The following article appeared in the Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser – Friday 24 April 1914

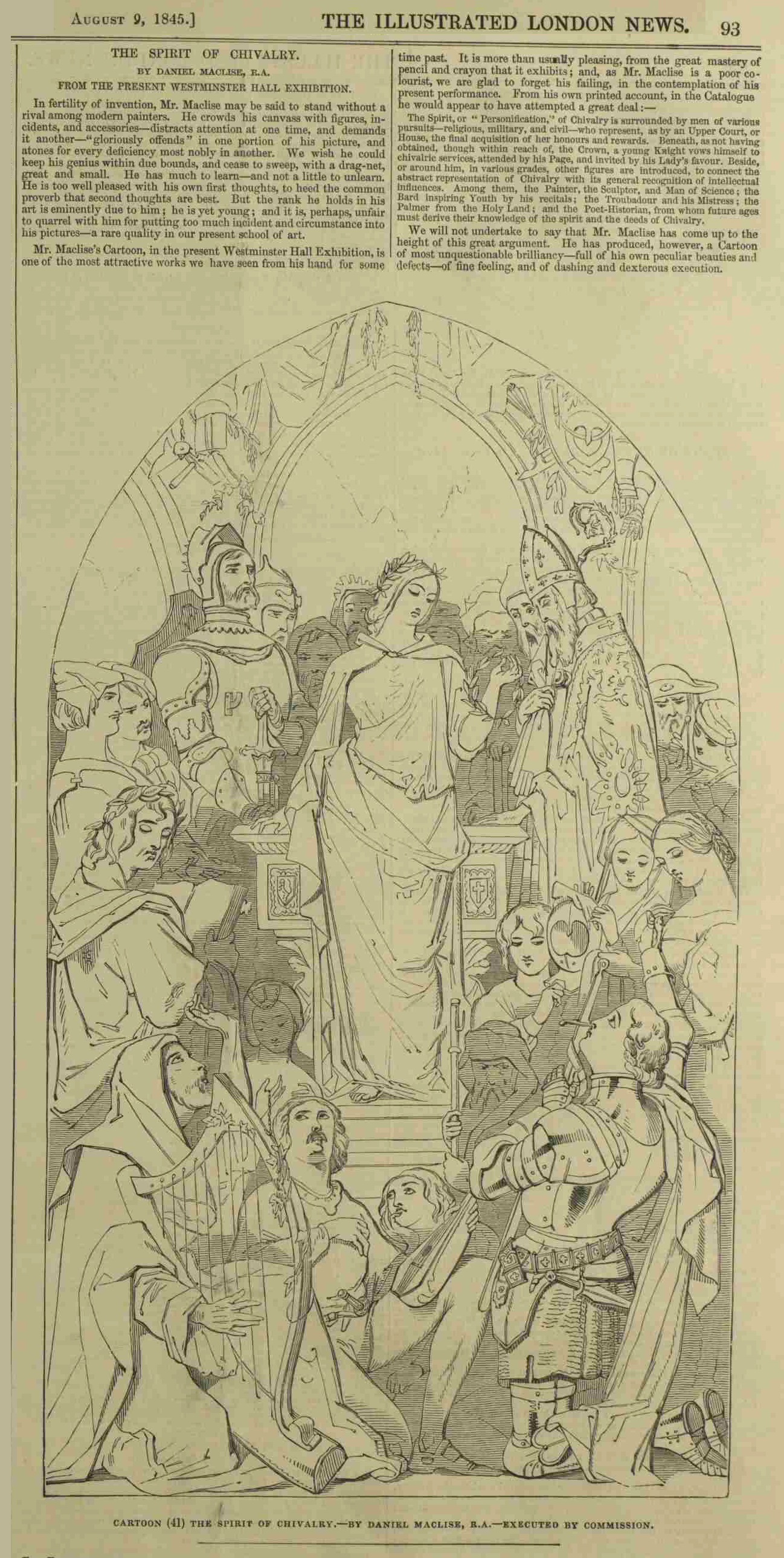

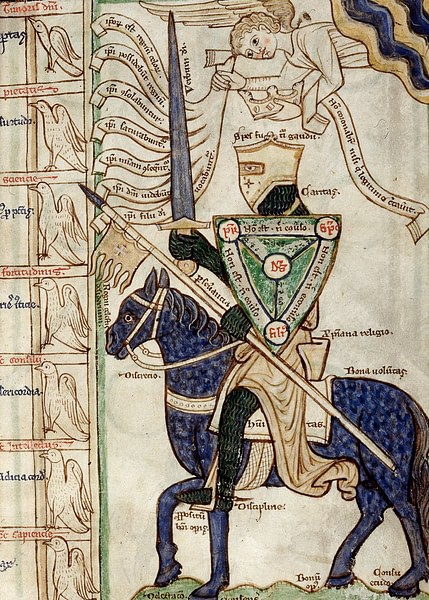

The following graphic depicting the spirit of chivalry was exhibited in Westminster Hall, London, in August 1845. The author of this image describes the scene as follows:

The spirit, or “personification” of Chivalry is surrounded by men of various pursuits — religious, military, and civil — who represent, as by an Upper Court, or House, the final acquisition of her honours and rewards. Beneath, as not having obtained, though within reach of the Crown, a young Knight vows himself to chivalric services, attended by his Page, and invited by his Lady’s favour. Beside, or around him, in various grades, other figures are introduced to connect the abstract representation of Chivalry with its general recognition of intellectual influences. Among them the Painter, the Sculptor, the Man of Science; the Bard inspiring Youth by his recitals; the Troubadour and his Mistress; the Palmer from the Holy Land; and the Poet-Historian, from whom future ages must derive their knowledge of the spirit and the deeds of Chivalry.

The spirit, or “personification” of Chivalry is surrounded by men of various pursuits — religious, military, and civil — who represent, as by an Upper Court, or House, the final acquisition of her honours and rewards. Beneath, as not having obtained, though within reach of the Crown, a young Knight vows himself to chivalric services, attended by his Page, and invited by his Lady’s favour. Beside, or around him, in various grades, other figures are introduced to connect the abstract representation of Chivalry with its general recognition of intellectual influences. Among them the Painter, the Sculptor, the Man of Science; the Bard inspiring Youth by his recitals; the Troubadour and his Mistress; the Palmer from the Holy Land; and the Poet-Historian, from whom future ages must derive their knowledge of the spirit and the deeds of Chivalry.

By Vernon Meigs

In light of the trend of transgender mania and woke and politically correct culture, those on the conservative traditionalist side are keen on throwing around terms like “gender cult.” This gender cult they speak of is that of gender subjectivism, denial of organic attributes of sex, and divorcing the metaphysical and behavioral aspects of sex from the biological real-world component – what progressives would like to call sex assigned at birth.

It’s not that they’re necessarily wrong here, calling this a gender cult. It is; albeit a specialized reactionary one that professes to rebel against gender norms. Ironically enough transgender identity relies on stereotyped ideas about gender to then say they are defying it.

What I want to address is the idiocy of those who claim to be fighting this gender cult, namely the hypocrisy of calling it a gender cult when they as neotraditionalists are likely to indulge and take for granted a gender cult of their own, one which is more massive and has a bigger, more longstanding history than even feminism itself.

Gynocentrism and gyneolatry contain qualities in every way attributable to an actual gender cult. The fact that it actually gave way to feminism, which in turn gave way to political transgender ideology, is evident but conveniently ignored too often by these conservatives. They don’t want to address it because, as practitioners of the gynocentric gender cult, they either are dependent on it to keep the approval of the women in their immediate lives as well as from the public, or suffer from a serious normalized case of Stockholm Syndrome.

Anyway, to the heart of the subject of this article: The gender cult that the traditional conservative promotes and refuses to denounce.

Men are expected to die in wars while the royal class of women are subject to protection by these men. That is a gender cult.

Men are expected, from the point of courtship til well after the divorce, to financially and in effect materially provide for womankind. That is a gender cult.

Men are expected at one day old to have a crucial component of their genitalia ripped off, despite the risk of infection, physical complications that follow, and death, as well as guaranteed psychological trauma manifesting itself at varying degrees later in life — apparently for the sake of anywhere from Sandra Bullock’s, Oprah’s, and Kate Beckinsale’s facial creams to the depraved whims of women sexually attracted to broken manhood. That is a gender cult. Circumcision of baby boys is a gender cult.

Women are regarded as equivalent of nature, designated as the big choosers, and the men as vassals that must commit degrading acts of altruism to earn their attention, this despite the fact that men and women are both choosers and members of nature together. This one-sided attitude is a gender cult.

Families, in particular in North America, favor supporting daughters after adulthood, whereas men are generally kicked out of the house when they reach the age of 18, expected to fend for themselves because “a man should take care of himself” else he gets shamed as a dweller in his parents’ basement with no life. Women categorically reject men at the slightest hint of them receiving assistance in any such way in the dating market, for instance. I call that a gender cult.

To engage in romance a man must first place himself in a position of self-degradation of bending his knee in front of a woman and present her with a hunk of rock, which may or may not be a blood diamond, that he has spent a ridiculous amount of his fortune on. That’s the first edge. What is either a curt rejection and no further regard by the woman for the trouble the man went through or, if she did accept, then the wedding will be even more of a fortune lost on the man’s part and it will be again when the divorce follows, which happens at this point too often to not consider it an event to expect, and practically schedule. Either way, royal woman looks down at vassal man. That is the image of the man going down on his knee and proposing. That is a gender cult.

