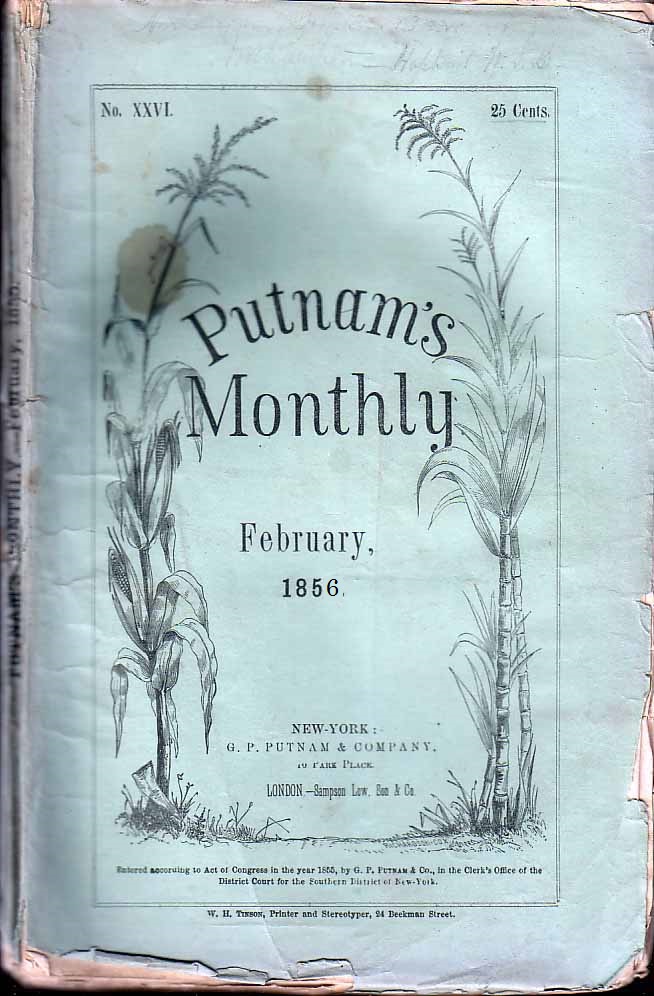

The following long article from 1856 discusses the sexist laws that oppressed men and benefited women, including the practice of frivolous, unjustified lawsuits for supposed breach of marriage promise (or implied promise, or imagined promise). Such suits came, by the late part of the nineteenth century to be a standard operating procedure for women who either felt genuinely spurned or, just as frequently, women who saw an opportunity to misuse laws to control men. By the late 1920s, the practice had become a widespread criminal enterprise, highly profitable for both weeping bogus sweetheart and racketeering lawyer that it gained the appellation, “The Heart Balm Racket.”

***

— A Word for Men’s Rights —

FULL TEXT: The notions which rule inside of men’s heads, and the phrases in vogue to represent them are hardly less liable to fluctuation than is the fashion of the outward adornment, whether by hats, caps, bonnets, periwigs, or powder. Sixty or seventy years ago, scarcely anything was so much talked of as the rights of man. Where this phrase came from, we cannot tell. It is not to be met with in any writer of prior date to the middle of the last century. James Otis used it in his famous tract on the Rights of the American Colonies, nor are we aware of any earlier appearance of it in print. Sudden, however, and obscure as its first appearance was, it took, and soon became one of the most fashionable of phrases. It played a great part in the American Revolution. It found its way into our Declaration of Independence, and into the fundamental laws of most of our states. It played a still greater part in the French revolution. Ten or a dozen French constitutions, more or less, were founded upon it. Thomas Paine wrote a famous book, with this title. For a while, nothing was so much talked of as the rights of man—talked of, we say—for, as happened in the case of the thirsty Indian, so with respect to these rights, it was pretty much all talk, with very little cider.

In sixty years, however, fashions have changed. The rights of man —once in everybody’s mouth—are seldom heard of now-a-days—unless it be in an abolition convention—or, if mentioned at all, in Congress and other respectable places, these rights, once the hope of humanity, are referred to, only to be sneered at, as a flourish of rhetoric—a chimera of the imagination.

