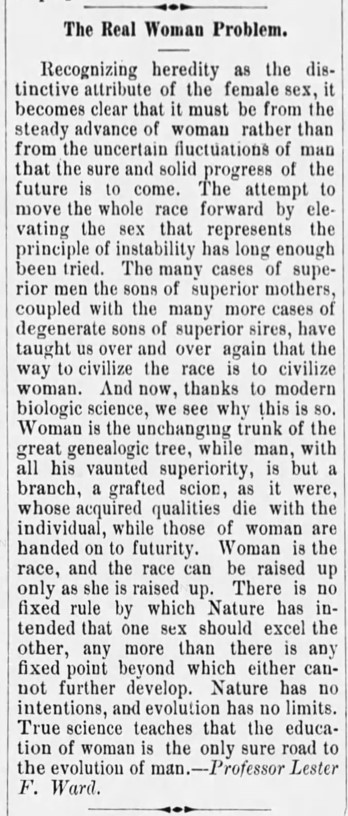

The following piece The Real Woman Problem, by Lester Ward, was quoted in The Montpelier Daily Journal, on November 1, 1888.

Gynocentrism

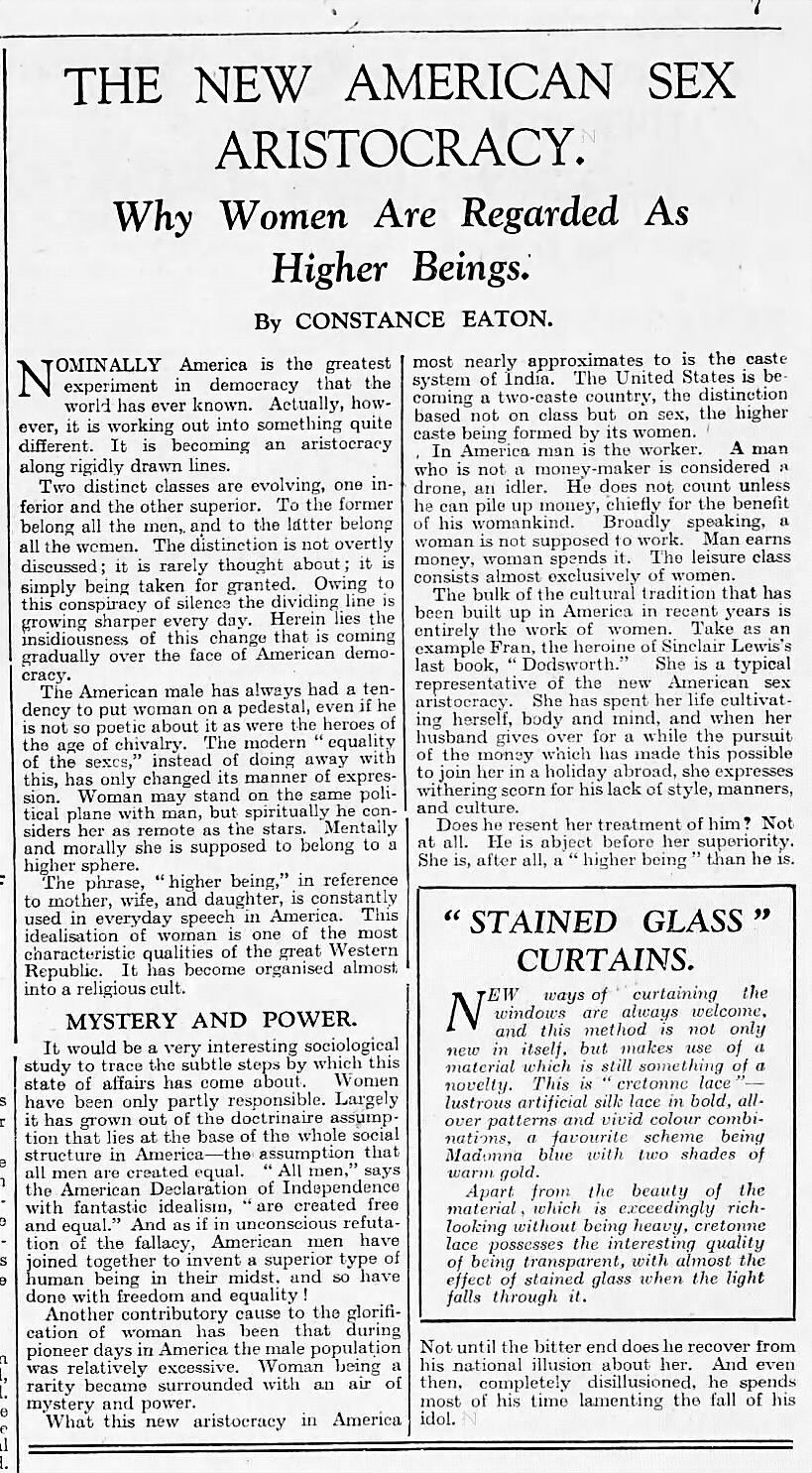

The New American Sex Aristocracy – by Constance Eaton (1929)

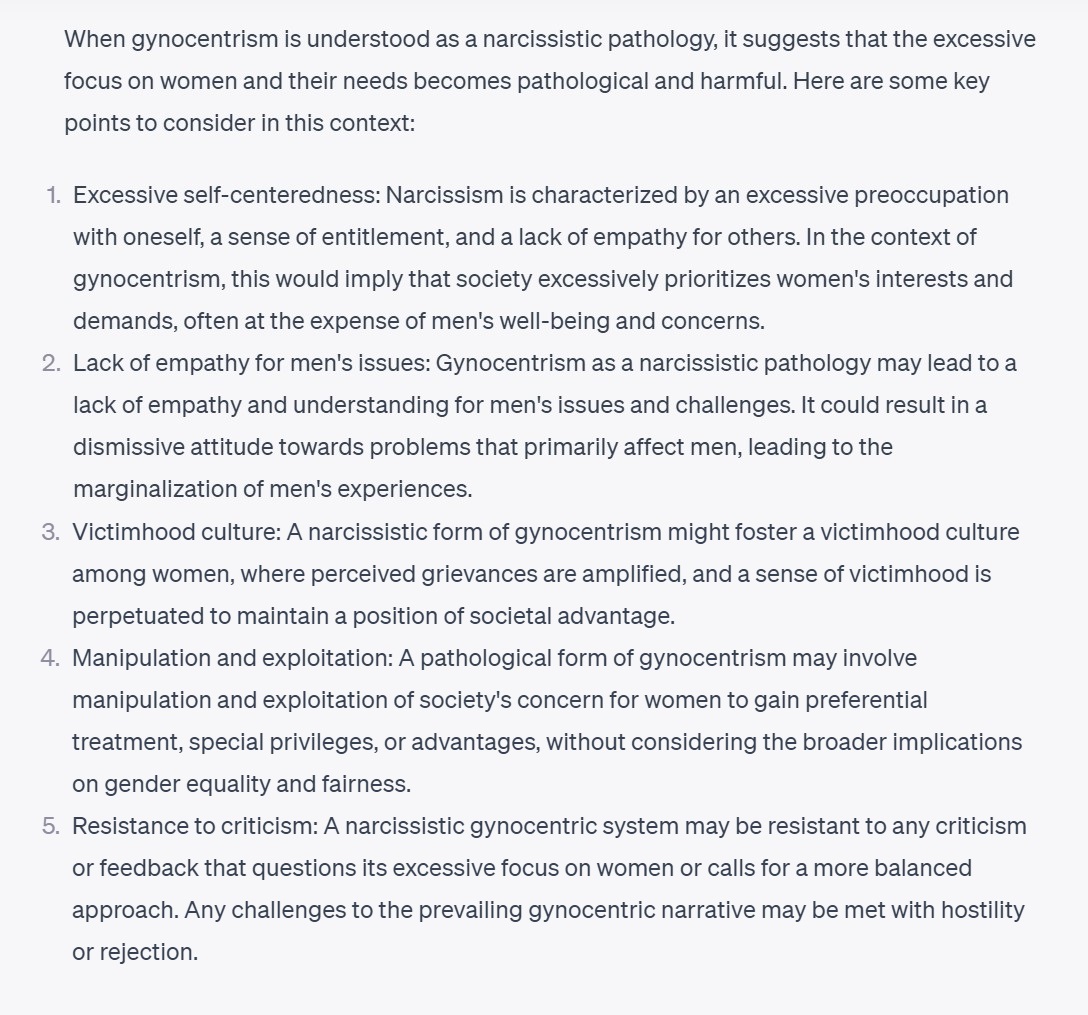

Chat GPT Outlines The Relation Between Gynocentrism & Narcissism

The following are two consecutive answers provided by Chat GPT on the question of a potential relation between gynocentrism and narcissism – PW.