Violence against men, especially by women, is subject to laughter. The very act of entertaining the idea of violence against women, especially by men, is grounds for ostracism at best, violent retribution at worst. Self-defense is not tolerated even if the man is faced with a rabid crazed blade wielding unhinged psycho woman on a rampage. That is a gender cult.

Happy wife, happy life. If Momma ain’t happy, ain’t nobody happy. Placing women on status of maniacal ruler whose whims must be satisfied else the man’s existence is not justified. That is a gender cult.

To the traditional conservatives out there, and anyone who professes to ally with feminists and other misandrists just so they could own the trans gender cult — this discussion is for you. The gender cult which you profess to wage war on is but a fad compared to the grander gender cult that is gynocentrism that you take for granted and bask in.

I’ll close with something that I want you to get through to your head. Gynocentrism is a gender cult. It is the biggest such cult. Gyneolatry is woman-worshipping in this gender cult. Biogynocentrism is the means of rationalizing it with the alleged argument from biology and evolution in this gender cult. Male disposal is the end goal of this gender cult. Gynocentrism is a gender cult.

The following excerpts are from David L. Miller’s 1991 essay Why Men Are Mad: Nothing Envy and The Fascration Complex. At a time when multiple sexualities are now topical, including transgendered identities, Miller’s essay provides an imaginative springboard for contemporary audiences. In this article Miller emphasizes men’s adherence to ‘patriarchal’ fantasies while simultaneously harboring a wish to be free of same, and while ‘patriarchy theory’ was a feminist invention of 1980s-90s when the author penned these thoughts (now considered an imaginary artifact that holds questionable explanatory power), the essay itself contributes new and complimentary layers to Freud’s ‘penis envy’ theory. He does this by posing that men, too, may envy the un-membered state of womanhood. Whether this perspective aids in better understanding the dynamics of transgender and other sexualities will be left to the imagination of the reader.

________________________________________________________________________

By David L. Miller

One clue to the hurt men feel, to their crazy rage, can be discerned in an essay entitled “Some Psychical Consequences of the Anatomical Distinction Between the Sexes” (1925), where Freud describes a traumatic moment of childhood, the discovery of penis envy. The little girl “has seen it and knows that she is without it and wants to have it” (252).

But, according to Freud, the little boy’s experience, or at least the screen-memory of the experience, is different. Only later when confronted with the threat of castration does the boy or man recall the sight of the little girl. Then he knows of the real possibility of losing a part of his body. There arises an anxiety — the so-called “castration complex” — together with two possible reactions to women: either “horror of the mutilated creature” or “triumphant contempt for her” (Freud, 1961: 252; 1959; 1964b; Du Bois: 10-11). The neurotic consequence of childhood trauma for the woman is envy and inferiority; for the man, anxiety and superiority.

There is an asymmetry in Freud’s theory. Why has he not moved to observe envy in the man as in the woman, and anxiety in the woman as in the man? Is there no complex in the woman to correspond to castration in the man? And is there no envy in the man to correspond to the envy for the penis in the woman?

A few theorists and therapists have wondered about these questions. Bruno Bettelheim thought that “penis envy in girls and castration anxiety in boys have been over-emphasized” by psychoanalysis, and that there is “a possibly much deeper psychological layer in boys that has been relatively neglected.” He called this deeper matter “vagina envy” (20). Karen Horney, also, has spoken of a “femininity complex” in men and has raised the question of “why no corresponding impulse to compensate herself for her penis envy is found in women” (61; also 21, 60). But in this theorizing, the envy noted in the male has to do with the woman’s ability to bear children, “pregnancy envy,” as Eric Fromm calls it (233). This focuses on only one aspect of woman, an aspect which a patriarchal tradition is eager to totalize.

* * *

If the little girl sees something, and then envies this thing, one could say that the little boy sees nothing and envies that nothing. The traumatic physical moment produces psychological “nothing-envy.” Nothing-envy is the desire lurking as the diabolical other-side of the castration anxiety. The fundamental ambivalence of the psyche demands that a person face the two-sidedness of fear. There is a latent wish in the symptom of anxiety. Castration is what a man wants as well as what he most fears. What does a man want? Nothing.

* * *

Similarly, men have no desire to be deprived of their penises. This is not what nothing-envy is about. The penis, besides being an efficient piece of plumbing, gives a good deal of pleasure. But the phallus is a different thing. The very patriarchy which has connected dominance, power, aggression, initiative, rational meaning, thinking and commitment to maleness, that perspective which has deprived women of a phallus, has also loaded more on men than they wish to bear. What a relief it would be to be rid of this thing, to have nothing.

Ernest Wallwork has called my attention to evidence of this nothing-envy in men. A bit of play familiar to all men from their days in school locker rooms is that of pulling the penis back and holding it between one’s legs so that one looks like a woman. The play is the symptom of a wish. The little boy looking upon the little girl in wonder experiences both fear and desire. The trauma produces not only a castration complex but also nothing-envy. Mysterium Tremendum et fascinosum: I am afraid of nothing, of losing something, and, at the same time, I am drawn to nothing. Freud noticed the former, but he missed the latter.

* * *

There is a long litany of female affirmations of women’s weavings, and they have little or nothing to do with envy of men. Rather, these testimonies and expressions have deep archetypal rooting in Athena and Arachne, in Persephone, in Philomela, and in Charlotte’s Web (see Gubar: 74, 89, 91). What is the missing female complex to which weaving points? I propose to name it “the fascration complex,” drawing upon a Mediterranean word having to do with weaving. Fasces is a bundle of twigs woven together, a bit of wicker work, the work of the wicca (who is by no means a witch). The term fasces gives us our word “basket,” as well as “fasten,” “fascination,” and “fascist.”

What the little boy sees when he gazes upon what is non-a-thing is the female “basket” and later he will come to admire the webs and tapestries a woman can weave with it. She is anxious about losing her basket, her weaving, her fasces, for this, not the penis, is her power.

* * *

An erotics of male desire discloses a projection of a wish based on lack… a lack of nothing. It is a desire for nothing because men ‘don’t got plenty of nothing.’ The irony, of course, is that that is exactly what they have plenty of — which is why they are mad. The return of the repressed is the return of something that never went away. A man never did not have nothing. If a man could withdraw his projection onto women of nothing, he could be who he is, one-in-himself, male and female, something and nothing. There is nothing of which to be envious. We are always and already nothing.

* * *

Why Men Are Mad: Nothing–Envy and the Fascration Complex, by David L Miller, Spring Journal 51, Spring: Dallas, 1991. [FULL TEXT pdf made available by permission of the author].

Below is an amended excerpt from an interview with Greta Aurora which touches on archetypes of masculinity and femininity appearing in traditional mythologies.

Greta Aurora: You previously mentioned you don’t agree with looking at masculinity and femininity as the order-chaos duality. Is there another archetypal/symbolic representation of male and female nature, which you feel is more accurate?

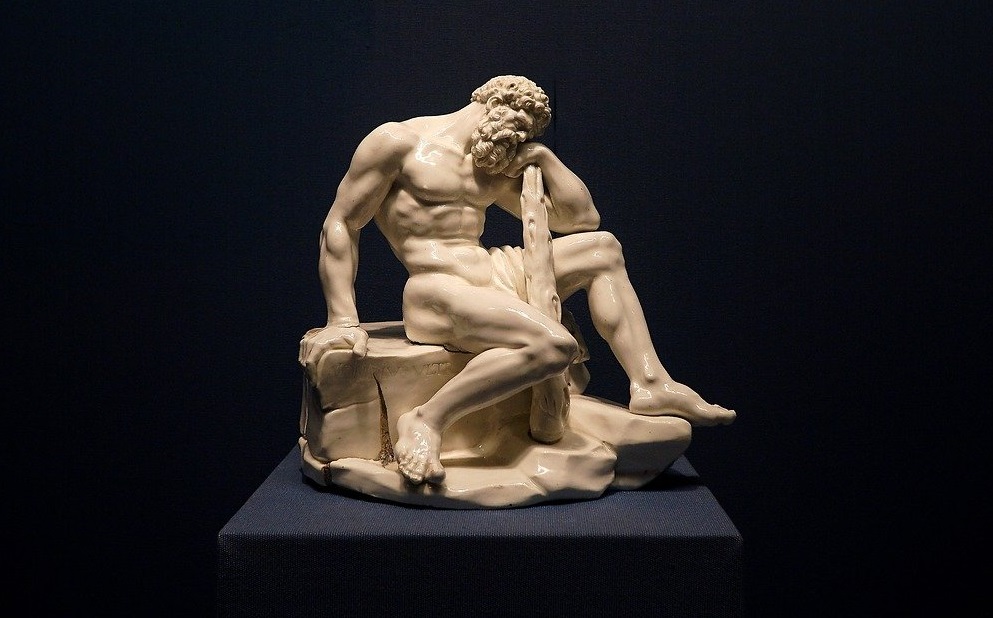

Peter Wright: Some archetypal portrayals in mythology are distinctly male and female, such as male muscle strength and the various tests of it (think of the Labours of Hercules), or pregnancy and childbirth for females (think Demeter, Gaia etc.). Aside from these universal physiology-celebrating archetypes, many portrayals of male or female roles in traditional stories can be viewed instead as stereotypes rather than archetypes in the sense that they are not universally portrayed across different mythological traditions (as would be required of a strictly archetypal criteria in which images must be universally held across cultures).

