The following excerpts describing gynocentric-chivalry are taken from Sir Walter Scott’s 1818 essay in the volume Essays on Chivalry, Romance, and the Drama

* * *

The main ingredient in the spirit of Chivalry, second in force only to the religious zeal of its professors, and frequently predominating over it, was a devotion to the female sex, and particularly to her whom each knight selected as the chief object of his affection, of a nature so extravagant and unbounded as to approach to a sort of idolatry. The original source of this sentiment is to be found, like that of Chivalry itself, in the Customs and habits of the northern tribes who possessed, even in their rudest state, so many honourable and manly distinctions, over all the other nations in the same stage of society. The chaste and temperate habits of these youth, and the opinion that it was dishonourable to hold sexual intercourse until the twentieth year was attained, was in the highest degree favourable not only to the morals and health of the ancient Germans, but must have contributed greatly to place their females in that dignified and respectable rank which they held in society.

____________________________

Amid the various duties of knighthood, that of protecting the female sex, respecting their persons, and redressing their wrongs, becoming the champion of their cause, and the chastiser of those by whom they were injured, was represented as one of the principal objects of the institution. Their oath bound the new-made knights to defend the cause of all women without exception ; and the most pressing way of conjuring them to grant a boon was to implore it in the name of God and the ladies. The cause of a distressed lady was, in many instances, preferable to that even of the country to which the knight belonged. Thus, the Captal de Buche, though an English subject, did not hesitate to unite his troops with those of the Comte de Foix, to relieve the ladies in a French town, where they were besieged and threatened with violence by the insurgent peasantry.

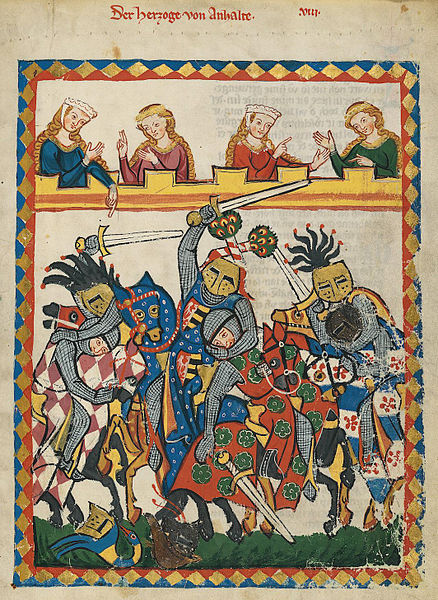

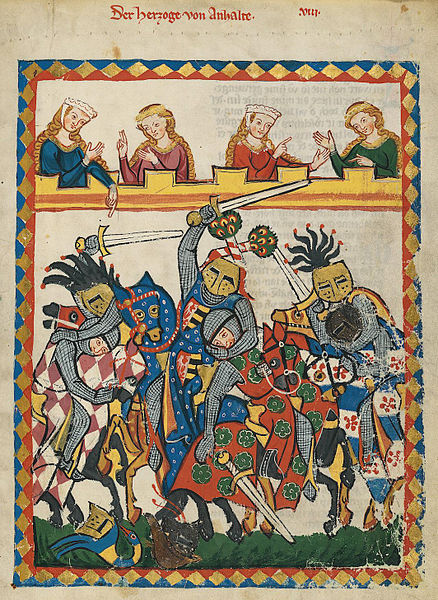

The looks, the words, the sign of a lady, were accounted to- make knights at time of need perform double their usual deeds of strength and valour. At tournaments and in combats, the voices of the ladies were heard like those of the German females in former battles, calling on the knights to remember their fame, and exert themselves to the uttermost. “Think, gentle knights,” was their cry, “upon the wool of your breasts, the nerve of your arms, the love you cherish in your hearts, and do valiantly for ladies behold you.” The corresponding shouts of the combatants were, “Love of ladies! Death of warriors! On, valiant knights, for you fight under fair eyes? Where the honour or love of a lady was at stake, the fairest prize was held out to the victorious knight, and champion from every quarter were sure to hasten to combat in a cause so popular. Chaucer, when he describes the assembly of the knights who came with Arcite and Palemon to fight for the love of the fair Emilie, describes the manners of his age in the following lines;

“For every knight that loved chivalry,

And would his thankes have a passant name,

Hath pray’d that he might ben of that game,

And well was him that thereto chusen was.

