By Vernon Meigs

Man’s dignity begins with and is measured by how he stands his ground. When you see a man who does, you see a man with his spirit intact, defended, or being healed. You are seeing a man who owns himself, and belongs to no one else. This is one kind of man.

Now direct your attention to another kind of man: the man who kneels. The man on his knees. You see a man who lives by others’ expectations, others’ arbitrary standards, and others’ undue authority. You see a man that does not own himself, and his spirit broken.

The question of the purpose of man, in both the senses of humanity and the human male, is of particular urgency in something such as the Men’s Human Rights Movement. The case for men standing his ground today is in tandem to the case that he was always meant to.

We once again address the bizarre case for “natural gynocentrism” which attempts to determine that man is meant to service womankind, intrinsically, because of “biological reasons”. Attached to it is the notion that man should not change it and instead accept such an existence, albeit with the possible stipulation that gynocentrism has “gotten out of hand”.

This is the notion that mankind evolved to pedestalize women, and that’s why we are here. Ergo, man was always meant to live on his knees for women. Because biology.

It is for this reason we must make clear and advocate for a new cultural narrative that says no, mankind was never meant to grovel, but instead is meant to hold himself up, and always was.

Perhaps it is much more than a convenience of evolution that human beings are creatures that stand tall on two legs. It could be that there is a deeper, metaphysical meaning behind that evolution. What does it mean to bring such a creature down from where he stands?

The observant will notice that not only is there not enough defense of the man who stands for himself, but rather glorifies the kowtower, and alleges its charm, calling it “humility.”

If it is improper for a human being to be brought to his knees, then it follows that it is improper that anybody expects another human being to be on their knees for them. Taking all of this into consideration, we can point at where kneeling takes place in our society – who does them, for whom. Who expects this behavior. Who demands it. Who can’t imagine life without it.

From kowtowing to authority figures to going on his knees to attain women’s approval, mankind has made this practice an unquestioned habit. Under comfortable labels such as “sacrifice”, “humility”, “service” and even “love”, the symbolic groveling act holds the status of virtuous behavior. The refusal to do so holds the status of reckless independence, stubbornness, and adolescent rebellion.

They are, in fact, partly right about the latter. Standing tall and defiant on one’s feet requires independence. A streak of recklessness, for lack of a better term, can be a recipe for successful risk-taking endeavors where necessary. There is no problem with stubbornness if it means refusal to compromise one’s values and the well-being of himself and his own kin. Some of us can stand to revisit our adolescent energy in the face of the Saturnian stagnation of cold authority. Furthermore, being a rebel for the right cause is always noteworthy.

Make no mistake that those that uphold the virtues of subservient existence consider these qualities anathema. They aren’t misnomers, meaning that they are not mistaken in their choice of words as they blame independence for not being a good, humble-enough groveler.

What it Means to Kneel

Cast off all the clutter of empty justifications and excuses in the mind that grasps for any wholesome meaning to kneeling, and let’s cut to the chase with this one. I’m going to tell you what going down on your knees really means.

We have to realize that kneeling is not a picture made up of one figure, but at least two. Even if it is a solo act, something abstract fills the second role. Figure A is of course the kneeler, the creature on his knees. Figure B is the one that Figure A is at the feet of. Figure B stands, and looks down at Figure A.

B knows that the dirt is A’s rightful place. B may profess “compassion” and can possibly permit B to look up at A, emphasis on permit, but not generally; typically, A must avert his eyes.

The brutally honest interpretation of the image is Figure A representing the defeated being, the diminished, the lower, the inferior, the unworthy; Figure B would then represent the pedestalized, the exalted, the usurper, the tyrannical, the one that looks down and condescends.

This is a common historical toxic relationship between two humans – one human basking in the glory of being higher of another lowly, broken human. A relationship of host and parasite instead of equally human but different individuals – a defiance of human dignity, a false uplift involving the lowering of another.

There is no exception to this formula when we look at the everyday phenomenon of Romantic kneeling. A man is always expected to be on one or both of his knees. The woman, in presumed exaltation, looks down on him, and knows that in her mind and that of the society that upholds her, that he belongs there. He is hers to use and dispose.

Flip the genders, and this would constitute some sort of toxic, abusive relationship. The fact that it is acceptable the way we see it occurring in our real world is the problem that should be addressed and challenged.

It should be considered a form of sadism for a woman to actually be delighted to be in this position, or to observe this occurrence as a third party and classifying it as joyful. Likewise, it should be considered a form of masochism for a man to partake in such fundamental submission.

Too many think that these are the sort of things men do that women should be thankful for. At the risk of once again the message falling under deaf ears, I have to make this point yet again by asking the question: why is a man groveling on his knees and debasing himself something to be thankful for?

Why is the risk to men’s well-being and sacrifice of their time, health, and very lives subject to female gratitude? Why does the belittling of one for the pedestalization of another have any place in what is supposed to be a civilized society, in which all of humanity enjoy same dignity as human beings?

The Meaning of Natural

A common response I receive when I speak out against the expectation that gynocentrism is natural goes something like the following: “I do believe it is natural, even if I am against it.”

Again, a reminder of what is meant by gynocentrism: deference to women and their needs and wants at the expense of men and their needs and wants. These people are saying this state of affairs is natural, no matter what they ultimately feel about it. In other words, biologically proper to the species.

Perhaps it is only fair to reference two contexts of “natural”: evolutionarily arrived at, and what is metaphysically meant to be. I will attempt to respond to the allegation of “gynocentric nature” from both of these contexts.

We are generally preoccupied with human reproduction as well as the survival of the species when invoking evolution in justifying gynocentrism. A favorite bromide, paraphrased, is “A man can inseminate many women and the tribe will survive, whereas the opposite is unsustainable, therefore women’s survival is more valuable than any man.”