_____________________

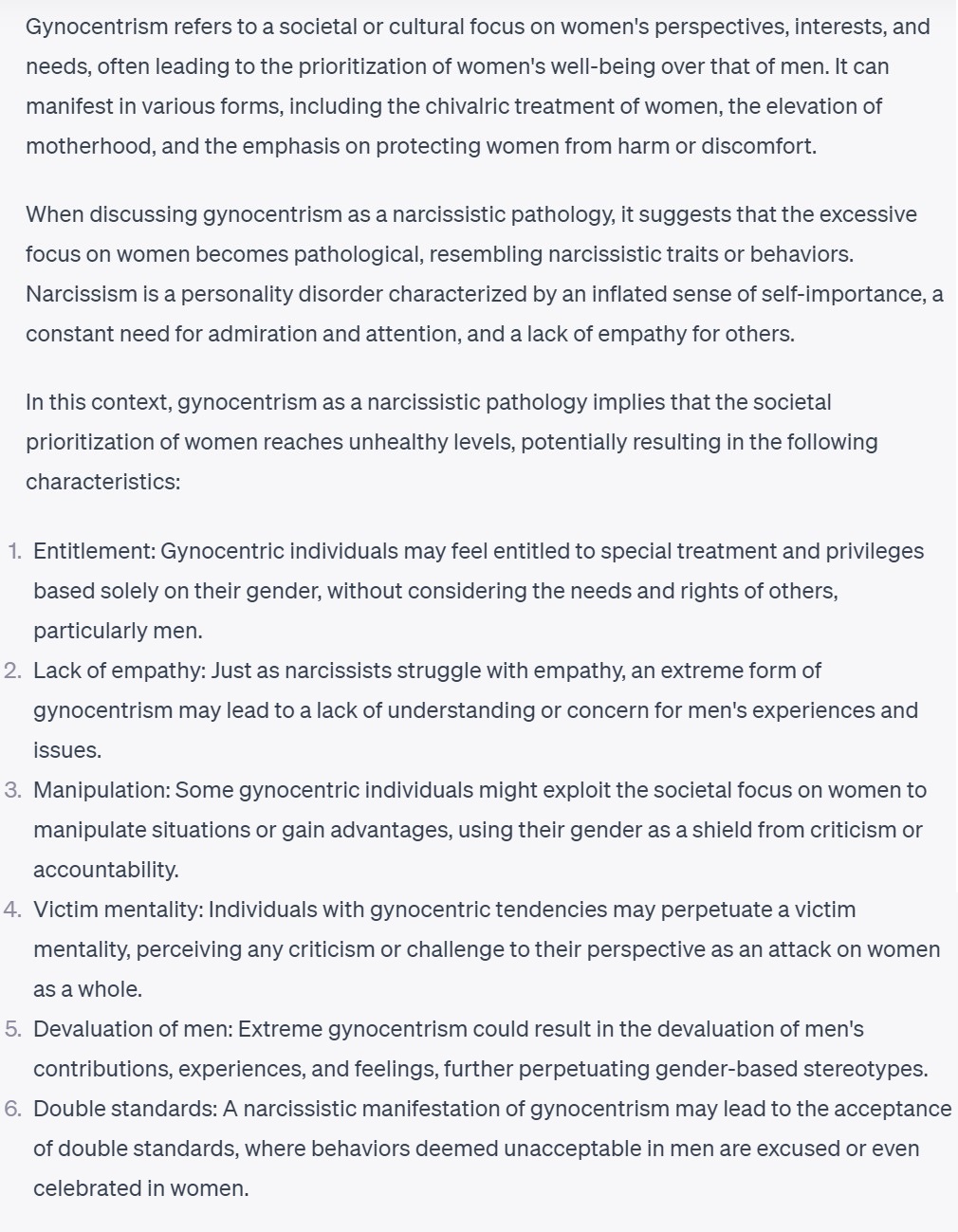

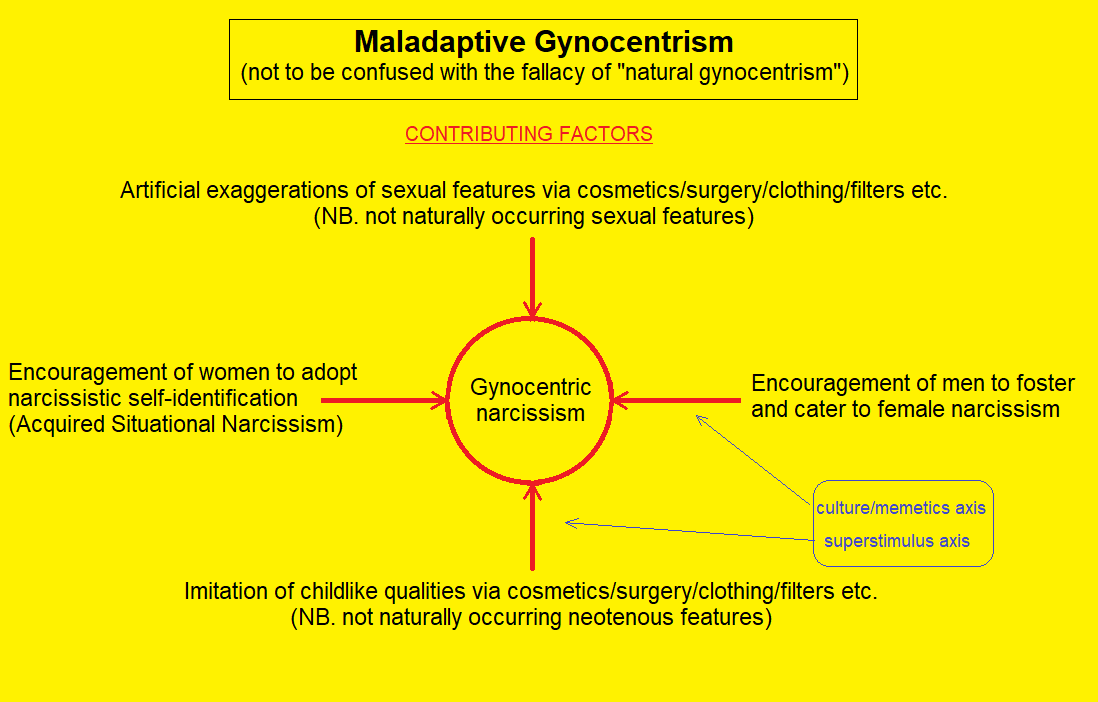

Maladaptive Gynocentrism

The following graphic details the maladaptive form of gynocentrism which often gets misrepresented as a benign theory known as “natural gynocentrism.”

Note: certain behaviors associated with gynocentric narcissism may resemble hypergamy. However such behavior is more accurately classed as a narcissistic self-enhancement instead of survival-based enhancements associated with hypergamy. For more on this distinction see: Narcissism Exaggerates Baseline Hypergamy (2023)

Gynocentrism: A Beloved Feminist Fiction

Lester F. Ward (1841-1913), a scholar of biological and sociological disciplines, was a passionate advocate for first wave feminism and “women’s liberation.” Just like today’s difference feminists he spoke about biological differences between the sexes, and theorized that women were the more superior sex due to evolutionary and reproductive value.

Sound familiar? It should, because it’s the same gynocentrism theory is promoted in the manosphere.

Ward is celebrated as a pioneering male feminist by historian Ann Taylor Allen,1 and Michael Kimmel classifies him as a feminist sociologist.2 And its not only today’s feminists who celebrate his theory: All three waves championed his, or similar gynocentric theories as a triumph of scientific truth and of women’s deserved special treatment.

Protestors may say that feminists have never believed in biology, that they’ve always championed the blank slate theory. Feminists, however, have consistently proven to be opportunists who sometimes deny biology, and then very often appeal to it. For example feminists love to bring attention to biological facts like women’s vulnerability due to smaller size, pregnancy, lactation, menstruation, etc. – not to mention many of the first feminists championed biological gynocentrism (actually using that word) as an appeal for men to pedestalize them.

Lester Ward delivered his famous “Gynæcocentrism Theory” speech to an enthusiastic group of 1st wave feminists in the year 1888 – including Mrs. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Miss Phoebe Couzins, and many others well known.3 The title of the speech was Our Better Halves, and consisted of an elaborate claim that women were biologically superior to males due to their evolutionary and reproductive roles, and thus women were more important than males who were described as mere helpers in the evolutionary scheme.

Ward’s feminist audience rejoiced in his deductions because they seemed to prove the claim of women’s preeminence at a time when the proposal was doubted. According to historian Cynthia Davis, the lending of scientific theory to claims of female superiority “led conservatives to identify Darwin as modern feminism’s ‘originator,’ and Ward as its ‘prophet.”4

First wave feminist Charlotte Perkins-Gilman (1860 – 1935) claimed that Ward’s theory of gynocentrism was the most important contribution to ‘the woman question’ ever made.4,5 Commenting on Ward’s theory to doubters, Gilman wrote “You’ll have to swallow it. The female is the race type; the male is her assistant. It is established beyond peradventure.”6 While continuing to laud Ward’s gynocentrism theory as a brilliant contribution, she expanded on it by suggesting that women were more evolutionarily advanced than men, and that women were continuing to advance at a faster rate than men.4

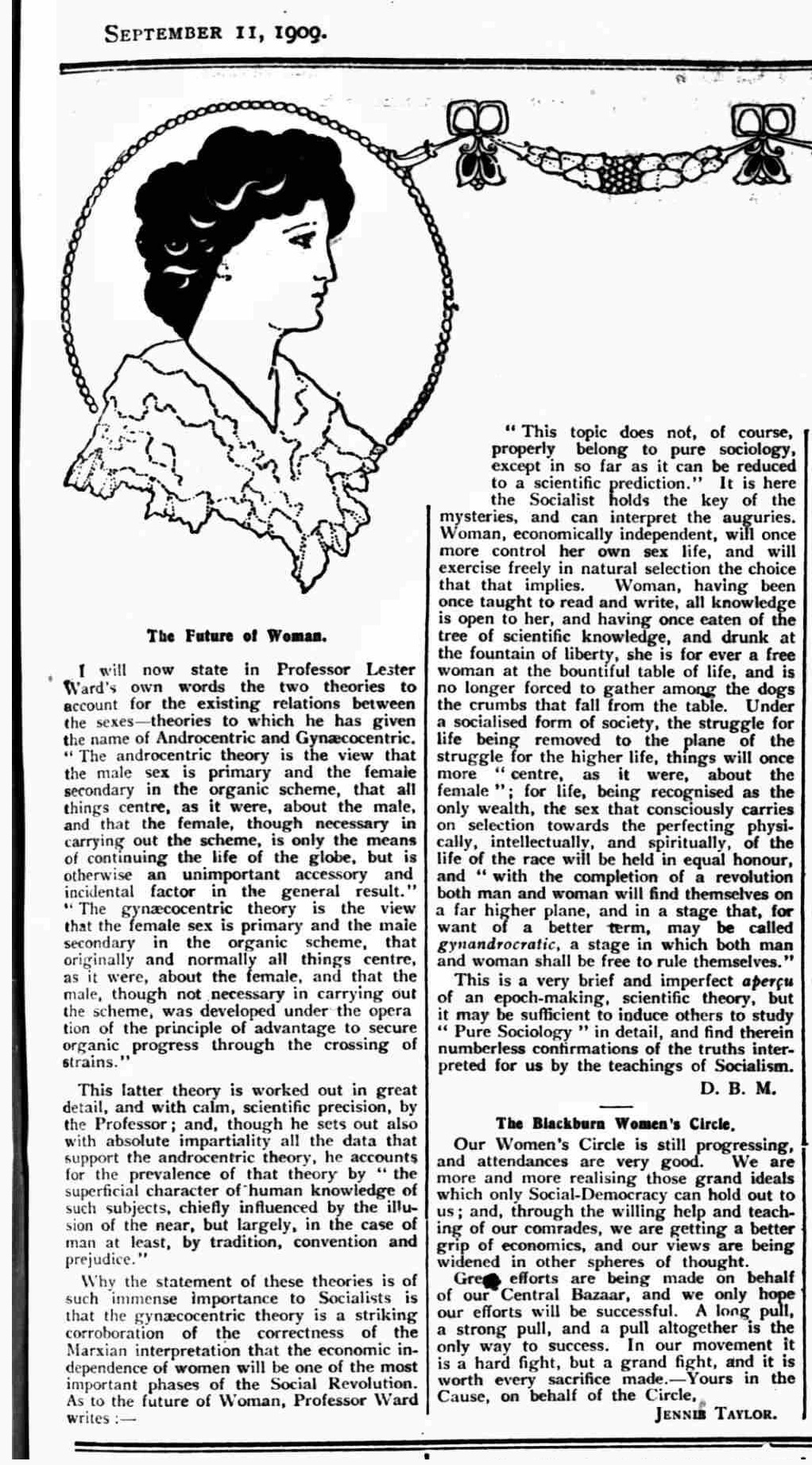

In his 1903 book Pure Sociology,7 Ward published a more lengthy chapter explaining his gynæcocentric theory. His theory travelled around the world and fomented feverish debates, as can be seen from this sample of articles published at the time:

