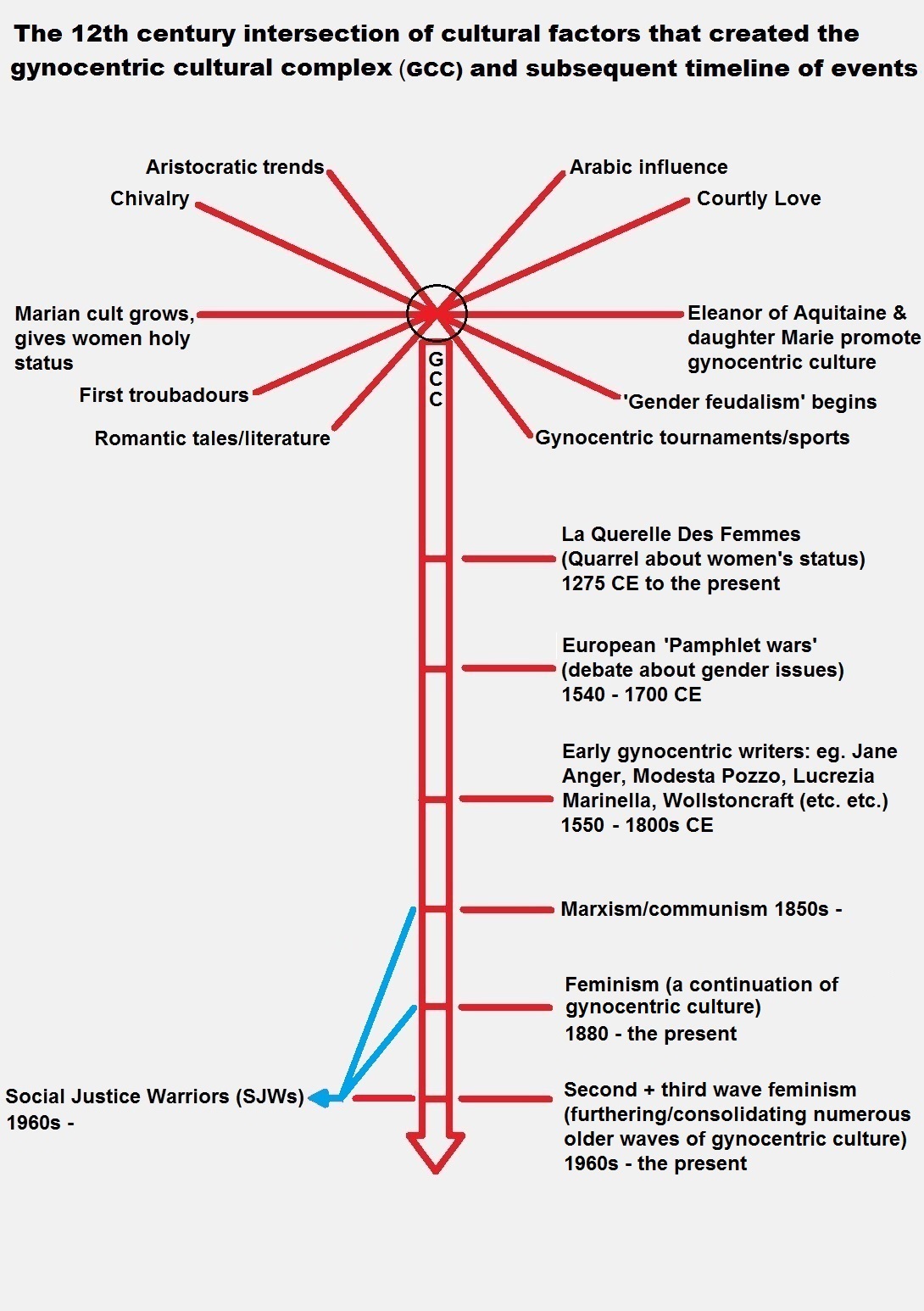

Middle Ages

Gynocentric culture

Did female-centered culture begin in the prehistoric era?

