Female Aristocracy in English prisons in 1896:

The following is from a Letter To The editor of Reynolds Newspaper in 1896 titled ‘A Privileged And Pampered Sex:

SIR,–A paragraph in your issue of the week before last stated that oakum-picking as a prison task had been abolished for women and the amusement of dressing dolls substituted. This is an interesting illustration of the way we are going at present, and gives cause to some reflection as to the rate at which a sex aristocracy is being established in our midst. While the inhumanity of our English prison system, in so far as it affects men, stands out as a disgrace to the age in the eyes of all Europe, houses of correction for female convicts are being converted into agreeable boudoirs and pleasant lounges. [full newspaper article here]

* * *

Female Aristocracy in American schools in 1900:

In the year 1900 F.E. DeYoe and C. H. Thurber articulated concerns in an article for The School Review which asked, “Where Are the High School Boys?” According to DeYoe and Thurber, a school system that served more girls than boys was a school system headed for disaster. They wrote:

“It is the people’s college, and yet it is obvious that from this people’s college the boys are, for some reason or other, turning away. During most of this century we have been agitating the question of higher education for women. Possibly we have neglected a little to attend to the higher education of boys. Certainly, if we are not to have a comparatively ignorant male proletariat opposed to a female aristocracy, it is time to pause and devise ways and means for getting more of our boys to attend the high school.

We have the anomaly of schools attended chiefly by girls though planned exclusively for boys. A half century ago girls were reluctantly admitted to the high schools and academies as the simplest and most inexpensive way of meeting the cry for justice to women in educational advantages. Now we find the girls apparently driving the boys out of these very schools.”

* * *

Female Aristocracy in American Society in 1909:

