Teoría del Ginocentrismo

Las conferencias seminales que se encuentran a continuación fueron pronunciadas en 2011 por Adam Kostakis:

5. Anatomía de una Ideología de Víctima

Conferencia Nº 5

Entre los peores errores que un pueblo amante de la libertad puede cometer es el de estereotipar a la feministas como un pequeño grupo variopinto de lesbianas rabiosas que ha dejado de ser relevante hace mucho tiempo. Tomen nota: este estereotipo les ayuda.

Debo repetirlo: este estereotipo les ayuda.

Piensen en eso un momento. Cada vez que ustedes menosprecian a las feministas como un montón de viejas gruñonas que nadie toma en serio, han ayudado ustedes a oscurecer el programa feminista y, sin duda, su misma existencia como una forma de poder organizado. Menosprécienlas, deben hacerlo – ¡pero háganlo de una manera que las exponga, no que las esconda! Porque el feminismo está lejos de ser una reliquia del pasado. El movimiento feminista es tomado muy en serio por aquellos que tienen el poder para hacer cumplir sus objetivos:

(1) La expropiación de los recursos de los hombres hacia las mujeres.

(2) El castigo de los hombres

(3) Incrementar (1) y(2) en términos de alcance e intensidad indefinidamente.

La obscuridad ayuda en la realización de esas metas al crear dudas entre los opositores potenciales. La identificación inapropiada del feminismo como un artefacto cultural que ya no tiene ningún peso sobre las operaciones del gobierno y la sociedad es un producto de la metamorfosis del feminismo en sí. Noten que la esencia, o la sustancia del feminismo no cambiado a lo largo de los años, tan solo su forma, o su empaque. El cambio de empaque ha demostrado ser tan efectivo que ahora hay algunos que incluso niegan que el producto exista.

Por el contrario. Así como los tiempos han cambiado con el feminismo, el feminismo ha cambiado con el tiempo. En la transformación del feminismo de un movimiento en oposición al gobierno y a la sociedad en general, al un movimiento que controla al estado y a la opinión pública –y usa esa posición para perseguir a los nuevos enemigos del estado– sus estrategias se han sometido a cierto tipo de sofisticación. Hoy en día, las feministas ya no necesitan hacer rabietas para conseguir lo que quieren, porque aunque antes luchaban contra el sistema, ahora lo controlan. Este es el cambio verdaderamente profundo en las sociedades Occidentales desde el zenit de la conciencia respecto al feminismo en la mitad del siglo pasado; no es que las feministas se hayan hecho menos relevantes, sino más.

Como Fidelbogen lo puso hace poco:

El feminismo está ahora afianzado en las estructuras institucionales, y por lo tanto, es “respetable”. Se podría comparar al crimen organizado, que solía ser abiertamente grosero y hostil en los primeros días de la mafia, pero que una vez lograron poner a su gente en el ayuntamiento, y en la política electoral, aprendió a vestir corbata de seda y a jugar el juego de manera diferente.

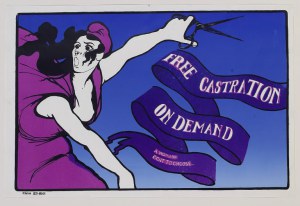

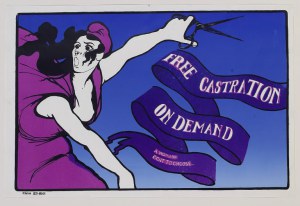

Cuando las feministas estaban fuera de la carpa, el ofender era una de sus primeras armas –pobremente disfrazada como una osada transgresión de los límites. ¿Quién recuerda esta adorable pieza de odio propagandístico, publicada en la década de 1970?

La de arriba es precisamente el tipo de cosas que las feministas de hoy en día quieren pretender que nunca pasó. Ahora que las feministas se encuentran dentro de la carpa, están obligadas a defender sus ganancias, en la década de 1970, cuando se concibió la imagen de arriba, ellas atacaban desde afuera, y buscaban tumbar la moralidad oficial en lugar de (como lo hacen ahora) definirla y dictarla.

¿Y qué mejor para mantener el control que castigando a lo que atacan, o podrían atacar, al nuevo status quo? Nos referimos claro a los hombres, que son los que más tienen que perder de los tres objetivos esenciales del proyecto feminista que ya mencionamos arriba. Hoy en día, las feministas creen que las mujeres tienen el derecho inalienable de no sentirse ofendidas, y no temen emplear la violencia de estado para imponer este derecho. Perseguir a aquellos (hombres) que las ofendan es su nueva arma, una que reemplaza a la anterior (ofender). Desde luego, perseguir a la gente simplemente porque dicha gente es ofensiva es bastante menos caritativo de lo que los hombres fueron para con las feministas antes de que éstas tomaran el poder. Pero, como nos lo explica la Teoría del Ginocentrismo, los hombres sólo eran caritativos con las mujeres ofensivas en los primeros días del feminismo porque las mujeres ya ejercían un control sustancial.

¿Creen acaso las feministas que están haciendo lo correcto? La respuesta es un inequívoco si para la mayoría de ellas –ellas realmente creen que son gente virtuosa, y que aún cuando son conscientes de estar mal, lo racionalizan de tal manera que también, simultáneamente, están bien. ¿Cómo puede ser esto posible) Bueno, déjenme mostrarles cómo funciona, rastreando la anatomía de una ideología de víctima.

Una vez que un periodo de concientización ha propagado la creencia de que los miembros de un grupo son –por su naturaleza esencial como miembros de ese grupo– víctimas, el grupo perseguirá tres objetivos:

(1) Igualarse con el grupo designado como “enemigo”;

(2) Forjar su propia “identidad de víctima”, distinto del grupo “enemigo”, al que no le tiene que rendir cuentas.

Se darán cuenta de que, mientras el primer objetivo acerca al grupo “víctima” al grupo “enemigo”, en términos de estatus, expectativas, autonomía, etc., el segundo amplia el espacio entre ambos grupos. El primer objetivo, nos dicen, nos unirá en nuestra humanidad común, y otorgará libertad a todos, y otras cosas agradables como esa. Pero tan pronto como no acercamos a ese objetivo, tiende a haber un cambio hacia proclamaciones de importancia del segundo objetivo. Nada será nunca suficiente para satisfacer al grupo “víctima”, pues éstos se ven a sí mismos como esencial e inherentemente víctimas del grupo “enemigo”, sin importar de lo que haya cambiado en realidad. Una ideología de víctima es anti-contextual, y sus seguidores ¬–las auto-designadas víctimas– nunca se verán a sí mismas como otra cosa. Su victimismo es confirmado con anterioridad, y los hechos se deben acomodar a la narración. En otras palabras, continuarán tergiversando cualquier situación para hacer ver siempre que se les trata de la peor manera.

Es por eso que feministas como Hillary Clinton se pueden salir con la suya al decir cosas como esta:

Las mujeres siempre han sido las principales víctimas de la guerra. Mujeres que pierden a sus esposos, sus padres, sus hijos en combate.

Bueno, sin duda –perder a miembros de la familiar en muertes horribles es mucho peor que tener que experimentar esas muertes horribles. Esto es, si toda su visión de mundo está manchada por el sexismo y usted reduce el estatus de los hombres a Objetos que Protegen/Proveen. En la cita de la Sra. Clinton, no se les otorga ningún tipo de humanidad a los hombres. El problema real no es que estos hombres sean traumatizados, mutilados o hechos pedazos per se; es que, como están siendo sujetos a esas atrocidades, los hombres no podrán cumplir con sus obligaciones de proteger/proveer de manera efectiva. Es por ello que son las mujeres quienes pierden, porque los hombres realmente no importan en tanto no puedan asistir a las mujeres. Este es precisamente el tipo de actitud que emerge de una ideología de víctima. Toda su existencia, en toda su maravillosa complejidad, se reduce a un primitivismo sin matices: mi gente importa, la suya no. O, como ya veremos, mi gente es buena, la suya mala. Todo lo que sea bueno para mi gente es bueno, no importa si es bueno o malo para su gente.

A este tipo de pensamiento se le conoce como Esencialismo Maniqueo, y es la piedra de toque metafísica de todo el feminismo. Décadas de concientización han asegurado que las mujeres son reflexivamente consideradas como objeto de injuria, sean cuales sean los hechos. Si no se puede encontrar ejemplos genuinos de mujeres que hayan sido agraviadas, el privilegio compensatorio se convierte en la meta aprobada. Es decir, se trata de manera más indulgente a las mujeres en un asunto porque se cree que ellas están en desventaja en asuntos no relacionados, o simplemente en desventaja en general. Un ejemplo reciente de lo anterior del Reino Unido es la orden emitida por la Dama Laura Cox a los jueces que dice que éstos deben tratar a las mujeres criminales con mayor indulgencia, una resolución que simultáneamente reduce a los hombres Británicos a un estatus de segunda clase mientras le da luz verde a mujeres abusivas que de otra manera hubieran sido disuadidas.