Still, we are not left speechless nor hopeless. Hope still remains at the bottom of the box, with a fine sounding phrase to back it. Let the men go to the deuce. What of that? Does not lovely woman still remain to us? Today, the fashionable phrase is—woman’s rights. The women have discovered, or think they have, that they are, and long have been tyrannized over, in the most brutal manner, by society, the laws, and their husbands. Woman’s rights is now the watch-word of a new movement for social reform, and even for political revolution—the women, among other things, claiming to vote.

It must be confessed that such general outcries are not commonly raised, without some reason. They are the natural expressions of pain and unsatisfied desire. It was not without reason that America and Europe, towards the close of the last century, raised the cry of the rights of man; and so, we dare say, it is not without reason that the rights of woman are now dinged into our ears. Nor is this cry without a marked effect, not merely upon manners and society, but also upon laws. Almost all our state legislatures are at work, with more or less diligence and enthusiasm, modifying their statute books, under the influence of this new zeal. To that we do not object. Putnam is for reform. Putnam is for progress. Putnam is for woman’s rights; but also for man’s rights—for everybody’s rights; and, in that spirit, we are going to offer a few hints to our legislators, whose vaulting zeal, on behalf of the ladies, seems a little in danger of overleaping itself, and jolting on t’other side. It is well to stand straight, but not well to tumble over backward, in attempting to do so.

Those who go about to modify our existing laws, as to the relation of husband and wife, will do well to reflect that the old English common law on this subject, if it be a rude and barbarous system, little suited to our advanced and refined state of society—which we do not deny—is also a consistent and logical system, of which the different parts mutually rest upon and sustain each other. In the repair, or modification of such a system, it is material that every part of it should be taken into account. Changes in one part will involve and require changes in other parts; otherwise, alterations, made with a view only to relieve the wife from tyranny and oppression, may work a corresponding injustice to the husband. Nor are the changes already made in our laws, partly by legislation and partly by usage, free from glaring instances of this sort.

The English common law makes the husband the guardian and master of the wife, who stands to him in the relation of a child and a servant. In virtue of this relation, the husband is legally responsible for the acts of the wife. If she slanders or assaults her neighbors, he is joined with the wife in the action to recover damages, and he alone is legally responsible for the amount of damages recovered, even to the extent of being sent to jail in default of payment. He is likewise responsible for debts contracted by the wife to the same extent that a father is responsible for the debts of his minor children. Even in criminal proceedings, it is he who must pay, or go to jail for not paying the fines imposed on his wife; and there are many cases, even cases of felony, in which the wife, acting in concert with her husband, is excused from all punishment, on the presumption that she acts by his compulsion, though in fact she may, as in the noted case of Macbeth’s wife, have been the instigator. Public opinion goes even further than the law, and holds the husband accountable, to a certain extent, for all misbehaviors and indiscretions on the part of his wife. Not only is he to watch that she does not steal, he is to watch that she does not flirt, and every species of infidelity, or even of levity on her part, inflicts no less disgrace upon him than upon her—disgrace which the received code of honor requires him to revenge upon the male delinquent not only in defiance of the law which forbids all breaches of the peace, but even at the risk of his own life.

The law and public opinion having anciently imposed all these heavy obligations on the husband, very logically and reasonably proceeded to invest him with corresponding powers and authority. Standing to the wife, as he was made to stand, in the relation of father and master, the law very reasonably invested him with all the rights and authority of a father and a master. How, indeed, was he to exercise the authority and to fulfill the obligations which the law and public opinion imposed upon him, of regulating the conduct of his wife, unless invested at the same time with means both of awe and coercion? Accordingly, the law and usage of England authorized the husband to chastise his wife—in a moderate manner—employing for that purpose a rod not thicker than his finger. The husband was also entitled to the personal custody of his wife, and was authorized in proper cases—if, for instance, she seemed disposed to run off with another man—to lock her up, and, if need were, to keep her on bread and water.