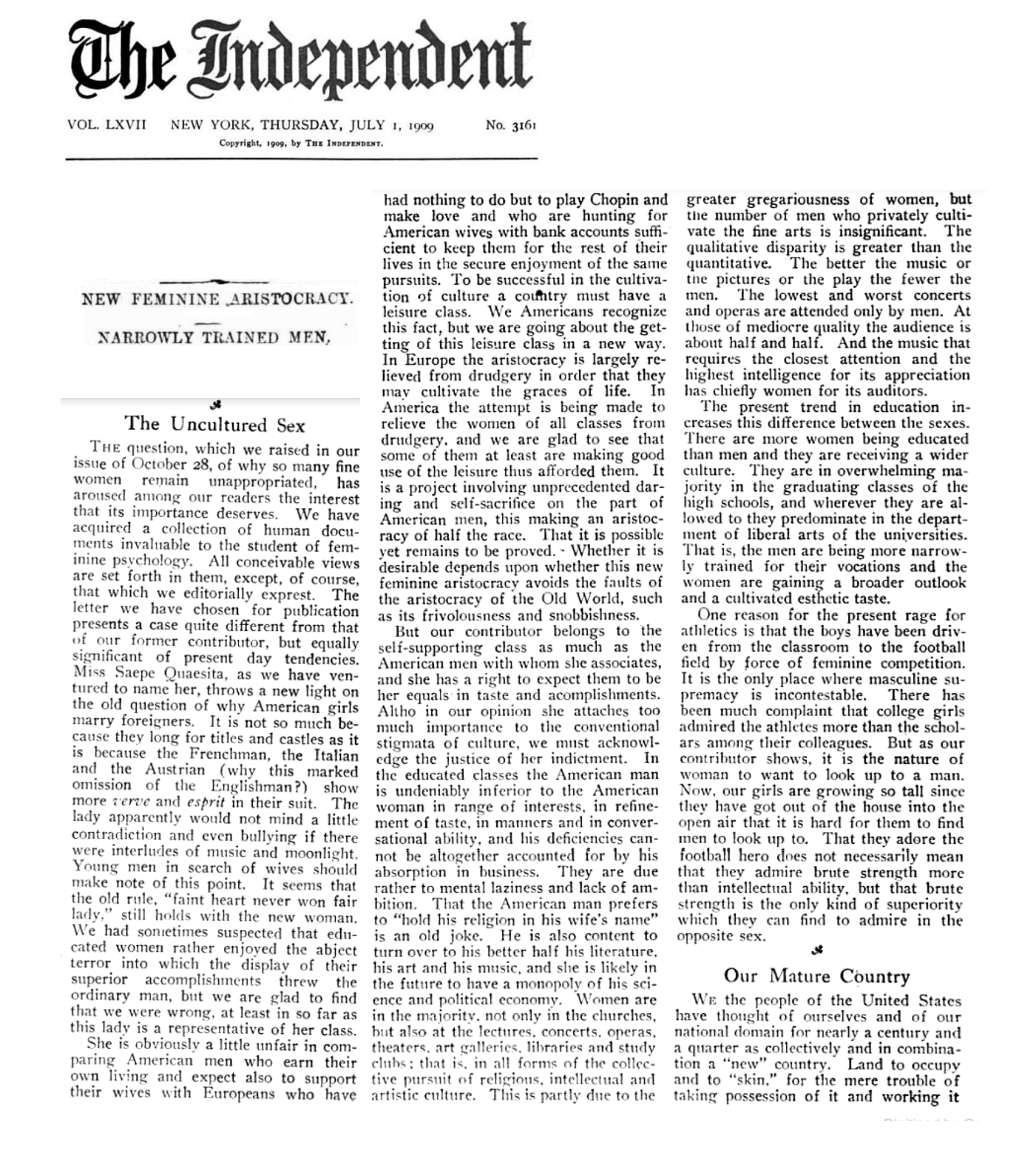

The following is from the The Independent which reported a push to set up a female aristocracy in America. The article was titled The New Aristocracy:

“To be successful in the cultivation of culture a country must have a leisure class,” says the editor. “We Americans recognise this fact, but we are going about the getting of this leisure class in a new way.

“In Europe the aristocracy is largely relieved from drudgery in order that they may cultivate the graces of life. In America the attempt is being made to relieve the women of all classes from drudgery, and we are glad to see that some of them at least are making good use of the leisure thus afforded them. It is a project involving unprecedented daring and self-sacrifice on the part of American men, this making an aristocracy of half the race. That it is possible yet remains to be proved. Whether it is desirable depends upon whether this new feminine aristocracy avoids the faults of the aristocracy of the Old World, such as frivolousness and snobbishness.” [Source: The Independent, Volume 67, 1909]

