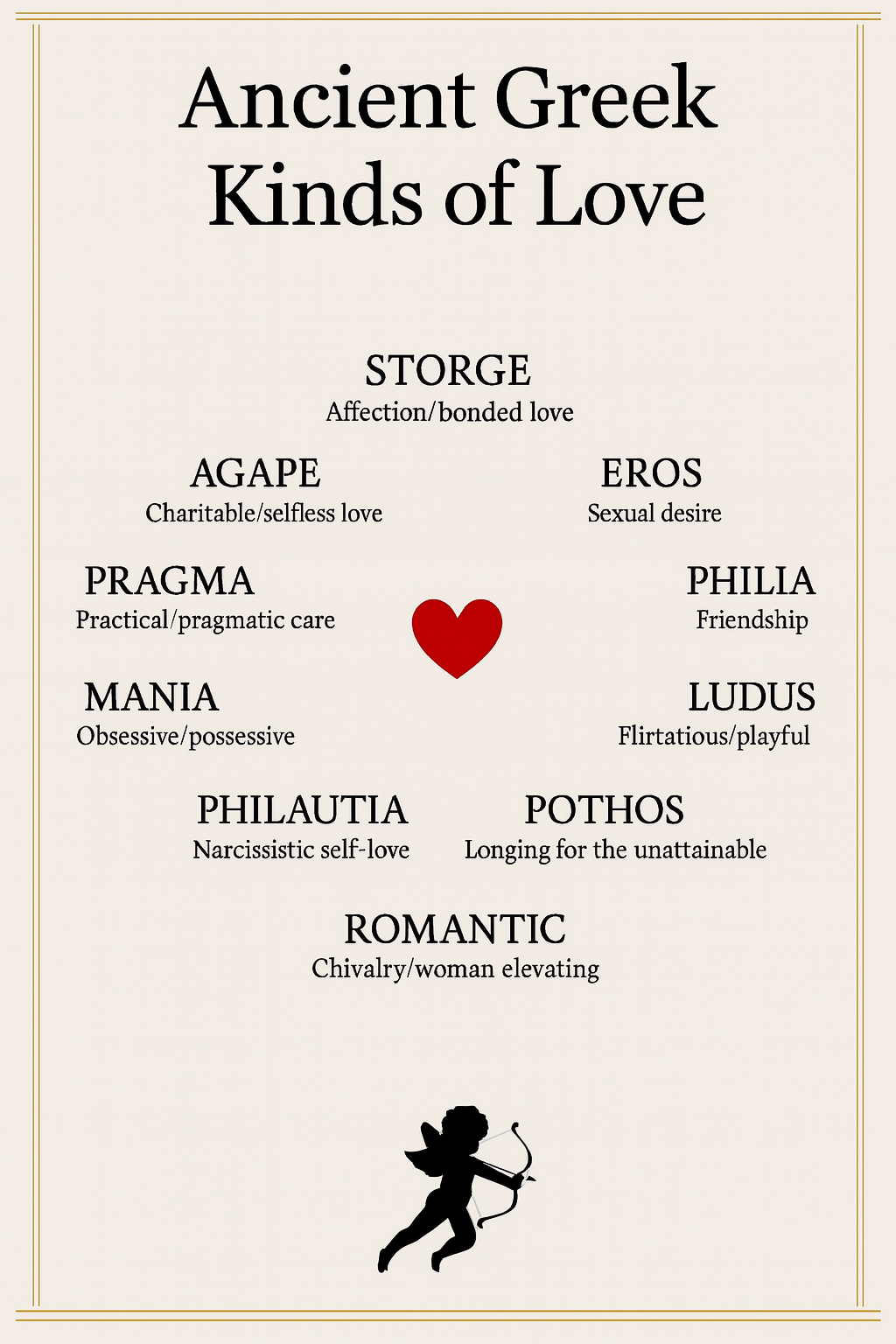

We’ve all heard that love is divine, but do we know which god has sent the love letter, and what kind of love is intended….. eros? agape? romance?

