When Marxist activist Rudi Dutschke looked at ways to stage a neo-Marxist revolution he hit on the plan of “a long march through the institutions of power to create radical change from within government and society by becoming an integral part of the machinery.” His strategy was to work against the established institutions while working surreptitiously within them. Evidence of the attempt to implement his plan can be seen today through many levels of society – especially in universities.

Marxists however are not the only ones to use this strategy. In fact when we look at the numerous political forces attempting to infiltrate and influence our cultural institutions we see that another, much more influential candidate, has twisted its tendrils through every layer of society – and it existed long before Marx and Marxism were born. That force is political feminism,1 whose culture project has been in play now for several hundred years.

Protofeminists like Lucrezia Marinella, Mary Wollstoncraft, Margaret Cavendish, Modesta Pozzo, or Christine de Pizan were advocating a ‘long march’ through institutions for centuries before Marxism emerged and began its tragic experiment. Pizan’s main book for example titled A City of Ladies sketched an imaginary city whose institutions were controlled completely by women, and each of the protofeminists advanced some theory of female rule or ‘integration’ of women into governing institutions. Later feminists followed suit, such as Charlotte Perkins Gillman wrote the famed book HerLand (1915) envisioning a society run entirely by women who reproduce by parthenogenesis (asexual reproduction), resulting in an ideal (utopic) social order free from war, conflict, and male domination.

A survey of protofeminist writings reveals consistent advocacy for the superior abilities of women as functionaries: women’s greater compassion, virtue, nonviolence, intelligence, patience, superior morality and so on, combined with a concomitant descriptions of male destructiveness, insensitivity and inferiority as we see continued in the rhetoric of modern feminists.

Via that polarizing narrative feminists sought to grab not just a big slice of the governance pie; as contemporary feminists have shown they would stop at nothing but the whole pie. Nothing but complete dominance of the gendered landscape would satisfy their lust for control, and it appears they have succeeded.

We see that dominance in women’s occupation of pivotal bureaucratic positions throughout the world, from the UN and World Bank all the way down through national governments, schools and universities, and HR departments in most medium to large workplaces. Feminists not only govern the world via these roles, but as surveyed in Janet Halley’s recent book Governance Feminism: An Introduction, that governance is far from the utopia early feminist promised.

The long feminist tradition underlines the danger of viewing ‘the march through the institutions’ as a Cultural Marxism project, because it deflects us from the historically longer, more powerful, more dangerous and ultimately more successful project that is political feminism.

Moreover, the protagonists of Marxist and feminist worldviews are not one and the same; the former aims to dismantle social-class oppression, and the latter gender oppression. While there are some individuals working to amalgamate these two contrary theories into a hybrid of Frankenstein proportions, their basic theoretical aims remain distinct.

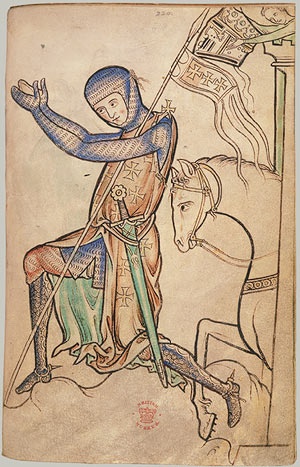

Like Marxism, feminism too can be imagined as a socio-political ideology, in this case modelling itself on a medieval feudalism which was structured with two social classes: 1. A noble class of aristocrats, priests, princes and princesses, and 2. a peasant class of serfs and slaves overseen by indentured vassals.

Stripped of its medieval context we see the purveyors of political feminism working to institute a new sex-stratified version of feudalism which serves to maximize the power of women. With this move we have seen an increased tendency to emphasize women’s “power,” “dignity,” “honor,” “esteem” and “respect” – descriptors historically reserved for dignitaries.

As in medieval times, the assets and wealth generated by the labour class – predominately men – are taxed and redistributed to the new quasi-aristocratic class via a plethora of social spending programs of governments, or alternatively via asset transfers like alimony, child support, divorce settlements and other court mandated conventions. Children themselves form part of that asset portfolio which men are often forced to relinquish to women in the event of divorce. In the face of such practices men are reminded that women’s “dignity” is very much at stake, and their acquiescence mandatory.