Hay algunas que van aún más lejos. La Baronesa Corston, quien se identifica explícitamente como feminista, cree que las mujeres no deberían ser castigadas en lo absoluto cuando cometen crímenes. Su informe de Gobierno de 2007 aboga por la clausura de todas las prisiones de mujeres, y que aún las delincuentes más violentas y abusivas no deberían ser encerradas. Sin duda, ellas

ya no irían a una de las 15 prisiones de mujeres de país, que serían todas clausuradas. En su lugar, asesinas como Rose West, quien cumple una condena por el asesinato de 10 mujeres y niñas, serían enviadas a “sencillas” unidades de custodia locales. Allí se les permitiría vivir como una “unidad familiar” con otras 20 o 30 prisioneras, quienes organizarían sus compras, presupuestos y cocina. Las unidades también les permitirían a esas mujeres permanecer cerca a sus familias…Todas las cárceles de mujeres se cerrarían en la próxima década, y en su lugar se podrían convertir en prisiones para hombres…El informe sostiene que “Hombres y mujeres son diferentes. El trato igual a hombres y mujeres no produce resultados iguales.”

El de arriba es un ejemplo clásico de la Neolengua Orwelliana. Anti-feministas de todos los tipos han venido diciendo por décadas que los hombres y las mujeres son esencialmente diferentes. Las feministas han insistido que hombres y mujeres son esencialmente iguales, y que por ello se les debe dar igual trato. Pero tan pronto como la igualdad resulta retrógrada para la meta de empoderamiento femenino, se suelta como una papa caliente, y las feministas se retuercen en una increíble gimnasia semántica para justificar ese súbito giro.

Las mujeres tampoco serán enviadas a prisión para “enseñarles una lección”.

Por supuesto que no. Las mujeres no deberían tener que aprender cómo obedecer la ley, mucho menos cómo ser miembros funcionales de la civilización. Se les debería permitir correr libres y salvajes, abusando y destruyendo todo lo que les dé la gana con absoluta impunidad. No deberían esperar siquiera una mínima amonestación por su mal comportamiento – eso sería violencia doméstica ¿acaso no lo sabía?

Pero si el feminismo realmente se tratara de igualdad, ¿no deberían las feministas tratar de pasar nuevas leyes para criminalizar a más mujeres, en lugar de su enfoque anti-igualitario de encarcelar a menos mujeres y a más hombres? ¿o es que acaso la igualdad sólo importa cuando son las mujeres las que son consideradas desiguales? (en sí mismo, esto implicaría fuertemente que las mujeres son una clase privilegiada como ninguna otra.)

La encarcelación femenina es tan sólo un octavo de la de los hombres en los Estados Unidos (Wikipedia, consultada el 10 de Octubre de 2010) mientras que las mujeres suman tan sólo el 5.7% de los reclusos en la Gran Bretaña (consultada el 10 de Octubre de 2010). Sin duda, si la igualdad fuera la meta, relajaríamos las leyes punitivas inspiradas por el feminismo en contra de los hombres, y buscaríamos castigar a más mujeres en su lugar. No se me ocurre ningún otro sector de nuestra sociedad que sea más predominantemente dominado por los hombres que el sistema penal –algo que, en aras de la igualdad sexual, necesita cambiar.

Pero no – rotundamente contrario a los principios de la justicia neutra e imparcial, las feministas consideran que encerrar a menos mujeres ¡es algo bueno en sí mismo! Es como si las mujeres que son culpables de crímenes no son realmente culpables –y por lo tanto son víctimas de lo que sea que se les haga como castigo. Es una noción popular que las mujeres están en desventaja –generalmente, inherentemente, esencialmente, con cada fibra de su ser– y por lo tanto están en desventaja en cada área particular de la vida; por ello, cualquier cosa que se pueda hacer para ayudarlas debe ser una reducción de desventajas injustas. Cualquier persona racional puede ver qué tan absurdo es todo esto, e incluyo a feministas destacadas en ese grupo, puesto que son astutas pero no estúpidas. Sólo desiertos, disuasión, trato justo, al diablo con la civilización; éste es el Ginocentrismo en acción.

Para recapitular, las ideologías de víctima, como el feminismo, buscan:

(1) Igualarse con el grupo “enemigo”;

(2) Forjar su propia “identidad de víctima”, distanciarse y no rendirle cuentas al grupo “enemigo”.

Que estos dos objetivos estén en contradicción no es solamente un error de lógica; es parte de una estrategia que le permite al grupo “víctima” cambiar su posición según lo requieran las circunstancias. Se podría perseguir el objetivo (1) durante un corto tiempo. Pero si se somete al grupo al escrutinio por colocar en desventaja al grupo “enemigo”, las “víctimas” pueden simplemente cambiarse al objetivo (2) y hacer énfasis en la importancia de su propia singularidad en maneras para las que la igualdad no es suficiente. O, como lo puso la feminista Germaine Greer:

En 1970, el movimiento era llamado “Liberación de la Mujer” o, despectivamente, “Lib de las Mujeres”. Cuando se dejó a un lado el nombre de “Libbers” por el de “Feministas” todos nos aliviamos. Lo que nadie notó es que el ideal de liberación estaba desapareciendo con la palabra. Nos estábamos conformando con la igualdad. La lucha por la liberación no se trata de la asimilación sino de afirmar la diferencia, dotando a esa diferencia con dignidad y prestigio, e insistiendo en ella como una condición de auto-definición y auto-determinación. …las feministas visionarias de finales de los sesenta y comienzo de los setenta sabían que las mujeres nunca podrían encontrar la libertad al acordar vivir las vidas de hombres cautivos.

Una vez que se alcanza un estatus igual, se puede desechar la retórica de la igualdad, porque ¿quién en todo caso quiere ser igual a un hombre? Aquí, en blanco y negro, está la declaración de la supremacía femenina.

Como ha sido siempre.

Si la igualdad hubiese sido la meta final, entonces las desventajas de los hombres habrían sido abordadas seriamente, y no exacerbadas mientras los hombres mismos eran provocados. Hasta el día de hoy, la única vez en que una feminista se molesta en abordar alguna desventaja masculina es cuando al señalarla se beneficia a las mujeres –como es el caso de la licencia por paternidad. Hacer cumplir las licencias de maternidad y paternidad descarta cualquier elemento disuasorio que los empleadores puedan tener al contratar a una mujer. Una feminista dejará de lado su treta de “todos los padres son violadores y abusadores”, justo lo suficiente como para insistir que los hombres deberían tener los mismos derechos en lo que respecta a la crianza –pero esto es presentado típicamente como una exigencia a que los hombres compartan la carga de criar a los niños para que las mujeres puedan obtener más poder en su lugar de trabajo. Aún cuando se trata de reivindicar las injusticias que sufren, los hombres no son más que herramientas para el mejoramiento de las mujeres.

Como ha sido siempre.

Otro ejemplo es la violación de hombres en las cárceles. Las feministas recalcan este problema ocasionalmente, pero sólo para mostrar que los hombres son los opresores, lo que les permite atacar a la masculinidad misma. Las feministas toman la antorcha una vez que el violador ha hecho lo suyo; ellas completan la humillación sexual de la víctima al destruir su identidad, envenenando su mente con calumnias que dicen que la masculinidad misma es la culpable por su victimización; por lo que una parte fundamental e inmutable de ese hombre víctima es la causa de violación. Ellas fuerzan sobre él la identidad de violador junto con la de víctima, su denigración de la “masculinidad tóxica” sirve para asegurarle que él comparte las características abusivas de su abusador. Por otra parte, se ignora o se niega el alto nivel de culpabilidad femenina en el abuso de niños, tanto sexual como no-sexual.

Ésta es la razón por la cual nuestra definición universalmente aplicable de feminismo no podría haber incluido ninguna referencia a la “igualdad” –no es una declaración razonable si hemos de utilizar herramientas analíticas más incisivas que el Esencialismo Maniqueo. La definición universal permanece, y es posible ceder ningún terreno: el feminismo es el proyecto de incrementar el poder de las mujeres.

¿Poder en qué sentido? ¿Poder para hacer qué? Tales preguntas surgen inevitablemente. La respuesta, si ha seguido el texto de cerca, es obvia –para lo que les dé la gana, sin importar quién más puede salir lastimado. El silencio no es consentimiento, pero es complicidad cuando se tiene el poder de llamar la atención hacia el abuso, así como los recursos para detenerlo, pero aún así se fracasa en hacerlo si los abusadores tienen genitales parecidos a los suyos.

Y es a esto a lo que hemos llegado, amigos – estamos lidiando con primitivos en traje de pantalón.

Adam

* * *

6. Vino Viejo, Botellas Nuevas

Conferencia Nº 6

“Lo que sea que destroce la individualidad es despotismo, no importa con qué nombre se le llame” – J.S. Mill

Dominación. Mucho del análisis feminista gira en torno a este concepto. Un hombre que golpea a su mujer no está simplemente molesto con ella; está intentando dominarla. Un hombre que no está de acuerdo con una mujer y habla por encima de ella no está simplemente siendo grosero; está tratando de dominarla. Un violador realmente no está preocupado por el sexo; su crimen es una exhibición de poder, tan sólo quiere dominar a la mujer.

