“Female Power, Influences, and Privileges” is Chapter-one from ‘Woman: As She Is, And As She Should Be,’ by Elizabeth Poole Sandford. It was published 1835 by Cochrane & Co., and is reprinted here in searchable text form for the first time. This book, written after the death of Mary Wollstonecraft and before the famed Seneca Falls Convention, is already questioning the idea of women as oppressed and lacking in power.- PW.

O ye men; it is not the great king, nor the multitude of men, neither is it wine that excelleth: who is it then that ruleth them, or hath the lordship over them? – Are they not women? By this also ye must know that women have dominion over you. Do ye not labour, and toil, and give, and bring all to the woman? Yea! many there be that have run out of their wits for women, and become servants for their sakes. Many also have perished, and erred, and sinned, for women. — ESDRAS. “

§ 1.–The supremacy of the weak over the strong is a very remarkable phenomenon, and it is as mischievous as it is remarkable. Whatever nature or law may have denied women, art and secret sway give them all: they are influential to a degree perfectly unguessed, and men are possessed by, not possessors of them.

“Woman was made of the man, and for the man:” this is the language of Scripture. Yet, though “expressly given to man for a comforter, for a companion, not for a counsellor,” Woman has managed to overstep her sphere – she has usurped the dominion of the head, when she should have aimed but at the subjection of the heart; and the hand which ought to be held out to the man, only to sustain and cheer him on his journey, now checks his steps, and points out the way he is to go! From moment to moment his purposes are thwarted and broken in upon by a capricious influence, which he scarcely dares to question, yet makes it his pride to indulge. Of this mighty evil it is that we are desirous to give a plain and unbiased view.

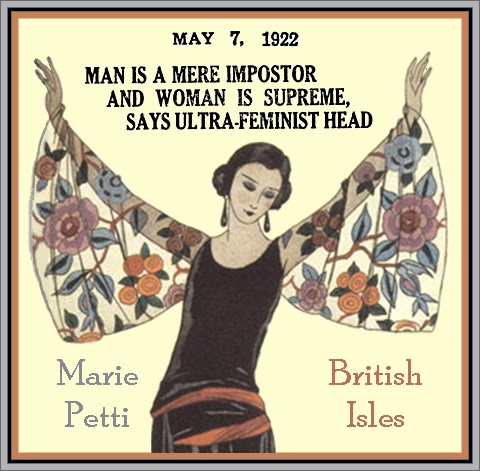

There is, perhaps, no country on earth where women enjoy such, and so great privileges, as in our own. The phenomenon has never passed unobserved by foreigners; and smartly enough it has been said, that were a bridge thrown across our Channel, the whole sex would be seen running to the British shores. In many countries women are slaves; in some they hold the rank of mistresses; in others they are (what they should be everywhere) companions; but in England they are queens!

It was remarked by Steele, even in his time, that “by the gallantry of our nation, the women were the most powerful part of our people;” and assuredly, female influence, far from finding its becoming level, has been on the growth among us ever since. It is now in its “high and palmy state,” and the star of Woman was perhaps never more in the ascendant than at this present writing.1 “The influence of Englishwomen,” as a contemporary observes, “of attractive women” (and a large portion of our countrywomen are attractive) “is vast indeed: be they slaves or companions, sensual toys or reasoning friends, that influence is all but boundless.”

§ 2.–Female influence necessarily exists by sufferance: it can only be by man’s verdict that it exists at all. And herein is the unaccountable part of the whole matter: there is actually something “stronger than strength,” —

And mighty hearts are held in slender chains.”

In the moral philosophy of Paley, there is a remark, so profoundly true, bearing upon our subject, that we cannot consent to hide it in a note. “Could we regard mankind,” says that writer, “with the same sort of observation with which we read the natural history, or remark the manners of any other animal, there is nothing in the human character which would more surprise us, than the almost-universal subjugation of strength to weakness. Among men (in the complete use and exercise of their personal faculties) you see the ninety-and-nine toiling and scraping together a heap of superfluities for one, and this one, too, oftentimes the feeblest and worst of the whole set–a child, a Woman, a madman, or a fool.”