Now these, it must be confessed, were extensive powers—harsh and barbarous powers, if you please—though the law always contemplated that, in his exercise of them, the husband would .be checked by the same tenderness towards the wife of his bosom which tempers the exercise by the father of a similar authority over his children. But however extensive, however harsh or barbarous the powers of the husband may be, we appeal even to our female readers — if, indeed, a single female has had patience and temper to follow us thus far—we appeal even to that single female (or married one, as the case may be), to say how, in the name of common sense, is the husband to keep the wife in order, to the extent which the law and public opinion demands of him, except by the exercise of these powers, or at least by the awe which the known possession and possible exercise of them is fitted to inspire? If the fractious child is neither to be spanked nor shut up in the closet, how is domestic discipline to be preserved? What more effectual sedative to an excited and ungovernable temper, which might provoke both suits for assault and actions for slander, than retirement in one’s closet with the door locked and a glass of cold water to cool one’s burning tongue?

And so of another great topic of complaint on the part of the advocates of woman’s rights—the power which the husband has by the common law over the wife’s property. He being responsible for her debts and her acts, and being bound to provide for the support of the children, has, as a corollary thereto, the custody and disposition of the wife’s property, if she chances to inherit or to acquire any—which, unfortunately, in the middle ranks of life, where these notions of woman’s rights most extensively prevail, is, we are sorry to say, but too seldom the case.

Such are the relative rights and duties of the husband under the old English common law. Under this law a husband is not a mere chimera, a surd and impossible quantity. There is a logical consistency about him. He is, as Horace says of the stoic philosopher, terei ef rotundus, round and whole, armed at all points, provided with powers adequate to the duties expected of him.

In America we have no such husbands. Long before the cry of woman’s rights was openly raised, the powers and prerogatives of the American husband had been gradually undermined. Usage superseded law, and trampled it under foot. Sentiment put logical consistency at defiance, and the American husband has thus become a legal monster, a logical impossibility, required to fly without wings, and to run without feet.

Women care nothing for logic, but they have a sense of justice and tender hearts, and to their sense of justice we confidently appeal. Who can wonder that the men are so shy in taking upon them the responsibilities of the married state? Those responsibilities all remain exactly as in old times, while the means of adequately meeting them are either entirely taken away, or are in a fair way to be so. By the law as it now is, we believe in every state of the Union, the husband cannot lay his finger on his wife in the way of chastisement except at the risk of being complained of for assault and battery, and, perhaps, sued for a divorce, and (which is worse than either) of being pronounced by his neighbors a brutal fellow. The nominal custody of the person of the wife, which the law still, in some of the states, affects to bestow upon the husband, is a mere illusion. If he attempts to lock her up, she can sue out her habeas corpus, and oblige him to pay the expenses of it; and if she wishes to quit her husband’s house, and go elsewhere, he has no means of compelling her return. He may sue those with whom , takes refuge, for harboring her, but if he obtain damages at all, they will be only nominal. In many of the states, laws have been enacted and soon will be in all of them, giving the wife the exclusive control of her own property, acquired before or after marriage, by gift, inheritance, or her own industry.

While the wife is thus rendered to a great extent independent of her husband, he, by a strange inconsistency, is still held, both by law and public opinion, just as responsible for her as before. The old and reasonable maxim, that he who dances must pay the piper, not apply to wives—they dance, and the husband pays. To such an extent is this carried, that if the wife beats her husband, and he, having no authority to punish her in kind, applies to the criminal courts for redress, she will be fined for assault and battery, which fine he must pay, even thought she has plenty of money of her own. or, in default of paying, go to jail! Such cases are by no means of unprecedented occurrence in our criminal courts.

Now, what sense or reason is there in making the husband responsible for the licenses of the wife’s tongue, after he has lost all power to control it? If the wife is to hold her property separately, ought she not to be sued separately, both for debts and damages? If her property ought not to go to pay the husband’s debts, why ought his to go to pay hers? If the husband has lost the power to control tile goings in and runnings out of the wife, why ought public opinion to hold him any longer responsible therefor?

We have no objection to an amendment of the law in relation to husband and wife. Public opinion demands it. The progress of society requires it. But the new wine ought not to be put into old bottles, nor the old garments to be patched with new pieces, lest, as the proverb says, the rent be made worse than before.