romantic love

Count Leo Tolstoy criticizes romantic love

* * *

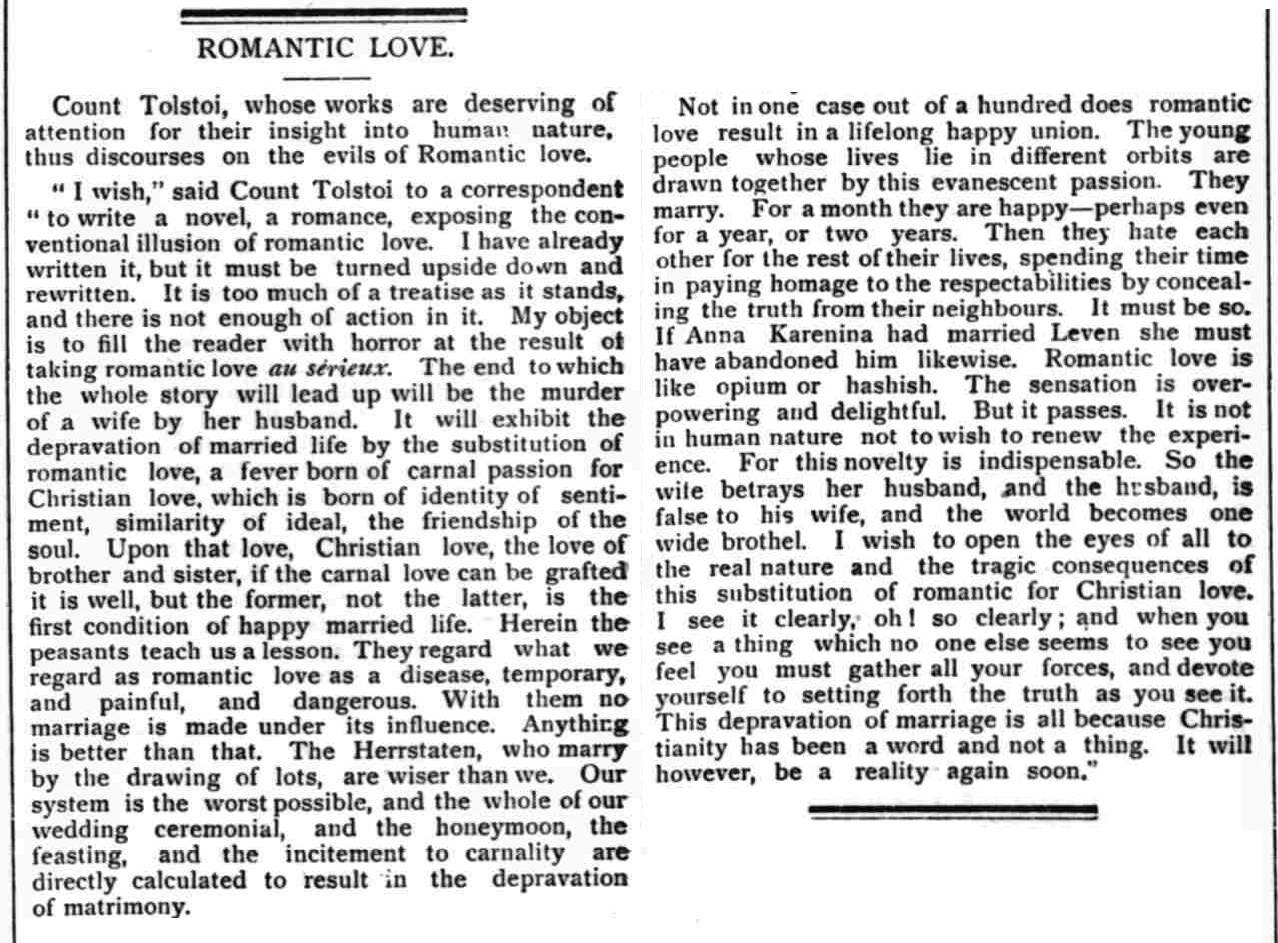

ROMANTIC LOVE

Count Tolstoi, whose works are deserving of attention for their insight into human nature, thus discourses on the evils of Romantic love.

“I wish,” said Count Tolstoi to a correspondent “to write a novel, a romance, exposing the conventional illusion of romantic love. I have already written it, but it must be turned upside down and rewritten. It is too much of a treatise as it stands, and there is not enough of action in it.

My object is to fill the reader with horror at the result of taking romantic love au sérieux. The end to which the whole story will lead up will be the murder of a wife by her husband. It will exhibit the depravation of married life by the substitution of romantic love, a fever born of carnal passion for Christian love, which is born of identity of sentiment, similarity of ideal, of friendship of the soul. Upon that love, Christian love, the love of brother and sister, if the carnal love can be grafted it is well, but the former, not the latter, is the first condition of happy married life.

Herein the peasants teach us a lesson. They regard what we regard as romantic love as a disease, temporary and painful, and dangerous. With them no marriage is made under its influence. Anything is better than that. The Herrstatten, who marry by the drawing of lots, are wiser than we. Our system is the worst possible, and the whole of our building ceremonial, and the honeymoon, the fasting, and the incitement to carnality are directly calculated to result in the depravation of matrimony.

