The following audio presentation on the topic of storge (affection) was recorded in 1958 by the Episcopal Radio-TV Foundation in London.

Uncategorized

STORGE : an essay on affectionate love by C. S. Lewis

Editor’s introduction: The following essay on storge (affectionate love) by C. S. Lewis is from his book The Four Loves , published 1960. Lewis describes storge as a sentiment arising between people who have become familiar and intimate with each other, such as parents and children, or the affection that flows between husbands and wives. Lewis emphasizes that storge is a mammalian behaviour – that we humans are pairbonders, community bonders, and attachment-forming creatures. He wishes to differentiate it from agape (charitable love) with which storge otherwise has many similarities. “Like agape,” states Lewis, “storge is not puffed up, it suffers long and is kind, and loves the unlovable. It also loves goodness which is the ‘essentially lovable.'” 1

CHAPTER III

Affection

I begin with the humblest and most widely diffused of loves, the love in which our experience seems to differ least from that of the animals. Let me add at once that I do not on that account give it a lower value. Nothing in Man is either worse or better for being shared with the beasts. When we blame a man for being “a mere animal”, we mean not that he displays animal characteristics (we all do) but that he displays these, and only these, on occasions where the specifically human was demanded. (When we call him “brutal” we usually mean that he commits cruelties impossible to most real brutes; they’re not clever enough.)

The Greeks called this love storge (two syllables and the g is “hard”). I shall here call it simply Affection. My Greek Lexicon defines storge as “affection, especially of parents to offspring”; but also of offspring to parents. And that, I have no doubt, is the original form of the thing as well as the central meaning of the word. The image we must start with is that of a mother nursing a baby, a bitch or a cat with a basketful of puppies or kittens; all in a squeaking, nuzzling heap together; purrings, lickings, baby-talk, milk, warmth, the smell of young life.

The importance of this image is that it presents us at the very outset with a certain paradox. The Need and Need-love of the young is obvious; so is the Gift-love of the mother. She gives birth, gives suck, gives protection. On the other hand, she must give birth or die. She must give suck or suffer. That way, her Affection too is a Need-love. There is the paradox. It is a Need-love but what it needs is to give. It is a Gift-love but it needs to be needed. We shall have to return to this point.

But even in animal life, and still more in our own, Affection extends far beyond the relation of mother and young. This warm comfortableness, this satisfaction in being together, takes in all sorts of objects. It is indeed the least discriminating of loves. There are women for whom we can predict few wooers and men who are likely to have few friends. They have nothing to offer. But almost anyone can become an object of Affection; the ugly, the stupid, even the exasperating. There need be no apparent fitness between those whom it unites. I have seen it felt for an imbecile not only by his parents but by his brothers. It ignores the barriers of age, sex, class and education. It can exist between a clever young man from the university and an old nurse, though their minds inhabit different worlds. It ignores even the barriers of species. We see it not only between dog and man but, more surprisingly, between dog and cat. Gilbert White claims to have discovered it between a horse and a hen.

Some of the novelists have seized this well. In Tristram Shandy “my father” and Uncle Toby are so far from being united by any community of interests or ideas that they cannot converse for ten minutes without cross-purposes; but we are made to feel their deep mutual affection. So with Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, Pickwick and Sam Weller, Dick Swiveller and the Marchioness. So too, though probably without the author’s conscious intention, in The Wind in the Willows; the quaternion of Mole, Rat, Badger, and Toad suggests the amazing heterogeneity possible between those who are bound by Affection.

But Affection has its own criteria. Its objects have to be familiar. We can sometimes point to the very day and hour when we fell in love or began a new friendship. I doubt if we ever catch Affection beginning. To become aware of it is to become aware that it has already been going on for some time. The use of “old” or vieux as a term of Affection is significant. The dog barks at strangers who have never done it any harm and wags its tail for old acquaintances even if they never did it a good turn. The child will love a crusty old gardener who has hardly ever taken any notice of it and shrink from the visitor who is making every attempt to win its regard. But it must be an old gardener, one who has “always” been there–the short but seemingly immemorial “always” of childhood.

Affection, as I have said, is the humblest love. It gives itself no airs. People can be proud of being “in love”, or of friendship. Affection is modest–even furtive and shame-faced. Once when I had remarked on the affection quite often found between cat and dog, my friend replied, “Yes. But I bet no dog would ever confess it to the other dogs.” That is at least a good caricature of much human Affection. “Let homely faces stay at home,” says Comus. Now Affection has a very homely face. So have many of those for whom we feel it. It is no proof of our refinement or perceptiveness that we love them; nor that they love us. What I have called Appreciative Love is no basic element in Affection. It usually needs absence or bereavement to set us praising those to whom only Affection binds us. We take them for granted: and this taking for granted, which is an outrage in erotic love, is here right and proper up to a point. It fits the comfortable, quiet nature of the feeling. Affection would not be affection if it was loudly and frequently expressed; to produce it in public is like getting your household furniture out for a move. It did very well in its place, but it looks shabby or tawdry or grotesque in the sunshine. Affection almost slinks or seeps through our lives. It lives with humble, un-dress, private things; soft slippers, old clothes, old jokes, the thump of a sleepy dog’s tail on the kitchen floor, the sound of a sewing-machine, a gollywog left on the lawn.

But I must at once correct myself. I am talking of Affection as it is when it exists apart from the other loves. It often does so exist; often not. As gin is not only a drink in itself but also a base for many mixed drinks, so Affection, besides being a love itself, can enter into the other loves and colour them all through and become the very medium in which from day to day they operate. They would not perhaps wear very well without it. To make a friend is not the same as to become affectionate. But when your friend has become an old friend, all those things about him which had originally nothing to do with the friendship become familiar and dear with familiarity. As for erotic love, I can imagine nothing more disagreeable than to experience it for more than a very short time without this homespun clothing of affection. That would be a most uneasy condition, either too angelic or too animal or each by turn; never quite great enough or little enough for man. There is indeed a peculiar charm, both in friendship and in Eros, about those moments when Appreciative Love lies, as it were, curled up asleep, and the mere ease and ordinariness of the relationship (free as solitude, yet neither is alone) wraps us round. No need to talk. No need to make love. No needs at all except perhaps to stir the fire.