The push to establish a female aristocratic class has long been recognized, as mentioned by the following writer from more than a century ago (1896), who in his ‘Letter To The editor’ observed the granting of unequal social privileges to female prisoners;

“A paragraph in your issue of the week before last stated that oakum-picking as a prison task had been abolished for women and the amusement of dressing dolls substituted. This is an interesting illustration of the way we are going at present, and gives cause to some reflection as to the rate at which a sex aristocracy is being established in our midst. While the inhumanity of our English prison system, in so far as it affects men, stands out as a disgrace to the age in the eyes of all Europe, houses of correction for female convicts are being converted into agreeable boudoirs and pleasant lounges…

I am personally in favour of the abolition of corporal punishment, as I am of existing prison inhumanities, for both sexes, but the snivelling sentiment which exempts females on the ground of sex from every disagreeable consequence of their actions, only strengthens on the one side every abuse which it touches on the other. Yet we are continuously having the din of the “women’s rights” agitation in our ears. I think it is time we gave a little attention to men’s rights, and equality between the sexes from the male point of view.–YoursYours, &c.,, A MANLY PROTESTOR,”2

Another comes from a 1910 Kalgoorlie Miner which reported a push to set up a female aristocracy in America. It was entitled The New Aristocracy:

A question of deep human interest has been raised by The Independent.

“To be successful in the cultivation of culture a country must have a leisure class,” says the editor. “We Americans recognise this fact, but we are going about the getting of this leisure class in a new way.

“In Europe the aristocracy is largely relieved from drudgery in order that they may cultivate the graces of life. In America the attempt is being made to relieve the women of all classes from drudgery, and we are glad to see that some of them at least are making good use of the leisure thus afforded them. It is a project involving unprecedented daring and self-sacrifice on the part of American men, this making an aristocracy of half the race. That it is possible yet remains to be proved. Whether it is desirable depends upon whether this new feminine aristocracy avoids the faults of the aristocracy of the Old World, such as frivolousness and snobbishness.”3

Lastly a comment from Adam Kostakis who gives an eloquent summary of feminism’s preference for a neo-feudal society in his Gynocentrism Theory Lectures:

“It would not be inappropriate to call such a system sexual feudalism, and every time I read a feminist article, this is the impression that I get: that they aim to construct a new aristocracy, comprised only of women, while men stand at the gate, till in the fields, fight in their armies, and grovel at their feet for starvation wages. All feminist innovation and legislation creates new rights for women and new duties for men; thus it tends towards the creation of a male underclass.”4

By many accounts what we’ve achieved today under feminist modelling is the establishment of a neo-feudal society with women representing an aristocratic class and men the labour class of serfs, slaves and peasants who too often spend their lives looking up from the proverbial glass cellar. When men do rule, it is usually not with a life “free of drudgery” as mentioned above, but with hard-work as CEOs, executives and prime ministers in service of the ruling female class who are busy with little more than lifting their lattes.

This gendered enterprise is now several hundred years in the making, enjoying further consolidations with every passing year of feminist governance. That a widespread female aristocracy now exists is undeniable, at least in the Western world, although we remain reluctant to name it as such for fear of offending our moral betters. We can only hope that the recent petition to abolish the House of Lords becomes infectious and begins to tackle the unearned privileges of those new aristocrats who serve nobody but themselves.

Sources:

[1]. Ernest Belfort Bax coined the phrase ‘political feminism’ in his book The Fraud of Feminism. London: Grant Richards Ltd, 1913

[2]. A Privileged and Pampered Sex, Letter to the Editor, Reynolds Newspaper, 1896

[3] New Feminine Aristocracy; Narrowly Trained Men, Kalgoorlie Miner, Wednesday 5 January 1910, page 2 (3)

[4]. Adam Kostakis, Lecture 11: The Eventual Outcome of Feminism –II, Gynocentrism Theory Lectures, 2011

*An earlier version of the above article was published in my book Feminism And The Creation of a Female Aristocracy.