, whether it be therapy or alchemy, the “matter” of the soul is to be tarnished and then melted with some violence.

To learn to be silent, to wait and to hold one’s desires, to wander, to feel alone, to suffer in one’s flesh, to enjoy only a few caresses and many blows, all this seems necessary to those who wish to acquire a little individuality! But to fulfill this individualizing function, the tests must have a profound meaning: they correspond in particular to the meeting of elements (tests linked to water, fire, earth, air – suspension, vertigo …), (Black, silence, abandonment, dismemberment, suffocation …), the overthrow of social values ??and the image of oneself (one finds in this class of the transvestite, the inversion of roles, the boss playing the slave … ).

Once encountered, trials need to be understood in order to integrate into one’s person: hence the role of the possible therapist and verbalization, and the need to know symbolism. By his poetic asceticism, the knight-troubadour will attain, as the initiate, a modified state of consciousness. Is this not what many songs testify to? Raimbaut d’Orange (1147-1173) has no suspicion of being taken for mad when he evokes this internal metamorphosis:

“Here is the opposite flower on the rocks among the mounds.

Flower of snow, ice and jellies,

Who bites, who tightens and slings. (…)

For in me all is reversed,

And the plains seem to me mound,

The flower springs from the frost,

The hot in the flesh of the cold slice,

The storm becomes singing and whistles

And the leaves cover the stems.

So glad I am that I do not seem to be baseless in any place. ”

Within the middle classes of our society, the possible dangers are fortunately more limited than in the twelfth century. The brigands swarm less than in the medieval forests, and the suburbs do not compete with the court of miracles, in spite of our “savages.” The voyages are made in the warmth of the TGV, and do not allow us to appreciate either the dark night of the great forests, nor the disturbing howling of the animals, the bite of the cold, or the warmth of the horse. We are impoverished in “real” feelings, far from a formative confrontation with reality.

Apart from a few medical examinations and the pitiless irruption of the illness, which reminds us of the essential realities, we float in a rather abstract universe of social appearances. Some prefer to tear the veil and seek the meeting of elements by practicing sports, mountaineering, hang-gliding, diving … others find the ardor and ethics of combat by the martial arts. Finally, the sadomasochist makes it possible to taste somewhat forgotten sensations, and to return to reports that are both more refined and rough, perhaps more true and symbolic than what we experience under our social masks.

Thus the trials demanded by courtly love presented themselves in a less bloody light than in SM because medieval society itself had enough risks and dangers. Obviously, the excretory aspect that can be associated with SM – uro and scatophily – remains totally foreign to the courtly universe. The courtly love demands lose in intensity what they gain in extent. They involve a global character: the aim is to seek constant improvement and to modify one’s behavior on a daily basis.

The sadomasochistic game, for good reason, tends to unfold in a delimited field, with its instruments, its world, its well-defined witnesses . Once the session is over, the adept risks becoming a citizen again, sometimes an excellent cog in the company, an efficient executive or a faithful husband. SM is generally compatible with

Standards of liberalism; Once again, it resembles a therapy, with similar advantages and disadvantages: falling from anxiety and better adaptation to the business or family!

If it is true that the DM allows for some improvement of self, it does not push to fight for political justice. On the other hand, courtly love is in conflict with social integration. Many poems of troubadours could be discovered chanting a dispute of the religious or political order, especially from the Albigensian crusade. Bernart de Rovenac (1242-1261) accuses the lords (“I have a great desire to make a sirventès, powerful and cowardly men … although it seems madness to you, I am more pleased to blame you by telling you the truth – that is to say, pleasant things while lying … “); Guilhem Figuera (1215-1240) attacks the Church (“(…) Deceitful Rome, who are from all evil the guide, top and root, so that the good king of England was betrayed by you … Rome Rome, to weak men, you eat away the flesh and the bones and guide the blind with you into the pit … “). As for Peire Cardenal, he addresses a very insolent petition to the creator:

“A new sirventes I want to begin

that I will recite on the Day of Judgment to him

who created me and formed of nothing

If he thinks I am reproaching myself for something …

and I will make a good proposal

that you bring me back from where I left on the first day

or that you forgive my sins

because I would not have committed them if I was not born (…) ”

Courtesy requires politeness, generosity, hence refusal of injustice. The appearance is beautiful only if the inner life strives towards the ideal. As an alchemist can succeed in the Great Work only if, in addition to his technical competence, he possesses moral qualities, so a troubadour is worthy of love only if, in addition to beautiful verses, he succeeds a few great gestures. The knight must correct the wrongs and fight against errors, false pretenses, both in and around the world. Here we find the socially subversive aspect of courtly love.