This blending and overlapping of the loves is well kept before us by the fact that at most times and places all three of them had in common, as their expression, the kiss. In modern England friendship no longer uses it, but Affection and Eros do. It belongs so fully to both that we cannot now tell which borrowed it from the other or whether there were borrowing at all. To be sure, you may say that the kiss of Affection differs from the kiss of Eros. Yes; but not all kisses between lovers are lovers’ kisses. Again, both these loves tend–and it embarrasses many moderns–to use a “little language” or “baby talk”. And this is not peculiar to the human species. Professor Lorenz has told us that when jackdaws are amorous their calls “consist chiefly of infantile sounds reserved by adult jackdaws for these occasions” (King Solomon’s Ring, p. 158). We and the birds have the same excuse. Different sorts of tenderness are both tenderness and the language of the earliest tenderness we have ever known is recalled to do duty for the new sort.

One of the most remarkable by-products of Affection has not yet been mentioned. I have said that is not primarily an Appreciative Love. It is not discriminating. It can “rub along” with the most unpromising people. Yet oddly enough this very fact means that it can in the end make appreciations possible which, but for it might never have existed. We may say, and not quite untruly, that we have chosen our friends and the woman we love for their various excellences–for beauty, frankness, goodness of heart, wit, intelligence, or what not. But it had to be the particular kind of wit, the particular kind of beauty, the particular kind of goodness that we like, and we have our personal tastes in these matters. That is why friends and lovers feel that they were “made for one another”. The especial glory of Affection is that it can unite those who most emphatically, even comically, are not; people who, if they had not found themselves put down by fate in the same household or community, would have had nothing to do with each other. If Affection grows out of this–of course it often does not–their eyes begin to open. Growing fond of “old so-and-so”, at first simply because he happens to be there, I presently begin to see that there is “something in him” after all. The moment when one first says, really meaning it, that though he is not “my sort of man” he is a very good man “in his own way” is one of liberation. It does not feel like that; we may feel only tolerant and indulgent. But really we have crossed a frontier. That “in his own way” means that we are getting beyond our own idiosyncracies, that we are learning to appreciate goodness or intelligence in themselves, not merely goodness or intelligence flavoured and served to suit our own palate.

“Dogs and cats should always be brought up together,” said someone, “it broadens their minds so.” Affection broadens ours; of all natural loves it is the most catholic, the least finical, the broadest. The people with whom you are thrown together in the family, the college, the mess, the ship, the religious house, are from this point of view a wider circle than the friends, however numerous, whom you have made for yourself in the outer world. By having a great many friends I do not prove that I have a wide appreciation of human excellence. You might as well say I prove the width of my literary taste by being able to enjoy all the books in my own study. The answer is the same in both cases–“You chose those books. You chose those friends. Of course they suit you.” The truly wide taste in reading is that which enables a man to find something for his needs on the sixpenny tray outside any secondhand bookshop. The truly wide taste in humanity will similarly find something to appreciate in the cross-section of humanity whom one has to meet every day. In my experience it is Affection that creates this taste, teaching us first to notice, then to endure, then to smile at, then to enjoy, and finally to appreciate, the people who “happen to be there”. Made for us? Thank God, no. They are themselves, odder than you could have believed and worth far more than we guessed.

And now we are drawing near the point of danger. Affection, I have said, gives itself no airs; charity, said St. Paul, is not puffed up. Affection can love the unattractive: God and His saints love the unlovable. Affection “does not expect too much”, turns a blind eye to faults, revives easily after quarrels; just so charity suffers long and is kind and forgives. Affection opens our eyes to goodness we could not have seen, or should not have appreciated without it. So does humble sanctity. If we dwelled exclusively on these resemblances we might be led on to believe that this Affection is not simply one of the natural loves but is Love Himself working in our human hearts and fulfilling the law. Were the Victorian novelists right after all? Is love (of this sort) really enough? Are the “domestic affections”, when in their best and fullest development, the same thing as the Christian life? The answer to all these questions, I submit, is certainly No.

I do not mean simply that those novelists sometimes wrote as if they had never heard the text about “hating” wife and mother and one’s own life also. That of course is true. The rivalry between all natural loves and the love of God is something a Christian dare not forget. God is the great Rival, the ultimate object of human jealousy; that beauty, terrible as the Gorgon’s, which may at any moment steal from me–or it seems like stealing to me–my wife’s or husband’s or daughter’s heart. The bitterness of some unbelief, though disguised even from those who feel it as anti-clericalism or hatred of superstition, is really due to this. But I am not at present thinking of that rivalry; we shall have to face it in a later chapter. For the moment our business is more “down to earth”.

How many of these “happy homes” really exist? Worse still; are all the unhappy ones unhappy because Affection is absent? I believe not. It can be present, causing the unhappiness. Nearly all the characteristics of this love are ambivalent. They may work for ill as well as for good. By itself, left simply to follow its own bent, it can darken and degrade human life. The debunkers and anti-sentimentalists have not said all the truth about it, but all they have said is true.

Symptomatic of this, perhaps, is the odiousness of nearly all those treacly tunes and saccharine poems in which popular art expresses Affection. They are odious because of their falsity. They represent as a ready-made recipe for bliss (and even for goodness) what is in fact only an opportunity. There is no hint that we shall have to do anything: only let Affection pour over us like a warm shower-bath and all, it is implied, will be well.