Not in one case out of a hundred does romantic love result in a lifelong happy union. The young people whose lives lie in different orbits are drawn together by this evanescent passion. They marry. For a month they are happy—perhaps even for a year, or two years. Then they hate each other for the rest of their lives, spending their time in paying homage to the respectabilities by concealing the truth from their neighbours. It must be so.

If Anna Karenina had married Leven she must have abandoned him likewise. Romantic love is like opium or hashish. But it passes. It is not overpowering and delightful. But it passes. It is not human nature to wish to renew the experience. For this novelty is indispensable. So the wife betrays her husband, and the husband, is false to his wife, and the world becomes one wide brothel.

I wish to open the eyes of all to the real nature and the tragic consequences of this substitution of romantic for Christian love. I see it clearly; oh! so clearly; and when you which no one else seems to see a thing which no one else forms and you see a thing which no one else forms and you feel you must gather all your forces, and devote yourself to setting forth the truth as you see it. This depravation of marriage is all because Christianity has been a word and not a thing. It will however, be a reality again soon.”

[Source: Civil & Military Gazette (Lahore) – Friday 21 December 1888]

J.R.R. Tolkien criticizes chivalry and courtly love

1. On the Artificiality and False Deification of Love and the Lady:

“There is in our Western culture the romantic chivalric tradition still strong, though as a product of Christendom (yet by no means the same as Christian ethics) the times are inimical to it. It idealizes ‘love’ — and as far as it goes can be very good, since it takes in far more than physical pleasure, and enjoins if not purity, at least fidelity, and so self-denial, ‘service’, courtesy, honour, and courage. Its weakness is, of course, that it began as an artificial courtly game, a way of enjoying love for its own sake without reference to (and indeed contrary to) matrimony. Its centre was not God, but imaginary Deities, Love and the Lady. It still tends to make the Lady a kind of guiding star or divinity – of the old-fashioned ‘his divinity’ = the woman he loves – the object or reason of noble conduct. This is, of course, false and at best make-believe. The woman is another fallen human-being with a soul in peril.” (Letter #43 – The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, 2000)

2. On the Unrealistic and Permanent Notion of Romantic Love:

“It is not wholly true, and it is not perfectly ‘theocentric’. It takes, or at any rate has in the past taken, the young man’s eyes off women as they are, as companions in shipwreck not guiding stars. (One result is for observation of the actual to make the young man turn cynical.) To forget their desires, needs and temptations. It inculcates exaggerated notions of ‘true love’, as a fire from without, a permanent exaltation, unrelated to age, childbearing, and plain life, and unrelated to will and purpose. (One result of that is to make young folk look for a ‘love’ that will keep them always nice and warm in a cold world, without any effort of theirs; and the incurably romantic go on looking even in the squalor of the divorce courts).” (Letter #43 – The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, 2000)

ANALYSIS:

In these passages, Tolkien critiques the chivalric tradition of courtly love on several grounds:

Artificial Origins: He describes courtly love as an “artificial courtly game” designed to enjoy love outside the context of marriage, which he sees as contrary to moral and spiritual ideals.

False Idolatry: Tolkien argues that the tradition elevates “Love” and “the Lady” to the status of “imaginary Deities,” displacing God as the true center of devotion. This deification of the beloved woman is “false and at best make-believe.”

Unrealistic Expectations: He criticizes the romantic notion that love is a “permanent thing” requiring no effort, which sets unrealistic expectations and contributes to marital breakdowns when challenges arise.

Distraction from Reality: Tolkien warns that idealizing women as “guiding stars” or divinities prevents men from seeing them as “fallen human-being[s]” and equal partners in life’s struggles, leading to a distorted view of relationships.

* * * *

Source:

These excerpts are drawn from The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, edited by Humphrey Carpenter (Houghton Mifflin, 2000, ISBN: 978-0618056996). Due to copyright, only the relevant excerpts are quoted from Letter 43 of the 2000 edition.