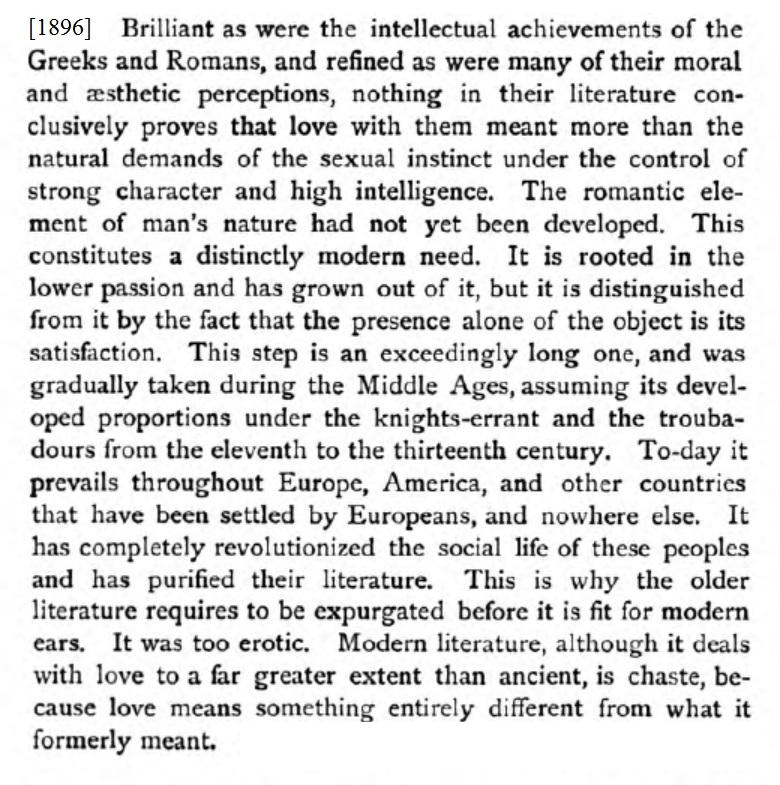

And thus does Man (too often a creature of passion, but never so much or completely so, as when Woman is its object) yield himself an unthinking victim: a most willing bond-slave here, he suffers his head to become the dupe of his passions. How (perhaps many a man asks himself) should he look for harm, where he has garnered up his heart, and where his earliest, latest wishes centre? And yet we may love, like Othello, “not wisely, but too well;” we make unto ourselves idols of the heart, that shall wean us (as they weaned the wisest of old) from sobriety and duty. If the enthusiasm of devotion has sometimes stooped to borrow the language of love, far more often has the madness of love dared to borrow the language of devotion. Like the father in Parnell, our affections may become criminal, and “erring fondness” of this kind, amiable though it be, has to abide its consequences. Providence never fails to avenge any trespass on its own designs.

Led away “by a captive face,” “disturbed by a smile, or undone by a kiss;” a look sufficing to persuade, and a sigh to convince him: this is man’s position!

All they shall need, is to protest and swear,

Breathe a soft sigh, and drop a tender tear.” – Pope

Beauty has but to lecture through her tears, and with Dido of old, “ire iterim in lacrymas, iterum tentare precando,” and resolution is no longer a manly virtue. We resist, and resist, and resist again, –but at length turn suddenly round, and passionately embrace the enchantress.

Few are to be found who do not assume themselves with a toy of some kind during every stage of life, and Woman (though perhaps as little enduring in outward charm as any other, and one that, if critically eyed, would not retain its divinity long), is the most common and most fondled toy of all. How many, calling themselves men, are fooled by those who ought to be their comforters–prayed upon by harpies in the form of angels! The hypocrite affects attachment; the coquette trifles with feeling; the prude strikes at judgment; while the less principled reprobate lays out her traps for heedless passion.

In their most trifling pursuits do women somehow manage to create an almost-universal interest; in all their ordinary doings, in their ‘whereabouts,’–“leurs brouilleries leurs indiscretions, leurs repugnances, leurs penchans, leurs jalousies, leurs piques;” — They have, in fine, continues the author Montesquieu we are quoting, “cet art qu’on les petites ames d’interesser les grandes.” Nor are those mere “women’s fools” –the refuse of the other sex–who are led away blindfold thus: many of its chiefest ornaments are among their “following.” The great and small seem equally content to shape their desires to female foolishness, and with one false tear a pretty woman can undo at a moment what the best and wisest of men have been labouring for years to establish.

What is it Woman cannot do?

She’ll make a statesman quite forget his cunning,

And trust his dearest secrets to her breast,

Where fops have daily entrance.”