But there is yet another recent innovation in the law, liable to still more serious objections. Not content with placing the unfortunate husband in an absurd and anomalous condition, not content with still demanding of him certain duties and obligations, at the same time that he is deprived of the powers and the rights essential to their fulfillment, reducing him in fact to a position hardly less ridiculous, and not at all less embarrassing, than that of a short-tail bull in fly-time—the law (as if conscious that, before entering into such an unequal alliance, the men would grow pretty critical as to the personal qualities of the women in whose power they were about so completely to place themselves) seeks to entrap us into matrimony against our inclinations, by holding, as it does, that any man who shows signs of having been impressed by a woman, becomes, if she is single, her lawful prize, and is bound to marry her if she insists upon it, or eke—stand a suit for breach of promise.

Though suits for breach of promise of marriage are comparatively a recent thing, in order fully to understand their nature it is necessary to go back to the dark ages. We pretend to be protestants; we rail against the popish church; yet in how many important matters are we still the mere slaves and tools of that church! The canon law was one of the most crafty devices of the middle age theocracy, and is a standing topic of reproach against Catholicism ; and yet in the most delicate of all our relations, that of marriage and divorce, we protestants are to this day substantially governed by the canon law! The canon law was made by monks, men forbidden to marry themselves, and therefore destitute of any personal experience by which to shape their legislation on this subject. They had, indeed, the Roman law as their guide, but this they departed from in the most essential particulars, as being altogether too reasonable to suit their ascetic theories or serve their purpose. The monks who made the canon law looked upon marriage as a sensual and unholy state, only to be tolerated in the gross laity, to prevent something worse; and they seem to have exerted their whole ingenuity to render this sinful condition as uncomfortable as possible. Hence the excessive hostility of the canon law to divorce, it being held a just punishment of the immorality of marrying at all, that persons Unsuitably or unhappily married should be kept during their natural lives tied together neck and heels, Bo that their torments in this world might give them, as it were, a relishing foretaste of what married sinners had to expect in the next. But while unhappy marriages were thus cursed with a perpetuity beyond the reach of the parties or the law, the ingenious canonists at the same time suspended over the heads of every happy couple the terror of an involuntary and forced separation, which should unmarry them and bastardize their children. One of the means employed for this devilish purpose was the doctrine of pre-contracts. A promise to marry was, according to the canon law, equivalent to a marriage, and every subsequent marriage to another party, pending the life of the party to whom the promise had been made, was vitiated by it. The canonists even went so far as to allow suits for the specific performance of these marriage contracts—the officers of their courts, on the suit of some disappointed virgin, entering the household of love, breaking up the family, stigmatizing the woman as a concubine and her children as illegitimate, and compelling the man to take his legal wife—as by virtue of some pretended pre-contract she was held to be—into his house and his bed. It is from this canonist doctrine of precontracts that our suits for breach of promise are derived. The common law, indeed, being the work of ruder hands, is ignorant of that beneficial process of the Roman law—the suit for specific performance. In the case of the nonperformance of a contract, the common law contents itself with attempting to set matters right, by awarding damages for the non-performance. In this particular case, even this defect in the common law was a very fortunate thing, as otherwise, instead of merely having damages to pay for refusing to marry against our inclination, we might have been brought up to the ring-bolt of specific performance, and forced into the yoke any how.

It is often said that no woman of any delicacy or self-respect ever would or ever does bring a suit for breach of promise of marriage. That may be so; still nothing prevents a great many women, who would be entirely unwilling to confess to any deficiency of delicacy or self-respect, from taking advantage of the law, or more properly speaking, of the public sentiment out of which the law grows and which sustains it, to force their once lovers, but lovers no longer, into a reluctant and repugnant marriage ceremony. Whose private experience does not enable him to recount instances, in which men, sensibility and honor have suffered themselves to be thus forced into unsuitable matches, of which the unfortunate result has corresponded with the inauspicious beginning? Contrary to every principle of common sense, as well as to every instinct of sentiment, as are suits for breach of promise of marriage, yet undoubtedly they are fully sustained by the prevailing public sentiment. Otherwise it would be impossible to explain the extravagant lengths to which courts have gone in inferring a promise of marriage from the most trivial circumstances—waiting on a lady home from church; going to see her of a Saturday night; asking her twice of a winter to a ball; corresponding with her, though nothing is said in the letters about love or marriage; allowing her to darn your stockings. There is, indeed, no circumstance, however light or trivial, upon which the busy tongues of a country parish get up a rumor of an engagement, which is not held amply sufficient by our courts of law to establish the fact of a promise of marriage, and to lay the foundation of a suit for damages.