This question is sometimes asked by people who feel that gynocentrism has been around for the entirety of human evolution. The answer to that question is of course yes – isolated examples of gynocentrism have been around throughout human history. However it’s important to make a distinction between individual examples of gynocentrism (that is, individual gynocentric impulses, acts, customs, or events) and gynocentric culture (a pervasive cultural complex that affects every aspect of life). We will never be precise enough to make sense of this subject unless we insist on this distinction between gynocentric acts, and gynocentric-culture.

Gynocentrism:

It’s easy to overstate the import of specific examples of gynocentrism when in fact such examples may be equally balanced, culturally speaking, by male-centered acts, customs, or events which negate the concept of a pervasive gynocentric culture. Here we are reminded of the old adage that one swallow does not make a summer, and that likewise individual gynocentric acts, or even a small collection of such acts, do not amount to a pervasive gynocentric culture.

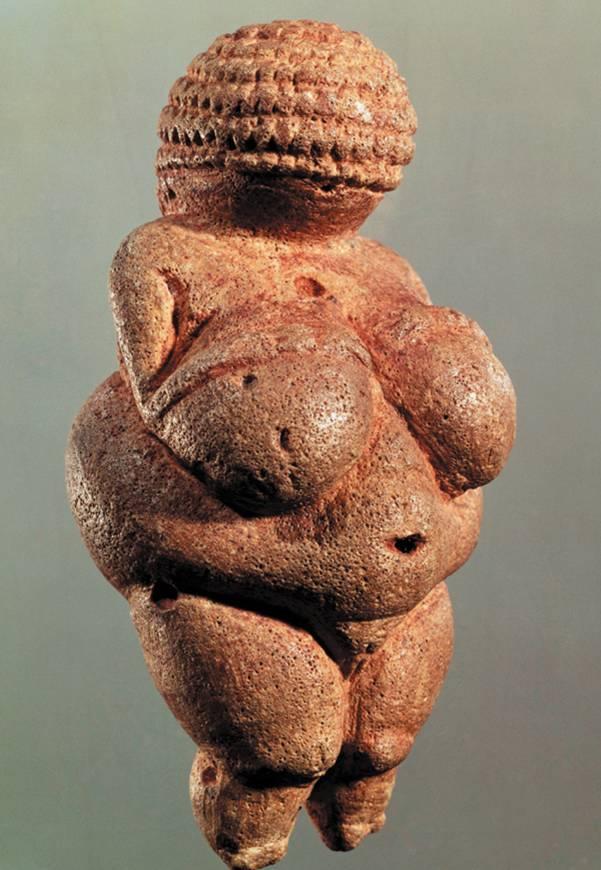

Individual examples of gynocentrism are sometimes misconstrued as representing a broader culture, as seen in the discussion around ancient female figurines which some claim are indications of goddess-worshipping, gynocentric cultures. Not only is the import of the female figurines vastly overstated, the quantity discovered is potentially exaggerated according to leading feminist archeologists:

“Quantitative analyses of Upper Paleolithic imagery make it clear that there are also images of males and that, by and large, most of the imagery of humans-humanoids cannot readily be identified as male or female. In fact, no source can affirm that more than 50 per cent of the imagery is recognizably female.” [Ancient Goddesses]

Even if the majority of these figurines had proven to be female, this wouldn’t indicate a gynocentric culture any more than would statues of the goddess Athena and the Parthenon built in her honor indicate that ancient Athens was a gynocentric city – which it clearly was not.

Archeologists discovered stencils of female hands in ancient caves, created by the practice of spraying mud from the mouth onto a female hand. Some were led to surmise, without evidence, that those same hands served as authorship of the animals that were also painted on the cave walls. Additionally, these archeologists assumed that the presence of female hand images not only meant that women painted the more complex cave art but that the entire ancient world “must have” consisted of a completely gynocentric culture. These assumptions show the dangers of allowing imagination to depart too far from the evidence.