- – ‘Gynæcocentricity’ Poem from the London Punch (1903)

- – The Evolution of Sex According to Lester F. Ward (1909)

- – The Future of Women – by D. M. N. (1909)

- – Ernest B. Bax Responds to Lester Ward’s ‘Gynocentric Theory’ (1909)

- – “The Evolution of Sex” – A Protest Against Ward’s Gynæcocentric Theory (1909)

- – The Book of Women’s Power – edited by Ida M. Tarbell (1911)

- – Woman and Gynæcocentric Social Progress – by S. Nearing (1912)

- – Ernest B. Bax: Examines Lester Ward’s ‘Gynœcocentric Theory’ Fallacy (1913)

- – Some Biological Aspects of Feminism – by R.E. Ryan (1914)

- – The Influence of Gynaecocentric Theory On Feminism – by C. Walsh (1917)

- – Race Motherhood: Is Woman The Original Human Race? – D. Montefiore (1920)

- – Book Review of D. Montefiore’s ‘Race Motherhood’ by D. M. N (1920)

- – ‘Gynocentric Theory’ in Colleges and Popular Culture, by M. M. Knight (1920)

- – The Foundations Of Feminism – by Avrom Barnett (1921)

- – The Lure of Superiority: ‘Gynæcocentric Feminism’ by W.F. Vaughan (1928)

Furthermore, Ward’s gynæcocentrism theory was championed by Marxists as a scientific basis for elevation of women’s rights, as shown in the following article published in Justice, 1909, which reads “Why the statement of these theories is of such immense importance to Socialists is that the gynæcocentric theory is a striking corroboration of the correctness of the Marxian interpretation that the economic independence of women will be one of the most important phases of the Social Revolution.”

After pinning down the origin of this theory, a question arises; Do we really want to keep promoting these feminist-inspired theories today? Whatever the merits of Ward’s biological basis for gynocentrism (well there’s no merit, actually), it has since flourished both in feminist circles and, sometimes, in men’s activist conceptions of the way human evolution works: i.e., we are a hopelessly gynocentric species and we need to get used to it.

Feminists probably like this 135 year old narrative, and they of course have led the way to its institutionalization in the canon of modern ideas. From my observations, those most invested in a gynocentric lifestyle, whether they be men or women, are likely to be the strongest champions of this pseudo-theory today.

For anyone wanting to check the scientific veracity of biological-gynocentrism theories, I can think of no better corpus than that of Peter Ryan; a researcher educated in molecular biology who has debunked all of the usual “scientific” appeals to gynocentrism as amounting to pseudoscience. You can read his article on Ward’s gynocentrism theory here, and his entire series of articles here.

While human relationships and the wider culture can indeed be tilted in a gynocentric direction, this need not be understood as a necessary evolutionary norm. The gynocentrism we witness today can be understood as a maladaptive behaviour resulting from novel cultural forces playing on our biological potentials. Those novel forces act in a similar way to a cellphone in a plane which is why we switch phones to flight mode – nobody wants a corrupted flight program nor any of the novel reactions that would come with it. The plane is definitely not programmed to do spinning cartwheels due to someone’s cellphone interfering, but the existing program has potential to be corrupted to produce that outcome. So likewise, the claim that gynocentrism is hardwired in us as a “natural instinct” may be better understood as a corrupting set of forces playing on our biological mechanisms to generate pathological, maladaptive reactions.

This problem has been succinctly summarized by Hannah Wallen’s concept of the ‘Natural Gynocentrism Fallacy,‘ which refers to the belief that sexually mature women are the most important unit within the human species due to the role they play in reproduction – ie. it is a belief in which women are assumed to be more valuable to human society, and to human relationships, than are men, children and even the perpetuation of one’s genes. A corollary assumption is that women’s lives and wants should be prioritized over those of men and children.

The natural gynocentrism fallacy, according to Wallen, involves a denial of the fact that all adult humans, including women, are child-centric, gene-centric, and utilitarian toward that end. Thus the hypothesis that humans are a ‘gynocentric species’ amounts to a denial of women’s evolutionary value as an instrument of the child’s creation and protection, i.e., not because her gender is valued per se outside this utilitarian function. Wallen summarizes that gynocentrism is not a naturally occurring phenomenon, is not inevitable, and is something that can be corrected. She states that historical gynocentric attitudes that have been treated as “natural,” and thus as the reason why gynocentrism could never be eliminated, are false.

With the knowledge that biological theories of gynocentrism began with first wave feminists, this should at least prompt us to review the assumptions we’ve picked up regarding humans being a gynocentric species. We can at least question the validity of this longstanding feminist dogma, no matter which side of the equation we ultimately fall.

References:

[3] Ward, L. F. Our Better Halves.

[4] Davis, C. (2010). Charlotte Perkins Gilman: A Biography. Stanford University Press.

[5] Gilman, C. P. (1911). The Man-Made World; or. Our Androcentric Culture.

[6] Gilman, C. P. (1911). Moving the Mountain. Charlton Company.

[7] Ward, L. F. (1903). Pure sociology: A treatise on the origin and spontaneous development of society. Macmillan Company.

Gynocentrism As A Narcissistic Pathology – Part 2

The following paper was first published in July 2023 in New Male Studies Journal and is republished with permission.

_____________________________

NEW MALE STUDIES: AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL ~ ISSN 1839-7816 ~ Vol 12, Issue 1, 2023, Pp. 29–44 © 2023

AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE OF MALE HEALTH AND STUDIES

Gynocentrism and female narcissism

The following articles explore the role of narcissism in the context of gynocentric culture & behaviour. This emphasis is not aimed to reduce narcissism to an all-female pathology, but to demonstrate the ways in which female narcissism may lean toward gynocentric modes of expression, much as males demonstrate narcissism in typically gendered ways.

Formal studies in female narcissism by Ava Green (and colleagues) :

-

- Perceptions of female narcissism in intimate partner violence: A thematic analysis (2019)

- Voicing the victims of narcissistic partners: A qualitative analysis of responses to narcissistic injury and self-esteem regulation (2019)

- Unmasking gender differences in narcissism within intimate partner violence (2020)

- Gender differences in the expression of narcissism: Diagnostic assessment, aetiology, and intimate partner violence perpetration (2020)

- Recollections of parenting styles in the development of narcissism: The role of gender (2020)

- Female Narcissism: Assessment, Aetiology, and Behavioural Manifestations (2021)

- Clinician perception of pathological narcissism in females: a vignette-based study (2023)

- Mean Girls in Disguise? Associations Between Vulnerable Narcissism and Perpetration of Bullying Among Women (2024)

- Gendering Narcissism: Different Roots and Different Routes to Intimate Partner Violence (2024)

- Narcissism: it’s less obvious in women than in men – but can be just as dangerous (2024)

- Gender bias in assessing narcissistic personality: Exploring the utility of the ICD-11 dimensional model (2024)

- ‘The Way In Which Narcissistic Women Abuse Is More Likely Overlooked’ – An interview with psychologist Dr Ava Green (2025)

Articles on gynocentrism & narcissism by Peter Wright:

- A. Kostakis & P. Wright – Is gynocentrism a narcissistic pathology? (2011)

- Cornelius Castoriadis: The Narcissistic Social Contract (2014)

- Gynocentrism as a Narcissistic Pathology – Part 1 (2020)

- Gynocentrism as a Narcissistic Pathology – Part 2 (2023)

- Narcissism Exaggerates Baseline Hypergamy (2023)

- Does female narcissism involve any kind of moral responsibility? (2023)

- Vulnerable Narcissism And The Tendency For Interpersonal Victimhood (2023)

- The Two Faces of Feminism: Grandiose and vulnerable (2023)

- Romantic Chivalry Encourages Female Narcissism (2023)

- Gynocentric Economies Eventually Lead To Low Birth Rates (2024)

Articles on the narcissism ~ hypergamy conflation:

- Is It Really Hypergamy—Or Just Narcissism in Disguise? (2025)

- Narcissism vs. Hypergamy: A Comparative Analysis (Chat GPT 2025)

- Evolutionary & Sociological Definitions of Hypergamy: A Synthesized Definition (Chat GPT 2025)

- David Buss’s Hypergamy Theory May Be a Misinterpretation Of Modern Cultural Narcissism (2025)

Research on interrelationship of narcissism and feminism:

- Impact Of Feminism On Narcissism And Tolerance For Disagreement Among Females (2018)

- Evidence for the Dark-Ego-Vehicle Principle: Higher Pathological Narcissism Is Associated With Greater Involvement in Feminist Activism (2022)

- Evidence for the Dark-Ego-Vehicle Principle: Higher Pathological Narcissistic Grandiosity and Virtue Signaling are Related to Greater Involvement in LGBQ and Gender Identity Activism (2022)

Miscellaneous

- Narrative Transference and Female Narcissism: The Social Message of Adam Bede (2003)

- Mental Disorders of the New Millennium: Acquired Situational Narcissism (2006)

- Denis De Rougemont: Romantic Love is “Twin narcissism” (1939)

- Madame Bovary Syndrome (English Translation from the original French paper – 1892

- What Is Madame Bovary Syndrome? (2018)

- I want a man who will “spoil” me (2024)

Informal Articles

- When did getting married become an exercise in acquired situational narcissism? (2007)

- Paul Elam: Narcissism Isn’t Self-Esteem [satire piece]