It is not, however, upon these extreme cases that we rest our opposition. We object to the proceeding in any case, no matter how solemn and formal the promise, nor how often renewed. We object to the whole idea of obligation in such a case, and, of course, to the enforcement of such supposed obligation by law. The whole thing is a gross abuse—to speak the truth—a scandalous abomination. The very idea of marriage, according to any but the grossest and lowest conception of it, implies the free and full consent of both the parties to it. On the part of the man, if not of the woman, it implies something more, not a mere tacit consent, but a forward, active, joyous consent. A great deal of sympathy has been expended over women forced by tyrannical fathers to give their hands without their hearts. A miserable case, truly, but altogether less miserable than that of a man, drawn, by a false sense of honor and a ridiculous public opinion, to speak a public lie, and, in the face of God and man, to pledge himself as a husband, when he knows he cannot be one. All promises are made with this implied reservation—that he who promises shall have it in his power to fulfill. This is true even of mercantile promises. No man is held to be under any moral obligation to pay his debts, any further than he has the means to pay; and upon giving up the property that he has, our insolvent laws will discharge him from the legal obligation. A promise to marry carries with it the implied reservation that he who promises shall continue to love. The promise is not, and is not understood to be, either by him who makes, or her who receives it, a promise merely to assume the legal responsibility of marriage; it is a promise to assume the moral and sentimental responsibilities also; and if, by change of circumstances or change of mind, it has become impossible to fulfill one part of the promise, if it is impossible to love. the whole necessarily falls to the ground.

What is the object and intent of that intimacy called an engagement of marriage, unless to enable the parties to live together in that freedom of intercourse which the mutual expectation of marriage inspires, for the very purpose of giving them an insight they would not otherwise have into each other’s character, and an opportunity of repentance and retraction before taking the irrevocable step? And if this be the object of an engagement—as who will venture to say it is not—how absurd to hold a man bound to marry, by the very process of socking to discover whether it will be judicious for him to marry or not?

Of all miserable things in this world of misery, a miserable marriage is the most miserable, yet every acute observer must have noticed that the misery of many of these marriages arises from causes too immaterial, so to speak, too spiritual to attract the notice of the casual observer. At a time when our courts and our legislatures are besieged by wives and husbands struggling to get rid of uncongenial partners; when the laws on the subject of divorce are loudly complained of in so many quarters, as failing to afford that relief which they ought, one measure, it would seem, might suit equally well both the friends and the enemies of the freedom of divorce. An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. It may be necessary to allow those married persons to separate, who have become not merely tiresome, but hateful to each other; but how much better to avoid the blunder of bringing such people together? Divorce at the pleasure of either party, after the marriage has been consummated, and especially after children are born, is limited to some very weighty objections; but what can be the objection to allowing the freedom of separation in cases where no marriage has yet been celebrated? If, indeed, to seek the intimacy of a lady with a view to discover if she is fit to be your wife, is to carry with it the obligation to make her so, at all events, we are in no respect better off than the Chinese, who marry their wives without over having seen them. So far, indeed, as the wife’s person is concerned, we have an advantage over the Chinamen, in the privilege of seeing so much of it as she exhibits to the world at large in the street, or as she displays to a select circle in a ballroom. Looks, however, in this climate, are not much to be depended upon. American beauty fades with marvellous rapidity; while, as to the lady’s temper, and mental and moral traits, which in our state of civilization are of at least equal importance with her face, if we are so impertinent as to peep into them, the law and public opinion insist that in so doing we have contracted an obligation to marry her. Thus, in fact, we are worse off than the Chinaman. He, if not suited with one wife, can take another, and so on, till he is suited. We, when once married, are done for. We can neither get rid of our uncongenial wife nor take a congenial one. Under these circumstances, we ought at least to have the privilege of making a choice with our eyes open, and not be held by the very act of examination to have precluded ourselves from declining to accept an article, which, however taking it might seem at first sight, proves, on being more closely looked at, not what we wanted.