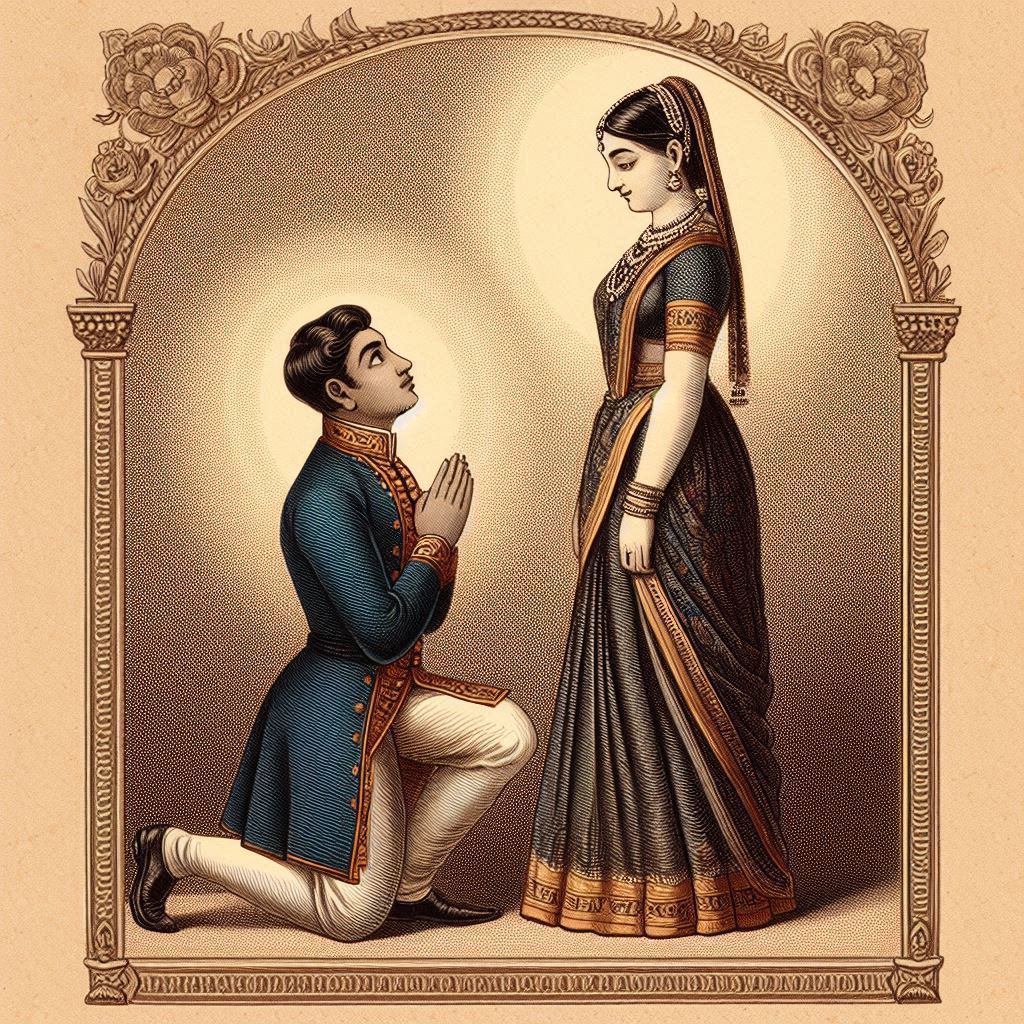

When European Gynocentrism Came To India

During British colonial rule in India, the Western customs of romantic love and chivalry began to influence Indian society, particularly among the upper classes, as they sought to project an image of “civilization.” This was the beginning of traditional gynocentrism.

The Indian image of the ‘devi’ (divine woman) was constructed during the British colonial period. By borrowing elements from traditional Hindu Brahmanical, patriarchal values and those of Victorian England, the Indian men made an effort to project themselves as ‘civilized’ in response to the colonial imagery brought into India. The ideas of ettiquette, chivalry, and romantic love were implanted onto existing patriarchal joint family norms. 1

During the period of the Raj, Anglo-Indian romance novels written by British women, and these love stories were symptomatic of British fantasies of colonial India and served as a forum to explore interracial relations as well as experimenting with the modern femininity of the New Woman witthin Indian culture.2 These Anglo-Indian romance novels often explored interracial relationships, with racial differences serving as a structural framework for the romantic narrative. 2

The idea of romantic love, shaped by British Romanticism and chivalric notions, influenced literature, culture, and societal norms in colonial India. Below are some scholarly works and key references that address this topic:

1. “The Romantic Imagination in Colonial India” by Homi K. Bhabha

- Summary: Bhabha examines how colonial subjects in India were influenced by European Romanticism, which included ideals of individualism and emotional expression in love. The British colonialists, through their literature and cultural practices, promoted a concept of love that was distinct from traditional Indian ideals.

- Citation: Bhabha, H. K. (1994). The Location of Culture. Routledge.