For example you have a Mother Sky and a Father Earth in classical Egyptian mythology, which is a reverse of popular stereotypes, and males are often portrayed as nurturers. This indicates that material nurture is not the sole archetypal province of a feminine archetype. Also, many archetypal themes are portrayed interchangeably among the sexes – think of the Greek Aphrodite or Adonis both as archetypal representations of beauty, or Apollo and Cassandra as representatives of intellect, or of the warlikeness to Ares or Athene.

To my knowledge the primordial Chaos described in Hesiod’s Theogony had no apparent gender, and when gender was assigned to Chaos by later writers it was often portrayed as male. There is no reason why we can’t assign genders to chaos and order to illustrate some point, but we need to be clear that this rendition is not uniformly backed by archetypal portrayals in myths – and myths are the primary datum of archetypal images. So broadly speaking the only danger would be if we insist that chaos must always be female, and order must always be male as if that formula were an incontrovertible dogma.

There’s also a rich history of psychological writings which look at chaos as a state not only of the universe, or of societies, but as a potential in the psyche or behavior of all human beings regardless of gender; e.g. this factor elaborated for example in the writings of psychiatrists R.D. Laing and by W.D. Winnicott .

Courtly Love (Amour Courtois) refers to an innovative literary genre of poetry of the High Middle Ages (1000-1300 CE) which elevated the position of women in society and established the motifs of the romance genre recognizable in the present day. Courtly love poetry featured a lady, usually married but always in some way inaccessible, who became the object of a noble knight’s devotion, service, and self-sacrifice. Prior to the development of this genre, women appear in medieval literature as secondary characters and their husbands’ or fathers’ possessions; afterward, women feature prominently in literary works as clearly defined individuals in the works of authors such as Chretien de Troyes, Marie de France, John Gower, Geoffrey Chaucer, Christine de Pizan, Dante Alighieri, Giovanni Boccaccio, and Thomas Malory.

Scholars continue to debate whether the literature reflected actual romantic relationships of the upper class of the time or was only a literary conceit. Some scholars have also suggested that the poetry was religious allegory relating to the heresy of the Catharism, which, persecuted by the Church, spread its beliefs through popular poetry while others claim it represents superficial games of the medieval French courts. No consensus has been reached on which of these theories is correct, but scholars do agree that this kind of poetry was unprecedented in medieval Europe and coincided with an idealization of women. The poetry was quite popular in its time, contributed to the development of the Arthurian Legend, and standardized the central concepts of the western ideal of romantic love.

Courtly love poetry emerged in southern France in the 12th century CE through the work of the troubadours, poet-minstrels who were either retained by a royal court or traveled from town to town. The most famous of the early troubadours (and, according to some scholars, the first) was William IX, Duke of Aquitaine (l. 1071-1127 CE), grandfather of Eleanor of Aquitaine (l. c. 1122-1204 CE). William IX wrote a new kind of poetry, highly sensual, in praise of women and romantic love. William IX and the troubadours who followed him never referred to their work as courtly love poetry or Provencal love poetry – it was simply poetry – but it was unlike any literature produced in Western Europe previously. Scholar Leigh Smith discusses the origin of the name:

The term itself dates back only to 1883 CE when Gaston Paris coined the phrase Amour Courtois to describe Lancelot‘s love for Guinevere in the romance Lancelot (c. 1177 CE) by Chretien de Troyes. Medieval literature employs a variety of terms for this kind of love. In Provencal the word is cortezia (courtliness), French texts use fin amour (refined love), in Latin the term is amor honestus (honorable, reputable love). (Lindahl et. al., 80)

This love praised by the troubadours had nothing to do with marriage as recognized and sanctified by the Church but was extramarital or premarital, freely chosen – as opposed to a marriage which was arranged by one’s social superiors – and passionately pursued. An upper-class medieval marriage was a social contract in which a woman was given to a man to further some agenda of the couple’s parents and involved the conveyance of land. Land equaled power, political prestige, and wealth. The woman, therefore, was little more than a bargaining chip in financial and political transactions.

In the world of courtly love, on the other hand, women were free to choose their own partner and exercised complete control over him. Whether this world reflected a social reality or was simply a romantic literary construct continues to be debated in the present day and central to that question is the figure of Eleanor of Aquitaine.

As with many aspects of the discussion of courtly love, Eleanor’s role in developing the concept remains controversial. Eleanor of Aquitaine was one of the most powerful women of the Middle Ages, wife of Louis VII of France (r. 1137-1180 CE) and Henry II of England (r. 1154-1189 CE), and mother of Marie de Champagne (l. 1145-1198 CE) from her marriage to Louis and Richard I (r. 1189-1199 CE) and King John (r. 1199-1216 CE) from her marriage to Henry. She had eight children in total with Henry II, most of whom would follow her example in patronizing the arts.

Throughout her marriage to Louis VII (1137-1152 CE), Eleanor filled her court with poets and artists. When their marriage was annulled in 1152 CE, Eleanor did the same at her own court in Normandy, where she was especially entertained by the young troubadour Bernard de Ventadour (12th century CE), one of the greatest medieval poets, who would follow her to the court of Henry II in 1152 CE and remain with her there three years, probably as her lover.

Louis VII, after Eleanor’s departure, drove the troubadours from his court as bad influences, and Henry II seems to have had an equally low opinion of the poets. Eleanor admired them, however, and when she separated from Henry II in c. 1170 CE and set up her own court at Poitiers, she again surrounded herself with artists. There is no doubt that she inspired the works of Bernard de Ventadour, but it is likely she did the same for many others and, through her daughter Marie, inspired the greatest and most influential works of courtly love literature.

Eleanor’s court at Poitier, c. 1170-1174 CE, is a subject of some controversy among modern-day scholars in that no consensus has been reached as to what went on there. According to some scholars, Marie de Champagne was present while others argue she was not. Some scholars claim that actual courts of love were held there with Eleanor, Marie, and other high-born women presiding over cases in which plaintiffs and defendants would present evidence relating to their romantic relationships; others claim no such courts existed and that any literature suggesting they did is satire.

THE BEST-KNOWN EXAMPLE OF COURTLY LOVE IS LANCELOT’S LOVE FOR GUINEVERE, THE WIFE OF HIS BEST FRIEND & KING, ARTHUR OF BRITAIN.

Whatever happened at Poitiers, Eleanor seems to have established the ground rules for a literary genre – and possibly a social game of sorts – which was then developed by her daughter who was the patroness of the poet Chretien de Troyes (l. c. 1130-1190 CE) and author Andreas Capellanus (12th century CE). Andreas is the author of De Amore (usually translated as The Art of Love) which describes the courts of love presided over by Marie and the others while also serving as a kind of manual in the art of seduction.

The work draws on the earlier satirical Art of Love (Ars Amatoria) of Ovid, published c. 2nd century CE, which presented itself as a serious guide to romantic relationships while actually mocking them and anyone who takes such things seriously. Since Andreas’ work so closely mirrors Ovid’s, some scholars claim that it was written for the same purpose – as satire – while others accept it as a serious guide to navigating the world of courtly love. Andreas set down the four rules of courtly love as, allegedly, derived from Eleanor and Marie’s courts:

According to these rules, just because one was married did not mean one could not find love outside of that contract; love was expressed most clearly through jealousy which proved one’s devotion; there was only one true love for every individual and no one could honestly claim to love two people the same way; true love was never static but always dynamic, unpredictable, and ultimately unknowable even by those experiencing it because it was initiated and directed by a God of Love (Cupid), not by the lovers themselves. These concepts in Andreas’ prose work were mirrored in Chretien’s poetry.

Chretien de Troyes is the poet responsible for some of the best-known aspects of the Arthurian Legend including Lancelot’s affair with Guinevere and the Grail Quest. His works include Erec and Enide, Cliges, Lancelot or the Knight of the Cart, Yvain or the Knight of the Lion, and Percival or the Story of the Grail, all written between c. 1160-1190 CE. Chretien established the central motifs of the genre of courtly love poetry which include:

The best-known example of this is Lancelot’s love for Guinevere, the wife of his best friend and king, Arthur of Britain. Lancelot cannot deny his feelings but cannot act on them without betraying Arthur and exposing Guinevere as the unfaithful wife of a noble king. In Malory’s version of the legend, their affair’s exposure is pivotal in destroying the Knights of the Round Table. Another example is the famous story of Tristan and Iseult by Thomas of Britain (c. 1173 CE) in which young Tristan is asked by his uncle Mark to escort Mark’s fiancé Iseult to his castle. Tristan and Iseult fall in love (in some versions because of a love potion accidentally taken) and their betrayal of Mark is the plot point that drives the rest of the story.