For if there fell to-morrow such a case,

Ye knowen well that every lusty knight

That loveth par amour, and hath his might,

Were it in Engellande, or elleswhere,

They wold hir thanked willen to be there.

To fight for a lady! Ah! Benedicite,

It were a lusty sight for to see.”

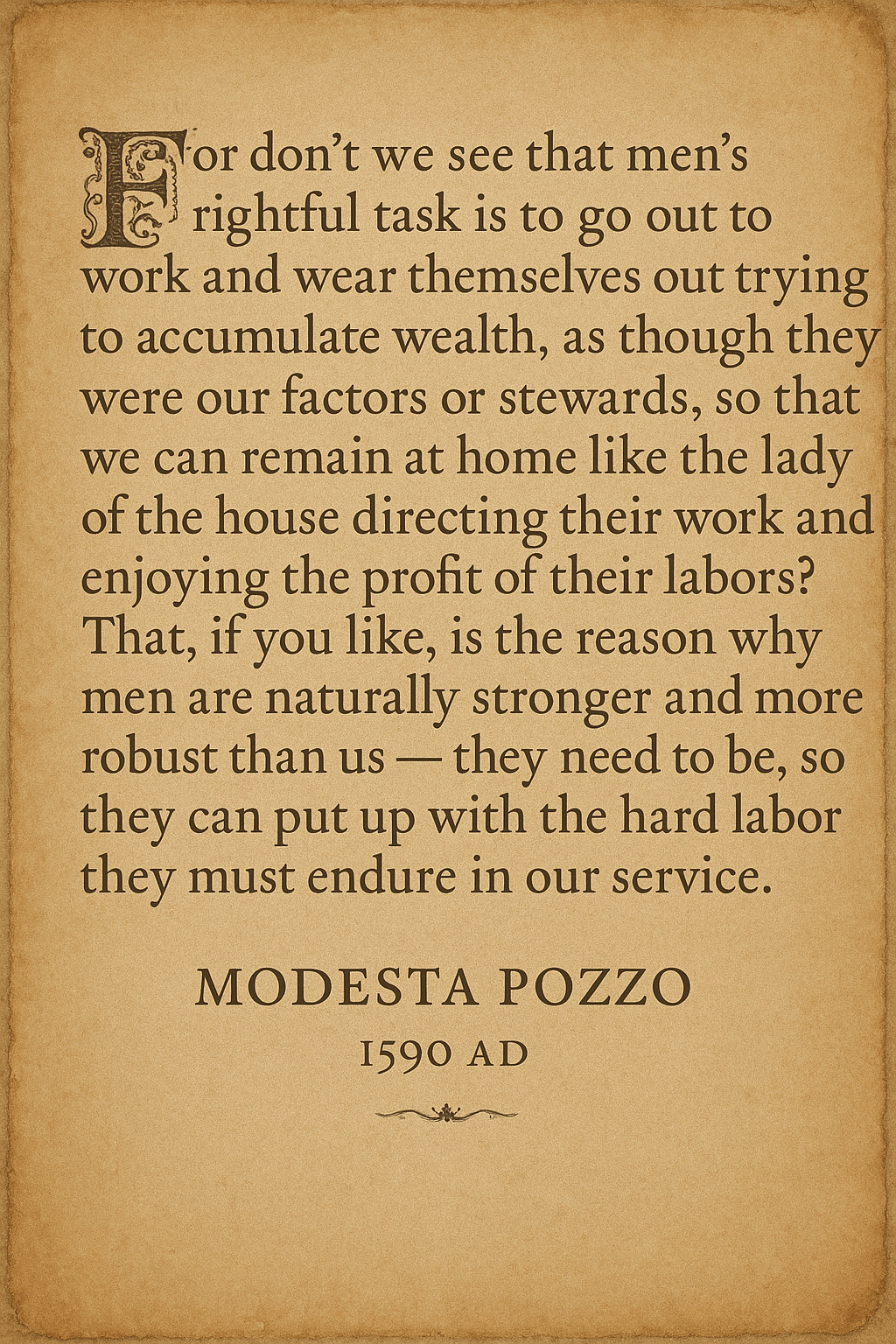

It is needless to multiply quotations on a subject so trite and well known. The defence of the female sex in general, the regard due to their honour, the subservience paid to their commands, the reverent awe and courtesy, which, in their presence, forbear all unseemly words and actions, were so blended with the institution of Chivalry as to form its very essence. But it was not enough that the “very perfect, gentle knight,” should reverence the fair sex in general. It was essential to his character that he should select, as his proper choice, “a lady and a love,” to be the polar star of his thoughts, the mistress of his affections, and the directress of his actions. In her service, he was to observe the duties of loyalty, faith, secrecy, and reverence. Without such an empress of his heart, a knight, in the phrase of the times, was a ship without a rudder, a horse without a bridle, a sword without a hilt ; a being, in short, devoid of that ruling guidance and intelligence, which ought to inspire his bravery, and direct his actions. The least dishonest thought or action was, according to her doctrine, sufficient to forfeit the chivalrous lover the favour of his lady.

It seems, however, that the greater part of her charge concerning incontinence is levelled against such as haunted the receptacles of open vice ; and that she reserved an exception (of which, in the course of the history, she made liberal use) in favour of the intercourse which, in all love, honour, and secrecy, might take place, when the favoured and faithful knight had obtained, by long service, the boon of amorous mercy from the lady whom he loved par amours.In these extracts are painted the actual manners of the age of Chivalry. The necessity of the perfect knight having a mistress, whom he loved par amours, the duty of dedicating