Verán, el hecho de que estas cosas sucedan no es suficiente para las fanáticas anti-hombres del mundo. Ellas siempre necesitarán más abasto para el molino misándrico. Castigar a los verdaderos criminales es una cosa, pero sencillamente no es tan gratificante como podría serlo dejar las cosas ahí – ellas necesitan articular lo que su intuición de mujer siempre les ha dicho, y es atacar a todos los hombres. El problema es, por supuesto, que la abrumadora mayoría de hombres no atacan a las mujeres de ninguna manera perceptible en lo absoluto. La solución, como se han dado cuenta las feministas, es jugar al Dr. Freud y plantear alguna motivación subconsciente, subyacente – una mentalidad oscura, sexual, anormal, que actúa como una explicación universal del comportamiento masculino.

Incluso cuando los hombres no se dedican a actos criminales, la criminalidad sigue allí, simplemente es latente – o es lo que las feministas nos quieren hacer creer. La idea según la cual todos los hombres poseen un mal latente, inherente, y las mujeres no, funciona como un pretexto para todo el discurso de odio sexista contra los hombres. Lo vemos en el trabajo, en las diatribas sin sentido en contra de una “cultura de violación” que no puede ser refutada, en campañas para prohibir el consumo privado de pornografía, y en la defensa de mujeres maliciosas que acusan falsamente a hombres de crímenes sexuales. Consideremos esta declaración de Mary Koss: “la violación representa un comportamiento extremo pero que se encuentra en flujo continuo con el comportamiento masculino normal dentro de la cultura.”

La desviación masculina inherente, según dicen (o insinúan), se manifiesta como un flujo continuo de masculinidad disfuncional, abarcando todo desde una simple desavenencia verbal hasta el asesinato del cónyuge. Todas las acciones masculinas que no contribuyan al proyecto feminista – incrementar el poder de las mujeres – se deben tomar como evidencia de una masculinidad inherentemente defectuosa que busca, sobre todo, dominar al bello sexo.

Pongámoslo de esta manera. ¿Dirían ustedes que ser asesinado ayuda a incrementar el poder de las mujeres?

¿No?

Bien, ¿qué me dicen de perder un combate verbal? ¿Esto ayuda a que la mujer incremente su poder? ¿O no? Sin duda parece que uno tendría más autonomía si ella puede convencer más fácilmente a los demás que su parecer es correcto.

Entonces, si los dos ejemplos anteriores existen en un flujo continuo en el que las mujeres pierden poder, el corolario del cual es la dominación patriarcal, entonces por supuesto que es culpa de los hombres. Esto es, si nuestro análisis está basado en dudosas conjeturas feministas.

El concepto de dominación, tan tomado por sentado en su manifestación presente, es un ejemplo supremo del cambio lingüístico que ya discutí previamente. Como término, conlleva contrabando ideológico, escondido en un abrigo de rectitud. Originalmente, el término dominación, que tiene su raíz en el latín dominus, se refería específicamente al poder ejercido por un amo sobre sus esclavos. Como tantos otros términos de los que las feministas se han apropiado con el fin de manipular las percepciones de la realidad, dominación se ha vuelto objeto de un descoloramiento semántico.

Lo que es realmente interesante de todo esto es que nuestro nuevo concepto de dominación –como jerarquía injusta que se debe atacar y a la que hay que oponerse– se usa en una dirección específica: como promotor del verdadero despotismo. La señal más obvia que marca el camino al despotismo es la intrusión de la esfera pública en la vida privada de los individuos. El despotismo es precisamente el tipo de jerarquía injusta con la que identificamos a la dominación; sin embargo, si se amplía lo suficiente este último término como para abarcar todas las áreas de la vida privada, entonces el resultado inevitable es una dictadura brutal y devastadora.

Este es el contexto en el que debemos entender el eslogan feminista que ha perdurado por más tiempo: lo personal es político. Nótese que (según ese eslogan), lo personal no es simplemente un asunto que interesa a lo político; no forma parte de lo político; no es de importancia equivalente a lo político. Realmente es lo político.

Los dos términos son presentados como si fueran idénticos, intercambiables.

Lo personal es político.

Si esto es cierto, entonces no existe ni el más pequeño espacio de privacidad, que es algo que corresponde exclusivamente al individuo –es decir, sobre el cual el individuo es soberano. Es cierto que una vida privada digna de su título no sería posible sin una estructura pública dominante –es la ley la que protege todas las libertades que hace posible la existencia de las vidas e intereses privados. Para usar la analogía favorita de J.F. Stephen, la ley es la tubería a través de la cual fluyen las aguas de la libertad. Es cuando la vida pública –el estado– fracasa en reconocer sus propios límites que la sociedad se ve amenazada por el despotismo.

Los intelectuales de todas la épocas han elaborado las razones más ingeniosas por las que su manera de pensar en superior a aquellas que han existido antes. La mayoría de la gente sencillamente ha asumido esto sin la necesidad de que se lo justifiquen. Lo que es peculiarmente moderno es la construcción de fronteras artificiales entre nuestro tiempo y las épocas pasadas. Nosotros, por ejemplo, no consideramos que estemos viviendo en el mismo plano histórico que los de la Europa Medieval, ni mucho menos de la Grecia Antigua. Éstos son tiempo inexplicables e inaccesibles para nosotros. Es una fantasía seductora con la que nos liberamos de cualquier miedo conjurado por los horrores de los libros de historia. Nos gusta creer que las autocracias sangrientas se encuentran confinadas a esas páginas, y que cosas como esas no podrían pasar aquí, ni ahora; no en la vida real. Sin duda, hemos progresado más allá de todo ello. Nosotros somos Iluminados, a diferencia de los seres humanos que existieron antes de nosotros.

¿Pero acaso no estamos nosotros en el mismo plano histórico que vio surgir al Comunismo Soviético y al partido Nazi? Estos reinados del terror en particular ocurrieron en el último siglo, no importa qué tanto nos gustaría pensar que hemos progresado más allá de ese barbarismo. Supuestamente, nosotros en el mundo Occidental aborrecemos los regímenes totalitarios; y sin embargo el surgir de esos dos que acabamos de mencionar es indicativo de una tendencia que existe dentro de nuestra cultura política. Junto con el bagaje que hemos heredado de la Ilustración se encuentra el concepto de utopía. El término fue acuñado en el siglo XVI, y designaba, por primera vez, la noción de un orden socio-político perfecto. Con el nacimiento de esta idea, se sembraron las semillas para la limpieza de impedimentos humanos como un programa político puesto en marcha.

Antes de la Ilustración, se asumía que la vida humana era cíclica. Tan cierto como que el sol sale por la mañana y se oculta una vez más al anochecer, los grandes poderes surgirían y caerían, para que otros nuevos tomaran su lugar. Esa era la ciencia de Polibio, cuya obra histórica no disponía los eventos en orden cronológico, sino que representaba la experiencia humana como una unidad. Las dinastías, imperios, culturas, así como los pueblos y sus comunidades, vivían y morían en las oscilaciones del péndulo cósmico.

Una de las mayores innovaciones conceptuales de la modernidad es el progreso como ideal guía en la política y la sociedad. No solo asumimos que estamos constantemente distanciándonos de nuestra propia historia; persiste la creencia de que sólo es cuestión de tiempo antes de que cada problema dé lugar a su solución. La fe en el conocimiento humano nunca ha sido tan grande como en la Era de la Información; nosotros buscamos activamente vencer lo que antes se consideraba como los hechos inextricables de la vida.

El propósito de esta digresión no es sembrar dudas sobre las posibilidades del conocimiento humano, ni sugerir que cualquier intento por mejorar la condición humana es una búsqueda innoble. Es para señalar que somos hijos de la Ilustración, independientemente de cuál es nuestra inclinación dentro del espectro político. Es para señalar que hay ciertas suposiciones que forman la base y el andamiaje del pensamiento político Occidental, y que es sobre estas suposiciones que están construidas ideologías tan diversas como el conservadurismo, el liberalismo, el Nacional Socialismo y el feminismo.

El –ismo en sí es un fenómeno completamente moderno. Un –ismo (o, podríamos decir, una “ideología”) asume una diferencia entre cómo la sociedad es y cómo debería ser, predicado sobre una perspectiva moral del mundo. Esto es obviamente verdad para aquellas ideologías que abogan explícitamente por un cambio –liberalismo, socialismo, feminismo, y así. Es igualmente cierto para el conservadurismo y el tradicionalismo, ideologías que (como ellas mismas lo ven) apuntan a recuperar aquellas cosas valiosas que se han perdido a través de las épocas.

Típicamente, lo que las ideologías encuentran tan censurable acerca del mundo es la configuración vigente de poder. Los grandes textos y oradores de la ideología que describe una configuración de poder pelean porque ésta se reconozca como injusta, y luego presentan los medios a través de los cuales se puede lograr el cambio deseado. Estos medios pueden involucrar el trabajar a través de las instituciones estatales vigentes, o puede que éstas necesiten ser derrocadas, o puede que se eviten las prácticas convencionales y se abogue por encantar a la sociedad civil.

