The sexual relations contract encoded in courtly love fiction was at first celebrated among the upper classes, but made its way by degrees eventually to the middle classes, and finally to the lower classes – or rather it broke class structure altogether in the sense that all Western peoples became inheritors of the customs of romantic love regardless of their social station.

Today the romantic novel is the biggest grossing genre of literature worldwide, with its themes saturating popular culture and its conventions informing politics and legislation globally.

Upper-class beginnings

The three-stage evolution of romantic love saw its first chapter begin in 12th century France. Eleanor of Aquitaine and her daughter Marie De Champagne together elaborated the military notion of chivalry into a notion of servicing ladies, a practice otherwise known as ‘courtly love.’

Courtly love was enacted by minstrels, playrights and troubadours, and especially via hired romance-writers like Chrétien de Troyes who wrote stories to illustrate its principles. Under the continuing guidance of Marie it was elaborated into a code of conduct by Andreas Capellanus in his famous tract titled ‘De amore’ (in English The Art of Courtly Love).

The aristocratic classes who developed this trope did not exist in a vacuum. The courtly themes they enacted would most certainly have captured the imaginations of the lower classes though public displays of pomp and pageantry, troubadours and tournaments, minstrels and playwrights, the telling of romantic stories, and of course the gossip flowing everywhere which would have exerted a powerful effect on the peasant imagination.

We cannot know for certain but it is likely that those of even lower classes adopted some assumptions portrayed in the public displays of courtly love, such as the importance of chivalrous behavior toward women and perhaps a belief in the Lady-like purity and moral superiority of women. Lucrezia Marinella provides just such an example of Venetian society from the year 1600:

It is a marvelous sight in our city to see the wife of a shoemaker or butcher or even a porter all dressed up with gold chains round her neck, with pearls and valuable rings on her fingers, accompanied by a pair of women on either side to assist her and give her a hand, and then, by contrast, to see her husband cutting up meat all soiled with ox’s blood and down at heel, or loaded up like a beast of burden dressed in rough cloth, as porters are.

At first it may seem an astonishing anomaly to see the wife dressed like a lady and the husband so basely that he often appears to be her servant or butler, but if we consider the matter properly, we find it reasonable because it is necessary for a woman, even if she is humble and low, to be ornamented in this way because of her natural dignity and excellence, and for the man to be less so, like a servant or beast born to serve her.

Women have been honored by men with great and eminent titles that are used by them continually, being commonly referred to as donne, for the name donna means lady and mistress. When men refer to women thus, they honor them, though they may not intend to, by calling them ladies, even if they are humble and of a lowly disposition. In truth, to express the nobility of this sex men could not find a more appropriate and fitting name than donna, which immediately shows women’s superiority and precedence over men, because by calling women mistress they show themselves of necessity to be subjects and servants.1

Middle class adaptation

The Victorian era saw the birth of mass novel writing, with much of it written by female authors. Whatever aspirations women had to romantic love in previous centuries, it was now actualized in writings by and about middle-class women, and the themes penned would become ritually enacted, ie. lived, by millions. This development is viewed by some researchers as marking a liberating revolution for middle class women.

Victorian peoples loved the traditional medieval romances of knights and ladies and they hoped to regain some of that noble, courtly behaviour and impress it upon the people both at home and in the wider empire. A new approach however saw it pitched beyond the upper classes to a larger group of people.

In her book Male Masochism, Carol Siegal2 gives an overview of Victorian women’s novels by focusing on the continuation and evolution of the romantic love themes found in medieval romances:

“A great deal of what [Victorian] women’s literary works had to say about gender relations may have been as disquieting as feminist political manifestos, and ironically so, in that the novels seem most anti-male in the very places where they most affirm a traditionally male vision of love. While women’s lyric poetry tended to reverse the conventional gender roles in love by representing the female speaker as the lover instead of the object of love, women’s fiction most frequently reproduced the images, so common in prior texts by men, of the self-abasing male lover and his exacting mistress. For example, in Wuthering Heights, Heathcliff declares himself Cathy’s slave; in Jane Eyre, Rochester’s desire for Jane is first inspired and then intensified by his physically dependent position; in Middlemarch, Will Ladislaw silently vows that Dorothea will always have him as her slave, his only claim to her love lies in how much he has suffered for her. In several Victorian novels by women, men must undergo quasi-ritualized humiliation or punishment before being judged deserving of their lady’s attention. For instance, in Olive Schreiner’s Story of an African Farm, the fair Lyndall condescends to treat her admirers tenderly after one has been horsewhipped and the other has dressed himself in women’s clothes to wait on her. Although Victorian women’s novels do explore the emotional insecurities of the heroines, their apparent self-possession is also stressed, in marked contrast to their lovers’ displays of agony, desperation, and wounds.”