* * *

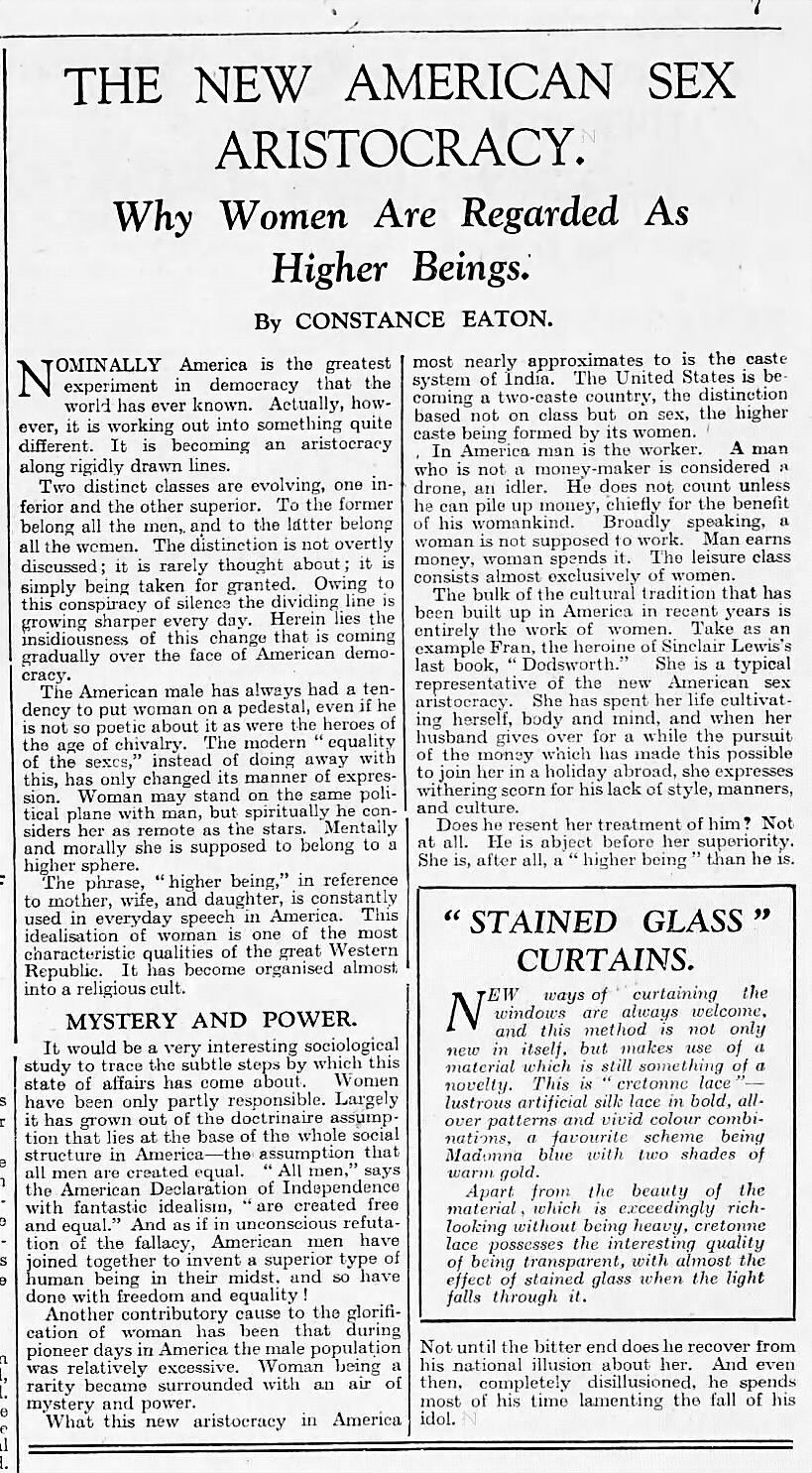

The New American Sex Aristocracy in 1929:

The following was written by Constance Eaton, and published the Daily Telegraph- 16 August 1929.