- Chat GPT Details The Relation Between Gynocentrism & Narcissism (2023)

- Bing AI ‘CoPilot’ On The Relation Between Gynocentrism & Narcissism (2023)

- “Performative femininity” of tradwives may be a manifestation of narcissism (2025)

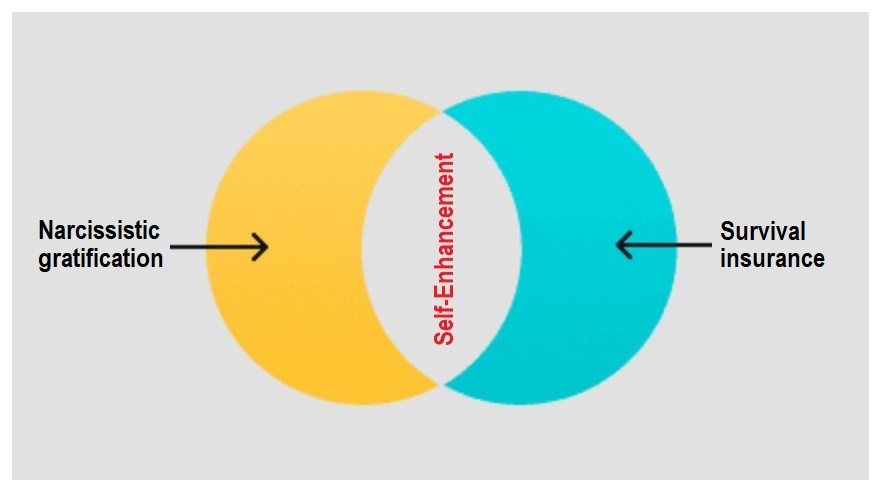

Narcissism Exaggerates Baseline Hypergamy

Many social media commentators discuss the rise of hypergamous behaviors among modern women. Some pose reasonable evolutionary hypotheses for such behavior, but there may be another cause at work – cultural narcissism.

Observations of extreme hypergamy among women may be equally explained by the rise of cultural narcissism in affluent societies (Twenge & Campbell, 2009), a motive that differs from baseline hypergamy, but which nevertheless involves comparable behaviors of self-enhancement and status-seeking.

Society’s encouragement of men in chivalric deference to women, and the associated practice of ‘placing women on a pedestal’, has generated a degree of gendered narcissism among women over time. To frame this differently, Acquired Situational Narcissism can arise with any acquired social status; for example in academic experts, politicians, pop singers, actors – and also in women who, in modern society, are taught that they deserve to be recognised for thier worth, dignity, value, purity, status, reputation and esteem in the context of their relationships with men. This psychological disposition in women, partly a result of traditional chivalry, promotes exaggerated self-enhancement behaviours beyond what evolutionary models of hypergamy would require.

Among narcissistic individuals, studies find higher incidence of hypergamy-like behaviors, indicating that such behavior is not the result of a culture of sexual liberation alone, nor of baseline evolutionary imperatives; it may also be the result of an acquired social class narcissism that says “I deserve.”

Excerpts from narcissism studies:

A third strand of evidence concerns narcissists’ relationship choices. Because humans are a social species, relationship choices are an important feature of situation selection. Narcissists are more likely to choose relationships that elevate their status over relationships that cultivate affiliation. For example, narcissists are keener on gaining new partners than on establishing close relationships with existing ones (Wurst et al., 2017). They often demonstrate an increased preference for high-status friends (Jonason & Schmitt, 2012) and trophy partners (Campbell, 1999), perhaps because they can bask in the reflected glory of these people. In sum, narcissists are more likely to select social environments that allow them to display their performances publicly, ideally in competition with others. These settings are potentially more accepting and reinforcing of narcissistic status strivings.

Source: The “Why” and “How” of Narcissism: A Process Model of Narcissistic Status Pursuit1

Consistent with the self-orientation model, Study 5 provided an empirical demonstration of the mediational role of self enhancement in narcissists’ preference for perfect rather than caring romantic partners. Furthermore, these potential romantic partners were more likely to be seen as a source of self-esteem to the extent that they provided the narcissist with a sense of popularity and importance (i.e., social status). Narcissists’ preference for romantic partners reflects a strategy for interpersonal self-esteem regulation. Narcissists also were attracted to self-oriented romantic partners to the extent that these others were viewed as similar. The mediational roles of self-enhancement and similarity were independent. That is, narcissists’ romantic preferences were driven both by a desire to gain self-esteem and a desire to associate with similar others.

Narcissism has been linked with the materialistic pursuit of wealth and symbols that convey high status (Kasser, 2002; Rose, 2007). This quest for status extends to relationship partners. Narcissists seek romantic partners who offer self- enhancement value either as sources of fawning admiration, or as human trophies (e.g., by possessing impressive wealth or exceptional physical beauty) (Campbell, 1999; Tanchotsrinon, Maneesri, & Campbell, 2007)

Source: The Handbook of Narcissism And Narcissistic Personality Disorders3

Narcissists are looking for partners who can provide them with self-esteem and status. How can a romantic partner provide status and esteem? First, he or she can do so directly: a romantic partner who admires me and thinks that I am wonderful elevates my esteem. Second, he or she can do so indirectly through a basic association: my partner is beautiful and popular, therefore I am too. This indirect esteem generation is clear from a range of social psychological research, from the self-evaluation maintenance (SEM) model (Tesser, 1988) to Basking in Reflected Glory (BIRGing; Cialdini et al., 1976). This indirect esteem provisioning is evident in the term “trophy” partner.

There is good empirical evidence that narcissists like targets who provide esteem and status both directly and indirectly (Campbell, 1999). There is also an important interaction effect. Namely, narcissists like popular and attractive partners, especially when those others admire them. Narcissists, however, are not particularly interested in admiration from just anybody. This finding is inconsistent with the “doormat hypothesis.” Narcissists are not looking for someone they can walk on and who worships them; rather, narcissists are looking for someone ideal who also admires them.

The next question, of course, is what characteristics of a potential partner make them able to provide narcissists with narcissistic esteem? Not surprisingly, what narcissists particularly look for in a partner are physical attractiveness and agentic traits (e.g., status and success). A narcissist’s ideal partner is like a narcissist’s ideal self (recall Freud’s comments): attractive, successful, and admiring of the narcissist. Indeed, in our research, narcissists report that part of the reason that they are drawn to attractive and successful partners is that these people are similar to them (Campbell, 1999).

Dozens more quotations could be added, however the point is obvious: self-enhancement strategies of both narcissism and hypergamy share overlapping features.

The rise of narcissistic behaviors among women is receiving increased attention from academia, particularly with the addition of new variants to the lexicon such as communal narcissism, and vulnerable narcissism, which appear to be preferred female modes of expressing narcissism. A more in-depth survey of narcissism variants among women, and their implications can be read here.

Hypergamy, as an evolutionary motivation, doesn’t require a woman to overestimate her own attractiveness and desirability as she seeks to secure high resource/status males. Narcissism, on the contrary, does entail an overestimation by women of their own attractiveness & desirability as they seek to secure high resource/status males.

To discover whether hypergamy or narcissism is at play, one might simply ask a woman to rate her own attractiveness. If she strongly overrates herself, then her mating-up is likely driven by narcissism and is maladaptive. If she rates herself honestly, then her desire to mate up is more likely driven by an adaptive hypergamy. Mating-up today appears largely driven by maladaptive narcissism; therefore any rationalizing or excusing it as “natural” and “adaptive” serves to compound and increase that same culturally-driven narcissism.

A note on terminology:

Sigmund Freud introduced narcissism as a developmental trait that ranged from healthy to unhealthy.5,6 Some evolutionary psychologists posit that a degree of narcissism might be adaptive in the wider evolutionary sense, though this hypothesis (which has zero genetic evidence to confirm it) can only be applied to a limited subset of behaviours before tipping into maladaptive expressions of narcissism as measured by the usual psychometric instruments.7,8,9 Moreover, no one has satisfactorily demonstrated that a mild, non-pathological narcissism is adaptive and belongs to a construct continuum with more pathological narcissism; therefore it is conjecture to claim that narcissism is natural, but that it simply “gets out of hand” at the more extreme end of a hypothesised spectrum.

With these points in mind it’s necessary to differentiate between female self-enhancement as an evolutionary survival strategy, versus female self-enhancement as a maladaptive, narcissistic pathology. The narcissistic self-enhancement we see increasingly demonstrated among women today is not a contributor to evolutionary success; on the contrary it works to undermine family ties, corrode intimate relationships, and is also associated with lowering the birth rate – the exact opposites of conditions required for “adaptive.” Lastly, by differentiating hypergamous self-enhancement from narcissistic self-enhancement we avoid the error of encouraging or excusing narcissism under the banner of it being “natural.”

Maladaptive vs. adaptive versions of self-enhancement

REFERENCES:

[1] Grapsas, S., Brummelman, E., Back, M. D., & Denissen, J. J. (2020). The “why” and “how” of narcissism: A process model of narcissistic status pursuit. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(1), 150-172.

[2] Campbell, W. K. (1999). Narcissism and romantic attraction. Journal of Personality and social Psychology, 77(6), 1254.

[3] Wallace, H. M. (2011). Narcissistic self-enhancement. The handbook of narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder: Theoretical approaches, empirical findings, and treatments, 309-318.

[4] Campbell, W. K., Brunell, A. B., & Finkel, E. J. (2006). Narcissism, Interpersonal Self-Regulation, and Romantic Relationships: An Agency Model Approach.

[5] Freud, S. (2014). On narcissism: An introduction. Read Books Ltd.

[6] Segal, H., & Bell, D. (2018). The theory of narcissism in the work of Freud and Klein. In Freud’s On Narcissism (pp. 149-174). Routledge.

[7] Holtzman, N. S., & Donnellan, M. B. (2015). The roots of Narcissus: Old and new models of the evolution of narcissism. Evolutionary perspectives on social psychology, 479-489.

[8] Holtzman, N. S. (2018). Did narcissism evolve?. Handbook of Trait Narcissism: Key Advances, Research Methods, and Controversies, 173-181.

[9] Czarna, AZ, Wróbel, M., Folger, LF, Holtzman, NS, Raley, JR, & Foster, JD (2022). Narcissism and Narcissistic Personality Disorder: Evolutionary roots and emotional profiles. In TK Shackelford & L. Al-Shawaf (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Evolution and the Emotions. Oxford University Press.