“A great deal of what [Victorian] women’s literary works had to say about gender relations may have been as disquieting as feminist political manifestos, and ironically so, in that the novels seem most anti-male in the very places where they most affirm a traditionally male vision of love. While women’s lyric poetry tended to reverse the conventional gender roles in love by representing the female speaker as the lover instead of the object of love, women’s fiction most frequently reproduced the images, so common in prior texts by men, of the self-abasing male lover and his exacting mistress. For example, in Wuthering Heights, Heathcliff declares himself Cathy’s slave; in Jane Eyre, Rochester’s desire for Jane is first inspired and then intensified by his physically dependent position; in Middlemarch, Will Ladislaw silently vows that Dorothea will always have him as her slave, his only claim to her love lies in how much he has suffered for her. In several Victorian novels by women, men must undergo quasi-ritualized humiliation or punishment before being judged deserving of their lady’s attention. For instance, in Olive Schreiner’s Story of an African Farm, the fair Lyndall condescends to treat her admirers tenderly after one has been horsewhipped and the other has dressed himself in women’s clothes to wait on her. Although Victorian women’s novels do explore the emotional insecurities of the heroines, their apparent self-possession is also stressed, in marked contrast to their lovers’ displays of agony, desperation, and wounds.”

Siegal suggests that male masochism and the dominatrix-like behavior of women in these writings is continuous with courtly love literature from the Middle Ages. And whilst some libertines self-consciously chose their lowly position in relation to women, the men described in Victorian women’s novels lacked such volition:

“These texts also insist that the true measure of male love is lack of volition. While the heroines make choices that define them morally, the heroes are helplessly compelled by love, and not judged to love unless they are helpless. In this respect Victorian women’s fiction recovers the ethos so often expressed in medieval courtly romance that love must be “suffered as a destiny to be submitted to and not denied.” It also departs from the conventions of medieval romance in describing the helpless submission to love as an attribute of true manliness, and thus Victorian women’s fiction directly attacks the degeneration of chivalry into the self-conscious and controlled “gallantry” of eighteenth century libertines.”

“These texts also insist that the true measure of male love is lack of volition. While the heroines make choices that define them morally, the heroes are helplessly compelled by love, and not judged to love unless they are helpless. In this respect Victorian women’s fiction recovers the ethos so often expressed in medieval courtly romance that love must be “suffered as a destiny to be submitted to and not denied.” It also departs from the conventions of medieval romance in describing the helpless submission to love as an attribute of true manliness, and thus Victorian women’s fiction directly attacks the degeneration of chivalry into the self-conscious and controlled “gallantry” of eighteenth century libertines.”

Those who have read medieval romance literature will agree with Siegal that the sexual relations contract embedded in Victorian Romance novels provides the continuation of a medieval trope, and not a fresh vision generally speaking. It is an example of pastiche.

To be sure there are new elements in the Victorian novel, such as the stronger emphasis on emotion and the relaxing of class distinctions, but we are not dealing with a new animal in terms of larger trope structure, i.e. it is more like a new costume for an old play.

Said another way, the essence of the feudal relationship was extracted from the medieval class system in which it was born, and applied by authors of the Victorian era to people of the middle classes. With a passage of time and a further dissolving of class distinctions to which this trope might apply, it would be eventually applied to all people – class codes be damned.

The medieval structure in question is one we might call sexual feudalism. It is symbolized, for example, in the marriage proposal which sees men of any class go down on one knee – a ceremony originally intended for a feudal relationship contract in medieval times.

C.S. Lewis referred to the transfer of the feudal contract into intimate relations as “the feudalisation of love,” making the observation that it has left no corner of our ethics, our imagination, or our daily life untouched. And perhaps more importantly this sexual feudalism – or romantic love as it is popularly called – no longer relies on a feudal society or class structures for its existence.

Taking an earnest look at the power wielded by protagonists in the Victorian woman’s novel, and of the novel’s real-world consequences for women, Nancy Armstrong3 observes that the sexual contract can overrule the social contract, and that love can be the most powerful regulating law between two parties – a possibility that appears little considered by feminist writers.