Further examples of overreach are the citing of fictional material from classical era, such as Helen of Troy (a Greek myth), or Lysistrata (a Greek play) as proof of gynocentric culture; unfortunately these examples are about as helpful for understanding gynocentrism as would be the movie Planet of the Apes to future researchers studying the history of primates.

Gynocentric culture:

A cultural complex refers to a significant configuration of culture traits that have major significance in the way people’s lives were lived. In sociology it is defined as a set of culture traits all unified and dominated by one essential trait; such as an industrial cultural complex, religious cultural complex, military cultural complex and so on. In each of these complexes we can identify a core factor – industry, religion, military – so we likewise require a core factor for the gynocentric cultural complex in order for it to qualify for the title. At the core of the gynocentric cultural complex is the feudalistic structure of lords and vassals, a structure which eventually became adopted as a gender relations model requiring men to serve as vassals to women. C.S. Lewis called this restructuring of gender relations ‘the feudalisation of love’ and rightly suggested that is has left no corner of our ethics, our imagination, or our daily life untouched.

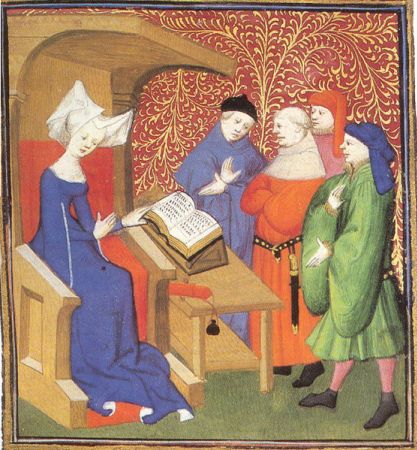

The feudalisation of love was not something seen in pre-medieval times, let alone in the Paleolithic era when feudalism simply didn’t exist. For example, we have not yet seen a cave painting equal to this art from the Middle Ages showing a male acting as subservient vassal to a dominant woman who leads him around by a neck halter.

In summary, it appears everyone agrees that examples of gynocentric acts have existed throughout human history. The question is not whether an act occured but whether or not it was part of a more dominant culture of gynocentrism. We are interested not in when some gynocentric act was recorded but in when the larger gynocentric cultural complex (GCC) began, on which point there appear to be three main theories:

- Ancient Genesis

- Medieval Genesis

- Recent Genesis

This website provides evidence that clearly favors medieval genesis, as there is simply not enough evidence for it in ancient culture beyond scattered examples of gynocentrism. In fact what we do know of classical civilizations appears to favour the reverse conclusion – that these were patently androcentric cultures that held sway globally until the 12th century European revolution.

The Spirit of Chivalry, by Sir Walter Scott (1818)

The following excerpts describing gynocentric-chivalry are taken from Sir Walter Scott’s 1818 essay in the volume Essays on Chivalry, Romance, and the Drama

* * *

The main ingredient in the spirit of Chivalry, second in force only to the religious zeal of its professors, and frequently predominating over it, was a devotion to the female sex, and particularly to her whom each knight selected as the chief object of his affection, of a nature so extravagant and unbounded as to approach to a sort of idolatry. The original source of this sentiment is to be found, like that of Chivalry itself, in the Customs and habits of the northern tribes who possessed, even in their rudest state, so many honourable and manly distinctions, over all the other nations in the same stage of society. The chaste and temperate habits of these youth, and the opinion that it was dishonourable to hold sexual intercourse until the twentieth year was attained, was in the highest degree favourable not only to the morals and health of the ancient Germans, but must have contributed greatly to place their females in that dignified and respectable rank which they held in society.