American Woman and Her Dutiful Husband — Observations by Max O’Rell 1903

The following essay on the status of American women was published in the year 1903 by culture critic Max O’Rell. – PW

THE AMERICAN WOMAN—I

A new coat-of-arms for America—The American woman—Her ways—The liberty she enjoys—’Oh, please make me an American woman!’

If I were asked to suggest a new coat-of-arms for the United States of America, I would propose a beautiful, bright, intelligent-looking woman, under the protection of an eagle spreading its wings over her, with the motto: Place aux Dames—’Honour to the Ladies’; or, if you prefer a freer translation, ‘Make room for the Women.’

The Government of the American people is not a republic, it is not a monarchy: it is a gynarchy, a government by the women for the women, a sort of occult power behind the scenes that rules the country.

It has often been said that a wife is what a husband makes her. I believe that the women of a nation are what the men of that nation make them. Therefore, honour to the men of the United States for having produced that modern national ideal — the American woman.

I have been six times all over the United States. I have spent about three years of my life in America, travelling from New York to San Francisco, from British Columbia to Louisiana. If there is an impression that becomes a deeper and deeper conviction every time that I return to that country, it is that the most interesting woman in the world is the American woman.

Now, let us compare her with the women of Europe. The English woman, when beautiful, is an ideal symphony, an incomparable statue, but too often a statue. The French woman is the embodiment of suppleness and gracefulness, more fascinating by her manner than by either her face or figure.

The Roman woman, with her gorgeous development, suggests the descendant of the proud mother of the Gracchi. The American woman is a combination, an ensemble.

I have never seen in America an absolutely, helplessly plain woman. She is always in the possession of a redeeming ‘something’ which saves her. She may be ever so homely (as the Americans say), she looks intelligent, a creature that has been allowed to think for herself, that has never been sat upon. And I know no sight more pleasing than an elderly American woman, with her white hair, that makes her look like a Louis XV. marquise, and an expression which reflects the respect she has inspired during a well and usefully spent life.

When women were born, a fairy attended the birth of every one of them. Each woman received a special gift. The American woman arriving late, the fairies gathered together and decided to make her a present of part of all the attributes conferred on all the other women. The result is that she has the smartness and the bright look of a French woman, and the shapely, sculptural lines of an English woman. Ah! but, added to that, she has a characteristic trait peculiarly her own, an utter absence of affectation, a naturalness of bearing which makes her unique, a national type. There is not in the world a woman to match her in a drawing-room. There she stands, among the women of all nationalities, a silhouette bien découpée, herself, a queen.

Allowed from the tenderest age almost every liberty, accustomed to take the others, she is free, easy, perfectly natural, with the consciousness of her influence, her power; able by her intelligence and education to enjoy all the intellectual pleasures of life, and by her keen powers of observation and her native adaptability to fit herself for all the conditions of life; an exquisite mixture of a coquette without affectation and a blue-stocking without spectacles or priggishness; the only woman, however beautiful and learned she may be, with whom man feels perfectly at his ease—a sort of fascinating good fellow, retaining all the best attributes of womanhood.

Now, if this should sound like an outburst of enthusiasm, please excuse me. I owe to American women such pleasant, never-to-be-forgotten hours that on merely hearing the mention of the American woman I take off my hat.

Of all the women in the world, the American woman is the one who receives the best attentions at the hands of men. The Frenchman, it is true, is the slave of his womankind, but he expects her to be his thorough partner—I mean, to share with him his labours as well as his pleasures. The American man is the most devoted and hard-working husband in the world. The poor, dear fellow! He works, and he works, and he works, and the beads of perspiration from his brow crystallize in the shape of diamonds all over the ears, the fingers and the neck of his interesting womankind.

He invites her to share his pleasures, but he saves her the trouble of sharing his anxieties. The burden of life from seven in the morning till seven in the evening rests on his shoulders alone.

Yet, in spite of all this, I have seldom discovered in American women the slightest trace of gratitude to men. The American woman expects a triumphal arch to be erected over each doorway through which she has to pass—and she gets it.

Well, she deserves it.

Almost throughout the length and breadth of the United States, you hear of women seeking to extend the sphere of their influence, women dissatisfied with their lot. But there is no satisfying spoiled children. If they see the moon reflected in a pail of water, they must have it.

I am perfectly convinced that the American woman has secured for herself the best, the softest berth that it was possible to secure in this world.

Let me finish by repeating an exclamation I uttered after my first visit to the United States, twelve years ago: ‘If I could choose my sex and my birthplace, I would shout to the Almighty at the top of my voice: “Oh, please make me an American woman!”‘

THE AMERICAN WOMAN—II

She walks first, Jonathan behind her—The educational system of America explains the idiosyncrasies of the American woman.

The first time that I was in America, some twelve years ago, I one day mentioned to a newspaper reporter that I could not find a cup of tea to please me anywhere in America. The next day a paragraph about me appeared in the paper, headed, ‘Max is going to abuse everything in America.’

A few days later I had an opportunity to mention to another reporter that, however bad meals were in some hotels in the small cities, I could everywhere get a cup of coffee quite as good as in France, if not even better. The next day a paragraph appeared headed: ‘Max wants our dollars.’

I have many times lectured in the United States on women, including a sketch on American women. After the lecture I have generally been introduced to some ladies of the audience, who kindly expressed the desire of shaking hands with me.

Almost every time one or two have taken me aside, and said: ‘I have read in your books and your magazine articles and heard in your lectures all you have to say about American women; but now, tell me, what do you really think of them?’

My dear ladies, there are some men who do occasionally speak the truth, or what they believe to be the truth, and who do say what they mean, and mean what they say.

The English, long ago, warned me that I would not be able to do in America what I had successfully done in England, because the Americans, they said to me, were much more susceptible and sensitive than the English. They were mistaken.

No doubt the Americans had resented, and justly, too, the criticisms of Trollope and Dickens (the latter had to write a permanent apology in the preface of ‘Martin Chuzzlewit’). Criticism that never offends, and praises that never flatter, are, I believe, everywhere acceptable when they are taken in the spirit of fairness and good-humour in which they are expressed. I believe, and firmly believe, the American women to be the most interesting and the most brilliant women in the world, and I do not see why I could not proclaim it from the house-tops if I like, even in America.

They are picturesque, vivacious, natural, stylish, smart, clever, unconventional, and the best educated. They are typical, perfectly labelled.

Take me to a drawing-room in Paris or in London, and, without being introduced to anyone, I think I should be able to pick out all the American women in the room.

Once, after a lecture in England, I received the card of a young American lady who wished to speak to me. She came and brought in her mother, and also a man, who all the time stood in the rear. When we parted, she left, followed by her mother. Then I discovered the man, who said to me most meekly, ‘I’m the father.’ Poor dear man! he looked so small as he emerged from the background!

I cannot help thinking that there exists in some American women a little mild contempt for that poor creature that is called a man.

And how is that in a country where the women receive such delightful, and, for that matter, well-deserved attentions at the hands of the men, and that throughout the length and breadth of the country?

Well, I think the educational system of America explains the phenomenon.

In Europe the sexes are kept apart in youth—I mean at school, and, in France especially, young boys and young girls entertain for one another very strange feelings, most of them founded on ignorance.

In Europe even now the education received by girls cannot be compared to the education received by boys. That’s being changed now—some say improved. H’m! we shall see.

It was not a long time ago that, in England and in France, when a girl could read, write, add, and subtract, name the capitals of Europe, and play ‘The Maiden’s Prayer’ on the piano, her education was finished; she was prepared for the world and ready for her husband—and her neighbours.

Very often I have been invited to be present at the distribution of prizes in large English public schools and colleges. When I was in a girls’ school, I never once failed to hear those poor girls told, and by men, too, that practically the only thing they should think about was to prepare to become one day good wives and good mothers.

I have been many times present at the distribution of prizes in boys’ schools in England, and I know that I never heard those boys told that now and then they might think of preparing to become one day decent fathers and tolerable husbands.

In America things are different. In every grade of educational life, among the masses of the people, boys and girls are educated together, side by side; on each bench a boy, a girl, a boy, a girl.

Now, the official statistics of the Education Department declare that in every State of the Union the number of diplomas and certificates obtained by girls is larger than the number obtained by boys.

When I heard that statement, I said this to myself (kindly follow my little argument): ‘Is it not just possible that the young American boys, when they saw what those girls next to them could do, said to themselves, “Heaven! who would have thought so?”‘

Is it not also possible that the young American girls, when they saw what those boys next to them could do, exclaimed, ‘Good gracious! is that all?’

Does not that, to a certain extent, explain to you the respect that young boys acquire at school for young girls, and perhaps, also, that little mild absence of respect that girls get for boys? I believe there is something in it.

Ah, my dear European men, who clamour at the top of your voices for the higher education of women, be careful! You will be found out, and, like your fellow-men of America, by-and-by you will have to take the back-seat.

THE AMERICAN WOMAN—III

Opinions and impressions — An answer to criticism.

Whenever I read a testimonial given to a candidate for some vacant post, I invariably take it for granted that the candidate does not possess the virtues, attainments, or qualities which are not mentioned in that testimonial.

This must have evidently been what that clever American writer, Mrs. Winifred Black, thought when she read an article of mine on American women which appeared in the Editorial section of the New York Sunday Journal some time ago. My admiration for American women is, I think, pretty well known to the public, but more particularly to my most intimate friends. In that article I said: ‘I firmly believe the American women to be the most fascinating, the most interesting, and the most brilliant women in the world; and I do not see why I could not proclaim it from the housetops, if I like, even in America.’ And after mentioning the respect which woman inspires in American men of all classes, the liberty she enjoys, the attentions that are lavished upon her, I concluded the article by exclaiming: ‘If I could choose again my sex and my birthplace, I would shout to the Almighty at the top of my voice: “Oh, please make me an American woman!”‘

‘Now,’ exclaims Mrs. Winifred Black, ‘look between the words of that cleverly constructed sentence, and he who runs may read that Max O’Rell means to say in the still small voice of his innermost convictions: “Make me anything on earth except an American man!”‘

‘And,’ she goes on, ‘our friend is covering himself with well-earned glory, telling us all about the American woman. “She is beautiful, clever, adored, a queen”; but he does not mention that she is good, honest, true, unselfish, loving. Not a syllable about her heart and her soul. Do you know why? Because Max O’Rell thinks that the American woman has neither heart nor soul.’

Oh, oh! my dear lady, how quickly you set to work and jump at conclusions!