his time to obey her commands, however capricious, and his strength to execute extravagant feats of valour, which might redound to her praise, –for all that was done for her sake, and under her auspices, was counted her merit, as the victories of their generals were ascribed to the Roman Emperors— was not a whit less necessary to complete the character of a good knight.

__________________________

On such occasions, the favoured knight, as he wore the colours and badge of the lady of his affections, usually exerted his ingenuity in inventing some device or cognisance which might express their love, either openly, as boasting of it in the eye of the world, or in such mysterious mode of indication as should only be understood by the beloved person if circumstances did not permit an avowal of his passion. The ladies, bound as they were in honour to requite the passion of their knights, were wont, on such occasions, to dignify them by the present of a scarf, ribbon, or glove, which was to be worn in the press of battle and tournament. These marks of favour they displayed on their helmets, and they were accounted the best incentives to deeds of valour. The custom appears to have prevailed in France to a late period, though polluted with the grossness so often mixed with the affected refinement and gallantry of that nation.

Sometimes the ladies, in conferring these tokens of their favour, saddled the knights with the most extravagant and severe conditions. But the lover had his advantage in such cases, that if he ventured to vencounter the hazard imposed, and chanced to survive it, he had, according to the fashion of the age, the right of exacting, from the lady, favours corresponding in importance.

The annals of Chivalry abound with stories of cruel and cold fair ones, who subjected their lovers to extremes of danger, in hopes that they might get rid of their addresses, but were, upon their unexpected success, caught in their own snare, and, as ladies who would not have their name made the theme of reproach by every minstrel, were compelled to recompense the deeds which their champion had achieved in their name.