Lo que sea que la ideología suponga en práctica, esta es una diferencia marcada con lo que ocurría antes. El progreso, no la recurrencia, se encuentra en la raíz de toda expectativa política. Ya sea un progreso hacia una sociedad sin clases, o pureza étnica, o el retorno a los valores tradicionales, el progreso es una constante. La perspectiva de que algo está mal y se necesita hacer algo al respecto, como una declaración política, es un invento reciente, uno que define nuestra cultura política compartida. Los conservadores se encuentran atrapados en la misma telaraña “progresiva”, pero también los iconoclastas, quienes evidencian su cumplimiento de los modos convencionales de pensamiento aun cuando declaran sus intenciones de alejarse de ellos. Entre más luchan contra esta inevitabilidad, más atrapados se encuentran. Para poner un ejemplo relevante, las feministas han declarado a veces que ellas se están distanciando completamente de las suposiciones “patriarcales”, y construyendo su propia visión de mundo desde cero, que no está corrompida por la influencia masculina. En realidad, nadie empieza desde cero, y el feminismo continúa profundamente incrustado en formas de pensamiento que han evolucionado a lo largo de los siglos, exclusivamente a través de las mentes de los hombres. La ideología feminista, y todas sus innovaciones, sencillamente no pudieron haber ocurrido sin previos siglos de trabajo masculino.

La conferencia de la próxima semana mirará más de cerca la afirmación feminista según la cual lo personal es político, y las implicaciones ocultas contenidas dentro de este lema. En las semanas que vienen, consideraremos el concepto de utopía, que esta vez fue mencionado por encima. Por ahora será suficiente un comentario breve: utopía es la extensión lógica del progreso, y ese es el fin de todo progreso, la última etapa de la existencia humana. Es una idea profundamente peligrosa, responsable de los más opresivos regímenes y de las revoluciones más sangrientas que ha conocido el mundo. Mientras la gloria y el poder personales pueden haber sido la fuerza motivadora detrás de las acciones de individuos despóticos incluso en los últimos tiempos, fue la visión colectiva y utópica la que incitó a sus seguidores a llevar a cabo las más violentas fantasías. En todos los casos en que los utópicos toman las riendas del poder, los seres humanos que no encajan en su visión de un nuevo orden mundial son tratados como la basura viviente de un régimen desaparecido.

Es con asco y horror que el Occidente mira hacia atrás a los déspotas utópicos del siglo XX, y sin embargo estos despotismos particulares corresponden a una tendencia que forma la infraestructura de nuestra propia política. Pero el asco y el horror son suficientemente reales, y quizás el cambio más verdaderamente progresivo de los últimos tiempos es el rechazo al extremismo, en todas sus formas, por poblaciones determinadas a dejar atrás un siglo de genocidio.

No obstante, eso no es tan fácil. Se puede tirar de las puntas y talar los troncos de la tierra, pero a menos de que se desentierren las raíces, pronto se verá brotar de nuevo esas flores. El utopismo, con la purificación de los impedimentos humanos que siempre implica, está codificado en nuestro ADN político. El desprecio generalizado hacia esos recientes totalitarismos fracasados no hará que lo anterior desaparezca; tan sólo puede hacer que la tendencia despótica se quede dormida por un tiempo. Un nuevo despotismo sólo puede emerger si lo hace silenciosamente, disfrazado como algo diferente –tal vez como una oposición organizada a ciertas formas de dominación injusta, cuya solución siempre es incrementar el poder del estado relativo a la autonomía del individuo.

Lo personal es político, dicen las feministas.

Ya puedo escuchar que se acerca la marcha a paso de ganso.

Adam.

* * *

7. Lo Personal, en Contraste con lo Político

Conferencia Nº 7

“Ellos se enorgullecían de pertenecer a un movimiento, a diferencia de un partido, y un movimiento no estaba atado a un programa” – Hanna Arendt

La semana pasada miramos cómo el concepto de dominación se ha convertido en una justificación para transgredir hacia el despotismo. No debería ser una sorpresa para aquellos lectores atentos que virtualmente cada palabra clave en el léxico feminista se usa de una manera similar. Ya sea que el término que se está discutiendo sea misoginia, o violación, o patriarcado, la tendencia es ampliar su significado hasta cubrir el área semántica más amplia posible, contrabandeando la máxima cantidad de alijo ideológico posible dentro de un abrigo de rectitud. El efecto en el mundo real de todo esto es restringir la autonomía masculina a través de la criminalización de las acciones de los hombres. Las posibilidades ilimitadas del descoloramiento semántico corresponden con las vastas sentencias a prisión y multas descomunales. La intención es criminalizar la norma. Cada movimiento que un hombre haga debería ocasionarle escalofríos, forzarlo a mirar sobre sus hombres, con una expresión de pánico, y preguntándose “¿Qué ley he roto ahora?” los hombres deberían vivir en un estado perpetuo de vigilancia y culpa presunta – una existencia panóptica en la que son repetidamente reprendidos por hacer las cosas mal. Es decir, según un estándar moral ajeno e invasivo que ellos son invitados a obedecer, no a entender, y ciertamente no a cuestionar o a refutar.

Pero cuando el comportamiento criminalizado cae dentro del campo de las acciones que tanto hombres como mujeres realizan, el argumento requiere un corolario según el cual es diferente, y peor, cuando los hombres lo hacen. Por ejemplo, ciertos individuos desagradables de ambos sexos cometen acoso sexual, pero nosotros tenemos que entender que cuando los hombres se lo hacen a las mujeres, es aceite, y cuando las mujeres se lo hacen a los hombres es agua. Ambas cosas, se nos asegura, con incomparables, no importa cómo vea las cosas un hombre que ha sido victimizado– después de todo, incluso en su victimismo, él tiene su percepción cegada por su privilegio.

Todo el cuento de hadas se puede resumir en el mantra feminista, lo personal es político. Como se discutió la semana pasada, el contexto propio en el que esta declaración debería ser vista es la historia reciente del mundo Occidental. Hay que darle atención particular a una corriente dentro de nuestra cultura política compartida que ha provocado gobiernos despóticos y amenaza con hacerlo de nuevo. ¿Cómo más podemos interpretar una declaración según la cual todas las cosas dentro del dominio del individuo son en realidad asuntos del gobierno? Si no poseemos, ni tenemos el control de, aquellas cosas que son personales para nosotros, no puede haber nada de lo que podamos hablar que controlemos o poseamos, incluidas nuestras vidas.

Pero sería un error ver ese mantra simplemente como una declaración o una creencia, es decir que la persona que lo dice simplemente cree que lo personal es lo político. Todo tipo de personas tienen todo tipo de teorías excéntricas, y un grupo de gente que comunica su creencia de que todos los aspectos de nuestras vidas son manejadas por el estado sería tan problemático como aquellos teóricos de la conspiración que usan sombreros de papel aluminio o la Sociedad de la Tierra Plana. Cuando una feminista dice que lo personal es político, sin embargo, ella no está simplemente enunciando una creencia; está haciendo un llamado a la acción. Hay implicaciones ocultas en esa frase.

La discusión de la semana pasada incluyó una sección sobre ideologías, y las suposiciones progresistas que se encuentran en las raíces de la cultura política occidental. Para recapitular, las ideologías asumen una diferencia entre cómo es la sociedad y cómo debería ser, predicada sobre una perspectiva moral específica del mundo. Lo que esto significa, en lo que le incumbe al análisis feminista, es que actualmente lo personal no es político, entonces se debería hacer que lo sea. Prácticamente, toda la innovación política consiste en convertir esas cosas que son personales en asuntos políticos. El extremo lógico se encuentra allí donde no hay acciones estrictamente personales, no hay afirmaciones, intenciones, pensamientos o creencias personales; todas éstas, ya sean expresadas públicamente o en privado, serían estrictamente políticas. Cada decisión, hasta los detalles más minúsculos de la vida diaria, se vuelve asunto político del que los individuos deben rendir cuentas, no como transgresiones individuales, sino como miembros de una clase opresiva que debe responder por sus pecados.

“Lo político” es otro de esos conceptos esencialmente polémicos –en otras palabras, es uno de esos conceptos que son más vulnerables al abuso. Es una idea imprecisa, que puede ser captada pero nunca determinada con precisión– y los intentos para hacerlo son como intentar agarrar el aire de un colchón inflable. Una de las cosas que podemos decir sobre “lo político” es que no siempre ha sido identificado con “lo ideológico” –lo que parece sensato, ya que “lo ideológico” es un producto de la modernidad, un recién llegado en lo que a la política se refiere.

Hubo una vez en que “lo político” era un término que se refería a Reyes, Reinas, cortesanos y nobles, sus luchas y sus sucesiones; pero ciertamente no a la doctrina. Ese cambio se dio a cabo gradualmente, con el declive del fervor religioso que marca a la modernidad.