Although scholars continue to debate Eleanor of Aquitaine’s role in developing these kinds of stories, even a cursory knowledge of the woman’s life strongly suggests that courtly love poetry was inspired by her. Like the lady character in the poems, Eleanor was never defined by either of her marriages, she always did precisely as she pleased except for the period in which Henry II had her imprisoned, and she inspired devotion in others. Eleanor’s role seems even more prominent if one entertains the theory that courtly love poetry was actually religious allegory depicting the beliefs of the heretical sect of the Cathars.

The Cathars (from the Greek for “pure ones”) were a religious sect which flourished in southern France – precisely in the regions of the courts of Eleanor and Marie – in the 12th century CE. The sect evolved from the earlier Bogomils of Bulgaria and adherents were popularly known as Albigensians because the town of Albi was their greatest religious center. The Cathars rejected the teachings of the Catholic Church on the grounds they were immoral and the clergy corrupt and hypocritical.

Catharism was dualist – meaning they saw the world as divided between good (the spirit) and evil (the flesh) – and the Church was decidedly on the side of evil as the clergy was more devoted to earthly pleasures than spiritual pursuits, and the dogma emphasized the weight of sin over the hope of redemption. Cathars renounced the world, lived simply, and devoted themselves to helping others. The Cathar clergy were known as perfecti while adherents were called credentes. A third set of people were the sympathizers – those who remained nominally Catholic but supported Cathar communities and protected them from the Church.

The Church suspected both Eleanor and Marie as sympathizers, and this suspicion was strengthened by the actions of Raymond VI, Count of Toulouse (r. 1194-1222 CE), Eleanor’s son-in-law, who was not only a Cathar sympathizer but secretly the Cathar bishop of his region. Raymond was the most ardent defender of the Cathars when the Church finally launched the Albigensian Crusade against Southern France in 1209 CE.

The correlation between Catharism, Eleanor, and courtly love poetry is that this genre seems to appear out of nowhere at the same time Catharism is flourishing and Eleanor is holding her courts. This theory (advanced, primarily, by the scholar Denis de Rougemont in his Love in the Western World), highlights how one of the main tenets of Catharism was recognition of the female principle in the divine which they recognized as the goddess Sophia (wisdom) and how the core of the belief was dualist. The theory then claims that courtly love poetry was an allegory in which the damsel-in-distress was Sophia, held captive by the Catholic Church, and the brave knight was the Cathar whose duty was to liberate her.

The lady symbolized good as spirit – and so the knight could never consummate his love for her – while the marriage she was trapped in, sanctified by the Church, symbolized the evil of the world. This theory is by no means universally accepted but it should be noted that there seems to be a direct correlation between the activities of the troubadours of southern France and the spread of Catharism in the 12th century CE.

Another theory (advanced by scholar Georges Duby, among others), is that courtly love was a medieval social game played by the upper-class in their courts. Duby writes:

Courtly love was a game, an educational game. It was the exact counterpart of the tournament. As at the tournament, whose great popularity coincided with the flourishing of courtly eroticism, in this game the man of noble birth was risking his life and endangering his body in the hope of improving himself, of enhancing his worth, his price, and also of taking his pleasure, capturing his adversary after breaking down her defenses, unseating her, knocking her down and toppling her. Courtly love was a joust. (57-58)

According to this theory, the lady in the tales serves “to stimulate the ardour of young men and to assess the qualities of each wisely and judiciously. The best man was the man who had served her best” (Duby, 62). This theory accounts for the misogynistic elements of courtly love poetry in that the woman is an object to be conquered sexually, not an individual, or is an arbiter of a man’s worth based solely on her status as noble and, again, not because of who she is as a person.

This aspect of the genre, however, may not be so much misogynistic as idealistic. If courtly love was a game invented by women, then woman-as-prize and woman-as-judge would have served the same purpose of elevating their status. Other scholars have pointed out that there were court games played by the upper class well into the Renaissance which would amount to role-playing and that the courts of love Andreas Capellanus describes were not actual courts but simply games the noble ladies created to amuse themselves; the works of Andreas and Chretien and others just added to the enjoyment or provided ground rules. Leigh Smith writes:

As with any game that depends upon the creation of an alternate reality, the fun depends upon all the participants treating that reality with utmost seriousness. Therefore, Andreas’ treatise may be understandable as a guide to being a successful courtier in such a Court of Love. (Lindahl et. al., 82)

The winner in this game would be the knight who exemplified the virtues of chivalry and courtesy in service to his lady. It is possible these games were played over the course of months – and perhaps that is what was happening at Eleanor’s court at Poitiers c. 1170-1174 CE – but the game theory does not explain the passion of the works themselves, the devotion the knight has to the lady, or their enduring popularity. Most importantly, the game theory does not fully explain why, even if women invented the game, they should suddenly be so elevated in this genre in a way no earlier European literature had done.

The genre was considered completely original by scholars of the 19th and 20th centuries CE who, while recognizing the central motif of the elevation of the lady present in some Roman works and the biblical Song of Songs, had little or no knowledge of the literature of ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt. As noted, ‘courtly love’ was coined by French writer Gaston Paris only in 1883 CE, and the concept was not fully developed until 1936 CE by C. S. Lewis in his Allegory of Love.

These authors were both writing at a time when the understanding of Egyptian hieroglyphics (in Paris’ case) and Mesopotamian cuneiform (for Lewis) was in relative infancy. Many works, from both ancient cultures, had yet to be translated – most famously, The Love Song for Shu-Sin (c. 2000 BCE) from Sumer, considered the world’s oldest love poem, which was not translated until 1951 CE by Samuel Noah Kramer. Works from both cultures that had been translated were not often widely publicized outside of anthropological circles.

Accordingly, writers like Paris and Lewis interpreted the literature of courtly love as something unprecedented in world literature when, actually, it was not; it was simply new to medieval Europe. The Egyptian and Mesopotamian cultures both regarded women highly, and their literature bears witness to that. Somehow, whether as religious allegory or role-playing or simply through the efforts of one woman, the poets of Southern France – with no knowledge of the passionate poems of Mesopotamia or Egypt – produced the same sort of literature in a culture which did not support that vision. Women were consistently devalued and denigrated throughout most of the Middle Ages but, in the poetry of courtly love, they reigned supreme.

Joshua J. Mark (published 2019)

A freelance writer and former part-time Professor of Philosophy at Marist College, New York, Joshua J. Mark has lived in Greece and Germany and traveled through Egypt. He has taught history, writing, literature, and philosophy at the college level.

Creative Commons reprint.

By Raymond J. Cormier

While the influence of powerful troubadour motifs is undeniable, let us cite here one brief northern French text as a kind of shorthand, for emphasis. It is a brief narrative or lai that illustrates certain courtly values. Lanval, Marie de France’s eponymous hero, is a sad, forlorn Arthurian knight, abandoned, lonely, and helpless. An otherworldly sequence brings to him a wealthy and supremely stunning noblewoman (a fairy princess) with whom he becomes “well lodged.”

His liberation from the bonds of solitary abandonment lead to liberality (he now gives freely to all comers), the medieval ideal of generosity, “the queen of virtues.”9 Kindness and love rescue him, as they do several male characters in modern film.10 Northern French poets emphasized too the “chivalry topos,” that is, that love motivates the knight in love and he becomes a better person through his adventures, thus meriting his beloved all the more. Noble love ennobles; in this better world too (for Auerbach), the apolitical “feudal ethos” encompasses “self-realization” (116-117).

Courtly thinking existed in the Middle Ages and is manifested in the modern era.11 Each of the films we analyze here will of course not yield up every feature of the courtly mode, but still I sense that there is enough medieval residue and resonance in each to justify the argument, that, as some might put it succinctly, “courtly themes continue to generate artistic creation.” Along these lines, one wonders if the strong continuity of the Troubadour ethos—in particular that longing for a “far-away love”—is what underlies the resonances and residues. Love stories, requited or not, remain viable even in today’s hip-hop world.

It has been reasoned that the two principal and most admired modes of courtly behavior were generosity and joy. Aristocratic courtly culture held that “the lady” was lord, and the lover’s role was to serve her, to sing about her merits and qualities, and carry out all imaginable actions to remain or become worthy of her, in a word, to deserve her.12

The function of love in this context was as dictated by the De amore of Andreas Capellanus (ca. 1185): “Love easily attained is of little value; difficulty in obtaining it makes it precious” and “Everything a lover does ends in the thought of the beloved.”13

For Auerbach, the synthetic term corteisie embodied values like the “refinement of the laws of combat, courteous social intercourse, service of women” (117). In what is dubbed the long European twelfth century (1050-1250), French humanism predominated, a phenomenon already analyzed historiographically at length.

As Italianist Ronald Witt recently put it (2012: 317): “The term ‘humanism’ aptly describes French culture in the period […].” In this context, interior monologue and dialogue arose from a new awareness of the interior life (the unique individual is now consciously separate from the court), which was further linked to the chivalric adventure/quest whereby audiences yearned for the unusual and the marvelous—now stimulated especially by wondrous stories brought back from the East by returning Crusaders (in particular the First-ca. 1100, and Second-ca. 1150). In discussing this particular type of medieval love, Aldo Scaglione has written (559):

The radical interiorization of the love experience carried with it the impossibility of communicating with the love object (topos of ineffability). Not only did poets profess themselves incapable of communicating to the beloved the depth of their passion, but the very lack of communication was for them both a sign of its depth and a consequence of it, to the point of entailing the complete physical absence of the lady.