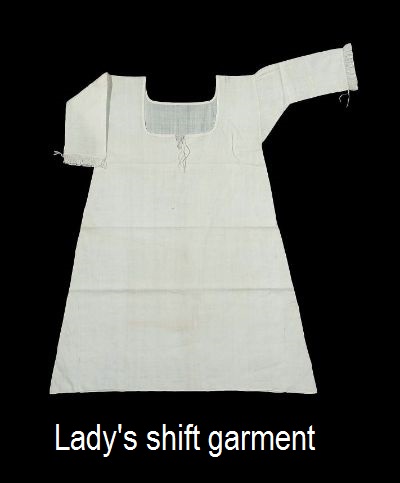

There are instances in which the lover used his right of reprisals with some rigour, as in the well-known fabliau of the three knights and the shift; in which a lady proposes to her three lovers, successively, the task of entering, unarmed, into the mêlée of a tournament, arrayed only in one of her shift. The perilous proposal is declined by two of the knights and accepted by the third, who thrusts himself, in the unprotected state required, into all the hazards of the tournament, sustains many wounds, and carries off the prize of the day.

On the next day the husband of the lady (for she was married) was to give a superb banquet to the knights and nobles who had attended the tourney. The wounded victor sends the shift back to its owner, with his request, that she would wear it over her rich dress on this solemn occasion, soiled and torn as it was, and stained all over with the blood of its late wearer. The lady did not hesitate to comply, declaring, that she regarded this shift, stained with the blood of her “fair friend, as more precious than if it were of the most costly materials.” Jaques de Basin, the minstrel who relates this curious tale, is at a loss to say whether the palm of true love should be given to the knight or to the lady on this remarkable occasion. The husband, he assures us, had the good sense to seem to perceive nothing uncommon in the singular vestment with which his lady was attired, and the rest of the good company highly admired her courageous requital of the knight’s gallantry. It was the especial pride of each distinguished champion, to maintain, against all others, the superior worth, beauty, and accomplishments of his lady; to bear her picture from court to court, and support, with lance and sword, her superiority to all other dames, abroad or at home. To break a spear for the love of their ladies, was a challenge courteously given, and gently accepted, among all true followers of Chivalry, and history and romance are alike filled with the tilts and tournaments which took place upon this argument, which was ever ready and ever acceptable. Indeed, whatever the subject of the tournament had been, the lists were never closed until a solemn course had been made in honour of the ladies.

There were knights yet more adventurous, who sought to distinguish themselves by singular and uncommon feats of arms in honour of their mistresses; and such was usually the cause of the whimsical and extravagant vows of arms which we have subsequently to notice. To combat against extravagant odds, to fight amid the press of armed knights without some essential part of their armour, to do some deed of audacious valour in face of friend and foe, were the services by which the knights strove to recommend themselves, or which their mistresses (very justly so called) imposed on them as proofs of their affection.

Sometimes the patience of the lover was worn out by the cold-hearted vanity which thrust him on such perilous enterprises. At the court of one of the German emperors, while some ladies and gallants of the court were looking into a den where two lions were confined, one of them purposely let her glove fall within the palisade which enclosed the animals, and commanded her lover, as a true knight, to fetch it out to her. He did not hesitate to obey, jumped over the enclosure ; threw his mantle towards the animals as they sprung at him; snatched up the glove, and regained the outside of the palisade. But when in safety, he proclaimed aloud, that what he had achieved was done for the sake of his own reputation, and not for that of a false lady, who could, for her sport and cold-blooded vanity, force a brave man on a duel so desperate. And, with the applause of all that were present, renounced her love for ever. This, however, was an uncommon circumstance. In general, the lady was supposed to have her lover’s character as much at heart as her own, and to mean by pushing him upon enterprises of hazard give him an opportunity of meriting her good graces, which she could not with honour confer upon one undistinguished by deeds of chivalry.

Source:Essays on Chivalry, Romance, and the Drama, by Sir Walter Scott