The difference is therefore essential between sadomasochism and courtly love. The domnei pursued a high, almost superhuman ideal, symbolized by the Grail and the Crusade, or by a state of poetic and mystical creation. The pain was on the way an inevitable companion, but it was not a goal, and was not inflicted “for pleasure.” The artist who has to struggle to perfect his creation and the knight who crosses distant lands

necessarily confront a thousand sufferings. They aim at a result and a work that transcends their individuality and can be offered to others. Their project is both personal and altruistic.

The courtly scene assumed its full meaning when it was accompanied by an effective verification of the acts and creations of its various protagonists. Despite the physical distance, it involved a mutual “surveillance”, by interposed reputation. A noble knight, a renowned lady or a well-liked troubadour were supposed to perform actions and works of brilliance, worthy of being reverberated from castles in progress. It was a question of the two lovers fighting against social and psychological baseness, of integrating the elements and the many facets of the human soul (masculine-feminine, hardness-softness, dependence-independence …), and finally to dis-identify from the social comedy.

In some respects, one might compare the gradual initiation of courtliness with that of master-disciple in the secret schools of the East. In courtly love as in esoteric schools, the meaning of these various tests, in addition to the magical integration of the elements, will be to find one’s true being. It is only after this work of inner self-esteem that authentic encounter with love is possible. There is no other way to isolate the essential love – that which is addressed to the whole person of the beloved, to her soul, if you will – to eliminate all that is addressed to what this person is not, that is to say, synonymous with his physical details.

And there can be no lovers of joy absolutely purified other than this desire which is exalted and satisfied with the mere presence of the beloved, the only feeling of the spiritual communion existing between her and him and whose embrace of looks is indeed the sign. Courtly love, like evolutionary SM, a complete loving path, with its own rituals and a form of pleasure, is quite different from the so-called “normal” sexual games.

These approaches prove that love and the couple can give themselves an end in addition (or beside) to procreation. They draw attention to one aspect of love relations, particularly revolutionary for the current mentality: the incandescence of pleasure achieved without recourse to the sexual act.

Today, when the classical aspect of sexuality is over-emphasized in relation to sensuality and erotic play, this will surprise. It would no doubt be necessary to recall in our “liberated” period a reality: relationships other than penetration are possible and satisfying, even for straight men! Courteous love like the SM invites us to question the distinction between the sensual and the sexual, and the new forms of relationships open to us. But what precisely was the love of courtly love, and where did it come from? We shall see that it remains a historical enigma.

Chivalry: a sexist expectation of the medieval mind

The following is an example of gynocentric etiquette, alive and thriving in the expectations of many women (and men) today.

See also: Gynocentric etiquette for men

Early mentions of the phrase “Romantic love” in English literature

Romance (n.)

c. 1300, romaunce, “a story, written or recited, in verse, telling of the adventures of a knight, hero, etc.,” often one designed principally for entertainment, from Old French romanz “verse narrative.” This sense obviously included the love aspect of adventures; Lancelot and Guinivere, Tristan and Iseult, etc.

c. 1600s romaunce or romance narrowed to “a love story, the class of literature consisting of love stories and romantic fiction.”

c. 1700 extended as ‘romantic love,’ alternatively rendered ‘romantick love.’