Transformation through kindness and love, the frequent quest motif, the rescue of the hero/heroine—such are the narrative innovations associated with these elements (even the ineffable moment can be noted in at least one film, Roxane). Allied terms include honesty and humility—for perfection of the knight depended on his courtly worth, manifested through continuous bravery and feats of arms, humbly accomplished so to enhance and vouchsafe his honor and his nobility.

Such aims for flawlessness were mirrored by the lady’s perfection, inspired too by her knight/liege. Of course, adultery occurs as co-incidental in this context, as does a “religion of love,” whereby mutual suffering and adoration are obligatory14. Let us see how all this plays out in the series of films selected for analysis.

As Good As It Gets

The romantic comedy As Good As It Gets, the Jack Nicholson and Helen Hunt masterpiece (with Greg Kinnear), has provided the main title of this essay. The iconic line, “You Make Me Want to Be A Better Man,” is spoken by the misanthropic Melvin Udall (Jack Nicholson), whose obsessive-compulsive behavior and pathological germophobia strangle all of his human interactions. In the penultimate sequence, after he affronts and insults Carol (played by Hunt), his apology, necessary to get back into her good wishes, is a confession that he wants to merit her and deserve her respect (enough so that he can have their relationship return to its prior arrangement).

One can say that all his motivations are selfish (arranging to care for Carol’s asthmatic son, putting up with his gay artist neighbor and then the neighbor’s dog), yet he is redeemed in the end, having moderated somewhat his odd manners.15 If not mere empathy, a kind of love is born in Melvin’s heart—even for his gay neighbor, for the dog, even for his neighbor’s African-American agent, and especially for Carol. For in the end, he is “a better man.”

Pretty Woman

Perhaps no genuinely touching and dreamlike modern film has captioned courtly features as much as Pretty Woman (1990), in which the Richard Gere character (Edward) undergoes a major personality shift, from ruthless business tycoon to generous shipbuilder, as a result of his experience of love for/with (an apparently) blonde streetwalker named Vivian (played by Julia Roberts).16 The wig disguises, as it were, her true personality. Over and above the film’s obvious Cinderella theme, it has been argued in fact, in a reversal of traditional gender roles, that it is she, Vivian, who, as the “Fair Unknown” (Scala 35), is transformed from “veiled” Hollywood Boulevard prostitute into a truly “noble character,” a change attributable to soul-sharing (with Edward—neither “wimp nor wild man”17), catalyzed by the experience of a San Francisco opera performance focused on the heroine Violetta (La Traviatta).

Vivian’s real character is revealed too in an early scene when she drives, like a NASCAR expert, Edward’s sports car, then again in the bathtub scene, where she sexually enfolds him in her extra-long legs. But, after their goodbyes, when Edward unexpectedly returns (in a white stretch limo) to Vivian’s apartment at the very end of the film, he scales the fire escape (in spite of his fear of heights) to “rescue the princess in the tower.” He has undergone a total conversion, from emotionless corporate raider to brave, forgiving and loving human.

Tellingly, he asks the now red-haired (and post-feminist) Vivian what happens after the knight rescues the princess, she replies that she saves the hero “right back,” another revelation of a “reversal of gender roles” (Scala 38).18 And, as Genz recently put the question of the “post-feminist woman” (PFW). The PFW wants to “have it all” as she refuses to dichotomize and choose between her public and private, feminist, and feminine identities. She rearticulates and blurs the binary distinctions between feminism and femininity, between professionalism and domesticity, refuting monolithic and homogeneous definitions of postfeminist subjectivity.19

Reddy, in his analysis of this film posits it as a mirror of the sexual revolution of the 1960s and 1970s (380-381), whereby prostitution is permissible and sexual desire is destygmatized, but still stands in opposition to love, since both characters, now mutually devoted to each other, give up their life of “mere appetites.”20 Edward is thus a better man, Vivian a better woman.

Casablanca

Going back now to the World War II era, we will glance briefly at the great 1942 classic, Casablanca, in which, again surprisingly and ironically, the bitter and cynical refugee hero Rick Blaine (Humphrey Bogart) is transformed not by passionate love, but in this case through a self-effacing compassion. He just wants his beloved Ilsa (the woman between two men story), played famously by Ingrid Bergman) to be happy, for, as he remarks to her—“We’ll always have Paris.”

In the final sequence, Rick, his tough-guy veneer now gone, surrenders two objects, one tangible, the other human—i.e., the vital letters of transit for transport out of Morocco, along with his chance for love with Ilsa. In a meeting with her and her husband Lazlo (the Resistance-fighter) at the Casablanca airport, the now-noble Rick swallows his resentment toward her and yields himself to a new emotion, empathy mixed with admiration for both Ilsa’s devotion and Lazlo’s political cause. And he opines: “It doesn’t take much to see that the problems of three little people don’t amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world.” In a dramatic gesture of magnanimity, Rick turns Ilsa over to the freedom fighter. Generosity and self-sacrifice redeem the hero as it will the other protagonists, even in different ways.

Beauty and the Beast

At this point, we will turn to three animated films (one of which is inspired by a live-action archetypal film produced just a few years after Casablanca). I refer to Beauty and the Beast, known today mainly through the 1991 Disney version. The lesser-known account that inspired the modern and magical remake is the Jean Cocteau classic, a contemporary parable based on a seventeenth-century French tale.

The flawless Belle—to pay for her father’s transgression and obliged to dwell within the Beast’s castle—finds the beast repulsive, but, eventually, love is the potion that will transform both her and the Beast within; he is saved through Belle’s own generous change of heart as she responds to his kindness and favors. Similarly, Belle’s pity, patience, growing admiration and slowly-receding fear of the Beast, brings her to lower her guard and embrace the creature.

Once she does love him (as foretold), the enchantment magically evaporates, the Beast is tamed and everything is joyfully transformed—by their love and new-found respect for each other.21

Hercules

Redemption of a different sort rescues the mythological hero Hercules from the depths of weakened loss and despair. In this 1997 Disney film, the once-powerful and immortal youth attempts to save the life of Megara, his beloved (to provoke the hero, she was slain by Hercules’ nemesis Hades). His awesome powers had been taken from him by the villain but Hercules miraculously regains his strength through mutual love, and is on his way to become a “true hero”— just as (Samson-like) he lifts a huge column that had fallen on Meg. He is wholly and joyfully restored—by love—as a proper and divine hero, and elevated to Mt. Olympus.

Tangled

In Disney’s 2010 Tangled, the heroine Rapunzel undergoes a major personality shift as a result of her encounter with the hero Eugene. It is in fact he who is responsible for getting her out of the imprisoning tower (using a ruse along with the appeal of the mysterious tiara—it’s hers, it is discovered, and she’s the princess!).

In an interesting twist and role-reversal, Eugene tells Rapunzel that she was his new dream and Rapunzel says he was hers. Eugene dies in Rapunzel’s arms. In despair, Rapunzel sings the “Healing Incantation,” and begins to cry. Moved by her love and kindness, the last remnants of a magical flower’s enchantments condense in her tear, which heals Eugene. Later, the two return to the castle to meet her parents and eventually marry, living happily ever after. Rapunzel is redeemed through reciprocal love.

Excalibur

One must expect courtly themes in a medieval film like Excalibur (1981), set presumably in the late fourteenth or fifteenth century, bearing “mythical truth, not historical,” according to its director John Boorman.22 When the charismatic character of Lancelot first appears, he battles with Arthur’s knights, then with Arthur himself. Summoning such superhuman power that the sword Excalibur is cracked in half, Arthur overcomes Lancelot, though the new champion enigmatically but with great nobility bows to the king and offers him fealty.

With the twelve-year peace across Britain established, along with the Round Table and its famed fellowship, Arthur proclaims he will marry. The relationship between Lancelot and Guinevere at first encapsulates what Scaglione named (see above) the “impossibility of communicating with the love object (topos of ineffability).” But then, while escorting the bride Guinevere to the wedding (each, now love struck, having already undergone a coup de foudre), Lancelot is asked by her if he will find a soul mate to love and marry. His reply goes like this: I have found someone. It is you, Guinevere. I will love no other while you live. “I will love you always as queen and wife of my best friend.”

Several scenes later, the queen is charged with adultery and Lancelot (now aware of her unhappy marriage) is at once named her champion—to defend her honor. Such a scenario is familiar to scholars, but surely the millions of non-specialists who have seen the film must relate somehow to this courtly episode.

As if enacting a Occitan love lyric, each has been mightily unfaithful: Guinevere in her longing glances, Lancelot in his fixed staring. But finally they must surrender to their passion. Their shameful infidelity, a deep wound, paralleled by Arthur’s own (unwilling) incestuous coupling with his half-sister Morgana, brings on a terre gaste, a horrid, morbid and gross wasting of both Arthur’s body and the land. The courtly and anti-courtly elements here predominate: the lovers’ religion of love easily nullifies any idea of a stylized game of flirtation. No one is improved this time.

Roxanne

In the romantic comedy, Roxanne (1987), brilliantly adapted by Steve Martin from Rostand’s Cyrano de Bergerac, the astronomer heroine (Daryl Hannah) argues with the genuinely courtly hero (C. D. Bates, Martin’s tennis-playing fireman). In the final sequence (to this woman between two men story) the hero reveals himself as the epitome of generosity by interceding for another man and wooing the heroine on his behalf. Bates says in the end that all Roxanne wanted was the perfect man who was both physically beautiful, emotionally mature and verbally adept.