[“A Word For Men’s Rights.” Putnam’s Monthly, A Magazine of Literature, Science , and Art, Vol. II, Feb. 1856, No. XXXVIII, p. 208]

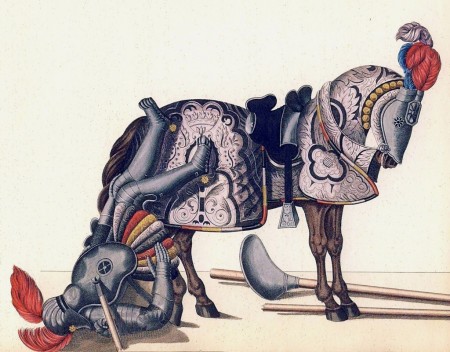

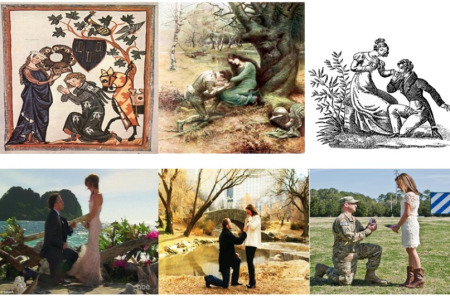

Caballeros Blancos (=caballeros blancos). Conservamos esta metáfora para estos heroicos individuos, hombres galantes de muchas maneras, pero especialmente las incorrectas, como alardear ante mujeres poco merecedoras y deleitarse de manera concomitante en competir y lastimar a otros hombres. Más que cualquier otro actor en esta obra, los caballeros blancos se especializan en el comportamiento galante con el propósito de impresionar a las mujeres, y lograr al final que estas les alimenten el ego.

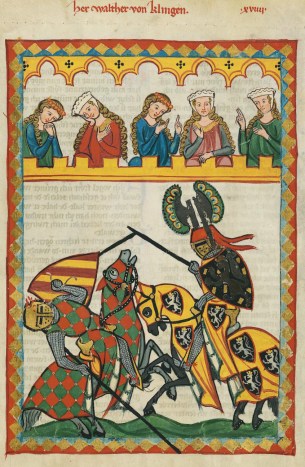

Caballeros Blancos (=caballeros blancos). Conservamos esta metáfora para estos heroicos individuos, hombres galantes de muchas maneras, pero especialmente las incorrectas, como alardear ante mujeres poco merecedoras y deleitarse de manera concomitante en competir y lastimar a otros hombres. Más que cualquier otro actor en esta obra, los caballeros blancos se especializan en el comportamiento galante con el propósito de impresionar a las mujeres, y lograr al final que estas les alimenten el ego. Otras actividades de los caballeros blancos incluyen impresionar mujeres con grandes gestos de protección. Por ejemplo, la “Empresa del Escudo Verde con la Dama Blanca” era una orden de caballería fundada por Jean Le Maingre y doce caballeros más en 1399 que se comprometían a proteger mujeres. Inspirados por el ideal del amor cortés, el propósito de la orden era proteger y defender el honor, los bienes, la propiedad, la reputación, la fama y el elogio de todas las damas y damiselas, una tarea que recibió el elogio de Christine de Pizan. Le Maingre, cansado de recibir quejas de damas, doncellas, y viudas quejándose de ser oprimidas por hombres poderosos empeñados en privarlas de tierras y honores, y de no encontrar caballero o escudero dispuesto a defender su justa causa, fundó la orden de doce caballeros jurados a llevar “un escudo de oro esmaltado de verde y con una dama blanca en su interior.”

Otras actividades de los caballeros blancos incluyen impresionar mujeres con grandes gestos de protección. Por ejemplo, la “Empresa del Escudo Verde con la Dama Blanca” era una orden de caballería fundada por Jean Le Maingre y doce caballeros más en 1399 que se comprometían a proteger mujeres. Inspirados por el ideal del amor cortés, el propósito de la orden era proteger y defender el honor, los bienes, la propiedad, la reputación, la fama y el elogio de todas las damas y damiselas, una tarea que recibió el elogio de Christine de Pizan. Le Maingre, cansado de recibir quejas de damas, doncellas, y viudas quejándose de ser oprimidas por hombres poderosos empeñados en privarlas de tierras y honores, y de no encontrar caballero o escudero dispuesto a defender su justa causa, fundó la orden de doce caballeros jurados a llevar “un escudo de oro esmaltado de verde y con una dama blanca en su interior.”