Affection, we have seen, includes both Need-love and Gift-love. I begin with the Need–our craving for the Affection of others.

Now there is a clear reason why this craving, of all love-cravings, easily becomes the most unreasonable. I have said that almost anyone may be the object of Affection. Yes; and almost everyone expects to be. The egregious Mr. Pontifex in The Way of all Flesh is outraged to discover that his son does not love him; it is “unnatural” for a boy not to love his own father. It never occurs to him to ask whether, since the first day the boy can remember, he has ever done or said anything that could excite love. Similarly, at the beginning of King Lear the hero is shown as a very unlovable old man devoured with a ravenous appetite for Affection. I am driven to literary examples because you, the reader, and I, do not live in the same neighbourhood; if we did, there would unfortunately be no difficulty about replacing them with examples from real life. The thing happens every day. And we can see why. We all know that we must do something, if not to merit, at least to attract, erotic love or friendship. But Affection is often assumed to be provided, ready made, by nature; “built-in”, “laid-on”, “on the house”. We have a right to expect it. If the others do not give it, they are “unnatural”.

This assumption is no doubt the distortion of a truth. Much has been “built-in”. Because we are a mammalian species, instinct will provide at least some degree, often a high one, of maternal love. Because we are a social species familiar association provides a milieu in which, if all goes well, Affection will arise and grow strong without demanding any very shining qualities in its objects. If it is given us it will not necessarily be given us on our merits; we may get it with very little trouble. From a dim perception of the truth (many are loved with Affection far beyond their deserts) Mr. Pontifex draws the ludicrous conclusion, “Therefore I, without desert, have a right to it.” It is as if, on a far higher plane, we argued that because no man by merit has a right to the Grace of God, I, having no merit, am entitled to it. There is no question or rights in either case. What we have is not “a right to expect” but a “reasonable expectation” of being loved by our intimates if we, and they, are more or less ordinary people. But we may not be. We may be intolerable. If we are, “nature” will work against us. For the very same conditions of intimacy which make Affection possible also–and no less naturally–make possible a peculiarly incurable distaste; a hatred as immemorial, constant, unemphatic, almost at times unconscious, as the corresponding form of love. Siegfried, in the opera, could not remember a time before every shuffle, mutter, and fidget of his dwarfish foster-father had become odious. We never catch this kind of hatred, any more than Affection, at the moment of its beginning. It was always there before. Notice that old is a term of wearied loathing as well as of endearment: “at his old tricks,” “in his old way,” “the same old thing.”

It would be absurd to say that Lear is lacking in Affection. In so far as Affection is Need-love he is half-crazy with it. Unless, in his own way, he loved his daughters he would not so desperately desire their love. The most unlovable parent (or child) may be full of such ravenous love. But it works to their own misery and everyone else’s. The situation becomes suffocating. If people are already unlovable a continual demand on their part (as of right) to be loved–their manifest sense of injury, their reproaches, whether loud and clamorous or merely implicit in every look and gesture of resentful self-pity–produce in us a sense of guilt (they are intended to do so) for a fault we could not have avoided and cannot cease to commit. They seal up the very fountain for which they are thirsty. If ever, at some favoured moment, any germ of Affection for them stirs in us, their demand for more and still more, petrifies us again. And of course such people always desire the same proof of our love; we are to join their side, to hear and share their grievance against someone else. If my boy really loved me he would see how selfish his father is … if my brother loved me he would make a party with me against my sister … if you loved me you wouldn’t let me be treated like this …

And all the while they remain unaware of the real road. “If you would be loved, be lovable,” said Ovid. That cheery old reprobate only meant, “If you want to attract the girls you must be attractive,” but his maxim has a wider application. The amorist was wiser in his generation than Mr. Pontifex and King Lear.

The really surprising thing is not that these insatiable demands made by the unlovable are sometimes made in vain, but that they are so often met. Sometimes one sees a woman’s girlhood, youth and long years of her maturity up to the verge of old age all spent in tending, obeying, caressing, and perhaps supporting, a maternal vampire who can never be caressed and obeyed enough. The sacrifice–but there are two opinions about that–may be beautiful; the old woman who exacts it is not.

The “built-in” or unmerited character of Affection thus invites a hideous misinterpretation. So does its ease and informality.

We hear a great deal about the rudeness of the rising generation. I am an oldster myself and might be expected to take the oldsters’ side, but in fact I have been far more impressed by the bad manners of parents to children than by those of children to parents. Who has not been the embarrassed guest at family meals where the father or mother treated their grown-up offspring with an incivility which, offered to any other young people, would simply have terminated the acquaintance? Dogmatic assertions on matters which the children understand and their elders don’t, ruthless interruptions, flat contradictions, ridicule of things the young take seriously–sometimes of their religion–insulting references to their friends, all provide an easy answer to the question “Why are they always out? Why do they like every house better than their home?” Who does not prefer civility to barbarism?

If you asked any of these insufferable people–they are not all parents of course–why they behaved that way at home, they would reply, “Oh, hang it all, one comes home to relax. A chap can’t be always on his best behaviour. If a man can’t be himself in his own house, where can he? Of course we don’t want Company Manners at home. We’re a happy family. We can say anything to one another here. No one minds. We all understand.”