Finally, Bates (who loved her from the beginning, but direct communication with her was not possible—once more, the ineffable!) and Roxanne forgive one another as she confesses her love for him, in spite of his extraordinarily characteristic nose: it gives him uniqueness, she thinks, observing that flat-nosed people are boring and featureless. Feelings of compassion, admiration, tenderness and understanding change her point of view. The joyful humor and big-heartedness of the film charm the viewer.

The Matrix

We turn next to a blockbuster, the mysterious 1999 science fiction “cyberpunk-cyber thriller,” The Matrix. Amidst all the computer-generated graphics, amazing action scenes and visual effects, futuristic costumes, the enigmatic significance of The Matrix itself, and the secretive feelings Trinity (Carrie Ann Moss) experiences for the hero, Neo (Keanu Reeves), the story really embodies a simple and beautiful fairy-tale component. Trinity’s destiny was to fall in love with “the One” (prophesied as a savior-healer and super manipulator of The Matrix).

The romantic relationship of the two is not revealed until the very end of the film, but Trinity’s act of kissing Neo powerfully resuscitates him within the sentient world (his interfaced physical body) and within The Matrix as well, where his avatar has been active. It is a phenomenal moment when the obscure meaning of The Matrix, Trinity’s love (from afar!) for Neo and Neo’s resurrection and fate are revealed all at once. Trinity does not have to quest for Neo: his sentient body remained right there with her in the laboratory. One can argue that Neo’s life is saved (literally) through the efforts and love of a beloved: Trinity has loved Neo all along. One can also posit that Neo’s acceptance of his destiny as “the One” is augmented by his awareness of Trinity’s love for him.

At the very opening of the film’s sequel, The Matrix Reloaded, the two have now become lovers, and, in one of the film’s final sequences, Neo has a choice: save mankind from extinction (it would happen through a “system reboot”), resulting in the survival of the destructive machines (but not humanity), or choosing to save Trinity’s life: in a face-to-face battle with an Agent (humanoid robot of The Matrix), she crashes out of a window and a bullet pierces her heart. In his abbreviated and breathtaking quest, Neo catches her in mid-air, but she dies. Loath to allow Trinity’s death, Neo uses his superhuman abilities to remove the bullet and revive her. The balance of the two scenes is perfect: in The Matrix it is Trinity who rescues Neo, while in the sequel Neo the hero saves his beloved through love. These films do not illustrate every aspect of courtliness or court culture, but the revealing moment does transport the viewer to a realm of heightened emotion. As in Hercules, love reigns supreme.23

Slumdog Millionaire

Our final film is Slumdog Millionaire, billed as a kind of bildungsroman, a straightforward story about Jamal Malik, an eighteen-year old orphan from the slums of Mumbai. But the film has multiple strata, and underlying the story is Jamal’s search for his “far-away love”—a theme made legendary by twelfth-century Occitan poet Jaufre Rudel’s amor de lonh.24 As the film’s narrative revolves around “Kaun Banega Crorepati,” the Indian TV version of Who Wants To Be A Millionaire? each chapter of Jamal’s increasingly layered story reveals where he learned the responses to the show’s seemingly impossible questions.

To witness the unfolding of Jamal’s life journey—surviving as a street urchin/career thief, his many colorful adventures, gang encounters, his job serving tea in a call center—helps to explain several mysteries, like how and why he ended up as a featured contestant, but most especially how he knows the answers. His life story—in reality a quest—includes being orphaned at an early age; growing up with an older brother, who was both his guardian/protector and antagonist (a kind of rival and dark “other”); and having a relationship since childhood with another orphaned child, a girl named Latika.

A parallel plot line deals with the law—in the present-time episodes, the police grill him to determine how Jamal can be doing so well on the show when others who are brighter, more educated and wealthier fail. Is he cheating? Is it purely luck? But the fact is, the complex and interwoven story is simply a tale of love: every action of Jamal is motivated by his search for his lost childhood love, Latika.

The resplendent joy manifested in the final sequences—an emblem, we recall, of courtly life (Battais 135)—unlocks all the puzzles and enigmas of the film.25 With great generosity of character, Jamal, enduring and shaking off all sorts of suffering and pain, was searching endlessly for Latika: that is why he found a way to get himself recruited to be a contestant for the game show, for he knew she would be watching and that they would be able to meet together, finally, at a designated locale, and no doubt live “happily ever after” and in joy.26

Conclusion

As we have seen, in these selected films (and in many other contemporary ones) transformation through kindness and love frequently manifests itself as a part of the finale. The quest motif very often subsumes the conversion—not necessarily as dramatic as an Augustinian one—yet nevertheless resulting in the rescue of the hero/heroine, where rescue is a generic term including redemption, resuscitation and/or vindication. Melvin Udall, Edward and Vivian, Lancelot, Neo and even Rick Blaine—all are made over or made better by love. Beauty and the Beast, Hercules, Rapunzel and Eugene—these are characters transformed from within; Jamal Malik’s life quest, motivated by a far-away love, ends in a glorious epiphany. An explanatory rationale for the preceeding essay might suggest how faintly aware of these themes our readers might be, but the need remains to inform them of their exact correspondence with courtly love themes. However much it has been transplanted, the courtly legacy sustains. And “the better man” (or woman) survives today.

1 William A. Reddy, The Making of Romantic Love, 14-16; on “desire as sexual appetite,” see 105-107, 220, 351-352; on romantic love and anthropology, 16-21. See as well James Schultz, Courtly Love, the Love of Courtliness…, xvi, xxi, 91-94 (on the courtly paragon)—another recent publication, more specifically on courtly love itself, that posits an eroticization of noble power arising from paradigmatic roles of refinement and social distinction.

Also topically of interest is Galician’s work, Sex, Love and Romance, more negatively-oriented self-help guide than scholarly analysis, deals with “rescue fantasies” (26), courtly love, 28-29, as well as more than a few films, including Coming to America (156), Ever After and Far and Away (169), Legally Blonde (199), Jerry Maguire (206) and What Women Want (138). ?

2 Reddy’s focus unfortunately occludes the influences on twelfth-century European verse and romance of, among others, antecedent Arabic poetry as well as Marian devotional lyrics. ?

3 Magda Bogin, The Women Troubadours, p. 56. ?

4 Celestino Deleyto, “Between Friends,” 169. ?

5 Selection was nowhere near as systematic as that found in the modern media study by Johnson and Holmes; their “RomCom” films all had implications for adolescents, containing in fact (they concluded) contradictory messages (366) with both desirable and undesirable outcomes to romantic relationships; only four of the forty films studied seemed familiar to me (You’ve Got Mail, Runaway Bride, What Women Want, and Sabrina—all still non-courtly it would seem). ?

6 This essay is dedicated to a colleague and friend of over forty years, Deborah Nelson-Campbell of Rice University.

Regarding other films I might have selected for study here, or recent scholarship that I might have “engaged” with, lack of space obliges me to disregard a spate of references to medieval legacies in cinema: medieval scholar Kathryn Hume deals mainly with fantasy, not courtly matters; extreme and heavily theoretical works like Bernau and Bildhauer’s Filming the Middle Ages or Pugh and Aronstein’s The Disney Middle Ages (major recipe discovery: traditional gender roles are reinforced in Disney movies, and Tangled is labeled “racist, speciesist…”—204 ). In theme-based studies like A Knight at the Movies, Aberth is oriented more to epic than romance and to films like Camelot, El Cid, Robin Hood, Seventh Seal, The Navigator, or to Joan of Arc films, and he does not mention any potential aspects of courtly values; while comprehensive and definitive Finke and Shichtman’s Cinematic Illuminations focuses on historicism and film conventions and does not deal with courtly subjects, nor does Elliott’s more recent Remaking the Middle Ages whileoffering innovative semiotic and historiographical analyses. Driver and Ray’s The Medieval Hero glosses over chivalry and knighthood (12-13, 44-45, esp. 73-87) but does not confront courtly issues directly. Laurence Raw reviews several other recent books in this category. ?

7 See C. Stephen Jaeger, Ennobling Love: In Search of a Lost Sensibility. For D. W. Robertson, the medieval phenomenon never existed: “I have never been convinced that there was any such thing as what is usually called courtly love during the Middle Ages” (1). ?

8 On fin’amors see Reddy, 164-167; also, Burns, Kelly and Monson provide full details and background on the subject; see Kim for the term “amour courtois.” ?

9 On this work, Burns writes with urgency (47): “As courtly heroines resist, recast, and manipulate paradigms of femininity, the standard scenarios available for male lovers shift as well. The anomalous and highly courtly fairy heroine in Marie de France’s twelfth-century Lai de Lanval, for example, openly displays the stunning beauty and refined behavior of the classic, commodified courtly lady while riding heroically to defend her seemingly helpless lover in a legal suit. The effect of this woman’s uncharacteristic participation in the legal system at King Arthur’s court is to disrupt it substantially and to defy simultaneously our preconceived notions of gendered options in the courtly world […]. While this heroine plays both parts of lovely lady and heroic knight, her lover Lanval is cast as stunningly ‘beautiful’ but not effeminate. He is a courtly suitor propositioned atypically by the lady’s expression of desire and a lover not required to prove his chivalric mettle in deeds of prowess”—obviously a view of the text quite different from mine. ?