The meaning of the phrase romantic love is a tangled one, however some of the first uses of it in English can be traced back to around 1700 when it was coined to refer to Don Quixote and his adventures in chivalric love. Suffice to say the medieval trope is there at the beginnings of this English phrase. Below are some early examples (and descriptions) of romantic love in English literature. Note the continuity of courtly love themes from the Middle Ages such as belief in the purity of women and their moral elevation above men, along with male supplication, chivalry, long-suffering, and of the ultimate extravagance of love. Below is a history of the english phrase ‘romantic love,’ which had equivalent counterparts in older French and German languages. The phrase and concept of romantic love is often wrongly conflated with the romantic period or “romanticism” which spanned from 1798 — 1750; however the phrase romantic love is clearly older and independent of the romantic period, as demonstrated in the samples below from almost a century prior to romanticism (eg. beginning of 1700s):

_________________________________________

Romantic love

1700:

“Many men being still of the opinion that the wonderful declaration of Spanish bravery and greatness in this lost century may be attributed very much to his carrying the jest too far, by not only ridiculing romantic love and errantry, but by laughing them also out of their honour and courage.” [The History of the Renown’d Don Quixote de la Mancha, 1700]

1705:

May for their sakes thier women are bullies prov’d, who walk the streets with wild romantick love, and cuckold their husbands in each others’ sight. [The Dutch Deputies. A Satyr. Quid non Batavia Fecit]

1720:

“And do you think, said his father changing his tone, I shall have the complacence to approve this romantic love of yours…” [A Select Collection of Novels: Don Carlos]

1734:

“Fill’d with romantick love Sir John began to sigh,

Thought he must love, but knew not what, nor why,

Still he read on, and still encreas’d his flame,

And found that each knight-errant had his dame

What shou’d he do alone without a fair?

Just at the nick o’ time, ‘with wond’rous air,

Sultan with broom was sweeping down her stair,

Sir John was smitten with a pleas’d surprize,

And face imaginary charms arise,

New beauties at each look their sweets diffuse,

Here the white lily, there the blushing rose;

In short—to Sultan he reveal’d his love,

Which the coy cunning reply did improve,

‘Till with intrigue he stole his fatal curle,

To sucky ty’d for better and for worse.

Soon marry’d, the succeeding honey-moon,

As it too often proves, was over soon;

He views his wife, not at her view’d his maid,

The lilies vanish, and the roses fade;

Discords, (as discords will in marriage rise)

From morn to evening fill the boufe with noise:

Poor Ladyship, to hinder wars to come,

Renews the operation of her Broom;

The Knight too late convinc’d by aching side,

She who could brush his hairs, could brush his hide.” [The London Magazine, Or, Gentleman’s Monthly Intelligencer]

1737:

“Farewell, farewell forever. She left me, with how much concern upon my heart, as it was beyond what I ever felt, it is beyond what I can ever express. Tho’ I was assur’d her reproach was unjust, yet from the principles of affection that gave occasion to it, it affected me. I struggled long between romantic love and prudent conduct: one day I resolv’d to fling myself at her feet the next, and give a proof of my love by ruining myself in marriage ; but the next I thought it better to see her Father again, and strive if…” [The London Magazine; Or, Gentleman’s Monthly Intelligencer, 1737]

1741:

“But I think the tragedy may receive a wonderful force, should its authors, without minding that giddy Romantic Love which makes such havoc in their plays, follow only the true philosophic Ideas of antiquity.” [An historical and critical account of the theatres in Europe, Luigi Riccoboni – Printed for T. Waller, 1741]

1742:

“And where’s the diff’rence twixt old age,

and youth worn out in its first stage,

No longer to apologize,

ye husband’s aged, rich and wise,

Dread twice to court the nuptial state,

and from the sequel mark your fate,

Ye Quixotes in romantic love,

Platonic cuckoldom improve.”