Soy consciente de que estoy muy cerca de caer en una falacia etimológica, así que déjenme aclarar que es lo que estoy argumentando. No estoy reclamando que haya un significado apropiado de términos como “lo político” que ha pasado de moda. Ya he reconocido previamente que el lenguaje está en un flujo perpetuo. Como corolario, reconozco que las definiciones objetivamente correctas son una rareza. Mi propósito, al resaltar el cambio lingüístico, es resaltar complementariamente el cambio social. Uno rara vez sufre un cambio de paradigma sin afectar al otro. Hay un poder inmenso en el lenguaje, no sólo al reflejar sino al definir el mundo experiencial. Si queremos entender porqué las cosas con como son, debemos fijar nuestra atención en los cambios históricos en el vocabulario –es ahí donde encontraremos las nocionales células germen que dieron origen a la enfermedad del feminismo.

Ese es el caso de “lo político”. Hoy en día, todo lo que sea controversial es reflexivamente considerado como un asunto político. Ya sea que estemos discutiendo el estilo de vida inusual de alguna persona, o una nueva obra de arte que desafía los límites, o una página web que propone una perspectiva del mundo innovadora, nos sentimos bastante seguros de que lo que estamos discutiendo es una declaración política. Lo controversial es entonces político; o quizás sería más exacto decir que lo inusual es político. Se incita a los inconformistas de todo tipo a adherir algún propósito político a sus acciones o creencias. El efecto de este desafío tan público es encerrar a los individuos en un sistema de control ubicuo; salirse de los límites lo convierte a uno en un blanco.

Y esto es precisamente lo que el feminismo requiere –que los hombres se alineen, y que persigan a los que no lo hagan. Es mucho más fácil lograr el proyecto de aumentar el poder de las mujeres cuando uno puede silenciar a aquellos que tienen más que perder en caso de que el proyecto tenga éxito.

El otro lado de la moneda es el beneplácito “compensatorio” cada vez más mayor que se les da a las mujeres. Son solamente las vidas privadas de los hombres las que deben estar atrapadas en un sistema de control público; las mujeres, por otra parte, han de disfrutar del botín de la victoria en una nueva era de anarquía sexual femenina. Quizás el único consuelo que nos queda, siendo realistas, es que los despotismos son grandes generadores de iluminación espiritual entre los oprimidos. Fue la persecución de los primeros cristianos lo que llevó a hombres y mujeres piadosos a vivir solos en el desierto, imitando a Jesús –fue tan sólo en el siglo V que la Iglesia se apropió de estos monásticos, después de que hubieran buscado una existencia puramente asceta como alternativa del mundo material que los había expulsado. De manera similar, los regímenes opresivos del periodo Helenístico llevaron a muchos, dentro de las ciudades-estado griegas, a acogerlas filosofías místicas que abogaban por el rechazo del mundo. Dado que nosotros vamos en camino hacia un despotismo feminista, no es de sorprenderse que un desarrollo paralelo se esté incubando, en la forma del movimiento Hombres que Siguen Su Propio Camino (MGTOW [Men Going Their Own Way]). Los MGTOW han rechazado la exigencia ginocéntrica según la cual los hombres deben definirse de acuerdo a su destreza sexual. Como consecuencia de haber sido aliviados de ese peso, muchos MGTOW han asumido una deliberación introspectiva sobre la naturaleza del hombre y la masculinidad –discusiones que son androcéntricas, y por lo tanto no rinden cuentas a la ortodoxia feminista. En su núcleo, el movimiento MGTOW se aparta del mundo –del matrimonio, de los hijos, de los empleos sacrificantes, incluso de cualquier relación con mujeres– buscando calma de los agentes hostiles, así como lo hicieron los ascetas y místicos del mundo antiguo.

Aunque yo respaldo el estilo de vida MGTOW, soy consciente de que no es suficiente –para la realización o para la supervivencia. El feminismo simplemente no está en el negocio de dejar a los hombres en paz. Es una ideología progresista, lo que quiere decir que seguirá creciendo, sin ningún control interno sobre sus propias actividades; ¡no tiene frenos! Cualquier intento de auto-criticismo da paso a una mayor radicalización. Incapaz de percibir el mundo desde fuera de la burbuja feminista, sus discípulas piensan y actúan de una manera anti-contextual y abstracta. El único control sobre las actividades de semejantes ideologías debe venir de afuera –es decir, del resto de la sociedad. Si el feminismo no desacelera y se detiene voluntariamente, entonces les corresponde a agentes externos construir un muro de ladrillo en su camino. Este es un requerimiento moral –la alternativa es permitirle que reine libremente, en cuyo caso terminaremos inevitablemente en un despotismo. Hasta ahora, el feminismo ha mostrado ser notablemente socio-dinámico, y no se ha enfrentado a mucha resistencia política –lo que quiere decir que la velocidad de persecución va a aumentar.

Me gustaría aclarar algo. La palabra “feminismo” se puede referir a más de una cosa. De manera más obvia, feminismo como movimiento no es precisamente lo mismo que el feminismo como ideología; de manera más precisa, el primero es motivado por las máximas del segundo. El feminismo como ideología es una ideología de víctimas, lo que quiere decir que existe en defensa de un cierto tipo de gente que se ha designado como las víctimas. Los objetivos duales de una ideología de víctimas son, como ya lo había mencionado anteriormente:

(1) Igualarse con el grupo “enemigo”;

(2) Forjar su propia “identidad de víctima”, diferente del grupo “enemigo” y al que no tiene que rendirle cuentas.

Si se logra el objetivo (1), entonces la ideología sencillamente deja de existir, lo que quiere decir que el movimiento deja de existir. El movimiento, sin embargo, no es una entidad inorgánica que cumple de manera mecánica con las necesidades de la ideología. Está conformado por gente que se ha vuelto dependiente de él, tanto financiera como psicológicamente. El fin de la desigualdad, como sea que se hubiera medido al principio, significaría un desastre para las graduadas en Estudios de Género en todo el mundo. Por ejemplo, la inhabilidad de las organizaciones feministas en admitir que los índices de violación están en declive y que las acusaciones falsas están llegando a niveles de epidemia significaría grandes pérdidas que afrontarían los ideólogos que trabajan en los centros de asistencia a víctimas de violación (que generalmente se encuentran vacíos). No se puede permitir que la ideología muera –hay demasiado en juego, en particular el movimiento, y todos aquellos recursos de los que sus actores principales hayan podido echar mano. Así como con mucha otra gente, la amenaza del desempleo es suficiente como para sacar un conservadurismo radical, que insiste, en este caso, en la existencia de nuevos tipos de opresión que aún se deben superar. Hay muchísimo dinero en el negocio de la percepción constante de las mujeres como seres en desventaja. El feminismo ya no es simplemente un movimiento, sino una industria –bien llamada por muchos la industria de los agravios sexuales.

En caso de que está industria se derrumbe, dejaría un vacío en las carteras de las feministas profesionales casi tan grande como el vacío que dejaría entre sus orejas. La alternativa a un apoyo estatal continuo para superar las nuevas opresiones es casi inimaginable. No sólo significaría el fin del subsidio que se extrae a los hombres para su propia persecución –también amenazaría con dejar un vacío físico en la mente de muchas feministas profesionales. ¿Qué harían entonces, una vez que se les quite ese dinero ensangrentado?

Las feministas tienen, desde luego, un plan de contingencia. Los remito al objetivo (2). La razón por la cual las ideologías de víctimas tienden a no morir fácilmente cuando se ha logrado la igualdad, o incluso la supremacía del grupo “víctima”, es esta: porque cambian sus objetivos hacia la separación inherente entre los grupos de “víctimas” y “enemigos”, y rehúsan tomar cualquier tipo de responsabilidad para con el resto del mundo. Sin duda, cualquier intento de una persona externa al grupo designado como “víctima”, de hacer a los miembros de ese grupo responsables por sus transgresiones, es mancillado como un intento de frenar el objetivo (1) –y la persona que se atrevió a quejarse será insultada con todo tipo de nombres.