I will remind you that too many antifeminists love this argument; beware of the ones that parrot it.

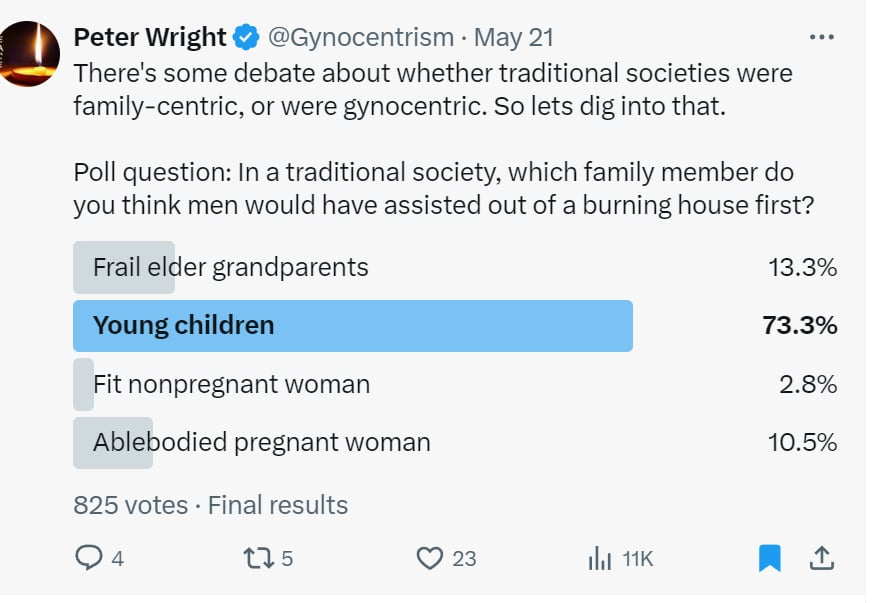

But as it turns out, if humanity was “centric” about anything, the case would be better made that it would be about the children since it is their survival that trumps both adult men and women, at least so it has socially been accepted. Even without the argument from child-centrism, both men and women are equally valuable and necessary, and men have to be highlighted now because of how they are treated as extras at best, disposable and less than human at worst.

Gynocentrism clearly prioritizes male groveling and catering to females as if they are a superhuman level of being. Either that, or the male is subhuman; regardless, the tiers are clear. Female more valuable than male. But if it rings true that men are what build society, then is vulgar to even imagine them as anything but valuable.

The question to ask then becomes this: is it biologically natural for men to be downplayed as a subspecies of human of little to no importance to the evolutionary equation? Is degradation and mortification mankind’s natural state as it is the natural state for the female of the species to treat them accordingly?

There is a sickening prospect as traditional gynocentrists indulge in this line of thinking. Observe how they refer to the “science” of evopsych propaganda to justify the existence of the gynocentric status quo, just like Nazi Germany used the “science” of racial superiority as fuel for their particular ethnic crusade. Both use a form of scientism to justify classifying one group of humans as above, and the other below.

It is important to note that there is much more to the nature of humanity than just its survival and how it reproduces. The evolution of humanity chiefly has to do with how it evolved into its current physical and social form. As I have stated, Humanity evolved to stand and walk on its own two feet. Clearly, it is a large factor in bringing the species to where it is now.

Remember, however, what Homo Sapiens means: “Thinking Man”. Thinking is more than solving math problems or recognizing landscapes or realizing that fire burns…or worse, obeying; it is about asking questions – philosophy was born with the human, as he first contemplated the reason for his limited time on Earth.

Conclusion

What, then, is natural to mankind? To stand, to think, to achieve greatness.

What is decidedly not natural to mankind? To act in contrary fashion to the meaning of mankind. To not think, in other words conform. To not achieve, in other words to berate greatness or even worse, to destroy it. To not stand, in other words, to go down on his knees and grovel.

Based on what I have stated thus far, groveling is an act of non-humanity. The same species that looks forward and up for his aspirations and goals and ultimately followed through to create wonders civilizational, technological, and creative cannot simultaneously say that he is a mere animal in subservience.

Kneeling, then, means assuming the role of the subhuman. It becomes improper for anyone, man or woman, to assume the role that which condescends another human as a subhuman role. To see a man on his knees should be met with grave concern, instead of bubbling saccharine gratitude.

Groveling to the female of the species is completely incompatible to the nature of mankind as a bipedal driver of the motor of the world, end of story. This is my response to those who say that gynocentrism is natural, no matter whether they hate it or not: we are against gynocentrism because it is not natural, but rather a social disease with no proper biological backing.

Consider then why any woman must want this. Ever since the attempt to weasel into sex-relational favoritism by way of Romantic Love and courtship, in which the first gynocentrist gave an irresistible sales pitch that says “men much be subhuman servants to holy womankind” in order to curry favor with a woman, the stage was set. Women learned to see men as marks.

This has been my case for challenging the act of the kneel as gracious or wholesome as our gynocentric world loves to insist.

The next time you see a man proposing to a woman on his knees, know that he is degrading himself no matter the outcome of the proposal. The next time you see a man kowtowing on his knees to an authority figure that may or many not be divine, he is not practicing humility in any meaningful sense but rather has integrated his unworthiness as a human.

Kneeling is a gross affirmation of man as a sacrificial animal. It is an admission that he lives for the approval of tyrants big and small.

The reason why this should be placed as a higher issue for our men’s movement is because too many who call for “real masculinity” cite kneeling as an actual masculine trait. This is a danger, and we will do well to know one when we spot one.