2. “The British Empire and the Culture of Romance” by James D. Laidlaw

- Summary: This book explores how the British Empire, including its administration and literature, promoted the ideals of chivalric love, heroic virtue, and emotional expression, which were later incorporated into Indian culture. It discusses how British officers and administrators saw themselves as part of a chivalric mission in their dealings with India.

- Citation: Laidlaw, J. D. (2002). Romanticism and Colonialism: An Historical Study. Cambridge University Press.

3. “Love, Romanticism, and Imperialism: A Cross-Cultural Analysis of British and Indian Love Narratives” by Gauri Maulik

- Summary: Maulik delves into the cross-cultural exchange between Britain and India, focusing on how British romantic narratives influenced the portrayal of love in Indian literature. Romanticism, as shaped by British literature, was absorbed and adapted in the Indian context, often blending with traditional Indian ideals of love.

- Citation: Maulik, G. (2010). Love and Empire: Colonial Encounters in Romantic Literature. Oxford University Press.

4. “Colonial Encounters: Gender and the Indian Elite” by Ania Loomba

- Summary: This work focuses on the gender dynamics during the colonial era, including how British ideas of romance and love affected the portrayal of women and relationships in India. British ideas of courtly love, often steeped in chivalric values, were contrasted with the more rigid and socially structured ideas of love in Indian society.

- Citation: Loomba, A. (1998). Colonialism/Postcolonialism. Routledge.

5. “Romanticism, Colonialism, and the Cultural Politics of Love” by Elizabeth Jane Hill

- Summary: This paper examines how the British romantic imagination, with its focus on passionate, often idealized love, affected the cultural landscape in colonial India. It explores how these Western notions of romantic love were adopted by Indian writers, especially in the context of English-educated elites.

- Citation: Hill, E. J. (2015). Romanticism, Colonialism, and the Cultural Politics of Love. Journal of Postcolonial Writing, 51(2), 163-177.

6. “Colonial Modernity in India” by Partha Chatterjee

- Summary: Chatterjee discusses the broader impact of British colonialism on Indian society, including how Western concepts of love and marriage became entangled with traditional Indian customs. The “modern” notion of romantic love was promoted among the English-educated elite, especially in literature and the arts.

- Citation: Chatterjee, P. (1993). The Nation and Its Fragments: Colonial and Postcolonial Histories. Princeton University Press.

7. “The English Language and Indian Literature” by A. K. Ramanujan

- Summary: Ramanujan addresses the introduction of English literature and the English language in India, which included the romantic and chivalric themes of British poetry and novels. Indian authors, especially those from the English-educated classes, were influenced by these new ideas of love and self-expression, as seen in their works.

- Citation: Ramanujan, A. K. (1999). The Collected Essays of A. K. Ramanujan. Oxford University Press.

These sources provide a comprehensive view of how British romantic ideals, especially those connected to chivalry and courtly love, influenced Indian society during the colonial period, particularly through literature, education, and elite cultural practices.

References:

Tolstoy on Romantic Love

Madame Bovary Syndrome (English Translation from the original French paper – 1892)

Madame Bovary Syndrome (bovarysme/bovarism) represents women’s delusional fixation on the ideals of romantic love. The term was coined by French writer J. de Gaultier in his 1892 essay Le bovarysme, la psychologie dans l’oeuvre de Flaubert, with the following two excerpts translated (and paraphrased) from the original French essay. – PW

Mr. Montégut noted that the appearance of Madame Bovary “was a reaction to certain long-sovereign influences.” She stood in all reality for the false ideal made fashionable by the school of romantic love and for the dangerous sentimentality that has as its counterpart the male figure of Don Quixote who was a consequence for the too long-prolonged chivalric mania of Spain.

Mr. Montégut continues; “As Cervantes dealt the death blow to the chivalrous mania with the very weapons of chivalry, it is with the very same processes that G. Flaubert has destroyed the false ideal promoted by the romantic love school; it is with the very resources of the romantic imagination that he has painted the vices and errors of that imagination in the figure of Madame Bovary.” [Page 11]

* * *

If all of Flaubert’s characters reveal in their feelings and in their ideas the morbid principle that governs them, there is one who manifests a more complete, singularly evil set of symptoms: Madame Bovary. Equipped with a strongly accentuated temperament and an active will, she creates within herself, in contradiction to her real nature, a being of imagination, made of the substance of her reveries and enthusiasms.