Where (apart from outward attractions) this especial fascination which belongs to woman lies, it is difficult to determine; wearing, as it does, the garb of secret and speculative influence, it becomes too vague to submit to a definition–and thus bases itself on a foundation as difficult to examine as to shake. We cannot look into the heart; and where women are concerned, the heart is more especially an enigma.

Thus much, however, may safely be concluded: were women really strong, the contact or the occasional superiority might alarm pride; but, as the truth is, this “mortal omnipotence” is at last but an insect in the breeze; and though a creature which by its will, its wit, or its caprices, is sometimes able to shake us, soul and body, it nevertheless, from instant to instant, is dependent upon ourselves for the minutest succour.

§ 3.–Let us consider female influence under the several aspects in which it presents itself;– and first, as acting upon society at large. The supremacy of women is quite as much general and public, as it is domestic and individual: it spreads along the innumerable lines of social intercourse,–exerting itself, not merely over manners, but, which is often to be regretted, over modes of thinking. We see around the sex an almost-Chinese prostration–of mind as well as body: their approval it is that stamps social reputation–their favour, and their favour alone, that is supposed to confer happiness. Nothing, forsooth, is right, but that which bears their approbation; and theirs alone is the great catholic creed of manners, any deviation from which is heresy. And women have no merit or qualifications then such as they themselves please to dictate,–having been early taught to feel their own consequence, more than what is due to their creature, Man.

§ 4.–But in the connubial state do women exercise the most unlimited power. Female influence, in its action merely over manners and conventionalisms, might seem somewhat on the surface; but such is by no means its narrow bounds: mediately, if not directly, it is an agent in every possible direction. The wife controls her husband, and he acts upon others, and upon the state at large, according to his sphere in life.

Within the whole circle of deception, there is perhaps no creature so completely beguiled as manya modern husband;–we can all, in our private circles, point to a score of instances. Such a being is but an appendage to another–nothing of himself; he is a slave, and a slave of the worst kind–fooled by the bent of another’s will. Free agency is a thing quite gone from him, and, if mere confinement makes not captivity, he suffers a loss of liberty at his own hearth. He is under a charm–loving, as Shakespeare phrases it, with an “enraged affection.” Let the dear enchantress cry for the moon, she should have it from its sphere, were it possible. He would have the world from its axis, to give it her: no one can be richer than she in his promises: she, who but she, the cream of all his care!

Dilige, et dic quicquid voles.”

Women there are affectionate enough–it may be, devoted–in their character as wives; but then, it is at their husbands’ peril to be happy by other means than such as in their wisdom they please to subscribe. Regents of the heart, they take care to govern it most absolutely: and thus it happens (as Phaedrus said long ago) that “men are sure to be losers by the women, as well when they are objects of their love, as when they lie under their displeasure!”

In right of marriage, Englishwomen become endowed with many and great privileges,–privileges that are growing in number and importance every day. Claims, greater than were ever before awarded, are now allowed them in Law and in Equity: over pecuniary matters they have no small control, and are always at full liberty to plunge into wanton expenditure, leaving their husbands the responsible parties.

In short, the ceremony of wedlock, with its present obligations, more than restores any natural inequality between the sexes. No longer are women cyphers beyond the sphere of domestic life: they are parceners of of our power. They are not, it is true, suffered as yet to dispute the prizes of ambition, but they partake largely of its reward; they have the lion’s share–they divide, where they do not monopolise the spoil!

Were it not for difference of dress and person, one might almost mistake the wife for the husband in this country. Her will is not carried in His pocket, as is wisely arranged elsewhere:– “he pays the bills indeed, but my lady gives the treat.” And while she is spending money with both hands, and with a zeal that would lighten the bags of a loan-monger, he has to sell his woods and lands, borrow, or beg!

Slyly and unperceived does the foot of female authority slip itself in: the wedge is easily driven home. This is a species of power that never exists long without favouring itself;–let an ascendancy be once gained (and the collar of command is soon slipped!)–let a system of unsinuation once transfer the authority of wedlock,–and, afterwards, every act, be it of large or small import–what must be done, what is to be said,–becomes not the act of the Man, but of the Woman. It is not planned, it is determined; and where the lady cannot give her reason, she gives her resolution.

Hoc volo, sic jubeo; sit pro ratione voluntas:

Imperat ergo viro!”