Once again it is so nearly true yet so fatally wrong. Affection is an affair of old clothes, and ease, of the unguarded moment, of liberties which would be ill-bred if we took them with strangers. But old clothes are one thing; to wear the same shirt till it stank would be another. There are proper clothes for a garden party; but the clothes for home must be proper too, in their own different way. Similarly there is a distinction between public and domestic courtesy. The root principle of both is the same: “that no one give any kind of preference to himself.” But the more public the occasion, the more our obedience to this principle has been “taped” or formalised. There are “rules” of good manners. The more intimate the occasion, the less the formalisation; but not therefore the less need of courtesy. On the contrary, Affection at its best practises a courtesy which is incomparably more subtle, sensitive, and deep than the public kind. In public a ritual would do. At home you must have the reality which that ritual represented, or else the deafening triumphs of the greatest egoist present. You must really give no kind of preference to yourself; at a party it is enough to conceal the preference. Hence the old proverb “come live with me and you’ll know me”. Hence a man’s familiar manners first reveal the true value of his (significantly odious phrase!) “Company” or “Party” manners. Those who leave their manners behind them when they come home from the dance or the sherry party have no real courtesy even there. They were merely aping those who had.

“We can say anything to one another.” The truth behind this is that Affection at its best can say whatever Affection at its best wishes to say, regardless of the rules that govern public courtesy; for Affection at its best wishes neither to wound nor to humiliate nor to domineer. You may address the wife of your bosom as “Pig!” when she has inadvertently drunk your cocktail as well as her own. You may roar down the story which your father is telling once too often. You may tease and hoax and banter. You can say “Shut up. I want to read”. You can do anything in the right tone and at the right moment–the tone and moment which are not intended to, and will not, hurt. The better the Affection the more unerringly it knows which these are (every love has its art of love). But the domestic Rudesby means something quite different when he claims liberty to say “anything”. Having a very imperfect sort of Affection himself, or perhaps at that moment none, he arrogates to himself the beautiful liberties which only the fullest Affection has a right to or knows how to manage. He then uses them spitefully in obedience to his resentments; or ruthlessly in obedience to his egoism; or at best stupidly, lacking the art. And all the time he may have a clear conscience. He knows that Affection takes liberties. He is taking liberties. Therefore (he concludes) he is being affectionate. Resent anything and he will say that the defect of love is on your side. He is hurt. He has been misunderstood.

He then sometimes avenges himself by getting on his high horse and becoming elaborately “polite”. The implication is of course, “Oh! So we are not to be intimate? We are to behave like mere acquaintances? I had hoped–but no matter. Have it your own way.” This illustrates prettily the difference between intimate and formal courtesy. Precisely what suits the one may be a breach of the other. To be free and easy when you are presented to some eminent stranger is bad manners; to practice formal and ceremonial courtesies at home (“public faces in private places”) is–and is always intended to be–bad manners. There is a delicious illustration of really good domestic manners in Tristram Shandy. At a singularly unsuitable moment Uncle Toby has been holding forth on his favourite theme of fortification. “My Father,” driven for once beyond endurance, violently interrupts. Then he sees his brother’s face; the utterly unretaliating face of Toby, deeply wounded, not by the slight to himself–he would never think of that–but by the slight to the noble art. My Father at once repents. There is an apology, a total reconciliation. Uncle Toby, to show how complete is his forgiveness, to show that he is not on his dignity, resumes the lecture on fortification.

But we have not yet touched on jealousy. I suppose no one now believes that jealousy is especially connected with erotic love. If anyone does the behaviour of children, employees, and domestic animals, ought soon to undeceive him. Every kind of love, almost every kind of association, is liable to it. The jealousy of Affection is closely connected with its reliance on what is old and familiar. So also with the total, or relative, unimportance for Affection of what I call Appreciative love. We don’t want the “old, familiar faces” to become brighter or more beautiful, the old ways to be changed even for the better, the old jokes and interests to be replaced by exciting novelties. Change is a threat to Affection.

A brother and sister, or two brothers–for sex here is not at work–grow to a certain age sharing everything. They have read the same comics, climbed the same trees, been pirates or spacemen together, taken up and abandoned stamp-collecting at the same moment. Then a dreadful thing happens. One of them flashes ahead–discovers poetry or science or serious music or perhaps undergoes a religious conversion. His life is flooded with the new interest. The other cannot share it; he is left behind. I doubt whether even the infidelity of a wife or husband raises a more miserable sense of desertion or a fiercer jealousy than this can sometimes do. It is not yet jealousy of the new friends whom the deserter will soon be making. That will come; at first it is jealousy of the thing itself–of this science, this music, of God (always called “religion” or “all this religion” in such contexts). The jealousy will probably be expressed by ridicule. The new interest is “all silly nonsense”, contemptibly childish (or contemptibly grown-up), or else the deserter is not really interested in it at all–he’s showing off, swanking; it’s all affectation. Presently the books will be hidden, the scientific specimens destroyed, the radio forcibly switched off the classical programmes. For Affection is the most instinctive, in that sense the most animal, of the loves; its jealousy is proportionately fierce. It snarls and bares its teeth like a dog whose food has been snatched away. And why would it not? Something or someone has snatched away from the child I am picturing his life-long food, his second self. His world is in ruins.

But it is not only children who react thus. Few things in the ordinary peacetime life of a civilised country are more nearly fiendish than the rancour with which a whole unbelieving family will turn on the one member of it who has become a Christian, or a whole lowbrow family on the one who shows signs of becoming an intellectual. This is not, as I once thought, simply the innate and, as it were, disinterested hatred of darkness for light. A church-going family in which one has gone atheist will not always behave any better. It is the reaction to a desertion, even to robbery. Someone or something has stolen “our” boy (or girl). He who was one of Us has become one of Them. What right had anybody to do it? He is ours. But once change has thus begun, who knows where it will end? (And we all so happy and comfortable before and doing no harm to no one!)

Sometimes a curious double jealousy is felt, or rather two inconsistent jealousies which chase each other round in the sufferer’s mind. On the other hand “This” is “All nonsense, all bloody high-brow nonsense, all canting humbug”. But on the other, “Supposing–it can’t be, it mustn’t be, but just supposing–there were something in it?” Supposing there really were anything in literature, or in Christianity? How if the deserter has really entered a new world which the rest of us never suspected? But, if so, how unfair! Why him? Why was it never opened to us? “A chit of a girl–a whipper-snapper of a boy–being shown things that are hidden from their elders?” And since that is clearly incredible and unendurable, jealousy returns to the hypothesis “All nonsense”.