____________________________

Amid the various duties of knighthood, that of protecting the female sex, respecting their persons, and redressing their wrongs, becoming the champion of their cause, and the chastiser of those by whom they were injured, was represented as one of the principal objects of the institution. Their oath bound the new-made knights to defend the cause of all women without exception ; and the most pressing way of conjuring them to grant a boon was to implore it in the name of God and the ladies. The cause of a distressed lady was, in many instances, preferable to that even of the country to which the knight belonged. Thus, the Captal de Buche, though an English subject, did not hesitate to unite his troops with those of the Comte de Foix, to relieve the ladies in a French town, where they were besieged and threatened with violence by the insurgent peasantry.

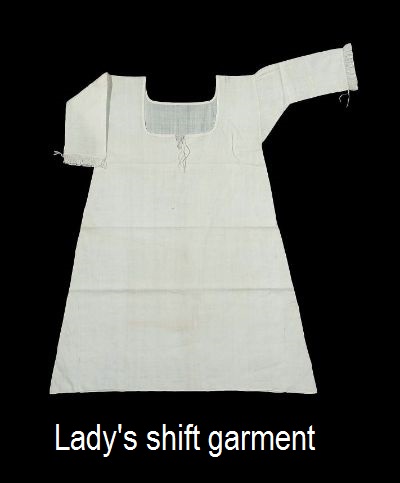

The looks, the words, the sign of a lady, were accounted to- make knights at time of need perform double their usual deeds of strength and valour. At tournaments and in combats, the voices of the ladies were heard like those of the German females in former battles, calling on the knights to remember their fame, and exert themselves to the uttermost. “Think, gentle knights,” was their cry, “upon the wool of your breasts, the nerve of your arms, the love you cherish in your hearts, and do valiantly for ladies behold you.” The corresponding shouts of the combatants were, “Love of ladies! Death of warriors! On, valiant knights, for you fight under fair eyes? Where the honour or love of a lady was at stake, the fairest prize was held out to the victorious knight, and champion from every quarter were sure to hasten to combat in a cause so popular. Chaucer, when he describes the assembly of the knights who came with Arcite and Palemon to fight for the love of the fair Emilie, describes the manners of his age in the following lines;

“For every knight that loved chivalry,

“For every knight that loved chivalry,

And would his thankes have a passant name,

Hath pray’d that he might ben of that game,

And well was him that thereto chusen was.

For if there fell to-morrow such a case,

Ye knowen well that every lusty knight

That loveth par amour, and hath his might,

Were it in Engellande, or elleswhere,

They wold hir thanked willen to be there.

To fight for a lady! Ah! Benedicite,

It were a lusty sight for to see.”

It is needless to multiply quotations on a subject so trite and well known. The defence of the female sex in general, the regard due to their honour, the subservience paid to their commands, the reverent awe and courtesy, which, in their presence, forbear all unseemly words and actions, were so blended with the institution of Chivalry as to form its very essence. But it was not enough that the “very perfect, gentle knight,” should reverence the fair sex in general. It was essential to his character that he should select, as his proper choice, “a lady and a love,” to be the polar star of his thoughts, the mistress of his affections, and the directress of his actions. In her service, he was to observe the duties of loyalty, faith, secrecy, and reverence. Without such an empress of his heart, a knight, in the phrase of the times, was a ship without a rudder, a horse without a bridle, a sword without a hilt ; a being, in short, devoid of that ruling guidance and intelligence, which ought to inspire his bravery, and direct his actions. The least dishonest thought or action was, according to her doctrine, sufficient to forfeit the chivalrous lover the favour of his lady.

It seems, however, that the greater part of her charge concerning incontinence is levelled against such as haunted the receptacles of open vice ; and that she reserved an exception (of which, in the course of the history, she made liberal use) in favour of the intercourse which, in all love, honour, and secrecy, might take place, when the favoured and faithful knight had obtained, by long service, the boon of amorous mercy from the lady whom he loved par amours.In these extracts are painted the actual manners of the age of Chivalry. The necessity of the perfect knight having a mistress, whom he loved par amours, the duty of dedicating his time to obey her commands, however capricious, and his strength to execute extravagant feats of valour, which might redound to her praise, –for all that was done for her sake, and under her auspices, was counted her merit, as the victories of their generals were ascribed to the Roman Emperors— was not a whit less necessary to complete the character of a good knight.