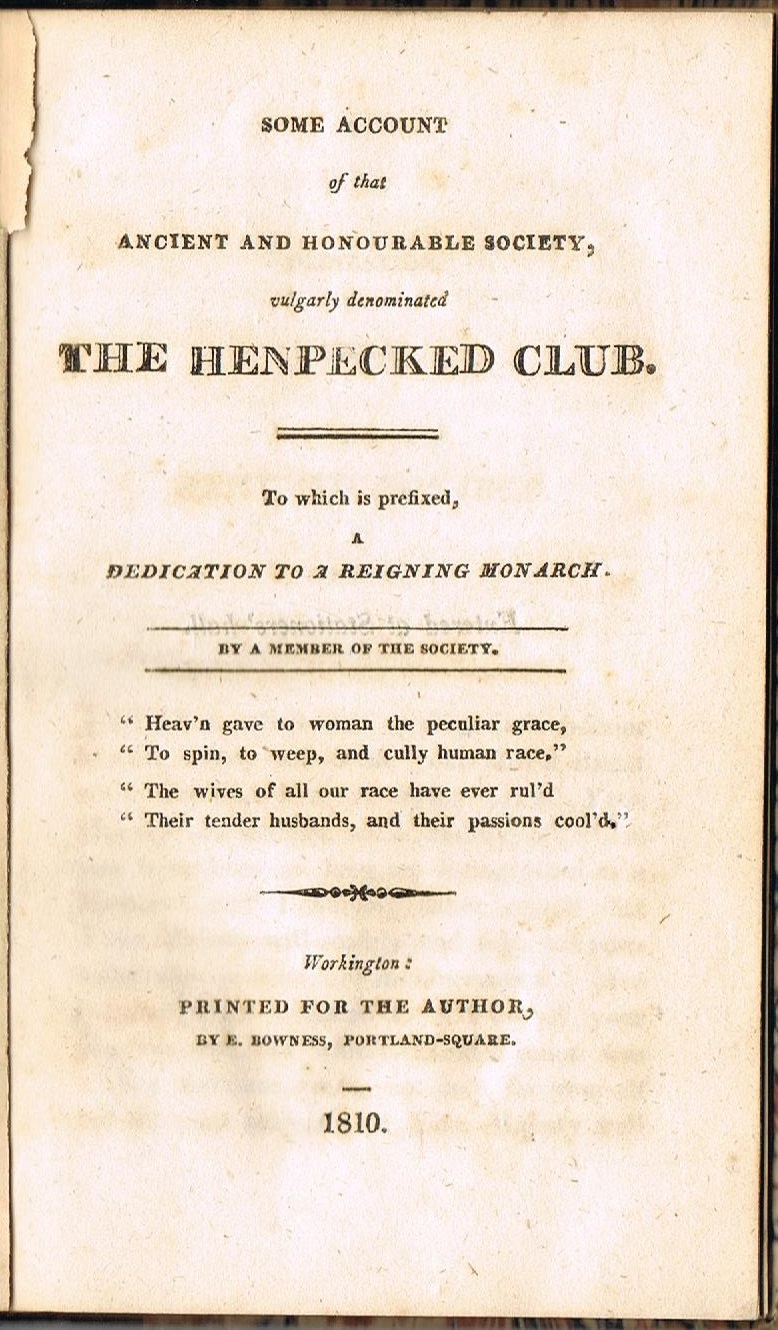

This is “Gynocracy” with a vengeance! as Lord Byron was pleased, on some occasion, to denominate petticoat-sway. This very peculiar and distinct species of government (partaking in its nature not so much of mild despotism, as of a pure unmixed tyranny) has now grown so common among us, that (albeit laid down neither in Plato nor Aristotle) it well deserves, as it has obtained, a definite and scientific denomination.

We have all seen the ivy twining around the oak, but behold a novelty–the oak twining itself about the ivy! The man who suffers himself to be led away blindfold thus, can only be likened to the fool “that rejoiceth when he goeth to the correction of the stocks.”–“Give not thy soul to a woman, to set her foot upon thy substance.” To submit thus is contrary to the first law of nature–it is a direct spurning of Revelation:-

Was she thy God, that thou didst obey?

Or was she made they guide,

Superior, or but equal–that to her

Thou didst resign thy manhood?” — MILTON, P.L.