Parents in this state are much more comfortably placed than brothers and sisters. Their past is unknown to their children. Whatever the deserter’s new world is, they can always claim that they have been through it themselves and come out the other end. “It’s a phase,” they say, “It’ll blow over.” Nothing could be more satisfactory. It cannot be there and then refuted, for it is a statement about the future. It stings, yet–so indulgently said–is hard to resent. Better still, the elders may really believe it. Best of all, it may finally turn out to have been true. It won’t be their fault if it doesn’t.

“Boy, boy, these wild courses of yours will break your mother’s heart.” That eminently Victorian appeal may often have been true. Affection was bitterly wounded when one member of the family fell from the homely ethos into something worse–gambling, drink, keeping an opera girl. Unfortunately it is almost equally possible to break your mother’s heart by rising above the homely ethos. The conservative tenacity of Affection works both ways. It can be a domestic counterpart to that nationally suicidal type of education which keeps back the promising child because the idlers and dunces might be “hurt” if it were undemocratically moved into a higher class than themselves.

All these perversions of Affection are mainly connected with Affection as a Need-love. But Affection as a Gift-love has its perversions too.

I am thinking of Mrs. Fidget, who died a few months ago. It is really astonishing how her family have brightened up. The drawn look has gone from her husband’s face; he begins to be able to laugh. The younger boy, whom I had always thought an embittered, peevish little creature, turns out to be quite human. The elder, who was hardly ever at home except when he was in bed, is nearly always there now and has begun to reorganise the garden. The girl, who was always supposed to be “delicate” (though I never found out what exactly the trouble was), now has the riding lessons which were once out of the question, dances all night, and plays any amount of tennis. Even the dog who was never allowed out except on a lead is now a well-known member of the Lamp-post Club in their road.

Mrs. Fidget very often said that she lived for her family. And it was not untrue. Everyone in the neighbourhood knew it. “She lives for her family,” they said; “what a wife and mother!” She did all the washing; true, she did it badly, and they could have afforded to send it out to a laundry, and they frequently begged her not to do it. But she did. There was always a hot lunch for anyone who was at home and always a hot meal at night (even in midsummer). They implored her not to provide this. They protested almost with tears in their eyes (and with truth) that they liked cold meals. It made no difference. She was living for her family. She always sat up to “welcome” you home if you were out late at night; two or three in the morning, it made no odds; you would always find the frail, pale, weary face awaiting you, like a silent accusation. Which meant of course that you couldn’t with any decency go out very often. She was always making things too; being in her own estimation (I’m no judge myself) an excellent amateur dressmaker and a great knitter. And of course, unless you were a heartless brute, you had to wear the things. (The Vicar tells me that, since her death, the contributions of that family alone to “sales of work” outweigh those of all his other parishioners put together). And then her care for their health! She bore the whole burden of that daughter’s “delicacy” alone. The Doctor–an old friend, and it was not being done on National Health–was never allowed to discuss matters with his patient. After the briefest examination of her, he was taken into another room by the mother. The girl was to have no worries, no responsibility for her own health. Only loving care; caresses, special foods, horrible tonic wines, and breakfast in bed. For Mrs. Fidget, as she so often said, would “work her fingers to the bone” for her family. They couldn’t stop her. Nor could they–being decent people–quite sit still and watch her do it. They had to help. Indeed they were always having to help. That is, they did things for her to help her to do things for them which they didn’t want done. As for the dear dog, it was to her, she said, “just like one of the children.” It was in fact as like one of them as she could make it. But since it had no scruples it got on rather better than they, and though vetted, dieted and guarded within an inch of its life, contrived sometimes to reach the dustbin or the dog next door.

The Vicar says Mrs. Fidget is now at rest. Let us hope she is. What’s quite certain is that her family are.

It is easy to see how liability to this state is, so to speak, congenital in the maternal instinct. This, as we saw, is a Gift-love, but one that needs to give; therefore needs to be needed. But the proper aim of giving is to put the recipient in a state where he no longer needs our gift. We feed children in order that they may soon be able to feed themselves; we teach them in order that they may soon not need our teaching. Thus a heavy task is laid upon this Gift-love. It must work towards its own abdication. We must aim at making ourselves superfluous. The hour when we can say “They need me no longer” should be our reward. But the instinct, simply in its own nature, has no power to fulfil this law. The instinct desires the good of its object, but not simply; only the good it can itself give. A much higher love–a love which desires the good of the object as such, from whatever source that good comes–must step in and help or tame the instinct before it can make the abdication. And of course it often does. But where it does not, the ravenous need to be needed will gratify itself either by keeping its objects needy or by inventing for them imaginary needs. It will do this all the more ruthlessly because it thinks (in one sense truly) that it is a Gift-love and therefore regards itself as “unselfish”.

It is not only mothers who can do this. All those other Affections which, whether by derivation from parental instinct or by similarity of function, need to be needed may fall into the same pit. The Affection of patron for protégé is one. In Jane Austen’s novel, Emma intends that Harriet Smith should have a happy life; but only the sort of happy life which Emma herself has planned for her. My own profession–that of a university teacher–is in this way dangerous. If we are any good we must always be working towards the moment at which our pupils are fit to become our critics and rivals. We should be delighted when it arrives, as the fencing master is delighted when his pupil can pink and disarm him. And many are.