[A Wife and No Wife: the Mad Gallant, an Humorous Tale of Lunacy, Love and Cuckoldom]

1749:

“This novel is altered from one published in the year 1762 The Author, perceiving many material defects in the original work, particularly that the story was too simple to be very interesting, too concise to admit of much exemplification of character, and too much in the usual strain of romantic love.” [The Monthly Review, Volume 53, Ralph Griffiths, George Edward Griffiths, 1749]

1761:

“There is no resisting the impetuosity of romantic love. Like enthusiasm it breaks through all the restraints of nature and custom and enables, as well as animates its votaries, to execute all its extravagant suggestions ” [The World – by Adam Fitz-Adam, by Edward Moore, publishe by R. and J Dodsley 1761]

1773:

“The adventures of the Spanish knight [Don Quixote] were written to expose the absurdities of romantic chivalry, so those of the English heroine were designed to ridicule romantic love, and to show the tendency that books of knight-errantry have to turn the heads of their female readers.” [The Critical Review, Or, Annals of Literature, Volume 35, W. Simpkin and R. Marshall, 1773]

1776:

“Reading books of extravagant poetry raises corresponding doubt’s in the mind as they paint all the passions immoderate. Tragedies, such as they frequently are; books of romantic love, and which is fifty times worse, books of romantic intrigues, all tend to disturb the breast of the tender fair one.” [The Lady’s Magazine; Or, Entertaining Companion for the Fair Sex, Appropriated Solely to Their Use and Amusement, Volume 7, G. Robinson, 1776]

1777:

“Romantic love seems to be almost peculiar to the latter ages. This passion may perhaps be traced up to that spirit of courtesy and adventure which arose from circumstances peculiar to feudal government, distinguished all the institutions of chivalry, gave birth and form to the old romance, and consequently to the new, and to this day influences in a perceptible degree the customs and matters of Europe.” [Essays on the Nature and Immutability of Truth, 1777]

1777:

“In this correspondence the two friends encourage each other in the [……] notions imaginable. They represent romantic love as the great important business of human life, and describe all the other concerns of it as too low and paltry to merit the attention of such elevated beings, and fit only to employ the daughter of the plodding vulgar.” [The Universal Magazine of Knowledge and Pleasure, Pub. for J. Hinton, 1777]

1787:

“The romantic love, peculiar to the ages of chivalry, was readily united with the high sentiments of military honour, and seem to have promoted each other.” [An Historical View of the English Government From the Settlement of the Saxons in Britain to the Accession of the House of Stewart]

1787:

“The customs of duelling, and the peculiar notions of honour, which have so long prevailed in the modern nations of Europe, appear to have arisen from the same circumstances that produced feudal institutions: That same institution produced the romantic love and gallantry, by which the age of chivalry was no less distinguished…” [The Critical Review, Or, Annals of Literature, Volume 63, 1787]

1798:

“I readily grant that in former times this veneration for personal purity was carried to an extravagant height, and that several very ridiculous fancies and customs arose from this. Romantic love and chivalry are strong instances of the strange vagaries of our imagination, when carried along by this enthusiastic admiration for female purity; and so unnatural and forced, that they could only be temporary fashions. But I believe that, for all their ridicule, it would be a happy nation where this was the general creed and practice.” [Proofs of a Conspiracy against all the Religions and Governments of Europe, by John Robison, Philadelphia, 1798]

The evolution of gynocentrism via romance writings

The sexual relations contract encoded in courtly love fiction was at first celebrated among the upper classes, but made its way by degrees eventually to the middle classes, and finally to the lower classes – or rather it broke class structure altogether in the sense that all Western peoples became inheritors of the customs of romantic love regardless of their social station.

Today the romantic novel is the biggest grossing genre of literature worldwide, with its themes saturating popular culture and its conventions informing politics and legislation globally.

Upper-class beginnings

The three-stage evolution of romantic love saw its first chapter begin in 12th century France. Eleanor of Aquitaine and her daughter Marie De Champagne together elaborated the military notion of chivalry into a notion of servicing ladies, a practice otherwise known as ‘courtly love.’

Courtly love was enacted by minstrels, playrights and troubadours, and especially via hired romance-writers like Chrétien de Troyes who wrote stories to illustrate its principles. Under the continuing guidance of Marie it was elaborated into a code of conduct by Andreas Capellanus in his famous tract titled ‘De amore’ (in English The Art of Courtly Love).

The aristocratic classes who developed this trope did not exist in a vacuum. The courtly themes they enacted would most certainly have captured the imaginations of the lower classes though public displays of pomp and pageantry, troubadours and tournaments, minstrels and playwrights, the telling of romantic stories, and of course the gossip flowing everywhere which would have exerted a powerful effect on the peasant imagination.