In complete good faith she incarnates in this ghost, and lends it passions and desires, putting in it all the tension of her nerves, and putting all the energy of her soul at its service to satisfy them. Her true instincts however, always ready to emerge, protest with their violence against this usurpation and try to reconquer the place that has been taken from them; she strives to stifle their calls, and with incredible determination she persists in turning her eyes away from herself, seeing herself only under the appearance of her dream.

Her entire life is torn apart by this poignant struggle between her little-known real self and the chimerical monster she has installed in her brain. Thus torn between these two equal powers, abused by the false romantic ideal that she has formed of herself, the poor woman becomes this hybrid being dedicated to the necessary lie and leading ultimately to suicide, which alone puts an end to her terrible duality.

By the obstinate blindness by which she carried out her incessant evolution, and by her tragic end, she personified in herself this original disease of the human soul for which her name can serve as a label: we can understand that “Bovarysm” is the faculty given to man to conceive of himself otherwise than he is, without taking into account the various motives and external circumstances which determine this intimate transformation in each individual. [Page 26]

SEE ALSO: What is Madame Bovary Syndrome?

Pearl Davis: Romantic Chivalry And The Rise Of Gynocentrism

Challenging The Claim That Romantic Love is Universal: Excerpt from William Reddy’s The Making Of Romantic Love

The following excerpt is from William Reddy’s The Making of Romantic Love, elaborating on the problem of conflating romantic love with more universal forms of love. – PW

* * *

The Anthropology of Romantic Love

The English word love can mean so many different things that, by convention, one adds the word “romantic” to distinguish those types of love that include a sexual component from all other types of love. This is the sense of “romantic love” deployed by William Jankowiak and Edward Fischer in a widely cited study published in 1992.1 The authors presented evidence that romantic love was present in 147 out of 166 cultures, or 88.5 percent. Their definition of romantic love was very broad. Evidence of any one of five criteria was regarded as sufficient: (1) accounts of personal anguish and longing, (2) love songs or folklore “that highlight the motivations behind romantic involvement,” (3) elopements due to mutual affection, (4) native accounts of passionate love, and (5) ethnographers’ affirmations.

The authors believed their findings disproved a view expressed by a number of scholars that romantic love was found only in modern individualistic societies. The evidence, they concluded, strongly supported the universal occurrence of romantic love. Jankowiak subsequently edited an anthology of essays by ethnographers presenting evidence for the existence of romantic love in a variety of cultural settings from West Africa to Polynesia.2

In a 1998 essay, Charles Lindholm rejected Jankowiak and Fischer’s conclusion, however, on the grounds that their definition of romantic love lacked sociological and cultural specificity.3 […] Lindholm’s observations strongly indicate the need for a more nuanced vocabulary. After all, his objection to Jankowiak and Fischer’s conclusions may be the result of a terminological confusion. Jankowiak and Fischer cast the widest possible net that the term “romantic love” permits.

In this study, the term “longing for association” will be used to refer to that wide net that Jankowiak and Fischer cast, and the term “romantic love” will be reserved to refer to those forms of the longing for association that have emerged in Western and Western-influenced cultural settings where one or another of the historical versions of desire-as-appetite is accepted as common sense.

To illustrate the importance of this distinction, consider a case mentioned by Leonard Plotinicov in the 1995 anthology edited by William Jankowiak. Plotinicov reports on a Nigerian informant who became fascinated, even obsessed with his third wife the moment he saw her. Although he already had two wives, he said, “I told her I wanted to marry her. She said she had nothing to say about that, and directed me to her parents.” He immediately went to negotiate with the parents and soon married her.4 Whatever this man’s emotion was, to equate it with “romantic love” as practiced in certain Western settings is to ignore the centrality of reciprocal feeling and of exclusivity in Western norms for love partnerships.

References:

[1]. William R. Jankowiak and Edward F. Fischer, “A Cross-Cultural Perspective on Romantic Love,” Ethnology 31 (1992): 149–55.

[2]. William R. Jankowiak, ed., Romantic Passion: A Universal Experience? (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995).

[3]. Charles Lindholm, “Love and Structure,” Theory, Culture & Society 15 (1998): 243–63.

[4]. Leonard Plotinicov, “Love, Lust and Found in Nigeria,” in Romantic Passion: A Universal Experience? ed. William Jankowiak (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995), 128–40, quote from p. 134.

See also: A Brief Commentary On Jankowiak & Fischer’s Misuse Of The Term Romantic Love

A brief commentary on Jankowiak & Fischer’s misuse of the term ‘romantic love’

The following elaborates on a common misrepresentation of what romantic love is. – PW

* * *

It’s amazing to observe how many academics have adopted a flawed idea of what romantic love is – all because Jankowiak & Fischer1 claimed to both define, and then find evidence of romantic love in 147 out of 166 cultures. However their definition does not match the romantic love construct from Europe which rested squarely on a feudal template of men serving elevated ladies – a template that is missing from Jankowiak & Fischer’s definition. As the most popular kind of love in the world today, this is no small oversight.