__________________________

On such occasions, the favoured knight, as he wore the colours and badge of the lady of his affections, usually exerted his ingenuity in inventing some device or cognisance which might express their love, either openly, as boasting of it in the eye of the world, or in such mysterious mode of indication as should only be understood by the beloved person if circumstances did not permit an avowal of his passion. The ladies, bound as they were in honour to requite the passion of their knights, were wont, on such occasions, to dignify them by the present of a scarf, ribbon, or glove, which was to be worn in the press of battle and tournament. These marks of favour they displayed on their helmets, and they were accounted the best incentives to deeds of valour. The custom appears to have prevailed in France to a late period, though polluted with the grossness so often mixed with the affected refinement and gallantry of that nation.

On such occasions, the favoured knight, as he wore the colours and badge of the lady of his affections, usually exerted his ingenuity in inventing some device or cognisance which might express their love, either openly, as boasting of it in the eye of the world, or in such mysterious mode of indication as should only be understood by the beloved person if circumstances did not permit an avowal of his passion. The ladies, bound as they were in honour to requite the passion of their knights, were wont, on such occasions, to dignify them by the present of a scarf, ribbon, or glove, which was to be worn in the press of battle and tournament. These marks of favour they displayed on their helmets, and they were accounted the best incentives to deeds of valour. The custom appears to have prevailed in France to a late period, though polluted with the grossness so often mixed with the affected refinement and gallantry of that nation.

Sometimes the ladies, in conferring these tokens of their favour, saddled the knights with the most extravagant and severe conditions. But the lover had his advantage in such cases, that if he ventured to vencounter the hazard imposed, and chanced to survive it, he had, according to the fashion of the age, the right of exacting, from the lady, favours corresponding in importance.