We cannot know for certain but it is likely that those of even lower classes adopted some assumptions portrayed in the public displays of courtly love, such as the importance of chivalrous behavior toward women and perhaps a belief in the Lady-like purity and moral superiority of women. Lucrezia Marinella provides just such an example of Venetian society from the year 1600:

It is a marvelous sight in our city to see the wife of a shoemaker or butcher or even a porter all dressed up with gold chains round her neck, with pearls and valuable rings on her fingers, accompanied by a pair of women on either side to assist her and give her a hand, and then, by contrast, to see her husband cutting up meat all soiled with ox’s blood and down at heel, or loaded up like a beast of burden dressed in rough cloth, as porters are.

At first it may seem an astonishing anomaly to see the wife dressed like a lady and the husband so basely that he often appears to be her servant or butler, but if we consider the matter properly, we find it reasonable because it is necessary for a woman, even if she is humble and low, to be ornamented in this way because of her natural dignity and excellence, and for the man to be less so, like a servant or beast born to serve her.

Women have been honored by men with great and eminent titles that are used by them continually, being commonly referred to as donne, for the name donna means lady and mistress. When men refer to women thus, they honor them, though they may not intend to, by calling them ladies, even if they are humble and of a lowly disposition. In truth, to express the nobility of this sex men could not find a more appropriate and fitting name than donna, which immediately shows women’s superiority and precedence over men, because by calling women mistress they show themselves of necessity to be subjects and servants.1

Middle class adaptation

The Victorian era saw the birth of mass novel writing, with much of it written by female authors. Whatever aspirations women had to romantic love in previous centuries, it was now actualized in writings by and about middle-class women, and the themes penned would become ritually enacted, ie. lived, by millions. This development is viewed by some researchers as marking a liberating revolution for middle class women.

Victorian peoples loved the traditional medieval romances of knights and ladies and they hoped to regain some of that noble, courtly behaviour and impress it upon the people both at home and in the wider empire. A new approach however saw it pitched beyond the upper classes to a larger group of people.

In her book Male Masochism, Carol Siegal2 gives an overview of Victorian women’s novels by focusing on the continuation and evolution of the romantic love themes found in medieval romances:

“A great deal of what [Victorian] women’s literary works had to say about gender relations may have been as disquieting as feminist political manifestos, and ironically so, in that the novels seem most anti-male in the very places where they most affirm a traditionally male vision of love. While women’s lyric poetry tended to reverse the conventional gender roles in love by representing the female speaker as the lover instead of the object of love, women’s fiction most frequently reproduced the images, so common in prior texts by men, of the self-abasing male lover and his exacting mistress. For example, in Wuthering Heights, Heathcliff declares himself Cathy’s slave; in Jane Eyre, Rochester’s desire for Jane is first inspired and then intensified by his physically dependent position; in Middlemarch, Will Ladislaw silently vows that Dorothea will always have him as her slave, his only claim to her love lies in how much he has suffered for her. In several Victorian novels by women, men must undergo quasi-ritualized humiliation or punishment before being judged deserving of their lady’s attention. For instance, in Olive Schreiner’s Story of an African Farm, the fair Lyndall condescends to treat her admirers tenderly after one has been horsewhipped and the other has dressed himself in women’s clothes to wait on her. Although Victorian women’s novels do explore the emotional insecurities of the heroines, their apparent self-possession is also stressed, in marked contrast to their lovers’ displays of agony, desperation, and wounds.”

Siegal suggests that male masochism and the dominatrix-like behavior of women in these writings is continuous with courtly love literature from the Middle Ages. And whilst some libertines self-consciously chose their lowly position in relation to women, the men described in Victorian women’s novels lacked such volition:

“These texts also insist that the true measure of male love is lack of volition. While the heroines make choices that define them morally, the heroes are helplessly compelled by love, and not judged to love unless they are helpless. In this respect Victorian women’s fiction recovers the ethos so often expressed in medieval courtly romance that love must be “suffered as a destiny to be submitted to and not denied.” It also departs from the conventions of medieval romance in describing the helpless submission to love as an attribute of true manliness, and thus Victorian women’s fiction directly attacks the degeneration of chivalry into the self-conscious and controlled “gallantry” of eighteenth century libertines.”

