By August Løvenskiolds, (expanding on an older article by Peter Wright)

MGTOW YouTube producer Turd Flinging Monkey (TFM) recently talked about his theory of how historical patriarchies (real ones, not the faux versions feminists are forever whining about) interact with gynocentrism to produce cycles of societal growth and collapse. The theory, referred to as the traditionalism cycle, has appeared in major civilizations. The traditionalism cycle goes something like this:

- Patriarchal traditionalism ?

- Gynocentric traditionalism ?

- Progressive gynocentrism ?

- Societal collapse ?

- Return to step 1 above.

Here’s the video that describes this in more detail.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vKySNyUWxDA

The “traditionalism theory” is both descriptive of observed historical patterns and makes falsifiable predictions about how wealthy societies will break down over time if they fail to control gynocentric resource demands.

The theory is interesting on paper, though more unrealistic in practice for being too mechanistic and tidy; i.e., he proposes that societies start out as patriarchally controlled, then move through traditional and progressive forms of gynocentrism before collapsing under their own weight. The theory says that gynocentrism escalates with the advent of abundance (if and when abundance exists in a given culture).

What we appreciate about TFM’s exposition of his theory is that he did some detailed historical research to back it up – something sorely lacking in the discussion of the roots of gynocentrism. Instead of real research we often see pull-it-out-of-your-ass histories or dismissive appeals to biology – “it’s all in the genes.”

The irony that “Turd Flinging Monkey” did NOT pull it out of his ass is not lost on us.

The pull-it-out-of-your-ass kind of history is based on half-guesses, ideology and assumptions with little to no evidence – except perhaps references to items like Lysistrata, a play; Helen of Troy, a myth; The “Rule of Thumb” law authorizing standards of domestic violence (which even feminists admit is a complete fabrication), religious tales, fairy tales, and other fantasy sources – i.e. to assume myths and fables mirror real life has marginal utility at best and is often times just crap: have you ever seen a centaur?

Surely the classical depictions of centaurs must have mirrored real creatures and behaviors or they wouldn’t have mentioned it?! Any thinking person will recognize the problem; relying on ancient mythologies is akin to having future zoologists base the history of equine evolution on episodes of My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic.

Mythology’s chief value is in metaphor: when the goddess Ishtar’s love interest Gilgamesh spurns her, she threatens to unleash zombies unless her father punishes Gilgamesh for his impudence. The metaphors seem to boil out of this, the oldest of human stories:

- Women exercise covert, rather than overt, power.

- Spurned women will unleash their fury on the men who spurned them, as well as others.

- Fathers will side with angry, abusive daughters over innocent men.

- Women in power will give power to the dangerous and unproductive.

- Zombies are real!

Some of those metaphors are useful; some not so much.

The same goes for reductive biological explanations. Aside from the laziness of such approaches, the error in over-emphasizing biology is that biology is a product of environmental pressures that can, and do, change over time. Where you see biology you will always see a facilitating environment shaping it. Changes in environmental conditions (like over-population and resource depletion) could eliminate the biological “need” for gynocentrism entirely – wombs lose value when reducing the population is the only viable survival option for a species.

Fortunately, TFM breaks with the catalogue of errors and is trying to keep it fact based and real, even if he falls short by relying on an overly naïve, clockwork model that doesn’t speak to the complexities of cultural metamorphosis.

With that said there are some major, unspoken nuances that should be added to the conversation. The first is that there are degrees of gynocentric culture in both its traditional and progressive forms. Gynocentric societies are not cookie-cutter one-size-fits-all. Like hurricane categories with wind strengths of one to five, gynocentric culture can be imagined in a similar way – as differing in reach and packing winds anywhere from dangerous to destructive to catastrophic.

Like hurricanes, which become more intense depending on a confluence of atmospheric pressure, temperature, humidity, and wind direction, likewise the intensity of a given gynocentric culture rests on multiple factors. TFM has named one of them in his video: abundance.

Abundance is a good start, one that, in isolation from other factors, can definitely lead to a (lets call it) ‘category one’ gynocentric culture. But as we add more contributing factors the gynocentrism gets more pervasive and more destructive – factors like

- male to female population ratio,

- aristocratic conventions influencing the masses,

- communication technologies,

- reproductive technologies,

- military campaigns,

- foreign threats,

- the strength and structure of cultural narratives perpetuating the sentiment,

- and so on.

As these and many other factors converge the strength of gynocentric culture grows potentially up to a ‘category five’ such as was born in the Middle Ages with the mother of all gynocentric cultures that has spanned over 800 yrs and been exported from Europe to the rest of the world.

Ours.

We don’t intend to give an exhaustive reply here but will end with a general comment about our present culture. At this point the gynocentric culture birthed in medieval Europe is unprecedented in the long path of history – it was only there, and then, that the combination of romantic chivalry and courtly love was born, along with a bunch of other contributing factors that made this gynocentric revolution the mother of them all. But there’s no doubt there have occurred smaller, less intense manifestations of gynocentric culture throughout history along the lines TFM suggests.

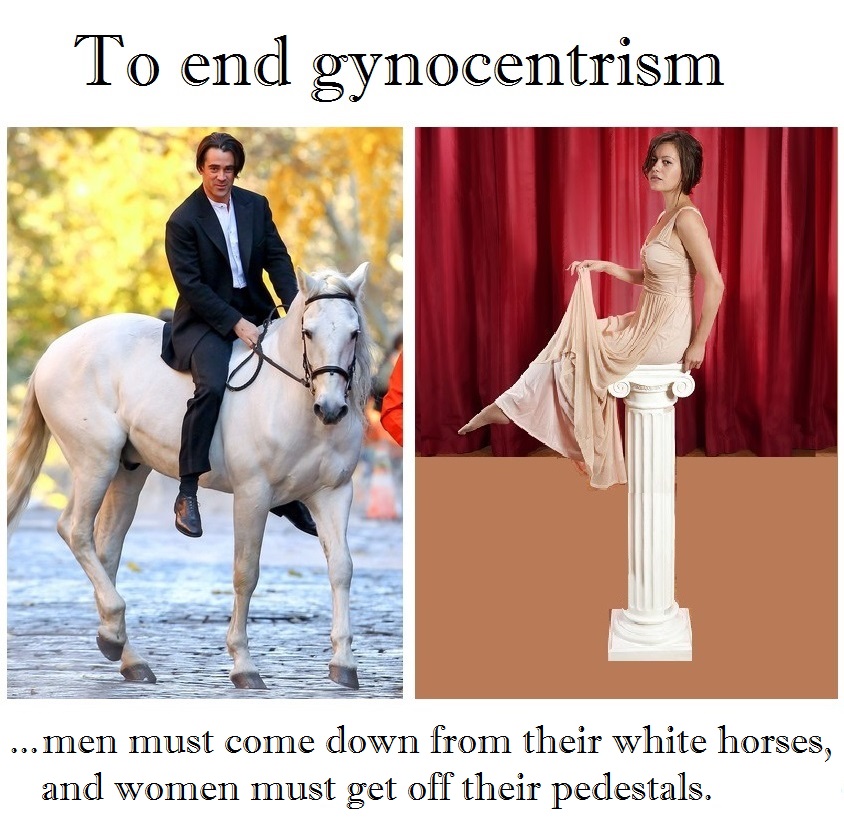

Recognizing gynocentrism and how it hurts men, families and society is critical to the process of limiting and perhaps undoing the toll that it takes on everyone.

An older version of this essay first appeared on gynocentrism.com.