Romantic love is, in fact, different from the more generic form of love they describe.

Even the great Steve Stewart-Williams uncritically accepts Jankowiak & Fischer’s romantic love construct which omits the feudal template (ie. man as vassal, woman as lord), an omission that results in their construct not being romantic love at all because it is lacking its most definitive element.

Jankowiak & Fischer defined romantic love as based on intimacy, passion, commitment, idealization, limerence, and so on, and omitted the central relevance of the feudal template. But no feudal metaphor = no romantic love. Academics relying on such misinformation overlook the novelty of romantic love as does Stewart-Williams in his otherwise wonderful book on evolutionary psychology titled ‘The Ape Who Understood The Universe.‘ There he writes:

The question all these findings raise is a straightforward one: If romantic love is an invention of Western culture, why is it found in every geographical region, historical period, and ethnic group? The simplest and most plausible answer is that romantic love is not an invention of Western culture. Instead, the idea that romantic love is an invention of Western culture is itself an invention of Western culture, and a rather implausible one at that. Human beings were falling in and out of love for hundreds of thousands of years before we ever had Hollywood blockbusters or knights in shining armor. We’re just that kind of animal – the kind that falls in love from time to time.

Its clear that some academics are attempting to universalize a medieval phenomenon that is not, in fact, universal. And many subsequent academics are simply quoting, without checking, the robustness of the earlier study by Jankowiak & Fischer. Have they never read pre-medieval European literature, or perhaps Chinese history for alternative descriptions of love?

For example, the following quote is from the book Love and Women in Early Chinese Fiction By Daniel Hsieh (2009),2 which describes an absence of the European template in China:

The idea of a purely romantic hero, a man as both an amorous and exemplar figure, is almost unknown. Most modern readers would react to the Chinese romances with sentiments akin to E. D. Edwards who declared, “Of all characteristics of Chinese fiction which are foreign to European ideas none is more striking than the inadequacy of the hero of love stories. The nominal hero is generally a quite unheroic person….”. Given the norms of the culture this was inevitable. Romance ordinarily had little place in the life of a wenren, and any attempt to raise its position is problematic. A “real” man was not a lover. Earlier we saw an example from the Shishou xinyu where an individual was laughed at for his excessive devotion to his wife. In “Diao Wei Wudi wen”, Lu Ji (261–303) writes, “As for entangling one’s emotions on extraneous objects or setting one’s thoughts on women (gui fang), these are things that a wise and outstanding man had best avoid.” In a Confucian world, feelings for the opposite sex were sublimated. It is not that women were necessarily seen as “evil.” Rather, having little place in moral and philosophical realms, they threatened to hinder a person from higher pursuits. One’s “passion” should be for ruler and state, and very early there evolved the model of the wenren official assuming the role of lover with the ruler being the object of his devotion. Some of the most passionate poetry in the tradition – Qu Yuan’s verse in Chu ci – is based on this idea. As Arthur Waley noted when discussing the “Li sao” (Encountering Sorrow), “In this poem, sex and politics are curiously interwoven, as we need not doubt they were in Chu Yuan’s own mind. He affords a striking example of the way in which abnormal mentality imposes itself.” In the West there occurred an interesting reversal of this notion. The rise of courtly love involved a kind of “feudalisation of love” in which man devoted himself to a lady in the way a vassal devoted himself to his lord.

It’s revealing to contrast the Chinese position that, quote “a real man was not a lover” with the opposite convention coming out of 12th century Europe where, “Here the truest lovers are now the best knights.”3

This error of claiming romantic love as universal is akin to saying all four-legged animals are horses because horses have four legs. This kind of logic is relevant to hippophiles, but it isn’t science……. even if horses do, in fact, have four legs. Same with romantic love – it needs to be differentiated from more generic love constructs and not blurred together.

C.S. Lewis rightly defined courtly & romantic love as “a feudalisation of love.” Again, if there’s no feudal template (eg. is absent in many other cultures’ version of love), there’s no romantic love. So-called research that omits this point is an attempt to universalise a novel social construct. The feudal factor permeates the phenomenon of romantic love, and must be included as a guiding factor in any attempts at a cross-cultural study on romantic love. However, because this factor was omitted by Jankowiak & Fischer it renders their study misleading if we consider that the Europe-derived model has become the dominant format in many cultures today; if we are going to use the exact phrase romantic love it deserves a more detailed description.