Those who have read medieval romance literature will agree with Siegal that the sexual relations contract embedded in Victorian Romance novels provides the continuation of a medieval trope, and not a fresh vision generally speaking. It is an example of pastiche.

To be sure there are new elements in the Victorian novel, such as the stronger emphasis on emotion and the relaxing of class distinctions, but we are not dealing with a new animal in terms of larger trope structure, i.e. it is more like a new costume for an old play.

Said another way, the essence of the feudal relationship was extracted from the medieval class system in which it was born, and applied by authors of the Victorian era to people of the middle classes. With a passage of time and a further dissolving of class distinctions to which this trope might apply, it would be eventually applied to all people – class codes be damned.

The medieval structure in question is one we might call sexual feudalism. It is symbolized, for example, in the marriage proposal which sees men of any class go down on one knee – a ceremony originally intended for a feudal relationship contract in medieval times.

C.S. Lewis referred to the transfer of the feudal contract into intimate relations as “the feudalisation of love,” making the observation that it has left no corner of our ethics, our imagination, or our daily life untouched. And perhaps more importantly this sexual feudalism – or romantic love as it is popularly called – no longer relies on a feudal society or class structures for its existence.

Taking an earnest look at the power wielded by protagonists in the Victorian woman’s novel, and of the novel’s real-world consequences for women, Nancy Armstrong3 observes that the sexual contract can overrule the social contract, and that love can be the most powerful regulating law between two parties – a possibility that appears little considered by feminist writers.

Adaption by all levels of society

Romantic love today is the great leveler, smashing all class distinctions in its path. Women of low means can marry men of high station (and visa versa) because the love contract is capable of overruling the social contract. While there are literally millions of novels and movies that display feudalistic love overriding the social contract, the movie Pretty Woman, featuring Richard Gere and Julia Roberts, will suffice as a modern example:

Edward Lewis, a successful corporate raider in Los Angeles on business, accidentally ends up on Hollywood Boulevard in the city’s red-light district, after breaking up with his girlfriend during an unpleasant phone call. Leaving a party, he takes his lawyer’s Lotus Esprit luxury car, and encounters a prostitute, Vivian Ward. He stops for her, having difficulties driving the car, and asks for directions to Beverly Hills. He asks her to get in and guide him to the Beverly Hills Regent Hotel, where he is staying. It becomes clear that Vivian knows more about the Lotus than he does, and he lets her drive. Vivian charges Lewis $20 for the ride, and they separate. She goes to a bus stop, where he finds her and offers to hire her for the night; later, he asks Vivian to play the role his girlfriend has refused, offering her $3000 to stay with him for the next six days as well as paying for a new, more acceptable wardrobe for her. That evening, visibly moved by her transformation, Edward begins seeing Vivian in a different light. He begins to open up to her, revealing his personal and business lives.

Edward takes Vivian to a polo match in hopes of networking for his business deal. His attorney, Phillip, suspects Vivian is a corporate spy, and Edward tells him how they truly met. Phillip later approaches Vivian, suggesting they do business once her work with Edward is finished. Insulted, and furious that Edward has revealed their secret, Vivian wants to end the arrangement. Edward apologizes, and admits to feeling jealous of a business associate to whom Vivian paid attention at the match. Vivian’s straightforward personality is rubbing off on Edward, and he finds himself acting in unaccustomed ways.Clearly growing involved, Edward takes Vivian in his private jet to see La Traviata in San Francisco. Vivian is moved to tears by the story of the prostitute who falls in love with a rich man; after the opera, they appear to have fallen in love. Vivian breaks her “no kissing on the mouth” rule (which her friend Kit taught her), and he offers to put her up in an apartment so she can be off the streets. Hurt, she refuses, says this is not the “fairy tale” she dreamed of as a child, in which a knight on a white horse rescues her.