* * *

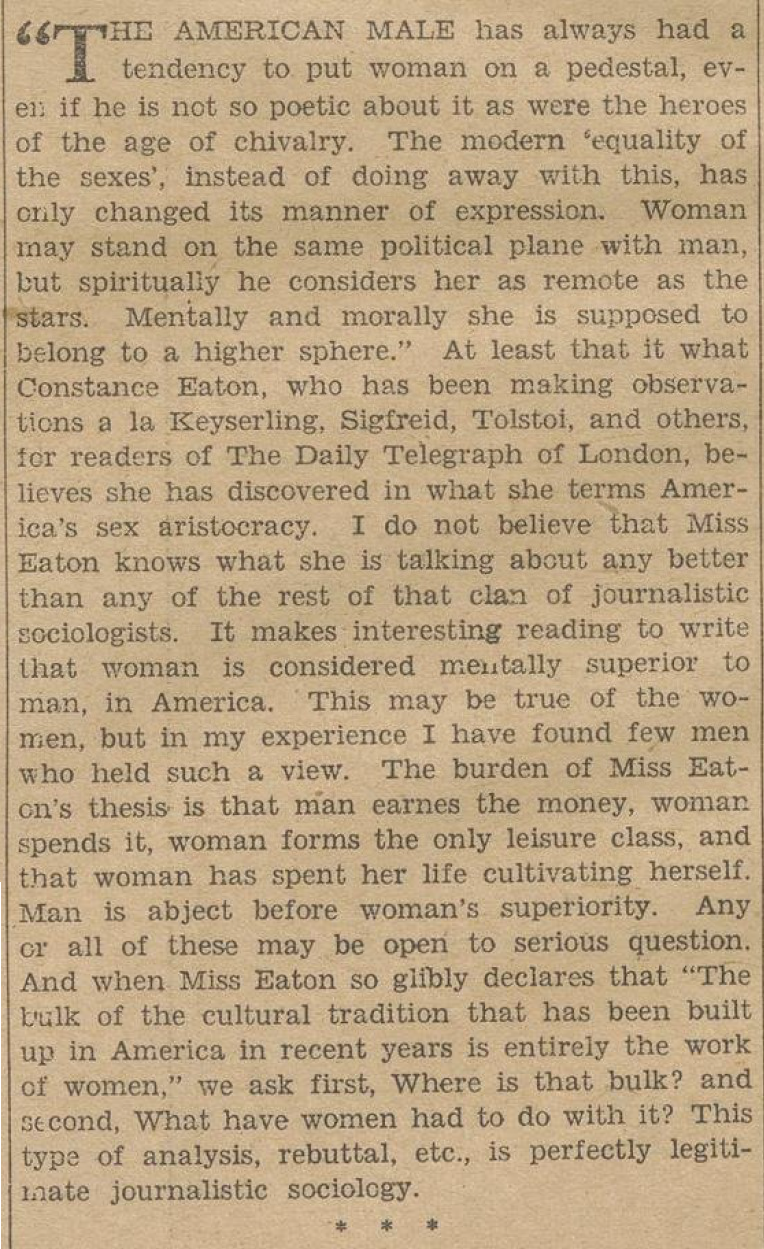

Response to Aristocracy in American Society in 1929:

The following is a journalist’s response to Constance Eaton’s 1929 claim that the sexes have been crafted into social classes – aristocratic women, and their male serfs.

“THE AMERICAN MALE has always had a tendency to put woman on a pedestal, even if he is not so poetic about it as were the heroes of the age of chivalry. The modern ‘equality of the sexes,’ instead of doing away with this, has only changed its manner of expression. Woman may stand on the same political plane with man, but spiritually he considers her as remote as the stars. Mentally and morally she is supposed to belong to a higher sphere.” At least that it what Constance Eaton, who has been making observations a la Keyserling, Sigfreid, Tolstoi, and others, for readers of The Daily Telegraph of London, believes she has discovered in what she terms America’s sex aristocracy. It makes interesting reading to write that woman is considered mentally superior to man, in America. This may be true of the women, but in my experience I have found few men who held such a view. The burden of Miss Eaton’s thesis is that man earns the money, woman spends it, woman forms the only leisure class, and that woman has spent her life cultivating herself. Man is abject before woman’s superiority.

* * *

Another Response to Eaton’s New American Aristocracy

OUR “SEX ARISTOCRACY”

Bertrand Russell arrives with the announcement that our American civilization is the “most feminine since old Egypt,” and Constance Eaton, who has been peering at us curiously for the edification of the readers of the London Daily Telegraph reports that what we really have in America is an aristocracy, not of money, not of blood, nor brains, but of sex. Our men, she finds, place women on a pedestal—on a throne—and they take it seriously and proceed to govern. Man here is the worker. He is the peasant of the field, the brother of the clod, the artisan of the factory, and his mission is to sweat and toil and accumulate spoil to lay at the feet of the lady—the aristocrat who neither toils nor spins. She even does our thinking for us, for Constance Eaton is sure that our culture is wholly of the manufacture of the women. She puts it thus:

“She is a typical representative of the new American sex aristocracy. She has spent her life cultivating herself, body and mind, and when her husband gives over for a while the pursuit of the money which has made this possible to Join her in a holiday abroad, she expresses withering scorn for his lack of style, manners and culture.”

Thus it seems that men in America are in a bad way—pathetic tools of the women—and that our civilization is feminine. At first blush this seems tragic. But, on second thought, does not every one now know that woman is the stronger sex and that her domination makes for strength? These foreign visitors who pounce upon our women and their domination of the men have not found us very romantic or sentimental in International conferences nor on international battlefields. If this is due to our femininity, perhaps we may worry along.

SOURCE: The Evening Sun, dated Wednesday 09 Oct, 1929, Page 4.

* * *

Female Aristocracy in Anglosphere Society – 2011:

By Adam Kostakis:

“It would not be inappropriate to call such a system sexual feudalism, and every time I read a feminist article, this is the impression that I get: that they aim to construct a new aristocracy, comprised only of women, while men stand at the gate, till in the fields, fight in their armies, and grovel at their feet for starvation wages. All feminist innovation and legislation creates new rights for women and new duties for men; thus it tends towards the creation of a male underclass.”

“But what are the women’s rights advocated today? The right to confiscate men’s money, the right to commit parental alienation, the right to commit paternity fraud, the right to equal pay for less work, the right to pay a lower tax rate, the right to mutilate men, the right to confiscate sperm, the right to murder children, the right to not be disagreed with, the right to reproductive choice and the right to make that choice for men as well. In an interesting legal paradox, some have advocated – with success – that women should have the right to not be punished for crimes at all. The eventual outcome of this is a kind of sexual feudalism, where women rule arbitrarily, and men are held in bondage, with fewer rights and far more obligations.”

* * *

See Also: USA, champion of extreme gynocentrism