But not all. I am old enough to remember the sad case of Dr. Quartz. No university boasted a more effective or devoted teacher. He spent the whole of himself on his pupils. He made an indelible impression on nearly all of them. He was the object of much well merited hero-worship. Naturally, and delightfully, they continued to visit him after the tutorial relation had ended–went round to his house of an evening and had famous discussions. But the curious thing is that this never lasted. Sooner or later–it might be within a few months or even a few weeks–came the fatal evening when they knocked on his door and were told that the Doctor was engaged. After that he would always be engaged. They were banished from him forever. This was because, at their last meeting, they had rebelled. They had asserted their independence–differed from the master and supported their own view, perhaps not without success. Faced with that very independence which he had laboured to produce and which it was his duty to produce if he could, Dr. Quartz could not bear it. Wotan had toiled to create the free Siegfried; presented with the free Siegfried, he was enraged. Dr. Quartz was an unhappy man.

This terrible need to be needed often finds its outlet in pampering an animal. To learn that someone is “fond of animals” tells us very little until we know in what way. For there are two ways. On the one hand the higher and domesticated animal is, so to speak, a “bridge” between us and the rest of nature. We all at times feel somewhat painfully our human isolation from the sub-human world–the atrophy of instinct which our intelligence entails, our excessive self-consciousness, the innumerable complexities of our situation, our inability to live in the present. If only we could shuffle it all off! We must not–and incidentally we can’t–become beasts. But we can be with a beast. It is personal enough to give the word with a real meaning; yet it remains very largely an unconscious little bundle of biological impulses. It has three legs in nature’s world and one in ours. It is a link, an ambassador. Who would not wish, as Bosanquet put it, “to have a representative at the court of Pan”? Man with dog closes a gap in the universe. But of course animals are often used in a worse fashion. If you need to be needed and if your family, very properly, decline to need you, a pet is the obvious substitute. You can keep it all its life in need of you. You can keep it permanently infantile, reduce it to permanent invalidism, cut it off from all genuine animal well-being, and compensate for this by creating needs for countless little indulgences which only you can grant. The unfortunate creature thus becomes very useful to the rest of the household; it acts as a sump or drain–you are too busy spoiling a dog’s life to spoil theirs. Dogs are better for this purpose than cats: a monkey, I am told, is best of all. Also it is more like the real thing. To be sure, it’s all very bad luck for the animal. But probably it cannot fully realise the wrong you have done it. Better still, you would never know if it did. The most down-trodden human, driven too far, may one day turn and blurt out a terrible truth. Animals can’t speak.

Those who say “The more I see of men the better I like dogs”–those who find in animals a relief from the demands of human companionship–will be well advised to examine their real reasons.

I hope I am not being misunderstood. If this chapter leads anyone to doubt that the lack of “natural affection” is an extreme depravity I shall have failed. Nor do I question for a moment that Affection is responsible for nine-tenths of whatever solid and durable happiness there is in our natural lives. I shall therefore have some sympathy with those whose comment on the last few pages takes the form “Of course. Of course. These things do happen. Selfish or neurotic people can twist anything, even love, into some sort of misery or exploitation. But why stress these marginal cases? A little common sense, a little give and take, prevents their occurrence among decent people.” But I think this comment itself needs a commentary.

Firstly, as to neurotic. I do not think we shall see things more clearly by classifying all these malefical states of Affection as pathological. No doubt there are really pathological conditions which make the temptation to these states abnormally hard or even impossible to resist for particular people. Send those people to the doctors by all means. But I believe that everyone who is honest with himself will admit that he has felt these temptations. Their occurrence is not a disease; or if it is, the name of that disease is Being a Fallen Man. In ordinary people the yielding to them–and who does not sometimes yield?–is not disease, but sin. Spiritual direction will here help us more than medical treatment. Medicine labours to restore “natural” structure or “normal” function. But greed, egoism, self-deception and self-pity are not unnatural or abnormal in the same sense as astigmatism or a floating kidney. For who, in Heaven’s name, would describe as natural or normal the man from whom these failings were wholly absent? “Natural”, if you like, in a quite different sense; archnatural, unfallen. We have seen only one such Man. And He was not at all like the psychologist’s picture of the integrated, balanced, adjusted, happily married, employed, popular citizen. You can’t really be very well “adjusted” to your world if it says you “have a devil” and ends by nailing you up naked to a stake of wood.

But secondly, the comment in its own language admits the very thing I am trying to say. Affection produces happiness if–and only if–there is common sense and give and take and “decency”. In other words, only if something more, and other, than Affection is added. The mere feeling is not enough. You need “common sense”, that is, reason. You need “give and take”; that is, you need justice, continually stimulating mere Affection when it fades and restraining it when it forgets or would defy the art of love. You need “decency”. There is no disguising the fact that this means goodness; patience, self-denial, humility, and the continual intervention of a far higher sort of love than Affection, in itself, can ever be. That is the whole point. If we try to live by Affection alone, Affection will “go bad on us”.

How bad, I believe we seldom recognise. Can Mrs. Fidget really have been quite unaware of the countless frustrations and miseries she inflicted on her family? It passes belief. She knew–of course she knew–that it spoiled your whole evening to know that when you came home you would find her uselessly, accusingly, “sitting up for you”. She continued all these practices because if she had dropped them she would have been faced with the fact she was determined not to see; would have known that she was not necessary. That is the first motive. Then too, the very laboriousness of her life silenced her secret doubts as to the quality of her love. The more her feet burned and her back ached, the better, for this pain whispered in her ear “How much I must love them if I do all this!” That is the second motive. But I think there is a lower depth. The unappreciativeness of the others, those terrible, wounding words–anything will “wound” a Mrs. Fidget–in which they begged her to send the washing out, enabled her to feel ill-used, therefore, to have a continual grievance, to enjoy the pleasures of resentment. If anyone says he does not know those pleasures, he is a liar or a saint. It is true that they are pleasures only to those who hate. But then a love like Mrs. Fidget’s contains a good deal of hatred. It was of erotic love that the Roman poet said, “I love and hate,” but other kinds of love admit the same mixture. They carry in them the seeds of hatred. If Affection is made the absolute sovereign of a human life the seeds will germinate. Love, having become a god, becomes a demon.