The kind of love that Jankowiak & Fischer do end up describing and then sampling in 166 cultures is more accurately phrased as pairbonding love, which does indeed exist in all cultures. To (mis)use the European phrase romantic love leads to confusion; so I would recommend they, and all researchers who have followed them, consider making this terminology change.

The feudal metaphor is symbolised in this image of a man going down on one knee in a pledge of lifelong service to a woman considered elevated. This is a continuation of the commendation ceremony of the Middle Ages.

Addendum: Since writing the above commentary, I have communicated with both Jankowiak and Fischer who inform me that the above terminology problem has been recognized and addressed by them some time ago, leading to the dropping of the phrase romantic love and replacing it with the more suitable designation passionate love in subsequent publications.

References:

[2] Hsieh, D. (2009). Love and women in early Chinese fiction. The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press.

[3] Wollock, J. G. (2011). Rethinking chivalry and courtly love. ABC-CLIO.

FOOTNOTE

The following excerpt from William Reddy’s The Making of Romantic Love, elaborates on the conflation of romantic love with more universal forms of love. – PW

* * *

The English word love can mean so many different things that, by convention, one adds the word “romantic” to distinguish those types of love that include a sexual component from all other types of love. This is the sense of “romantic love” deployed by William Jankowiak and Edward Fischer in a widely cited study published in 1992.1 The authors presented evidence that romantic love was present in 147 out of 166 cultures, or 88.5 percent. Their definition of romantic love was very broad. Evidence of any one of five criteria was regarded as sufficient: (1) accounts of personal anguish and longing, (2) love songs or folklore “that highlight the motivations behind romantic involvement,” (3) elopements due to mutual affection, (4) native accounts of passionate love, and (5) ethnographers’ affirmations. The authors believed their findings disproved a view expressed by a number of scholars that romantic love was found only in modern individualistic societies. The evidence, they concluded, strongly supported the universal occurrence of romantic love. Jankowiak subsequently edited an anthology of essays by ethnographers presenting evidence for the existence of romantic love in a variety of cultural settings from West Africa to Polynesia.2

In a 1998 essay, Charles Lindholm rejected Jankowiak and Fischer’s conclusion, however, on the grounds that their definition of romantic love lacked sociological and cultural specificity.3 […] Lindholm’s observations strongly indicate the need for a more nuanced vocabulary. After all, his objection to Jankowiak and Fischer’s conclusions may be the result of a terminological confusion. Jankowiak and Fischer cast the widest possible net that the term “romantic love” permits.

In this study, the term “longing for association” will be used to refer to that wide net that Jankowiak and Fischer cast, and the term “romantic love” will be reserved to refer to those forms of the longing for association that have emerged in Western and Western-influenced cultural settings where one or another of the historical versions of desire-as-appetite is accepted as common sense.

To illustrate the importance of this distinction, consider a case mentioned by Leonard Plotinicov in the 1995 anthology edited by William Jankowiak. Plotinicov reports on a Nigerian informant who became fascinated, even obsessed with his third wife the moment he saw her. Although he already had two wives, he said, “I told her I wanted to marry her. She said she had nothing to say about that, and directed me to her parents.” He immediately went to negotiate with the parents and soon married her.4 Whatever this man’s emotion was, to equate it with “romantic love” as practiced in certain Western settings is to ignore the centrality of reciprocal feeling and of exclusivity in Western norms for love partnerships.

References:

[1]. William R. Jankowiak and Edward F. Fischer, “A Cross-Cultural Perspective on Romantic Love,” Ethnology 31 (1992): 149–55.

[2]. William R. Jankowiak, ed., Romantic Passion: A Universal Experience? (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995).

[3]. Charles Lindholm, “Love and Structure,” Theory, Culture & Society 15 (1998): 243–63.

[4]. Leonard Plotinicov, “Love, Lust and Found in Nigeria,” in Romantic Passion: A Universal Experience? ed. William Jankowiak (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995), 128–40, quote from p. 134.

See Also:

– Is Romantic Love a Timeless Evolutionary Universal, or a Frankenstein Creation of The Middle Ages?

– A comment on Don Monson’s ‘Why is la Belle Dame sans Merci? Evolutionary Psychology and the Troubadours’

Arranged Marriages and the Rise of Romantic Love

In this video Paul Elam looks at the tradition of arranged marriage, while contrasting it to the false sense of superiority Westerners ascribe to relationships based on ‘romantic love.’