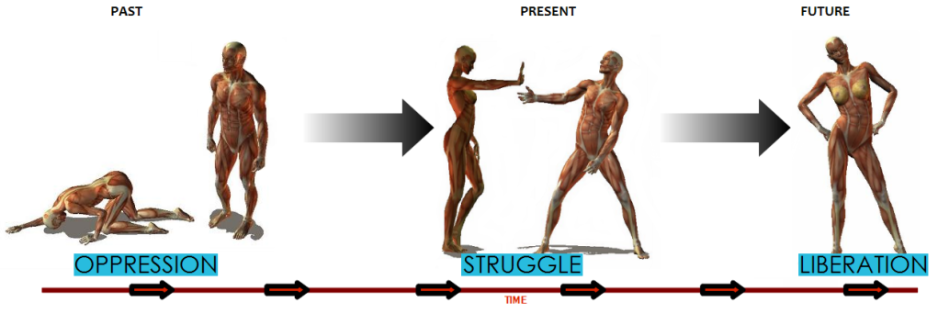

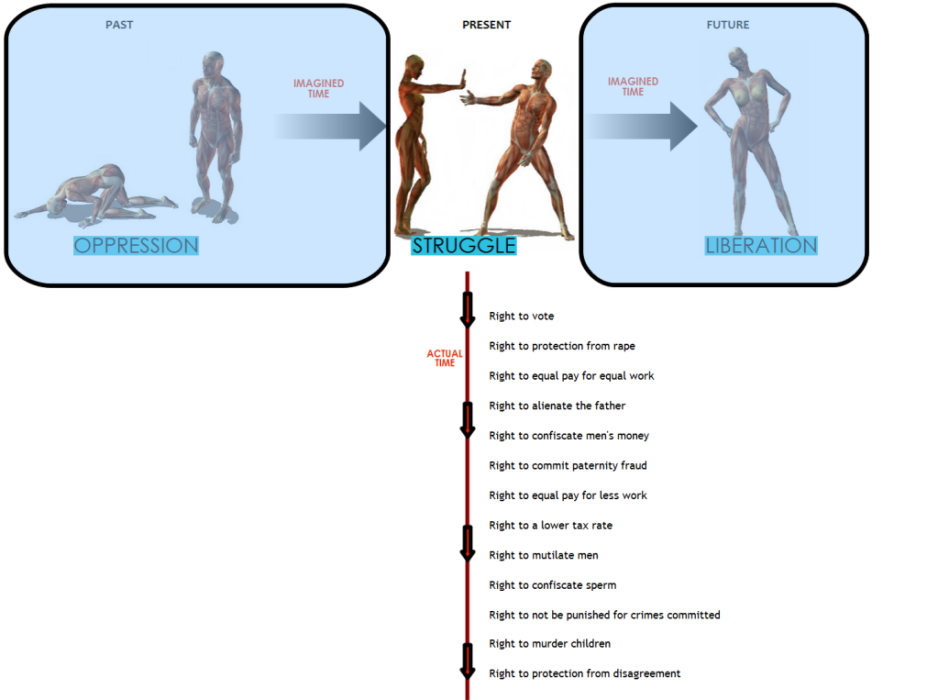

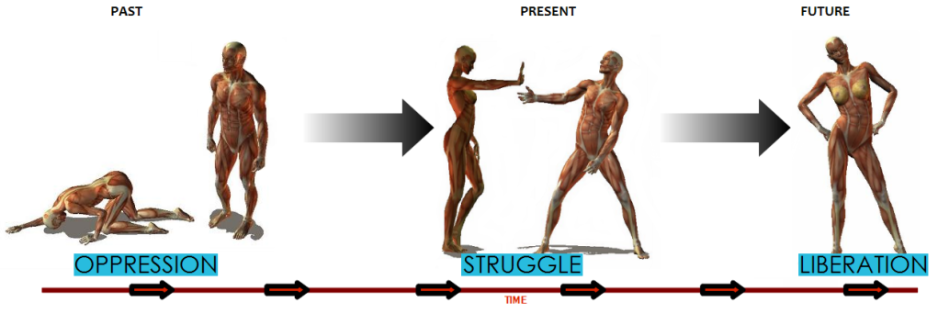

Una ideología de víctimas es necesariamente tripartita en su entendimiento del tiempo. El pasado es identificado con la Opresión, el presente con la Lucha, y el futuro con la Liberación. La historiografía tripartita es constante. Si cualquiera de los tres estados –Opresión, Lucha o Liberación– es removido, entonces no tenemos una ideología de víctima. Se derrumba debido a su inconsistencia. Tiene que haber una Opresión pasada, pues esto justifica la Lucha presente, que también tiene que existir en el presente, como una tautología; ¿de qué más estaríamos hablando? La Lucha debe ser en pos de algo, y ese algo es la Liberación, prometida en el futuro. Abajo hay una especia de diagrama, presentado desde la perspectiva feminista:

Es una caricatura infantil, apropiada para una perspectiva de mundo infantil. Es importante mencionar lo que se requiere para que la triada Opresión, Lucha, Liberación tenga sentido –el actor que lleva a cabo la opresión, contra quien se debe luchar, y de quien las víctimas designadas deben liberarse. Ese actor es, desde luego, el hombre.

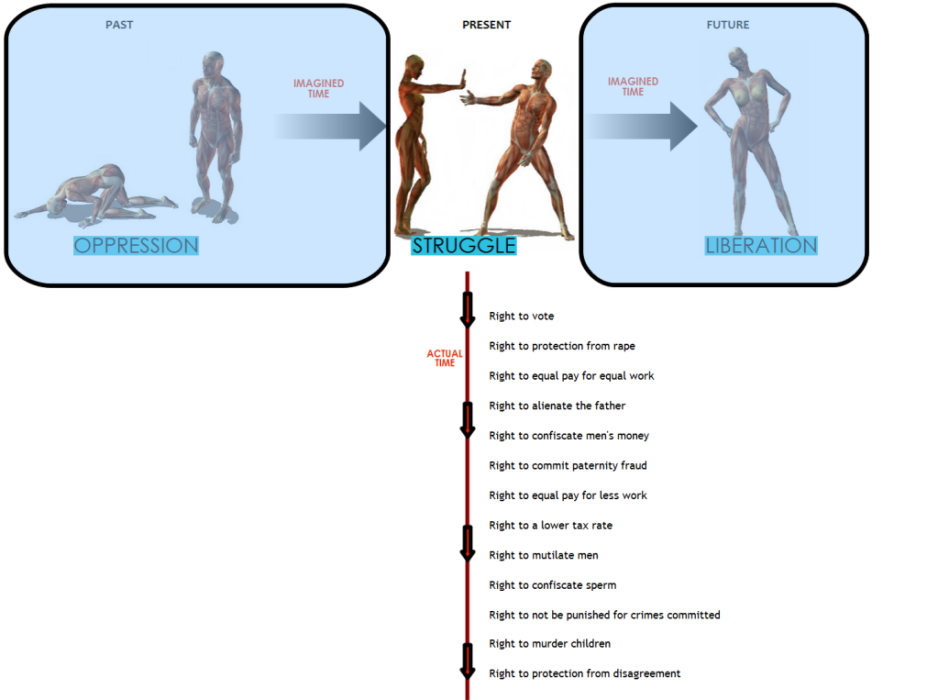

La imagen de arriba se presenta desde la perspectiva feminista, en la que el tiempo se mueve de manera horizontal, de izquierda a derecha. En el mundo real, la línea de tiempo está rota. Estamos permanente congelados en la fase presente, y desde allí, el tiempo se mueve verticalmente y hacia abajo:

Hay sencillamente demasiadas personas que se benefician del feminismo (por ejemplo, la industria de los agravios sexuales) para permitir que la verdadera liberación de la mujer sea reconocida. Si se admitiera que las mujeres no sólo han sido liberadas, sino que han recibido varias ventajas sobre los hombres, entonces el movimiento y la ideología, y por lo tanto la industria que es el feminismo, se volverían irrelevantes. El papel actual de las mujeres, que puede ser descrito de la manera más apropiada como Privilegiado, no es ni siquiera concebible en el tiempo feminista. La Liberación debe permanecer siempre como una meta futura, y no se puede permitir que sea percibida como un logro presente. El feminismo es auto-sostenible de esta manera –al impulsarse a sí mismo hacia nuevas Luchas. El entendimiento tripartito del tiempo es independiente del contexto; es fundamentalmente abstracto y anti-contextual. Se asume la triada antes de que la verdad acerca del mundo sea establecida en cualquier momento, y los hechos del mundo deben ser martillados hasta que adquieran una forma amigable a la perspectiva feminista.

No importa mucho que las grandes Luchas hayan sido ganadas. Las feministas pueden simplemente crear unas nuevas. Y como los hombres son (como debe ser siempre) los opresores contra los que se debe luchar, es bastante justificable quitarles cualquier poder que aún posean.

Hasta que no posean ninguno

Adam

* * *

8. Persiguiendo Arco Iris

Conferencia Nº 8

“La igualdad, entendida correctamente como nuestros padres fundadores la entendían, lleva hacia la libertad y a la emancipación de diferencias creativas; entendida de manera errónea, como ha sucedido trágicamente en nuestro tiempo, lleva primero a la conformidad y luego al despotismo.” –Barry Goldwater

¿Qué es lo que nos permite vivir vidas significativas? Esta es una pregunta que tiene una larga historia, y después de más de dos mil años de rascarnos la cabeza, nuestra especie no es mucho más sabia. Las respuestas fracasan tan fácilmente como se forman. Tal vez la única sabiduría real impartida por siglos de búsqueda espiritual es que la solución no se puede reducir a la materialización de un único valor. Los esfuerzos para ocasionar un sistema social basado en la materialización de un valor en particular –ya sea una doctrina religiosa, la voluntad de la nación, o igualdad social– han resultado invariablemente en una represión extendida, y no en la época dorada de paz y virtud como lo postulan sus ideologías. Por el contrario, esas sociedades que han logrado crear y mantener un espacio para que la gente pueda realmente vivir lo que podrían llamar “vidas significativas” son aquellas que han mantenido un número de valores en equilibrio. Esta no es una solución muy emocionante, pero es mejor sentirse insatisfecho con los grandes misterios de la vida que ser un siervo o un “desaparecido” por un régimen que persigue una máxima más seductora.