Which Greek love is synonymous with pairbonding? – Storge

I asked the following question of five AI machines: Which Greek love is considered synonymous with pairbonding?

ANSWERS:

1. BING COPILOT:

In the context of pairbonding, the Greek word “Storge” is particularly relevant. Let’s explore it further:

- Storge:

- Meaning: Storge refers to devoted love and is often associated with familial bonds.

- Application: It describes the affection and care within families, especially between parents and children.

- One-Sided: While it can be mutual, it may also be one-sided, such as a parent’s love for their child.

- Long-Term Fulfillment: Storge is not as intense as other forms of love, but it is fulfilling and enduring over time.

- Essential Component: In pairbonding relationships, Storge is vital alongside other forms of love, creating a strong and lasting bond.

- Plato’s View: The combination of Storge and Eros (sexual desire) leads to the highest form of love—a “friendship between lovers”1.

So, when thinking about pairbonding, consider Storge—the devoted, caring love that forms the foundation for lasting connections.

2. GAB AI:

Storge, which is familial love, is often considered synonymous with pairbonding. This love is characterized by deep affection and familiarity, such as the love between parents and children, or close friends. It is a natural, unconditional love that develops over time through shared experiences and emotional bonds.

3. CHAT GPT:

The Greek love that is synonymous with pairbonding is “storge.” Storge is often associated with familial love, particularly the affectionate bond between parents and children, but it can also refer to the deep, steady affection that develops between partners or close friends over time. Storge is characterized by familiarity, loyalty, trust, commitment and mutual respect, making it closely tied to the idea of pairbonding or companionship, and the forming of lasting relationships.

4. AI CHATTING:

The Greek love concept that is considered synonymous with pairbonding is “storge.” Storge is an affectionate, familial type of love that is often associated with parent-child relationships or long-term friendships. It represents a deep bond and emotional attachment between individuals who have a strong sense of care and commitment towards each other.

5. YOU.COM:

The Greek love synonymous with pairbonding is storge. Storge refers to the love between family members and is characterized by a strong bond shared by parents, children, and those considered family. It is a protective love that can withstand hardships and trials. While the word storge doesn’t appear in the New Testament, the opposite form of storge is used twice in the New Testament, translated as “unloving” or “heartless.” It’s important to note that pair bonds are a biological phenomenon and are not equivalent to the human social institution of marriage, however marriage may be a consequence of pair bonding.

Sane alternatives to romantic love

Articles by Paul Elam:

– Arranged Marriages and the Rise of Romantic Love (2016)

– For Real Love to Emerge, Romantic Love Must Die – Part 1 (2017)

– For Real Love to Emerge, Romantic Love Must Die – Part 2 (2017)

– For Real Love to Emerge, Romantic Love Must Die – Part 3 (2017)

Articles on Christian vs. Romantic love by Paul Elam:

– How We Conflated the Love of Christ With the Love of Women (2024)

– How Jesus Rejected the Worship of Women (2024)

– The Great Conflation: Romantic vs Christian Love (2024)

– Harlequin Jesus (2024)

Articles by Peter Wright:

– Sexualized Romantic Love, and Pairbonding (2013)

– Romantic Love Vs. Friendship (2013)

– Down The Aisle Again On The Marriage Question: Is It Relevant? (2015)

– A Short Word on Love Terminology (2023)

– Love in the Song of Songs (2024)

– Don’t confuse Eros (sexual desire) with Amor (romantic love) (2024)

– Christian Churches Conflate Romantic Love with Agape (2024)

– Romantic Love versus Family Love: Amore vs Storge (2024)

– Ancient Greek Kinds of Love (2025)

Other authors on the topic of family love (storge):

– Storge: Audio-recording of C.S. Lewis: Episcopal Radio-TV Foundation (1958)

– Storge: an essay on affectionate love by C. S. Lewis (1960)

– American & Asian Social Contract: Family Versus Romance – Alan Macfarlane (1986)

– A Storgic Love Paradigm, by Yuko Minowa & Russell W. Belk (2018)

– AI tells which Greek love is synonymous with pairbonding (2024)

– English language qualities associated with the Greek Storge (2024)

– Which features do storge and agape have in common? (2024)

– Family in Asia, versus family in the West (2024)

– The Root Meaning of Storge (family love) (2025)

– Storge Love as Pairbonding Love – Open AI (2025)

Romantic love versus family love (Amore vs Storge)

The Western model of romantic love prioritizes the romantic couple – mother and father (or mom and new romantic boyfriend) over the family unit. Family becomes secondary and subordinate to the romantic couple. This is one of the leading causes for why Western families have collapsed, with romantic love acting as primary agent for disintegration.

Ironically, some conservatives feel they can address the decay by adding a few romantic date nights into the marriage and thereby increase the health of the family. This remedy sounds more like drinking poison to remove the very same poison already causing the sickness.