Let us presume to offer one word of advice to the sex that, in truth, most needs it. Men should let their love be at least manly; it is always possible to be affectionate without being over-fond;–to copy the gentleness, without the amorousness, of the dove. It is in itself a folly to allow those we love to perceive the vehemence of our affection; for such is human nature,–and such especially is female nature, that where it can control, it is nearly sure to become indifferent about pleasing, and at last despotic. Persecution may appear in many shapes, at home as well as abroad; it may address us in the voice of mildness as well as of imperious command; and the soft and playful creatures of our idle hours may cause us misery for years: Nothing is to be disregarded, however seemingly powerless! Though the capacities of Woman are comprised within a narrow sphere, these act within the circle of vigour and uniformity. It is often by seeming to despise power, that women secure it to satiety! A love of power would seem almost part and parcel of Woman’s composition;–for to this end they early learn to enlist every art they are mistresses of;–

In men we various ruling passions find.

In women two almost divide the kind;

These only fix’d, they first or last obey–

The love of pleasure, and the love of sway. — POPE

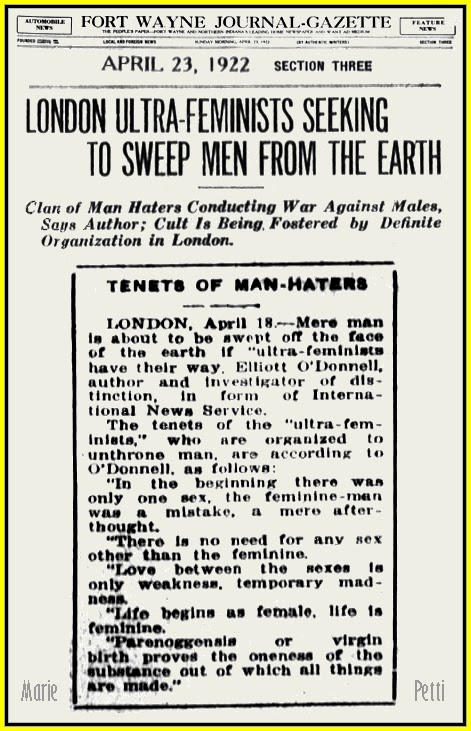

§ 5.–Nor is the political influence belonging to women of contemptible amount. There is an old and true maxim, that though kings may reign, women virtually govern: ’tis they who hold the strings of all intrigues, great or small. “There are perhaps few instances,” says an elegant writer, “in which the sex is not one o the secret springs that regulate the most important movements of private or public transactions.”

Not merely over the fanciful regions of fashion does the female empire extend itself; it dictates to the senate, as well as legislates for the ball-room. Women make no laws, it is true; they abrogate none: in so far Law shakes hands with Divinity; but they have an influence beyond any law: “Ce que femme veut, Dieu le veut?” Nothing resists them! What follows, though it be poetry, is too true a picture.

What trivial influences hold dominion

O’er wise men’s counsels and the fate of empire!

The greatest schemes that human wit can forge,

Or bold ambition dares to put into practice,

Depend upon our husbanding a moment,

And the light lasting of a Woman’s will!” — ROWE

Nor are women without civil and political power of the direct kind. They are vested with many important trusts, and enjoy most of those privileges which accompany property. They vote for many public functionaries, and their sweet voices are made admissible in electing directors for the government for thirty or forty millions of souls of British India.

And where their influence is but indirect, it is little less powerful on that account. In our public elections ’tis they who are the actual constituency,–they, after all, who virtually elect; for which is the vote that they do not influence? The system of female canvassing has of late years become a traffic quite notorious.

The lady in Hudibras, did not exceed the truth when she asserted the vast powers and privileges of her sex:–

We manage things of greatest weight

In all the world’s affairs of state;

We make and execute all laws

can judge the judges and the cause;

We rule in every public meeting

And make men do what we judge fitting;

We are magistrates in all great towns

Where men do nothing but wear gowns!

We are your guardians, that increase,

Or waste, your fortunes as we please;

And, as you humour us, can deal

In all your matters, ill or well.”

Notes:

[1] “A low estimate of female pretensions is certainly not the fault of the present day. Women are, perhaps, sometimes in danger of being spoilt, but they cannot complain that they are too little valued. Their powers are too highly rated: their natural defects are overlooked, and the consideration in which they are held, the influence they possess, and the confidence placed in their judgment, are in some instances disproportionate with their real claims.” — Mrs. Sandford