Adaption by all levels of society

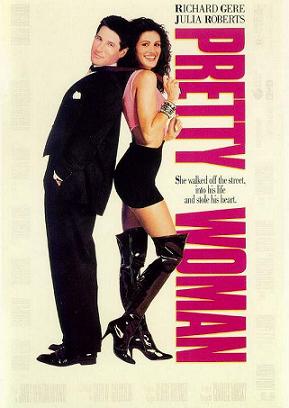

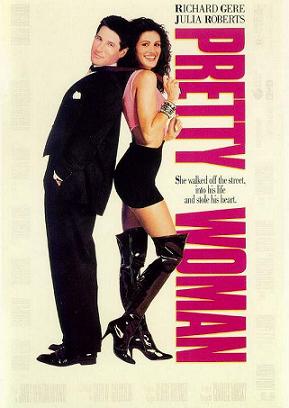

Romantic love today is the great leveler, smashing all class distinctions in its path. Women of low means can marry men of high station (and visa versa) because the love contract is capable of overruling the social contract. While there are literally millions of novels and movies that display feudalistic love overriding the social contract, the movie Pretty Woman, featuring Richard Gere and Julia Roberts, will suffice as a modern example:

Edward Lewis, a successful corporate raider in Los Angeles on business, accidentally ends up on Hollywood Boulevard in the city’s red-light district, after breaking up with his girlfriend during an unpleasant phone call. Leaving a party, he takes his lawyer’s Lotus Esprit luxury car, and encounters a prostitute, Vivian Ward. He stops for her, having difficulties driving the car, and asks for directions to Beverly Hills. He asks her to get in and guide him to the Beverly Hills Regent Hotel, where he is staying. It becomes clear that Vivian knows more about the Lotus than he does, and he lets her drive. Vivian charges Lewis $20 for the ride, and they separate. She goes to a bus stop, where he finds her and offers to hire her for the night; later, he asks Vivian to play the role his girlfriend has refused, offering her $3000 to stay with him for the next six days as well as paying for a new, more acceptable wardrobe for her. That evening, visibly moved by her transformation, Edward begins seeing Vivian in a different light. He begins to open up to her, revealing his personal and business lives.

Edward takes Vivian to a polo match in hopes of networking for his business deal. His attorney, Phillip, suspects Vivian is a corporate spy, and Edward tells him how they truly met. Phillip later approaches Vivian, suggesting they do business once her work with Edward is finished. Insulted, and furious that Edward has revealed their secret, Vivian wants to end the arrangement. Edward apologizes, and admits to feeling jealous of a business associate to whom Vivian paid attention at the match. Vivian’s straightforward personality is rubbing off on Edward, and he finds himself acting in unaccustomed ways.

Clearly growing involved, Edward takes Vivian in his private jet to see La Traviata in San Francisco. Vivian is moved to tears by the story of the prostitute who falls in love with a rich man; after the opera, they appear to have fallen in love. Vivian breaks her “no kissing on the mouth” rule (which her friend Kit taught her), and he offers to put her up in an apartment so she can be off the streets. Hurt, she refuses, says this is not the “fairy tale” she dreamed of as a child, in which a knight on a white horse rescues her.

Meeting with the tycoon whose shipbuilding company he is in the process of “raiding,” Edward changes his mind. His time with Vivian has shown him a different way of looking at life, and he suggests working together to save the company rather than tearing it apart and selling off the pieces. Phillip, furious at losing so much money, goes to the hotel to confront Edward, but finds only Vivian. Blaming her for the change in Edward, he attempts to rape her. Edward arrives, punches him in the face, and throws him out.

With his business in L.A. complete, Edward asks Vivian to stay one more night with him — because she wants to, not because he’s paying her. She refuses. On his way to the airport, Edward re-thinks his life and has the hotel chauffeur detour to Vivian’s apartment building, where he leaps from out the white limo’s sun roof and “rescues her,” an urban visual metaphor for the knight on a white horse of her dreams.4

The trope of romantic love is ubiquitous and pervasive through all levels of Westernized culture, and is rapidly infusing into remaining pockets of Asia that had been historically secluded from its influence. Romantic love is the number one selling genre in literature, movies and music globally – a testament to its all encompassing power.

The fact that women have been front-and-center in crafting and promoting this medieval “love” contract flies in the face of women’s presumed powerless in the world. The two-spheres approach underlining powers unique to males and females is at play, and while only 1% of males traditionally controlled the political sphere, 100% of women possess the leverage of romantic love in the relational sphere. Further, I would go so far as to claim the political sphere governed by that 1% of men is now so captivated by the dictates of romantic love that its mission has become synonymous with the enactment of chivalry, both in social project spending, and in law.