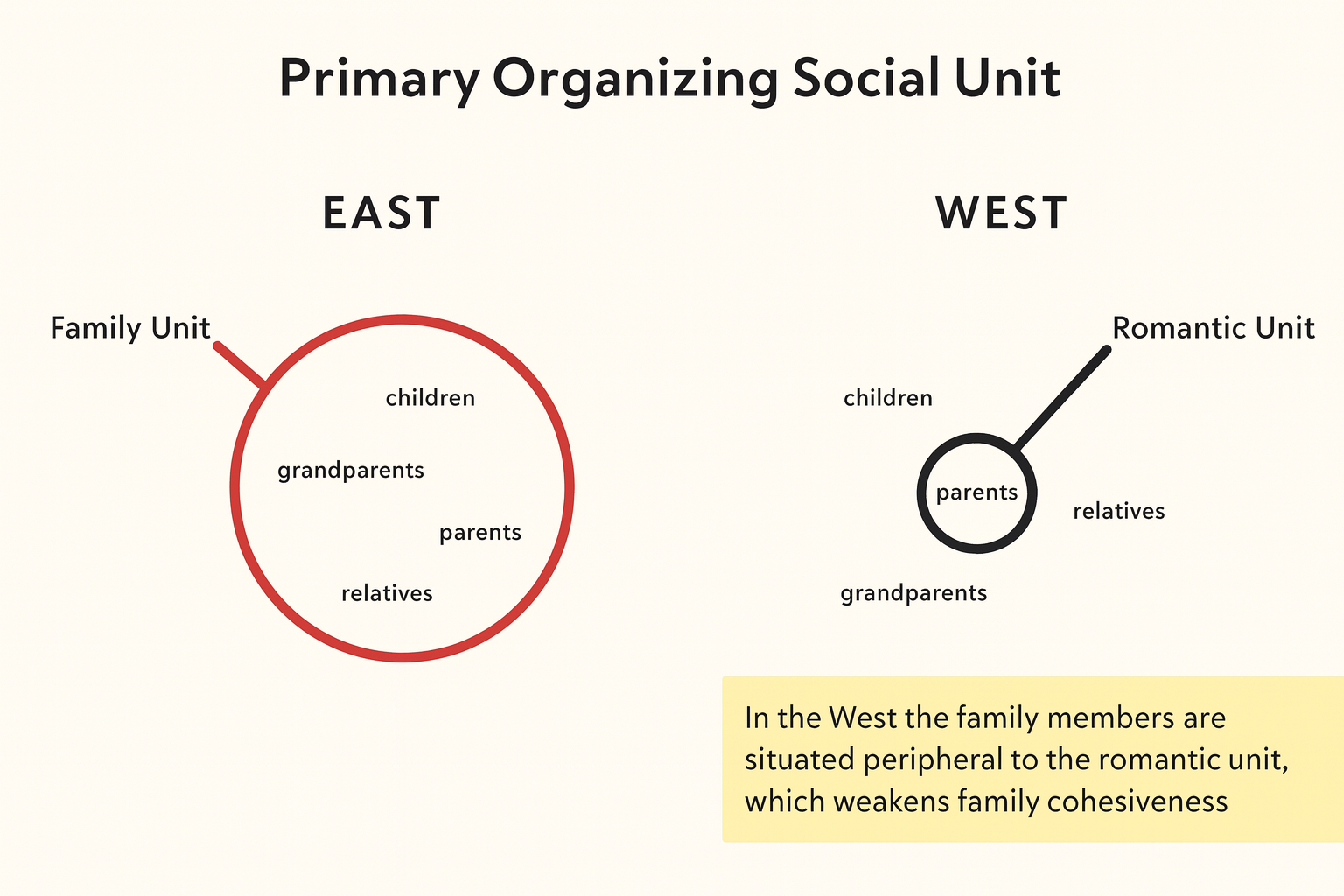

By way of contrast we can see that in traditional cultures the parental couple were subsumed within the family nexus, taking their identity and pride from the family, and serving its needs as their own. Everyone was important: mother, father, children, relatives, and especially grandparents. Today, family is subsumed within the romantic model, if indeed the wider family is considered at all.

This situation was well described by the Twitter/X contributor below who shares his first-hand experience of Chinese and Western cultures:

Another person commented about “the ongoing fallacy of setting up ones familial foundations upon Romantic Love (of the young couple starting a family) versus the classic (now mainly Eastern world view) of having the newly weds become part of the greater familial tapestry, involving extended family.”

The above observations can be summarised by the following graphic contrasting Eastern and Western priorities, which will serve as summary to this article:

Peter Pan Wives Menace To Marriage

Until Peter Pan Syndrome came to be applied exclusively to males, it used to be applied equally to females, as in the article below from the Aberdeen Press and Journal – Friday 04 November 1938. This article describes women who ‘play’ at being helpless in order to garner sympathies and labor from others.

NB. For the sake of accuracy, the female behavior being described here is not strictly that of the Peter Pan archetype (which Jungians refer to as the puer/puella aeternus). The behavior is associated with what the Jungians refer to as the ‘child archetype’ – which is a more helpless presentation than the resourceful youth Peter Pan.

Tolstoy on Romantic Love

Gynocentrism In Marriage Counseling

Christian Churches Conflating Romantic Chivalry with Agape

Many Christian Churches have become temples to romantic love, which began as a worship of women in medieval times by poets and singers who celebrated romantic chivalry, a practice which elevated women to a quasi-divine status. This non-Christian tradition has gained a stranglehold over modern Church culture, to the extent that traditional Christian teachings are becoming obscured in its wake. The following illustrate some of the phenomena that have resulted:

Church and clergy often champion values of romantic love

Which encourages women to conflate Jesus’ love with romantic chivalry

And pressures men to conflate God’s love with romantic chivalry

We are seeing women go on romantic dates with Jesus.

And a growth in the genre of “Christian” romance novels

Also the rise of Christian wives requesting romantic “date nights” from husbands

And finally congregations are singing romantic love songs to God, making evangelical Church worship sound like a Justin Bieber concert encouraging people to “fall in love with, have a love affair with, or become passionate or intimate with Jesus,” while characterizing God as a romantic ravisher of our souls.

Romantic chivalry is a love that’s woman-centered, whereas agape is neighbor centered; Love thy neighbour as thyself. The battle between these two different loves is the crux of a war within the modern Church, because it ultimately confuses and conflates these two contrary motives. To put the problem simply: romantic gynocentrism is not agape.

Does any of this tell us why intelligent men are leaving the Church, and why new men are not coming into it? As always, I invite you be the judge.