Es sencillo exagerar la importancia de los ejemplos específicos de ginocentrismo cuando en realidad dichos ejemplos pueden estar igualmente balanceados, culturalmente hablando, por actos y costumbres centrados alrededor de los hombres, o por eventos que niegan el concepto de una ubicua cultura ginocéntrica. Se nos recuerda aquí que el viejo adagio “

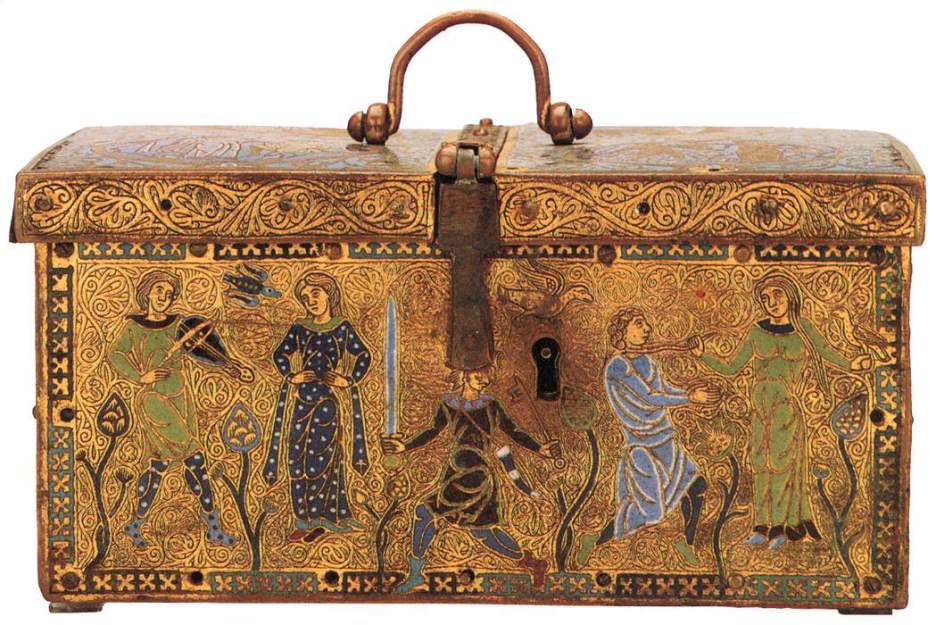

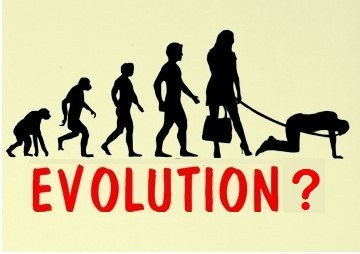

Es sencillo exagerar la importancia de los ejemplos específicos de ginocentrismo cuando en realidad dichos ejemplos pueden estar igualmente balanceados, culturalmente hablando, por actos y costumbres centrados alrededor de los hombres, o por eventos que niegan el concepto de una ubicua cultura ginocéntrica. Se nos recuerda aquí que el viejo adagio “ La feudalización del amor no era algo que pudiera verse en épocas anteriores al Medioevo, y mucho menos en la era Paleolítica cuando el feudalismo sencillamente no existía. Por ejemplo, no hemos visto aún pinturas en cuevas iguales a este arte de la Edad Media que muestra a un hombre actuando como servil vasallo de una mujer dominante, quien lo lleva de su cuello por un cabestro.

La feudalización del amor no era algo que pudiera verse en épocas anteriores al Medioevo, y mucho menos en la era Paleolítica cuando el feudalismo sencillamente no existía. Por ejemplo, no hemos visto aún pinturas en cuevas iguales a este arte de la Edad Media que muestra a un hombre actuando como servil vasallo de una mujer dominante, quien lo lleva de su cuello por un cabestro.