Mrs. Winifred Black evidently believes that when I propose the toast, ‘The American ladies—God bless them!’ I whisper under my breath all the time: ‘The gentlemen—God help them!’

Now, madam, let me tell you that this is witty, smart, but not fair criticism. If I ever should have the honour of being introduced to you, I would say to you: ‘When a foreigner attempts to describe the character of the people he visits, he either receives impressions, if he keeps his eyes fairly well open, or he forms opinions, if he resides in that country for a long time or happens to be a born conceited idiot. Impressions are not opinions. Impressions mean nothing more than this: how a nation strikes a foreigner who pays a short visit to it. You see a town for a day, you meet a person for ten minutes. That town, that person, has left an impression on you, but you hold no opinion on either.

I know a charming little book on Denmark, honestly entitled by its author, ‘A Week in Denmark.’ Now, surely you would not expect to find in such a book a study of the institutions of Denmark or opinions on the idiosyncrasies of the Danish people. You would not expect the writer to tell you whether the Danish women have or have not a heart and a soul. No, you would expect to find an impression such as the following, which I find in that delightful, chatty, and unpretentious little volume: ‘The Danish women wear the national colours of France—blue eyes, white complexion, and red lips.’ I have been six times in the United States. I have seen the whole continent from New York to San Francisco, from British Columbia to Louisiana, but all the time I have been on the move, seldom spending two days in the same town. How could I form opinions worth repeating?

The qualities which, for instance, I may have discovered in American women are superficial ones—I mean outward ones, those that would be noticed by the casual visitor—brilliancy, conversational power, beautiful figures, attractive, intelligent faces, smartness in dress, gait, and carriage. To get at their hearts and their souls, I should have to settle in the country, and for years and years live among the people.

THE HUSBAND OF THE AMERICAN WOMAN

The telephone and the ticker—The most useful of domestic animals—Money-making—Loneliness of the women—A reminiscence of Chicago.

On the whole, I believe that there is no country where men and women go through life together on such equal terms as in France. The wife follows her husband everywhere; she is the companion of his pleasures as well as of his hardships. She works with him, takes her vacation with him, and when they have amassed a little fortune that insures independence, they knock off work together and enjoy life quietly for the rest of their days. In business, the wife is the clerk of her husband, often his cashier, always his partner. She is consulted by him in the investment of their savings. It is a little firm—Monsieur, Madame and Co.

In England, the wife does not share the hardships of her husband, and not always his pleasures. She is seldom consulted in important matters.

What often astonishes us in Europe is to see a crowd of handsome and clever women, whom America sends to brighten up society, and who reappear in London and Paris every year with the regularity of the swallows. The London season, from the beginning of May to July 25, the Paris season, from the beginning of April to June 10, are absolutely run by them. You meet them everywhere, at dinner-parties, ‘At Homes,’ and the play. You conclude that they must be married, because they are styled Mrs. and not Miss, but whether they are wives, widows, or divorcées, you rarely think of inquiring, and you go on enjoying their society, even their friendship, year after year, without knowing whether there exists, somewhere in America, a Mr. So-and-so or not.

It was in America only, on calling on my lady friends whose acquaintance I had made in Europe, that I discovered the existence of their husbands. I found them very much alive, having for the companions of their joys and sorrows the telephone and the ticker.

Now, an impression (not an opinion, much less a conviction) to be formed from all this is that the American woman, with all her physical beauty and intellectual attainments, is not always a woman whose characteristic traits are devotion, unselfishness, and self-sacrifice. But it is not her fault if this should be the case, and I have no reason to suppose that it is. In a community, woman is what man makes her. So long as men’s first consideration is business and money-making, so long as they consider clubs the proper place to seek relief in from the pursuits and hardships of everyday life, so long as wives are practically left to themselves to make the best of the long leisures of the day, the women will study how best they can arrange for themselves a life of comfort, ease and pleasure.

Is there any other country where you will find women able to enjoy life without the companionship of men? They have come to an understanding among themselves. They will have lunch, dinner-parties, where no male guest will be seen, and they will have a grand time. They try to please each other, and an American woman will use as much coquetry to win a woman as a French woman will use to win a man. Is there any other country where you see so many women’s clubs?

Women’s clubs? The idea!

Yet that American woman has male friends. She is a delightful chum and good fellow, the only woman in the world who can have such male friends, ‘pals’ without the least misconstruction, the least objectionable whisperings on the subject. She calls those male friends by their Christian names in speaking of them, although she invariably mentions her husband as Mr. John B. Smith.

The American men are the most devoted of husbands, but they are not under the influence of their women. They indulge them in all their whims and luxuries, but their status in life is to be their women’s husbands—I will not say upper servants, but domestic animals, not pets, of undeniable usefulness, who work at the sweat of their brows to keep in luxury the most lovely, interesting and expensive womankind in the world.

Some years ago, I was spending a Sunday afternoon in the house of a young married man in Chicago who, I was told, possessed twenty millions. The poor fellow! It was the twenty millions which possessed him. He had a most beautiful and interesting wife, and the loveliest little girl of three or four years of age that I ever set my eyes on. That lovely little girl was kind enough to take to me at once—there’s no accounting for taste! We had a little flirtation in the distance at first. By-and-by, she came toward me, nearer and nearer, then she stopped in front of me, and looked at me, hesitating, with her finger in her pretty little mouth. I knew what she wanted, and I said to her: ‘That’s all right; come on.’ She jumped on my knees, settled herself comfortably and asked me to tell her stories. I started at once. Now, you understand, I was not allowed to stop; but I took breath, and I said to her:

‘Does not your papa tell you long stories on Sundays?’

That lovely little round face grew sad and quite long.

‘Oh no,’ she said; ‘papa is too tired on Sundays.’

A few weeks after I left Chicago that man was taken ill with a disease not uncommon in America, a disease that starts at the top of your head and takes two or three years to kill you in a lunatic asylum, among drivelling idiots and imbeciles.

A couple of years later, being in Chicago again, I made inquiries and learned that the poor fellow was expected to exist a few weeks, perhaps a few months longer.

What a pity, I thought, that beautiful woman had not enough influence over that good man to stop him!

Do not offer me twenty millions at that price. No twenty millions can cure the disease which afflicted that American.

Put a little girl of three on my knees on Sundays, and I will tell her stories from sunrise and go on till sunset, even if I thus run the risk of being prosecuted by the Lord’s Day Observance Society.

‘GYNOCENTRISM’ – a review by Aman Siddiqi

The following review of the concept gynocentrism is excerpted from A Clinical Guide to Discussing Prejudice Against Men, by Aman Siddiqi:

Gynocentrism

Gynocentrism refers to an exclusive or predominant focus on women or women’s interests (Wright, 2014; Wright & Elam, 2017). It is a form of positive prejudice towards women that results in negative consequences for men. Gynocentrism encourages male gender blindness by focusing attention and concern onto women, causing men and the issues they face to be overlooked or minimized. This, in turn, reinforces the gender disparity illusion. Since men’s issues are rarely discussed in the media or highlighted by organizations, the public assumes they do not exist. While addressing women’s issues is also meaningful, gynocentrism refers to the tendency for academia, the media, government and non-profit agencies to focus all, or nearly all, attention for gendered issues on women and girls.

First, issues that impact women occupy the majority of gendered discussions. They are discussed by the media and investigated by academics. The public is inundated with examples of issues women face. This disproportionate attention keeps the public unaware of men’s issues. In addition, instances of prejudice that are known by most people may be assumed to be of little importance because they are rarely discussed. Exclusionary attention to women’s issues also reveals that those in positions of authority do not deem instances of male suffering worthy of attention. This discourages the general public from paying those instances attention themselves. For example, ignorance of the issues men face has been suggested as one reason for the decline in male psychologists (Bottom et al., 2014).

Second, government agencies, academic research, and non-profit agencies dedicate the majority of their resources on gendered issues to women and girls. Numerous government and non-governmental agencies, such as the United Nations, World Bank, and International Monetary Fund, have divisions devoted to ending violence, improving health, encouraging education, and sponsoring entrepreneurship, exclusively for women. These agencies are replicated in countries around the world. In addition, innumerable non-profit organizations are either dedicated exclusively to women, or the gendered programs within larger organizations are dedicated to women.

The gynocentric view that only women deserve assistance is a consequence of the gender disparity illusion and the compassion void. Men’s suffering is either minimized, reframed to appear nongendered, or blamed on men themselves. The biased allocation of resources impacts the necessary services men and boys require, such as domestic violence shelters, health and wellness centers, educational programs and scholarships, and economic development programs. Similarly, academic research primarily focuses on gendered issues that women face. Dozens of journals are dedicated exclusively to women, and most gendered topic publications focus on women’s issues. Even publications in the journal Psychology of Men & Masculinity often focus on women, such as male sexual objectification of women (Mikorski &Szymanski, 2016) and male perpetrated dating violence (McDermott et al., 2017). Issues that men face are often ignored, even by those in the field of the psychology of men.

Third, gynocentrism results in the gendering of non-gendered issues. While some issues affect men or women disproportionately, many issues are non-gendered. In this case, there is no meaningful differentiation based on gender. However, an issue may be framed in a manner so it appears to disproportionately affect women. This serves to indirectly deny the equal suffering men experience by focusing all, or the majority, of resources and awareness on women’s experience of a non-gendered issue.

Gynocentrically gendering a nongendered issue may be facilitated by highlighting relevant statistics regarding only female victims. Even though the number of men and women impacted by an issue may be roughly the same, some publications only describe the impacts to women. This may cause the public to assume women are disproportionately impacted and deserve the majority of resources, even if it is not explicitly stated. The public may also assume men are not harmed by the issue simply because only the experiences of women are discussed. This is enabled by the male gender empathy gap. The suffering men experience through a non-gendered issue may be disregarded by researchers, so only the female victims are recognized.

An issue may also be gendered through gynocentric reframing. Women who experience a phenomenon may be described using positive terminology while men, impacted by the same issue, are described negatively. For example, female prisoners were referred to as “victims” of their environment, while male prisoners were called “violent” in the same article (Kearns, 2019). Attributions of malicious intentionality have been projected onto male perpetrators of domestic violence and sexual assault, while female perpetrators are described as being compelled by external forces into their actions (M. P. Johnson, 1995). This is an example of the ultimate attribution error, in which negative in-group (female) behaviors are attributed to external factors, but negative out-group (male) behaviors are attributed to personal characteristics (Pettigrew, 1979). This form of gynocentric reframing encourages the denial of victimhood, since causality for negative male behaviors is not linked to the social environment.