Meeting with the tycoon whose shipbuilding company he is in the process of “raiding,” Edward changes his mind. His time with Vivian has shown him a different way of looking at life, and he suggests working together to save the company rather than tearing it apart and selling off the pieces. Phillip, furious at losing so much money, goes to the hotel to confront Edward, but finds only Vivian. Blaming her for the change in Edward, he attempts to rape her. Edward arrives, punches him in the face, and throws him out.

With his business in L.A. complete, Edward asks Vivian to stay one more night with him — because she wants to, not because he’s paying her. She refuses. On his way to the airport, Edward re-thinks his life and has the hotel chauffeur detour to Vivian’s apartment building, where he leaps from out the white limo’s sun roof and “rescues her,” an urban visual metaphor for the knight on a white horse of her dreams.4

The trope of romantic love is ubiquitous and pervasive through all levels of Westernized culture, and is rapidly infusing into remaining pockets of Asia that had been historically secluded from its influence. Romantic love is the number one selling genre in literature, movies and music globally – a testament to its all encompassing power.

The fact that women have been front-and-center in crafting and promoting this medieval “love” contract flies in the face of women’s presumed powerless in the world. The two-spheres approach underlining powers unique to males and females is at play, and while only 1% of males traditionally controlled the political sphere, 100% of women possess the leverage of romantic love in the relational sphere. Further, I would go so far as to claim the political sphere governed by that 1% of men is now so captivated by the dictates of romantic love that its mission has become synonymous with the enactment of chivalry, both in social project spending, and in law.

The old saying is “Love conquers all.” However the author of that phrase had in mind a very different kind of love from the all-conquering power we today refer to as romantic love, and women have played a pivotal role in bringing the later to bear.

Sources:

[1] Lucrezia Marinella, The Nobility and Excellence of Women and the Defects and Vices of Men (1600) Translated by Anne Dunhill, Published by University of Chicago Press

[2] Carol Siegal, Male Masochism, Indiana University Press, 1995 (pp. 12-13)

[3] Nancy Armstrong, Desire and Domestic Fiction: A Political History of the Novel, Oxford University Press, 1990

[4] Pretty Woman plot, from Wikipedia

_____________________________

Addendum:

I’m suspicious of scholarly works which “find” romantic love all over the world and in all periods. After reading many such essays I’ve come to the conclusion they confine themselves to biological universals such as the desire for sex, the need for attachment, limerence, social interaction and so on and so forth — all of which falls short of the complex European-derived phenomenon known as courtly & romantic love.

Those academic descriptions omit the idiosyncratic elements that might cast doubt on their universality thesis – details like male masochism, uniquely stylized feudal relationships from France or Germany, the conceptualization of the Virgin Mary and her purity and how that plays into conceptions of gender and love, along with other complex behaviors and influences which make up the courtly love complex arising in medieval Europe.

When Gaston Paris first coined the phrase ‘Courtly Love’ (1883) he was referring precisely to those idiosyncratic elements that render the phenomenon distinct from the universals many scholars reduce it to.

Gaston Paris’ description of courtly love can be summarized as follows:

“It is illicit, furtive and extra-conjugal; the lover continually fears lest he should, by some misfortune, displease his mistress or cease to be worthy of her; the male lover’s position is one of inferiority; even the hardened warrior trembles in his lady’s presence; she, on her part, makes her suitor acutely aware of his insecurity by deliberately acting in a capricious and haughty manner; love is a source of courage and refinement; the lady’s apparent cruelty serves to test her lover’s valor; finally, love, like chivalry and courtoisie, is an art with its own set of rules.” 1

Thus courtly love as defined by Paris has four distinctive traits;

2. The male lover is inferior and insecure; the beloved is elevated; haughty; even disdainful.

3. The lover must earn the lady’s affection by undergoing tests of prowess, valor and devotion.

4. The love is an art and a science, subject to many rules and regulations — like courtesy in general.

It’s clear that what we call romantic love today continues each of these conventions with the sole exception of illegitimacy and furtiveness. With this one exception romantic love can be regarded as coextensive with the courtly love described by Paris.