Sea cual sea el caso, el argumento a favor de la autonomía parece convincente –equilibrado, como debe ser, respecto a otros valores. Es difícil ver cómo la vida podría ser significativa allí donde no se poseen los derechos más básicos de auto-determinación. En este punto, estoy superficialmente de acuerdo con las feministas, quienes han hecho de la autonomía (y no la igualdad) su principio guía. Desde luego, en su caso, la única que cuenta es la autonomía de las mujeres, y ésta se debe extender tanto como sea posible. Sin embargo, coincidimos en que la autonomía, en sí misma, es algo bueno, aunque yo añadiría el corolario de que ésta debe estar en equilibrio respecto a otros valores de manera que no se vuelva una autorización parar hacer cualquier cosa.

Es entonces una ironía espectacular el que, en tanto sigan siendo feministas, las mujeres nunca podrán saborear la libertad. El feminismo es una ideología de víctima que paraliza a las mujeres en una Lucha perpetua; no se puede permitir el disfrutar la Liberación, pues de lo contrario se acaba el juego. Para seguir jugando, las feministas deben imaginar que están bajo el control de fuerzas externas que son responsables del destino que les acaece, y tienen un nombre para este delirio masivo: El Patriarcado. Cada mala decisión, cada consecuencia no deseada, cada menor inconveniente puede ser rastreado a este sistema de control místico, mítico e invisible que ejerce su influencia sobre las mujeres, de manera similar a como las tribus animistas explican varios fenómenos climatológicos a través de deidades enfurecidas y vengativas. Si las feministas han de pretender que la Lucha aún es relevante, entonces no se puede admitir que las mujeres tienen el control de sus propios actos, puesto que ello implicaría que son agentes morales libres. Se debe hacer creer a las mujeres que son delicadas embarcaciones arrojadas a una tormenta en el océano, sin tierra a la vista, en la que tratar de navegar o conducir es inútil. Tal vez podríamos contrastar esto con el movimiento MGTOW, que asemeja a una serie de canoas, ligeras pero resistentes, cuyos ocupantes reman en mares calmos –por lo pronto, al menos.

Aun cuando las mujeres sean privilegiadas más allá de sus sueños más salvajes –lo que es inconcebible en la teoría feminista– todavía no se pueden considerar libres. A las mujeres no se les permite disfrutar la libertad; se les debe negar de manera que la ideología sobreviva. Se debe reiterar, hasta que venga a la mente como si fuera un reflejo, que “todavía vivimos en un patriarcado”, y que “las mujeres todavía no son iguales”, etcétera. Las adherentes la feminismo no pueden descansar jamás, porque ellas mismas no se lo pueden permitir. Están persiguiendo arco iris perpetuamente.

Han construido una barricada mental, cerradas al mismo mundo al que le imponen sus designios. Están forzadas a concebirse a sí mismas como en una Lucha eterna, a menos de que se Liberen, en cuyo caso se volverían irrelevantes. Como lo dije la semana pasada, una percepción tripartita de la historia (el pasado como Opresión, el presente como Lucha, el futuro como Liberación) es una constante del feminismo, y todo esto se decide antes de los hechos. Sin importar el contexto, el presente es Lucha, con la Liberación perpetuamente establecida en algún punto en el futuro. Como lo dice el proverbio, el mañana jamás llega.

Como lo mencioné previamente, el feminismo es fundamentalmente anti-contextual, tomando decisiones respecto a lo que sucede antes de que suceda, y luego acomodando los hechos a dichas decisiones. El proceso es simple: tomar los puntos clave respecto a la situación dada, y a través de la falta de lógica, la erística, el relativismo moral, el simbolismo, la auto-contradicción, y la fantasía, enmarcan el discurso como uno en el que las mujeres pasan de la Opresión a la Liberación, pero en el que no llegarán allí sin la Lucha feminista.

Esto no significa que el feminismo opere de manera estática. El primer paso en el proceso que acabo de describir es actuar sobre los hechos de la vida real. Si las feministas no hicieran esto, su sermón no tendría ningún atractivo para el sector no-feminista, porque daría la impresión de no ser aplicable al mundo experiencial. El feminismo es anti-contextual en el sentido de que la narración se decide antes de los hechos, pero aún así depende del contexto de cualquier situación particular. El contexto de la vida real debe ser vivido y entendido, y sólo entonces podrá ser cooptado dentro del discurso feminista. Para dar un ejemplo claro, las feministas en Estados Unidos, hoy en día, no protestan por el derecho de las mujeres al voto. No lograrían nada si lo hicieran porque, teniendo ya el voto, no tienen a dónde más ir (en este aspecto). El sufragio no es un asunto relevante en el contexto del mundo real. Por otra parte, el hecho de que la mayoría de los líderes de negocios sean hombres puede ser verificado por la mayoría de la gente en el mundo; esto, entonces, se puede arrastrar hasta el discurso feminista como un ejemplo de Opresión.

Discúlpenme si soy demasiado simplista, pero se debe aclarar cómo el proceso de fabricación de la Lucha juega un papel crucial en la naturaleza cambiante de los derechos.

¿Qué es un derecho? Como se ha entendido típicamente, un derecho es una reivindicación que, en circunstancias usuales, es inviolable. En otras palabras, si yo tengo un derecho, entonces tengo una prerrogativa –el permiso para hacer algo que deseo hacer, o para ser protegido de algo que no deseo– y otros individuos no pueden quitarme dicha reivindicación. Un ejemplo claro sería que yo tengo el derecho a no ser atacado –no les está permitido a otros individuos atacarme. No obstante, puede que lo hagan, en cuyo caso habrán transgredido mi derecho; habrán hecho aquello que no les está permitido hacer, y me habrán impedido hacer (o evitar) aquellas cosas que se me está permitido hacer (o evitar). Por consiguiente, tengo la prerrogativa de buscar una recompensa por la violación de mi derecho.

Una teoría de derechos requiere un encargado de hacerlos cumplir, de tal manera que prevenga transgresiones a los derechos y otorgue recompensas a aquellos cuyos derechos han sido violados. El encargado con el cual ya estamos familiarizados es el estado, en particular aquellas instituciones involucradas en la creación y práctica de la ley: la legislatura, el poder judicial, la fuerza policiaca, etcétera. Es necesario que el estado posea el monopolio en el uso de la fuerza, pues de lo contrario no se lograría que se hicieran cumplir las reglas, y no habría un factor disuasorio en contra de las violaciones de derechos. En un caso extremo, los ciudadanos podrían rebelarse y tumbar un estado débil, y de manera subsecuente instituir su propia forma de justicia que podría no ser imparcial. Max Weber describió célebremente al estado como “el monopolio del uso legítimo de la fuerza”. Yo he dejado por fuera de mi definición la palabra “legítimo”, porque me parece un juicio totalmente subjetivo, sin mencionar inevitable, desde el punto de vista de aquellos que están en control del estado. Aquellos que toman el poder y lo usan para perseguir a un sector de la población, seguramente creerán que su monopolio en el uso de la fuerza es legítimo –sin duda, probablemente crean que su uso de la fuerza tiene más legitimidad que el del régimen que depusieron, sin importar cómo se haya comportado dicho régimen.

Es de notar que no hay un límite inherente al concepto de los derechos; no tiene un sistema de frenado. Nunca habrá un punto en el que podamos decir, “ahora tenemos todos los derechos”. Potencialmente, siempre habrá más derechos que los que podamos poseer, lo que no significa que debamos poseer más derechos. La posesión absoluta de todos los derechos concebibles sería una licencia inconcebible –autonomía total, en la que todas las reclamaciones serían permitidas. Esto significaría que el individuo con autorización estaría en la libertad de violar los derechos de los otros. En este caso, los derechos de otros serían insignificantes cada vez que se encuentren con el individuo con la autorización total. Lógicamente, no toda la gente puede tener posesión total de todos los derechos, debido a que a cada uno se le permitiría infringir los derechos de los demás –lo que implicaría que los derechos de nadie estarían seguros, y que el individuo o grupo más fuerte tendría derecho a establecer una regla arbitraria basada sólo en su fuerza física.

Es evidente que necesitamos limitaciones, y la Constitución de los Estados Unidos de América es un ejemplo en este aspecto. Como la mejor declaración de libertad personal y democracia representativa que el mundo haya conocido, existe para proteger una serie de derechos fundamentales de ser anulados por el grupo más fuerte de individuos –específicamente, el gobierno. Las leyes pueden ir y venir, pero mientras la constitución se mantenga, los derechos fundacionales del ciudadano individual son inmodificables –o, al menos, son extremadamente difíciles de remover o alterar. Donde sea que un gobierno viole repetidas veces su propia constitución, corre el riesgo (idóneamente, al menos) de ser derrocado por un levantamiento de sus ciudadanos, quienes formarían un colectivo más fuerte.

La Constitución de los Estados Unidos, adoptada en 1787, está construida sobre la filosofía liberal del tiempo, más especialmente la de John Locke. Algunas secciones de la Declaración de Independencia, firmada once años antes, son más o menos sacadas de su Segundo Tratado de Gobierno. Las ideas expresadas en esta obra no son las del liberalismo que conocemos hoy en día; son más próximas a los que ahora conocemos con el nombre de libertarismo. Fue solo en la segunda mitad del siglo XIX que el liberalismo experimentó una profunda transformación hacia una ideología colectivista con la que asociamos más fácilmente el término hoy en día.