The dedication of public and private agencies to women, described in item two above, also encourages the gynocentric use of statistics. For example, the Department of Justice’s Office on Violence Against Women may feel justified in only publishing data regarding female victims of domestic violence and sexual assault since their mandate is to focus on women. This creates an “echo chamber” in which only statistics on women are published, leading people to believe an issue exclusively or predominately impacts women. This, in-turn, encourages resources and agencies be designed disproportionately for women, such as the Office on Violence Against Women.

Similarly, the United Nations’ Girls’ Education Initiative published a report detailing various barriers to girls’ education around the world (UNGEI, 2007). Items in the report include: poverty, social exclusion due to ethnicity, poor school conditions, overcrowded classrooms, and a lack of qualified teachers. The report claims that textbooks that promote gender stereotypes, inadequate water and sanitation, and violence near schools “are barriers that affect girls’ education in particular” (UNGEI, 2007, p. 3). However, these are all general barriers to education that impact boys and girls equally. The male gender empathy gap may cause the authors to disregard their impact on boys.

Fourth, gynocentric laws solidify institutional prejudice into society by creating differing requirements and protections for male and female citizens of the same country. For example, in the United States, the mandatory registration for selective service applies exclusively to men (Selective Service Registration, 2019). Furthermore, the male-only military draft is actively enforced in other countries around the world. As discussed further in the section entitled, “Examples of Prejudice Against Men,” numerous U.S. States, as well as foreign countries, specifically define rape as requiring a female victim. Laws, such as the Violence Against Women Act, provide government resources for women (Violence Against Women Act of 1994, 1994) and laws, such as the Female Genital Mutilation Act, define criminal actions as illegal only if the victim is female (Female Genital Mutilation Act, 1996). Similarly, the Indian penal code provides protection to wives that is not afforded to husbands (The Criminal Law (Second Amendment) Act 1983, 1983). This is only a sample of gendered laws that do not offer the same protection to, or enforce the same requirements on, all citizens equally.

Fifth, a gynocentric perspective may be used when interpreting gendered issues. When attributing meaning to events, evaluating the costs and benefits of gendered norms, or deciding who has control or agency in a situation, the perspectives of men are often overlooked or openly denied. While female perspectives are also meaningful, they may be taught in a manner which precludes any other views. A gynocentric bias has also been pushed onto descriptions of men’s own actions and desires. In this way, men’s own intentions, beliefs, and feelings are replaced with what others claim they intend, believe, and feel. This is an example of “speaking for men,” described in the section entitled, “Maintenance of the Acceptability of Prejudice Against Men.”

Similarly, a gynocentric perspective can bias the judicial system, resulting in unequal application of the law. For example, studies have shown men are given longer sentences for the same crime (Crew, 1991; Curry et al., 2004) and following a divorce, men are only made the custodial parent 17.5% of the time (Grall, 2016, p. 2013). The gynocentric perspective also impacts the mental health field. For example, Zander Keig is a transgender male who transitioned at age 39 (Bahrampour, 2018, Para. 15). Even though he is a clinical social worker, he admits that prior to his transition, he never considered men’s experiences or thoughts. He interpreted every case from a female perspective.

Sixth, a gynocentric viewpoint may give some women a feeling of superiority to men. They may begin to view themselves as deserving of preferential treatment. This can contribute to the belief in the transfer of hardship onto men. Psychological entitlement includes the belief that one deserves valuable possessions, praise, and is superior (W. K. Campbell et al., 2004). A study utilizing a nationally representative sample of 2,723 women and 1,698 men in New Zealand found that women’s endorsement of “benevolent sexism” was correlated (r = .41, p < .01) with psychological entitlement (Hammond et al., 2014). Described further in the section entitled “Maintenance of the Acceptability of Prejudice Against Men,” benevolent sexism is the term used to gynocentrically reframe prejudice in which men are compelled to serve women. Therefore, women who endorse the belief that men should provide them with preferential treatment were more likely to feel entitled. This was also described by Zander Keig, the transgender male mentioned above. He is in a position to compare his treatment by other women for the first 39 years of his life as a woman, to his treatment after transitioning to a male (Bahrampour, 2018). He states that now that he is a man, some women expect him to acquiesce and concede to them by letting them speak first, board a bus first, and let them sit down first. (Bahrampour, 2018).

Gynocentric social norms are still prevalent in modern society. For example, in some communities within the U.S., men are still expected to give up their seats to women, allow them to go before them in line, or provide other forms of preferential treatment. In some countries, this bias is solidified into law. For example, in India the front seating area on some public buses is reserved for women only, while the remaining are general seating. Men are forced to stand while seats are available because they are deemed unworthy of the right to rest. In addition, the general seating area is often occupied by female passengers, since the social norms upon which the regulation is based compel men to give up their seats to female passengers. Bus segregation was declared unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1956 and is considered a quintessential example of Jim Crow segregation (Browder v. Gayle, 1956). However, men face similar discrimination to this day. While not mandated by law in the U.S., these types of expectations still occur. For example, a video was recorded of a woman shouting and berating men on a subway train for not “being a gentleman” and giving her preferential treatment (Diinodiin Edits, 2019), and a similar incident was portrayed on an episode of Seinfeld (Cherones, 1992).

In contemporary society, gynocentrism has made romantic and sexual service to women expected of men. Some television, film, and academic publications teach or imply that it is men’s responsibility to provide romance and sexual satisfaction to a female partner. Men who do not provide romance to women may be portrayed as lazy and self-centered. For example, in an episode of The Big Bang Theory, the character Penny complains that her husband Leonard doesn’t “do anything for her anymore” and has “completely stop[ped] giving a crap” (Cendrowski, 2017). She states he “used to do all these things, like bring me flowers.” Later, she starts an argument with him and states, “since we got married you seem to think you don’t have to try anymore.” At this point, Leonard points out that he has provided all the romantic gestures in their relationship in the past, while she was mainly a recipient. In response, Penny decides to punish Leonard by canceling her vacation with him and taking her friend instead. This sends a message that not only are men obligated to provide romance to women, but if they point out the inequity of their situation, they should be punished.

Similarly, in an episode of Chuck, some characters become suspicious that a woman is cheating on her husband (Chandrasekhar, 2010). They confront the man and state, “I feel that if there is something wrong, it’s your fault.” The man then proceeds to list for them an average day in his life, in which he serves his wife, proving he is a good husband.

Most mornings, I wake up around 6. I pop a towel in the dryer so it’s warm when she gets out of the shower. I’ll whip her up a Belgian waffle or, you know, a goat-cheese omelet. Something easy. After Ellie’s foot rub, I’ll bike to the farmers’ market pick up fresh blueberries, or whatever’s in season. Come home, make her a smoothie. Organic nonfat milk, flaxseed oil. Something to give her a real midday kick-start. Once we’re in bed, post-lavender bath I spend about 20 minutes just watching her sleep.

He does all this while also being an emergency room physician. While the episode may be portraying an exaggerated view of the ideal husband, the premise is based on the overall assumption of romantic service to women. The episode sends the message that if a man does not serve his wife enough, she is justified in cheating on him.

Contemporary media also portrays men as owing sexual service to women. As an example of the agency bias, responsibility for a woman’s sexual enjoyment is attributed to her male partner, while his enjoyment is paid little attention and assumed to be his own responsibility. This expectation is demonstrated most clearly by the term “perform,” used to describe a man’s sexual relations with a woman. Men and women are not described as jointly participating in sexual relations. Instead, men are evaluated on their “performance,” defined by the degree to which they satisfy a female partner. The book She Comes First: The Thinking Man’s Guide to Pleasuring a Woman is a best-selling book that teaches men their job during sexis to satisfy women and provide them pleasure (Kerner, 2009). The author encourages men to derive their enjoyment from the act of serving their partner. He states, “What greater reward could a man ask for?” (Kerner, 2009, p. 20). A man experiencing pleasure himself is framed as selfish.

The author describes sexual intimacy as women receiving pleasure and men providing it. He goes as far as to justify the attack of Lorena Bobbitt against her husband by claiming that she cited his failure to sexually satisfy her as a reason. The gynocentric view of sexuality has become the norm for many in contemporary society. Men may be taught that they are selfish and unworthy unless they spend their sexual encounter focused exclusively on their female partner. On the other hand, women are taught that if they do not enjoy their experience or did not experience an orgasm, they should not look to their own absence of engagement. Instead, women should blame men for not serving them well enough. This was demonstrated by an Amazon reviewer who accused any man of not wanting to read, She Comes First: The Thinking Man’s Guide to Pleasuring a Woman as having too much “pride and ego” (Reviewer, 2018).

The gynocentric belief in male service to women has been enabled through the term chivalry. Historically, the term chivalry encompassed a variety of attributes such as bravery, loyalty, and generosity (Bax, 1913). However, over time chivalry was transformed into male service to women (Alfonsi, 1986). Men may also be shamed into service through accusations of not being a “gentleman;” therefore, equating being a gentleman with serving women. Prejudice against men is concealed by first reframing it as acts of chivalry, then attributing responsibility for the enforcement of chivalrous norms to men.

Positive Female Stereotypes

Gynocentrism also encourages the proliferation of positive female stereotypes. Positive prejudice is projected onto women through a gender-based halo effect. Women may be described as more empathetic, kinder, loving, elegant, honest, trustworthy, and peaceful than men. These stereotypes are used to deny instances of wrongdoing by women, at times shifting blame onto men. For example, domestic violence and sexual assault committed by women against men is often denied or trivialized, leaving male victims without help or recourse.

Studies have revealed that people hold a more positive view of women overall as compared to men. Attitude measures include variables such as how good vs. bad and valuable vs. useless men are compared to women (Eagly & Mladinic, 1994). Participants describe the percentage of each group they believe holds various characteristics, including their own views of how positive or negative those characteristics are. In addition, the affective responses that participants experience in response to men as compared to women are examined. Numerous studies have found that overall, participants hold more positive attitudes, stereotypes, and affective responses (i.e., feelings) towards women than men (Carter et al., 1991; Eagly et al., 1991; Eagly & Mladinic, 1989, 1994; Haddock & Zanna, 1994). This may be evidence of a global halo effect in which women are perceived as better people than men. This has been referred to as the “women are wonderful effect” (Eagly & Mladinic, 1994). This leads to implied negative stereotypes about men, resulting in bias and discrimination. For example, if people are unwilling to believe a woman is guilty of domestic violence, they may assume the victim is either lying or at fault themselves.