The old saying is “Love conquers all.” However the author of that phrase had in mind a very different kind of love from the all-conquering power we today refer to as romantic love, and women have played a pivotal role in bringing the later to bear.

Sources:

[1] Lucrezia Marinella, The Nobility and Excellence of Women and the Defects and Vices of Men (1600) Translated by Anne Dunhill, Published by University of Chicago Press

[2] Carol Siegal, Male Masochism, Indiana University Press, 1995 (pp. 12-13)

[3] Nancy Armstrong, Desire and Domestic Fiction: A Political History of the Novel, Oxford University Press, 1990

[4] Pretty Woman plot, from Wikipedia

_____________________________

Addendum:

I’m suspicious of scholarly works which “find” romantic love all over the world and in all periods. After reading many such essays I’ve come to the conclusion they confine themselves to biological universals such as the desire for sex, the need for attachment, limerence, social interaction and so on and so forth — all of which falls short of the complex European-derived phenomenon known as courtly & romantic love.

Those academic descriptions omit the idiosyncratic elements that might cast doubt on their universality thesis – details like male masochism, uniquely stylized feudal relationships from France or Germany, the conceptualization of the Virgin Mary and her purity and how that plays into conceptions of gender and love, along with other complex behaviors and influences which make up the courtly love complex arising in medieval Europe.

When Gaston Paris first coined the phrase ‘Courtly Love’ (1883) he was referring precisely to those idiosyncratic elements that render the phenomenon distinct from the universals many scholars reduce it to.

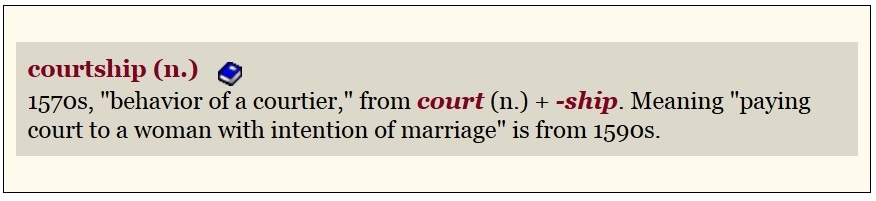

Gaston Paris’ description of courtly love can be summarized as follows:

“It is illicit, furtive and extra-conjugal; the lover continually fears lest he should, by some misfortune, displease his mistress or cease to be worthy of her; the male lover’s position is one of inferiority; even the hardened warrior trembles in his lady’s presence; she, on her part, makes her suitor acutely aware of his insecurity by deliberately acting in a capricious and haughty manner; love is a source of courage and refinement; the lady’s apparent cruelty serves to test her lover’s valor; finally, love, like chivalry and courtoisie, is an art with its own set of rules.” 1

Thus courtly love as defined by Paris has four distinctive traits;

1. It is illegitimate and furtive

2. The male lover is inferior and insecure; the beloved is elevated; haughty; even disdainful.

3. The lover must earn the lady’s affection by undergoing tests of prowess, valor and devotion.

4. The love is an art and a science, subject to many rules and regulations — like courtesy in general.

It’s clear that what we call romantic love today continues each of these conventions with the sole exception of illegitimacy and furtiveness. With this one exception romantic love can be regarded as coextensive with the courtly love described by Paris.

Many scholars researching this area conveniently overlook (or refuse to mention) the sexual feudalism inherent to the European-descended model of romantic love. Attempts to homogenise and cast romantic love as a global universal, while avoiding all mention of the unsavory sexual feudalism that might render it more problematic and complex, is unhelpful to say the least, and misleading at worst. European-descended romantic love, now the dominant version globally, deserves to be considered separately and need not be confused with more simple theoretical constructs on offer.

Note: [1] Roger Boase, The Origin and Meaning of Courtly Love: A Critical Study of European Scholarship, p.24, Manchester University Press, 1977

In a recent interview Jordan Peterson took the opportunity to clarify his position on the vexed question ‘are the sexes different or the same,’ which he definitively answers in favour of males and females being more alike than they are different. – PW

In a recent interview Jordan Peterson took the opportunity to clarify his position on the vexed question ‘are the sexes different or the same,’ which he definitively answers in favour of males and females being more alike than they are different. – PW