En su texto de 1859, Sobre la Libertad, J. S. Mill introdujo una nueva articulación de la defensa moral liberal tradicional de los derechos individuales. Dice algo así como: los individuos tienen el derecho de hacer lo que escojan, mientras esto no lastime a otros. Mill ejercía precaución cuando consideraba la aplicación de este principio: uno no sería lastimado, por ejemplo, por perder en una competencia (ejemplo: el mercado libre). Siguiendo a Tocqueville, expresó su preocupación según la cual la democracia, si no se moderaba, podría resultar en una tiranía de la mayoría.

Podemos agradecer a los sucesores de Mill por pervertir el liberalismo individual y transformarlo en una filosofía colectivista y autoritaria. Sólo había un pequeño paso del axioma de Mill –los individuos tienen el derecho de hacer lo que escojan, siempre y cuando no lastimen a otros– a la doctrina del Nuevo Liberalismo: si no puedo hacer lo que de otra manera escogería, entonces alguien debe estar lastimándome. Fue el auto-proclamado “socialista liberal”, Leonard Trelawny Hobhouse, quien trabajó sobre las premisas de Mill y añadió un giro nuevo: que la libertad no es buena en sí misma, sino que deber subordinarse para un fin más alto. En consecuencia, cualquier libertad que no esté subordinada a este fin más alto, no está justificada moralmente. Fue el radical social Richard Henry Tawney quien, expandiendo esta idea, abogaba por una sociedad igualitaria, basado en la premisa según la cual “la libertad para el pez grande es la muerte de los peces pequeños” –en otras palabras, que ciertos grupos identificables no merecen la misma autonomía, sino que la suya debe ser restringida. Fue Lester Frank Ward quien repudió al individuo totalmente y arguyó que el estado debería dirigir todo desarrollo económico y social, incluyendo la felicidad de sus ciudadanos. Quizá lo más revelador de todo es que Ward era un entusiasta partidario de la noción según la cual las mujeres son innatamente superiores a los hombres. Para citar un pasaje especialmente relevante:

Y ahora desde el punto de vista del desarrollo intelectual mismo la encontramos lado a lado, y hombro a hombro con él, suministrando, desde el comienzo, allá en los tiempo prehistóricos, pre-sociales, e incluso pre-humanos, el complemente necesario para su carrera unilateral, apresurada, y obstinada, sin el cual él habría torcido y distorsionado la raza y la habría vuelto incapaz del progreso mismo que él declara inspirar exclusivamente. Y por esta razón, nuevamente, aun en el ámbito del intelecto, donde él reinaba supremo de buen grado, ella ha probado ser su igual y tiene derecho a parte del crédito que se añada al progreso humano conseguido hasta ahora.

El propósito de haberme desviado hacia la naturaleza cambiante de los derechos era para podernos concentrar en el desarrollo histórico que precipitó ciertos aspectos del feminismo moderno. Algunos colaboradores del Movimiento de Derechos de los Hombres han atacado la “modernidad” y los “valores de la Ilustración” de una manera algo abstracta. Esto está bien si tienen la intención de atacar la autonomía individual en general, pero debemos mirar detenidamente si realmente queremos llegar a la raíz de los problemas que los hombres deben enfrentar, como hombres, hoy en día –lo que resultaría, en mi opinión, en la privación de la autonomía masculina. Es la modernidad, y particularmente el pensamiento de la Ilustración, la que ha hecho posible la autonomía individual –y es el liberalismo social, y más específicamente el feminismo, el que la está volviendo imposible para los hombres.

La innovación del liberalismo social es evidente en la sección de la cita de Ward de más arriba en la que ya he hecho énfasis. Es exigir el derecho a algo; la creación de nuevas obligaciones que otros deben cumplir; la concepción de los derechos de las reivindicaciones, no de individuos, que deben ser iguales, pero en contra de un segmento identificado de la población (el grupo “enemigo”). Desde luego, cada derecho, si ha de ser tomado seriamente, exige obligaciones de parte de los otros –si yo tengo el derecho a no ser atacado, entonces usted no debe atacarme, y viceversa. La diferencia entre dicha afirmación y las demandas del Nuevo Liberalismo es que la primera es una obligación a la inacción, mientras que la última es una obligación a actuar. Mis obligaciones a la inacción significan que no puedo transgredir ciertos límites –los derechos de otras personas. No puedo lastimarlos, ni robarles, ni dañarles sus posesiones. Se me tiene prohibido hacer ciertas cosas que podrían interferir con la autonomía de otros, pero aparte de eso, puedo hacer lo que quiera. Las obligaciones a actuar son de una clase muy diferente: aquel que pueda forzarme a una obligación de ese tipo tiene el poder de darme órdenes. Me dirá cómo actuar, y yo no puedo actuar de ninguna otra manera, lo que restringe mi autonomía.

Por ejemplo, si usted requiere algún objeto para poder llevar a cabo algún proyecto, entonces su autonomía está restringida hasta que no posea dicho objeto. Por lo tanto, usted tiene el derecho a reclamar mi objeto, presumiendo que yo posea uno así. No importa si yo me he ganado dicho objeto o si lo poseo de manera legítima; la teoría dice que usted puede tener el objeto de todas maneras. Las reclamaciones sobre el derecho de propiedad están subordinadas a la autonomía de los individuos, es decir a los deseos (no las necesidades) de un grupo especialmente identificado como “víctimas”. Si, por ejemplo, yo estoy entrevistando a un hombre y a una mujer para un puesto en mi compañía, y la mujer exige que se le dé a ella el empleo puesto que es un paso crucial en su plan de carrera, le estoy negando su autonomía si no la contrato a ella, incluso si no es la candidata más calificada. Ella necesita el puesto para poder lograr aquello que en últimas quiere, y por lo tanto se le perjudica si no lo consigue. La doctrina del Nuevo Liberalismo –si yo no puedo hacer lo que elijo entonces alguien me debe estar haciendo daño– evidentemente sirve a los fines de víctima del feminismo. Cualquier límite impuesto a las acciones de las mujeres, incluyendo aquel que se establece en nombre de la equidad y la imparcialidad, puede ser tomado como la nueva Opresión, de acuerdo a esta doctrina.

El “Nuevo” Liberalismo, o liberalismo “social”, es de hecho una perversión y una corrupción del liberalismo –y encuentra su mayor expresión en el sistema de castas de derechos que las feministas están ocupadas creando. Los derechos de la mujeres, un eslogan pegajoso alguna vez proclamado como la marcha progresiva hacia un futuro más justo, se ha convertido en el as bajo la manga que nunca pierde su valor, listo para ser jugado en cualquier momento en que una mujer quiera “ganarle una a los muchachos”. En los primeros días, la idea de la Lucha era más creíble, e incluso parecía admirable en retrospectiva. Las mujeres luchaban por los derechos que los hombres poseían: el derecho al voto, el derecho a poseer propiedades, el derecho al divorcio, el derecho a tener el mismo salario que un hombre por el mismo trabajo. Había una vez en que era perfectamente plausible, para un observador imparcial, que el feminismo significara llegar a la igualdad entre los sexos. Esto no quiere decir que dicha perspectiva sea inherentemente correcta, sólo que es creíble, desde un punto de vista externo al feminismo, que dicha ideología tuviera en mente esa meta tan altruista.

¿Pero cuáles son los derechos de las mujeres por los que se aboga hoy en día? El derecho a confiscar el dinero de los hombres, el derecho a cometer alienación paternal, el derecho a cometer fraude de paternidad, el derecho a ganar el mismo salario por hacer menos trabajo, el derecho a pagar menos impuestos, el derecho a mutilar hombres, el derecho a confiscar esperma, el derecho a asesinar niños, el derecho a que nadie puede estar en desacuerdo con ellas, el derecho a la elección reproductiva, y el derecho a tomar esa decisión por los hombres también. En una interesante paradoja legal, algunas han incluso abogado –con éxito– para que las mujeres tengan el derecho a no ser castigadas por crímenes en lo absoluto. El resultado eventual de esto es un tipo de feudalismo sexual, en el que las mujeres gobiernan arbitrariamente, y en el que los hombres son mantenidos en sumisión, con menos derechos y más obligaciones. Hasta la fecha, la transformación de derechos en obligaciones a actuar nos ha ocasionado un estado de bienestar en el que, de acuerdo a The Futurist,

Virtualmente todos los gastos del gobierno […] desde Medicare hasta Obamacare, los subsidios de bienestar, los empleos en el sector público para mujeres, y la expansión de la población en prisión, son una transferencia neta de riqueza de los hombres a las mujeres, o un subproducto de la destrucción del Matrimonio 1.0. En cualquier caso, el “feminismo” es la causa […] Recordemos que las ganancias de los hombres pagan el 70%-80% de la totalidad de los impuestos.

El feminismo ve la independencia de los ciudadanos individuales como una barrera, no como una medida protectora. La autonomía personal obstaculiza el progreso del feminismo en moralizar al mundo y en desangrar a los hombres para el beneficio de las mujeres.

¿Derechos de las mujeres? Todo eso no es más que un intento de usurpar el poder.

Adam.