Positive prejudice may also be used to claim that women are superior to men in various ways. For example, Hillary Clinton stated that female leaders demonstrate more compassion and understanding than men because they lead “with the heart of a mother” (Zakaria, 2019). Similarly, President Obama explicitly stated that women are “indisputably” better leaders than men, and that the world would be a better place if only women were in leadership positions (Asher, 2019).

The belief in positive stereotypes about women can result in gynocentric projection, in which positive characteristics, or interpretations of actions, are projected onto women without evidence. This is demonstrated by entertainment media’s reluctance to portray evil female characters. Antagonist female characters are often provided a rationale to justify their behavior or are portrayed as a victim of circumstance. For example, in the film What Happened to Monday, the character named Monday is kidnapped in the beginning of the film (Wirkola, 2017). As the plot continues, each of her six sisters is targeted for murder one at a time by government agents. Eventually, the final two surviving sisters discover that Monday was not kidnapped, but in fact betrayed her sisters, allowing them to be murdered. However, instead of allowing a female character to be portrayed as evil or self-serving, the film provides her an excuse. The sisters discover that Monday was pregnant, and she chose to save her baby by having her six sisters murdered. This plot line demonstrates both the unwillingness of society to accept an evil female character, and purports that murdering six people is excusable since she is a mother.

Gynocentric projection is also demonstrated by researchers who project positive qualities onto women to explain negative behavior. For example, it has been alleged that female perpetrated domestic violence is motivated by a desire for “personal liberty” instead of controlling behavior, aggression, and impaired impulse control (Graham-Kevan, 2007b). Similarly, maternal filicide, mothers who kill their own babies, has been explained as either “altruistic,” for the betterment of the child, the result of psychosis, or unintentional (Friedman & Resnick, 2007). Any negative characteristics of the perpetrator herself are assumed to be absent. The only somewhat negative intentions suggested are the mother’s view of the baby as a hindrance, and the mother’s desire for revenge against the child’s father. However, these intentions can be justified respectively as a result of poverty, and the shifting of blame to alleged negative behaviors of the father.

As another example, a study was conducted to replicate Milgram’s famous study of obedience (Milgram, 1963). A sample of 13 men and 13 women were used to test their willingness to shock a puppy as a means of teaching it to solve problems (Sheridan & King, 1972). The voltage administered was increased with each successive incorrect solution. The participants were able to see the puppy’s reaction each time it was shocked. The problem was, in fact, unsolvable. The true purpose of the study was to see if the participants would continue shocking the puppy as the voltage and pain increased. Among the male participants, 7 of the 13 participants continued shocking the puppy until the completion of the experiment. The remaining 5 refused to continue at some point during the experiment. However, all 13 female participants shocked the puppy until the maximum setting.

The experimenters asked a separate set of 45 participants to estimate how men and women would behave in the above experiment. When female participants were asked how far the “average woman” would continue, 86% of female participants said an average woman would not go beyond one-third of the maximum level, and no participants stated the average woman would shock until the maximum. This demonstrates an overly positive belief that women would not cause harm to others. This belief was further demonstrated when this experiment was described in this author’s university’s introductory psychology class. Upon hearing that all the female subjects shocked the puppy to the maximum setting, the class was audibly shocked, confirming the same belief in positive prejudice towards women. Furthermore, the professor offered an explanation for the results, which denied any wrongdoing by the female participants. He told the class that the female participants “felt pressured by the experimenters to continue shocking the puppy,” so it was not really their fault. He implied they were forced into their actions, so the class could maintain their positive prejudice towards women. However, he offered no empirical data to support his explanation. Furthermore, the male subjects would have been equally pressured by the experimenters, yet they resisted. His irrational explanation demonstrates the lengths to which psychologists may go to maintain their positive beliefs towards women.

Terminology

Gynocentric terminology refers to gendered phrases which limit victimhood to women. The use of restrictive, exclusionary phrasing limits people’s empathy by referring to those in need of compassion and assistance as “women” instead of victims. For example, the major piece of U.S. legislation providing resources for domestic violence and sexual assault is named the Violence Against Women Act (U. S. Department of Justice, 2014). Similarly, the United Nations passed the “Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children” (United Nations Human Rights, 2019). The document specifically highlights women as more important victims than men eight times in the document, such as to “combat trafficking in persons, especially women and children” (United Nations Human Rights, 2019, Para. 1).

An article was written in Minority Nurse about microaggressions in nursing against “nontraditional” students. Nontraditional was defined as “over the age of 25, ethnic minority groups, speaks English as a second language, a male, has dependent children, has a general equivalency diploma (GED), required to take remedial courses, and students who commute to the college campus [emphasis added]” (Doctor, 2018, Para. 1). Since 88.6% of nurses in the U.S. are female (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2019a), men are a minority group. However, later in the article the author utilizes an exclusionary definition of microaggressions from the book Microaggressions in Everyday Life: Race, Gender, and Sexual Orientation. The author defines microaggressions as “verbal and nonverbal snubs, insults, putdowns, and condescending messages directed towards people of color, women, the LGBTQ population, people with disabilities, and any other marginalized group [emphasis added]” (Doctor, 2018, Para. 2). This definition specifically lists women as victims of microaggressions and excludes men; even though one of the subjects of the article on nursing is microaggressions against men. When readers and students are taught about microaggressions, they may be primed to assume men will never fall victim to them, or to disregard microaggressions men face as insignificant.

Avoiding gendered terminology has been a major goal of gender studies for decades. For example, the term mankind is replaced with humankind or peoplekind, Time magazine’s “Man of the Year” award was changed to “Person of the Year,” and Cornell’s Society of Hotelmen was changed to the Cornell Hotel Society. Guidelines from the American Psychological Association now encourage the use of a singular form of “they” and “their” in place of “he or she” and “his or hers” (American Psychological Association, 2019). When gendered terminology contributes to excluding women, society makes a point to change it. However, when gendered terminology excludes men, it is often maintained or justified.

For example, at a town hall meeting with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, an individual raised a question about difficulties young people face who desire to volunteer through a charitable religious organization in Canada (The Trudeau Follies, 2018). At the end of her question she stated, “We cannot do free volunteering to help our neighbors in need as we truly desire. So, that’s why we came here today to ask you, to also look into the policies that religious charitable organizations have in our legislation so that it can also be changed, because maternal love is the love that’s going to change the future of mankind. So we’d like you to…” At this point Prime Minister Trudeau interrupted her and said, “We like to say peoplekind, not necessarily mankind;” which was followed by applause. The Prime Minister’s interest in gendered terminology is so strong, his first point when addressing her question about charitable volunteering was to point out her use of the term “mankind.” However, the questioner also stated that “maternal love” is the most important force for change. The use of this gendered phrase went undiscussed. This demonstrates a bias in which gendered terminology that positively impacts women is maintained.

Gynocentric terminology is also used to deny the existence of male victims of domestic violence and sexual assault, excluding them from recognition and services. Victims may be referred to as “women” and perpetrators as “men.” This is often justified by claiming that the majority of those affected are female. However, this argument is based on two fallacies. First, the assumption that women are disproportionately impacted by these crimes is empirically false, described in the section entitled “Examples of Prejudice Against Men.” Second, and more importantly, the percentage of men and women who suffer from these crimes is irrelevant. All victims deserve concern and respect. Even if an individual believes more women are impacted, male victims should never be erased or overlooked. As described above, modern social standards have already determined that excluding a gender through exclusionary terminology is discriminatory. For example, even though 85% of the military is male (Coleman, 2014), and

97.6% of fatalities of active duty U.S. military personnel and Reservists in the Afghanistan and Iraq wars have been male (DeBruyne, 2019), we always use the term “men and women in the military.” Erasing male victims of domestic violence and sexual assault can never be justified by one’s belief that more women are impacted than men. Every individual knows that 100% of victims are not female. Persistence on using the term “women” in place of victims is a statement that male victims do not deserve recognition. This form of gynocentric terminology most clearly demonstrates how an overemphasis on women and women’s issues becomes a form of prejudice against men.

References

American Psychological Association. (2019). Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (Seventh edition). American Psychological Association.

Asher, S. (2019, December 16). Obama: Women are better leaders than men. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-50805822

Alfonsi, S. R. (1986). Masculine submission in troubadour lyric (Vol. 34). Peter Lang Publications.

Bahrampour, T. (2018, July 20). Crossing the divide. Do men really have it easier? These transgender guys found the trugh was more complex. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/local/wp/2018/07/20/feature/crossing-the-divide-do-men-really-have-it-easier-these-transgender-guys-found-the-truth-was-more-complex/?utm_term=.0b551274996f

Bax, E. B. (1913). The fraud of feminism. Grant Richards.

Bottom, T. L., Gouws, D., & Groth, M. (2014). The Influence of academia on men and our understanding of them. New Male Studies, 3(2), 69–92.

Browder v. Gayle, 352 U.S. 903 (1956).

Campbell, W. K., Bonacci, A. M., Shelton, J., Exline, J. J., & Bushman, B. J. (2004). Psychological entitlement: Interpersonal consequences and validation of a self-report measure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 83(1), 29–45. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa8301_04

Carter, J., Lane, C., & Kite, M. (1991). Which sex is more likable? It depends on the subtype. Meeting of the American Psychological Society, Washington, DC.

Cendrowski, M. (2017, January 19). The romance recalibration (10:13). In The Big Bang Theory. Warner Bros. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt6337212/?ref_=ttep_ep14

Cherones, T. (1992, January 8). The Subway (3:!3). In Seinfeld. Castle Rock Entertainment.

Coleman, D. (2014, July 24). U.S. military personnel 1954-2014: The numbers. History in Pieces. https://historyinpieces.com/research/us-military-personnel-1954-2014

Crew, B. K. (1991). Sex differences in criminal sentencing: Chivalry or patriarchy? Justice Quarterly, 8(1), 59–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418829100090911

Curry, T. R., Lee, G., & Rodriguez, S. F. (2004). Does victim gender increase sentence severity? Further explorations of gender dynamics and sentencing outcomes. Crime &Delinquency, 50(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128703256265

DeBruyne, N. F. (2019). American war and military operations casualties: Lists and statistics. Congressional Research Service.

Diinodiin Edits. (2019, February 14). Why are you not being a gentleman (Original) [Video file]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t4VhoyN6jpE