10 My methodology will not include reference to courtliness or to the pragmatics of politeness/impoliteness (see e.g., Grice, Studies in the Way of Words); nor will I deal with obsessive-compulsive, erotic and neurotic Tristan & Iseut-type passionate love, as demonstrated in the movie 10 (George fanatically pursues Jenny) and/or Fatal Attraction (psychopathic Alex hounds Dan endlessly). As Genz observes (119), “[t]he film’s villain, Alex Forrest (Glenn Close), is forcefully prevented from ‘having it all’ as her joint desires to succeed in her career and have a child with her lover are represented as equivalent to madness and ultimately resulting in death. Thus, the backlash reinforces the division between professional and domestic world […], maintaining that women have to opt between a typical existence as a woman and independence.” On the other hand, At First Sight features a generous female (another “gender-bending” role reversal) who attempts to “save” the blind hero (i.e., find a way to bring him sightedness) but complications thwart her success. ?

11 Contemporary relevance is found as well in the writings of theorist Slavoj Zizek who saw courtly love as masochistic; one reviewer wrote that Zizek “sees courtly love everywhere still. It’s not a medieval phenomenon only, but a contemporary one. The femme fatale is an heiress of the cruel lady of courtly love […].” (Leithart, “Zizek and Courtly Love”—a account of The Metastases of Enjoyment: On Women and Causalityby Zizek.) ?

12 Battais, 133-135. Cf. G. Duby, ”Le modèle courtois,” in Histoire des femmes en Occident, 261-276. Reddy, 108-109, 219-220, describes what he calls a “longing for association” in the context of romantic love. ?

13 De amore, ed. Walsh, 1.6.371 (146), 377 (148), 399 (156); 2.8.44 (282). ?

14 See C. S. Lewis, Allegory of Love. On “love service” to/for the Lady, see Grossel’s essay. ?

15 Surprisingly, the final scene of Saturday Night Fever in which Tony and Stephanie conclude the story, reveals a similar sentiment: Stephanie—“There were other reasons why I was hanging around you. / Tony—What do you mean? / St—You made me feel better. You gave me admiration, you know? Respect. Support. / T—Stephanie, maybe now, when I’m going to be in town, maybe we could see each other. I don’t mean like that. I know you’re thinking I’m promoting your pussy. I mean like friends. Like you said: we could help each other. / St—You want to be friends? / T—I’d like to be friends with you. / St—Do you think you know how? Do you think you could be friends with a girl? Could you stand that? / T—The truth? I don’t know. I could try. That’s all I can say. / St—OK.” < http://www.script-o-rama.com/movie_scripts/s/saturday-night-fever-script-transcript.html>. Accessed 12 Oct. 2015. ?

16 For Deleyto (170), this film curiously reveals a “postmodern aesthetic of ironic vampirization of traditional rituals.” ?

17 See Peberdy’s article. For Pretty Woman, Reddy, 176-179, 180, sees parallels with the Lancelot romance by Chrétien de Troyes ; for Lancelot and adultery, parallels with Casablanca. ?

18 Perhaps a stretch, but I see a parallel here with the famous pastorela of innovative Occitan troubadour Marcabru: the rhythm and tone of the dialogue, its frankness (the shepherdess, in the chilly wind, has admirable nipples; the knight wants to see her beneath him to do together the “sweet thing” (per far la cauza dousanna), etc.) remind me of the banter between Edward and Vivian, particularly during the first half of the film. ?

19 Genz, 98. The term today is the “higher-harder-faster school of female achievement” and, in the oracular proclamation of Ms. Sandberg (CEO of Facebook): “require your partner to do half the work at home, don’t underestimate your own abilities, and don’t cut back on ambition out of fear that you won’t be able to balance work and children.” (Kantor NYT) ?

20 In this regard, see Jeffers-McDonald on the sub-genre “radical romantic comedy” of the sixties (59-84), that interrogates romance’s ideology itself, a result of the profound social changes of the era; she perceives in such films a conspicuous self-reflexivity, self-consciousness and self-absorption—what one called narcissism back in the day. ?

21 Fairy-tale specialist Jack Zipes has this to say about the numerous Beauty and the Beast films: they are “self help films [that] basically [offer] variations on the same theme: how to help attractive, seemingly strong women realize that appearances are deceiving and that happiness in wedlock is within their grasp if they understand the goodness of good-hearted men” (239). ?

22 As for relevance and continuity of appeal, one may note the film’s total domestic gross: $35 million—a testament to its success with audiences. ?

23 Chaos, death and mayhem reign in yet another film worthy of mention in this context: The Wild One (1953): the motorcycle hooliganism cannot overshadow the eight-minute romantic and quiet interlude (the hero safely escorts the girl away from violence), during which a desperate Kathy (Mary Murphy) expresses to the brooding Johnny (Marlon Brando) her yearning for salvation by “someone” who will rescue her from small-town mediocrity. ?

24 See, for example, Jaufre Rudel, “Quan lo rius de la fontana…” (amors de terra lonhdana) and “Lanquan li jorn son lonc en may…” (l’amor de lonh) in Poètes et romanciers du Moyen Age, ed. Pauphilet, 780-784. ?

25 Channeling St. Francis of Assisi, Battais observes (136) that pain delights the courtly lover since it can no doubt lead to ultimate happiness. ?

26 Michael Novak observes, on the very subject of that “rarefied spiritual passion” in a “higher sphere” known only to romantic lovers:. “Romantic love is a transfiguring force, something beyond delight and pain, an ardent beatitude, purer, more spiritual, more uplifting than physical “hooking up.” It is not a sated appetite, but in fact quite the opposite. It loves the feeling of never being satisfied, of being always caught up in the longing, of dwelling in the sweetness of desire […]. This is why romantic love desperately needs obstacles […].” On this, Zizek would say that such impediments elevate the value of the beloved (see note 10). ?

*First published in 2015 in the Americana Journal. Creative Commons.

By Douglas Galbi

Good lady, you may burn or hang him

or do anything you happen to desire,

for there’s nothing that he can refuse you,

as such you have him without any limits.{ Bona domna, ardre.l podetz o pendre,

o far tot so que.us vengua a talen,

que res non es qu’el vos puesca defendre,

aysi l’avetz ses tot retenemen. } [1]

Men have long been sexually disadvantaged. While men’s structural disadvantages are scarcely acknowledged within gynocentric society, a small number of medieval women writers courageously advocated for men. In Occitania early in the thirteenth century, the extraordinary trobairitz Lady Castelloza spoke out boldly against gender inequality in love and men having the status of serfs in sexual feudalism.

And if she tells you a high mountain is a plain,

agree with her,

and be content with both the good and ill she sends;

that way you’ll be loved.{ e s’ela.us ditz d’aut puoig que sia landa,

vos l’an crezatz,

e plassa vos lo bes e.l mals q’il manda,

c’aissi seretz amatz. } [2]

Just as is the case for many women today, many medieval women didn’t adequately support and defend men. When Giraut de Bornelh asked his lovely friend Alamanda about his love difficulties, she advised him to be totally subservient to his lady. Alamanda was a maiden to that lady. Lord Giraut apparently had lost his lady’s love by seeking sex with a woman who was not her equal, probably none other than her maiden Alamanda. But what had that lady done to him? She had lied to him at least five times before! When women speak, men should not just listen and believe. Unwillingness to question a woman led a Harvard Law professor to personal disaster. Men should not act as doormats for women or as women’s kitchen servants.

The trobairitz Maria de Ventadorn insisted to Gui d’Ussel that a woman should retain her superior position even in a love relationship with a man. Gui felt that men and women in love should be equals. But Maria wanted men to fulfill all the pleas and commands of their lady-lovers. That’s the pernicious doctrine of yes-dearism. Just say no to female supremacists!

Lady {Maria de Ventadorn}, among us they say

that when a lady wants to love,

she should honor her love on equal terms

because they are equally in love.

…

Gui d’Ussel, at the beginning lovers

say no such thing;

instead, each one, when he wants to court,

says, with hands joined and on his knees:

“Lady, permit me to serve you honestly

as your servant man” and that’s the way she takes him.

I rightly consider him a traitor if, having given

himself as a servant, he makes himself an equal.{ Dompna, sai dizon de mest nos

Que, pois que dompna vol amar,

Engalmen deu son drut onrar,

Pois engalmen son amoros!

…

Gui d’Uissel, ges d’aitals razos

Non son li drut al comenssar,

Anz ditz chascus, qan vol prejar,

Mans jointas e de genolos:

Dompna, voillatz qe-us serva franchamen

Cum lo vostr’om! et ella enaissi-l pren!

Eu vo-l jutge per dreich a trahitor

Si-s rend pariers e-s det per servidor. } [3]

Because of their great love for women, men are reluctant to demand that women treat them with equal human respect and dignity. Men tend toward gyno-idolatry. The man on his knees before a woman, with his hands clasped, is making a gesture of faithful subordination. She then puts her hands around his hands to complete this feudal gesture known as the immixtio mannum {intermingling of hands}. A man today who goes down on his knee to ask a woman for her hand in marriage is preparing to be a vassal to his woman-lord midons. That’s folly. That’s fine preparation for a sexless marriage. From studying Ovid the great teacher of love to modern empirical work on sexual selection, men should know that self-abasement is a losing love strategy.