Many scholars researching this area conveniently overlook (or refuse to mention) the sexual feudalism inherent to the European-descended model of romantic love. Attempts to homogenise and cast romantic love as a global universal, while avoiding all mention of the unsavory sexual feudalism that might render it more problematic and complex, is unhelpful to say the least, and misleading at worst. European-descended romantic love, now the dominant version globally, deserves to be considered separately and need not be confused with more simple theoretical constructs on offer.

Note: [1] Roger Boase, The Origin and Meaning of Courtly Love: A Critical Study of European Scholarship, p.24, Manchester University Press, 1977

What Is Feminism?

There are countless definitions of what ‘feminism’ is, with feminists themselves pointing to glib dictionary definitions, and antifeminists preferring to define it as a female supremacy movement. A hundred other definitions could easily be offered, but the more important question is what (if anything) do all these different definitions hold in common?

Adam Kostakis answers this question in the affirmative below with an elegant definition that most would agree with. – PW

_____________________

FEMINISM

By Adam Kostakis

Even essentially contested concepts, as W. B. Gallie referred to them, must have meanings which are greater than normative, else communication about them would be rendered impossible. That is – there must be some amount of general consensus over what feminism is, between feminists and anti-feminists, or we would not be able to argue about it! Even despite the differences between a feminist’s view of feminism and of our own, some shared content must exist at some level, or we would be talking about entirely different things. They might be talking about the feminist movement, while I am talking about horse-rearing, although we both refer to our respective subjects as ‘feminism’ – but we wouldn’t have much to say to each other, would we, if this were the case?

So, I shall posit the following as a universally applicable definition of feminism; that is to say, it must fit everyone’s criteria for what feminism is, in spite of the different perspectives that different people hold on its nature. It is a suitably limited definition, since it can encompass only those parts of feminism which all definitions hold in common. So, here it is: feminism is the project for increasing the power of women.

That, then, is what everybody who discusses feminism holds in common regarding the concept, whether they are supportive, skeptical, or nihilistically indifferent. No feminist, I think, would deny that this is, at the very least, the ‘bare bones’ of feminism, even if she would prefer to flesh it out in a lot more detail. But that will not do, for beyond this narrow inference, we disagree with each other. To be as objective as possible, then, we must take only that which everybody agrees upon, and that is our universally applicable definition.

Note that there is no mention of equality. This is because there are a number of feminists who explicitly did not pursue equality, but supremacy. So, equality cannot fit into the universal definition of feminism, since certain feminists themselves – who were very famously, unequivocally feminist – disavowed it. To say that feminism is ‘about equality’, then, would be to place oneself in diametrical opposition to several extremely influential feminists! And why, that would be … misogynistic!

Nor can feminism be said to be the project for increasing the power of women relative to men, since, in this counter-feminist’s view, feminists are often quite content to increase the power of women in an absolute sense. That is, they endeavor to grab all they can for women, without reference to the status of men. The phrase ‘relative to men,’ then, only serves to imply that women are power-less relative to men at present, thus casting feminism in an unfairly favorable light. In reality, once women do achieve power which is at an equal or equivalent level to that of men, the demands of feminists do not stop. What we find is that female power becomes entrenched, and extended, and when it surpasses male power, this is simply referred to as ‘parity’ and ignored by feminists – at least, when they are not gloating over men’s newfound powerlessness.

Nor are we able to list, in our universal definition, the specific areas of life, or spheres, in which the feminist project applies. This is because feminism is inherently universalizing; it seeks to colonize and dominate every single facet of life where men and women meet. It aims for domination in every sphere of life, actual and potential.

You may disagree with some of the points above, particularly if you are supportive of feminism. But this does nothing to change our universal definition, because all we can say about those points is that they are contentious. That is, feminists and non-feminists, who are educated about feminism, disagree about these aspects of feminism, and it would simply be biased to take one or the other view for granted. That would be like consulting only Jacobins on the historical accomplishments of the Jacobin Club, or like canvassing only conservatives to explain modern liberalism. It would be a good example of poor methodology, and would help us very little in our search for truth. Right? So then, our universally applicable definition cannot be expanded beyond that which we stated before: feminism is the project for increasing the power of women.

Source: The above excerpt is from Adam Kostakis’ essay Pig Latin.