Oh Love, what shall I do?

Shall we two live in strife?

The griefs that must ensue

would surely end my life.

Unless my Lady might

receive me in that place

she lies in, to embrace

and press against me tight

her body, smooth and white.

…

Good Lady, thank you for

your love so true and fine;

I swear I love you more

than all past loves of mine.

I bow and join my hands

yielding myself to you;

the one thing you might do

is give me one sweet glance

if sometime you’ve the chance.{ Amors, e que.m farai?

Si garrai ja ab te?

Ara cuit qu’e.n morrai

Del dezirer que.m ve,

Si.lh bela lai on jai

No m’aizis pres de se,

Qu’eu la manei e bai

Et estrenha vas me

So cors blanc, gras e le.

…

Bona domna, merce

Del vostre fin aman!

Qu’e.us pliu per bona fe

C’anc re non amei tan.

Mas jonchas, ab col cle,

Vos m’autrei e.m coman;

E si locs s’esdeve,

Vos me fatz bel semblan,

Que molt n’ai gran talan! } [4]

The medieval trobairitz Castelloza sympathized with men’s subordination in love. She loved a man who didn’t love her. A woman today in such a situation might open a dating app and enjoy a huge number of solicitations from men. Then, if necessary to boost her self-esteem, she might go for sexual flings with a few, or at least exploit traditional anti-men gender dating roles to get some free dinners. With a keen sense for social justice, Castelloza refused to live according to such female privilege:

I certainly know that it pleases me,

even though people say it’s not right

for a lady to plead her own cause with a knight,

and make long speeches all the time to him.

But whoever says this doesn’t know

that I want to implore before dying,

since in imploring I find sweet healing,

so I plead to him who gives me grave trouble.{ Eu sai ben qu’a mi esta gen,

Si ben dison tuig que mout descove

Que dompna prec ja cavalier de se,

Ni que l tenga totz temps tam lonc pressic,

Mas cil c’o diz non sap gez ben chausir.

Qu’ieu vueil preiar ennanz que.m lais morir,

Qu’el preiar ai maing douz revenimen,

Can prec sellui don ai greu pessamen. } [5]

Castelloza recognized that, in pleading with a man for love, she was transgressing the norms of men-oppressing courtly love. When women treat men merely as dogs, women don’t experience the full gift of men’s tonic masculinity. The master dehumanizes herself in dehumanizing her man-slaves. Castelloza, in contrast, understood that a man’s love can ennoble a woman. She understood that a man can offer much to even the most privileged woman.

I’m setting a bad pattern

for other loving women,

since it’s usually men who send

messages of well-chosen words.

Yet I consider myself cured,

friend, when I implore you.

for keeping faith is how I woo.

A noble women would grow richer

if you graced her with the gift

of your embrace or your kiss.{ Mout aurei mes mal usatge

A las autras amairitz,

C’hom sol trametre mesatge,

E motz triaz e chauzitz.

Es ieu tenc me per gerida,

Amics, a la mia fe,

Can vos prec — c’aissi.m conve;

Que plus pros n’es enriquida

S’a de vos calqu’aondansa

De baisar o de coindansa. } [6]

Men’s lack of imagination and unwillingness to protest helps to keep them in their gender prison of gynocentrism. Men rightly appreciate, admire, and love courageous, transgressive women like the trobairitz Castelloza. But men must take responsibility for winning their own liberation. A man showing loving concern about his close friend getting married isn’t enough. Men should be more daring and, like Matheolus, raise stirring voices of men’s sexed protest. Men Going Their Own Way (MGTOWs) struggled against misandry and castration culture even in the Middle Ages, and they continue to do so today. MGTOW is merely prudent personal action. To dismantle gynocentric oppression, men must recover, create, and disseminate protest poetry as potent as the medieval troubadours’ feudal songs of men’s love serfdom.

Peire, if spanning two or three years

the world were run as would please me,

I’ll tell you how with women it would be:

they would never be courted with tears,

rather, they would suffer such love-fears

that they would honor us,

and court us, rather than we, them.{ Peire, si fos dos ans o tres

Lo segles faihz al meu plazer,

De domnas vos dic eu lo ver:

Non foran mais preyadas ges,

Ans sostengran tan greu pena

Qu’elas nos feiran tan d’onor

C’ans nos prejaran que nos lor. } [7]

* * * * *

Notes:

[1] Domna and Donzela, “Bona domna, tan vos ay fin coratge” ll. 17-20, Occitan text and English translation (modified insubstantially) from Bruckner, Shepard & White (1995) pp. 92-3. Here’s some meta-data about this trobairitz song. It’s a debate poem (tenso). The currently best critical edition of trobairitz / troubadour tensos is Harvey, Paterson & Radaelli (2010), but it’s expensive and not widely available. For analysis of the genre of tenso, McQueen (2015).

[2] Alamanda and Giraut de Bornelh, “S’ie.us qier conseill, bella amia Alamanda” ll. 13-16, Occitan text and English translation from Bruckner, Shepard & White (1995) pp. 42-3.

[3] Maria de Ventadorn and Gui d’Ussel, “Gui d’Ussel be.m pesa” ll. 25-8, 33-40, Occitan text and English translation (modified insubstantially) from Bruckner, Shepard & White (1995) pp. 38-41. This poem is also available in translation in Paden & Paden (2007). The immixtio manuum isn’t attested prior to 1100. West (2013) p. 211.

[4] Bernart de Ventadorn, “Pois preyatz me, senhor” ll. stanzas 4 & 6, Occitan text and English translation by W.D. Snodgrass from Kehew (2005) pp. 84-5. The Poemist offers online the full text and English translation.

Men’s abasement in sexual feudalism is pervasive in trobairitz song. Men engage in gyno-idolatry and imagine that they will die without a woman’s love:

I bow down to you, whom I love and adore,

and I am your liegeman and your household servant.

I yield myself up to you, who are the noblest

and the best being that was ever born of a mother.

And since I cannot help but love you,

for mercy’s sake, I beg you, don’t let me die.{ Sopley vas vos, cuy yeu am et azor,

E suy vostres liges e domesgiers.

A vos m’autrey, qar etz la genser res

E la mielhers qu’anc de maire nasques.

E, quar no.m puesc de vos amar suffrir,

Per merce.us prec que no.m layssetz morir. }

Peire Bremont Ricas Novas, “Us covinens gentils cors plazentiers,” 3.3-8, Occitan text and English translation (modified) from Kay (1999) p. 217. Peire Bremont Ricas Novas was active in Province from about 1230 to 1241.

[5] Na {Lady} Castelloza, “Amics, s’ie.us trobes avinen” ll. 17-24 (stanza 3), Occitan text from Paden (1981), English trans. (modified) from Paden & Paden (2007). Bruckner, Shepard & White (1995) provides a slightly different Occitan text and English translation of all of Castelloza’s songs. Butterfly Crossings provides an online Occitan text and English translation of the full song, with commentary. Her commentary puts forward orthodox myth in service of gynocentrism:

by virtue of being a woman she is below him socially, thus rendering her statement simultaneously true and drawing attention to the place of women in society as opposed to the artificial pedestal they sit upon in traditional Troubadour poems. Regardless of her title, class, or wealth, in love, much like in life, the woman is beneath the man and must beg his favor like Castelloza here does.

Yup, so Anne of France was beneath day-laboring men gathering stones in fields.

Much influential recent scholarship on trobairitz has been based on dominant gender delusions. A relevant critique:

Gravdal’s argument here is based on her assumption that, for the men, powerlessness is a pose, a rhetorical strategy; the male speaker adopts an abased position only to use it as a springboard to higher status and sociopolitical clout. That Castelloza’s speaker does this as well is frequently overlooked, because it is assumed that for the women, powerlessness is a reality. This assumption is not supported by the evidence for noblewomen’s sociopolitical situation in Occitania during the time of the trobairitz.

Langdon (2001) p. 40.

[6] Castelloza, “Mout avetz faich lonc estatge” ll. 21-30 (stanza 3), Occitan text from Paden (1981), English trans. (modified) from Paden & Paden (2007). Butterfly Crossings again offers the full song, along with commentary. The commentary shows orthodox academic failure of self-consciousness:

Almost smirkingly Castelloza acknowledges that her behavior sets a terrible example for all other female lovers while synchronously encouraging them to do the same. She is not apologizing as much as drawing attention to the solidarity between women who will now partake in this perhaps liberating behavior and act upon their desires as opposed to remaining within the confined roles of passive love interests.

Women unite in liberating behavior: ask men out and buy men dinner!

In Castelloza’s songs, the man she loves has neither voice nor activity. Siskin & Storme (1989) pp. 119-20. Self-centeredness is a common characteristic of women’s writing, particularly in the last few decades of literary scholarship.

[7] Peire d’Alvrnha (possibly) and Bernart de Ventadorn, “Amics Bernartz de Ventadorn,” stanza 4, Occitan text from Trobar, my English translation benefiting from that of Rosenberg, Switten & Le Vot (1998). James H. Donalson provides an online Occitan text and English translation for the full song.