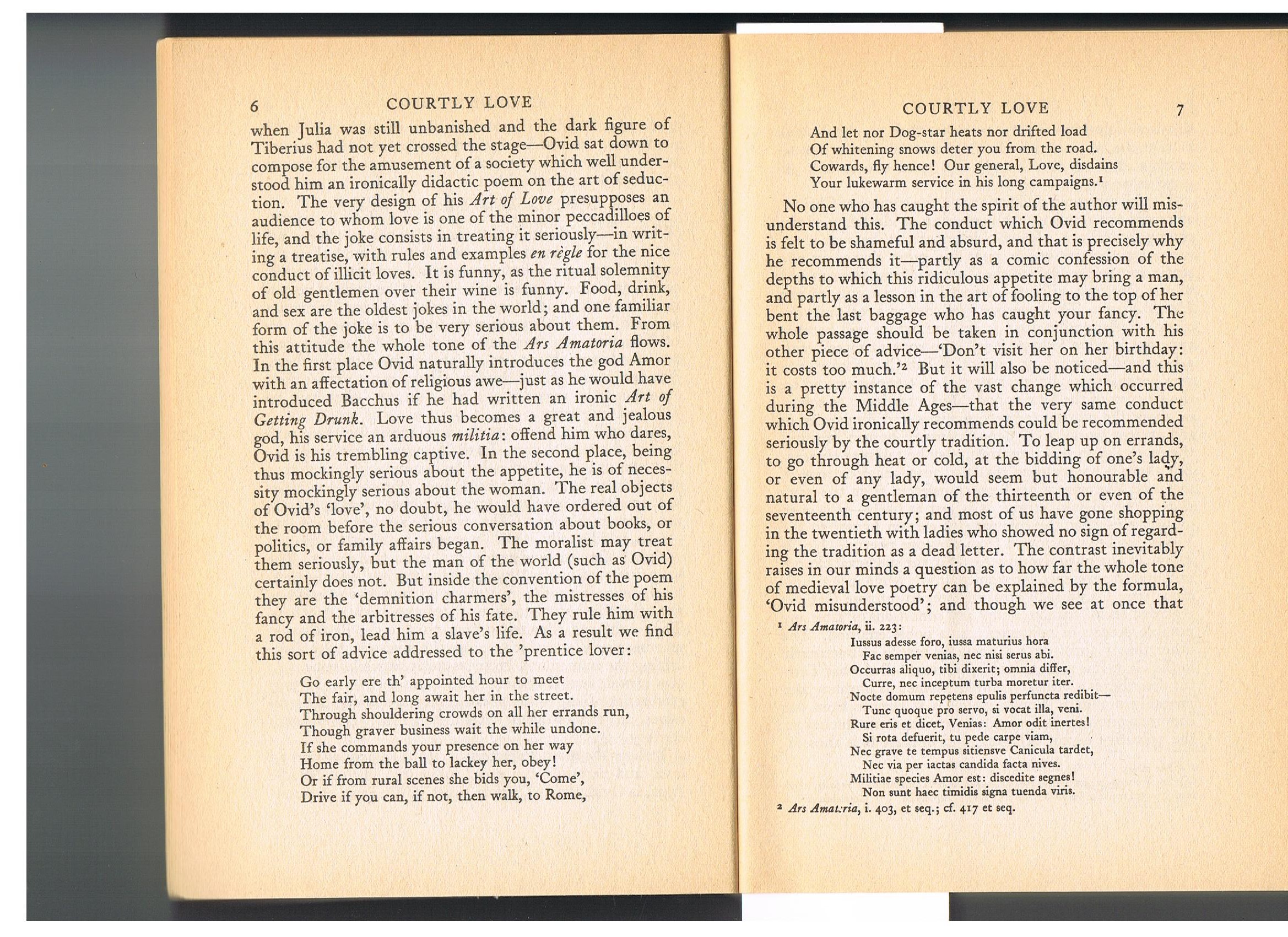

The annals of Chivalry abound with stories of cruel and cold fair ones, who subjected their lovers to extremes of danger, in hopes that they might get rid of their addresses, but were, upon their unexpected success, caught in their own snare, and, as ladies who would not have their name made the theme of reproach by every minstrel, were compelled to recompense the deeds which their champion had achieved in their name.  There are instances in which the lover used his right of reprisals with some rigour, as in the well-known fabliau of the three knights and the shift; in which a lady proposes to her three lovers, successively, the task of entering, unarmed, into the mêlée of a tournament, arrayed only in one of her shift. The perilous proposal is declined by two of the knights and accepted by the third, who thrusts himself, in the unprotected state required, into all the hazards of the tournament, sustains many wounds, and carries off the prize of the day.

There are instances in which the lover used his right of reprisals with some rigour, as in the well-known fabliau of the three knights and the shift; in which a lady proposes to her three lovers, successively, the task of entering, unarmed, into the mêlée of a tournament, arrayed only in one of her shift. The perilous proposal is declined by two of the knights and accepted by the third, who thrusts himself, in the unprotected state required, into all the hazards of the tournament, sustains many wounds, and carries off the prize of the day.

On the next day the husband of the lady (for she was married) was to give a superb banquet to the knights and nobles who had attended the tourney. The wounded victor sends the shift back to its owner, with his request, that she would wear it over her rich dress on this solemn occasion, soiled and torn as it was, and stained all over with the blood of its late wearer. The lady did not hesitate to comply, declaring, that she regarded this shift, stained with the blood of her “fair friend, as more precious than if it were of the most costly materials.” Jaques de Basin, the minstrel who relates this curious tale, is at a loss to say whether the palm of true love should be given to the knight or to the lady on this remarkable occasion. The husband, he assures us, had the good sense to seem to perceive nothing uncommon in the singular vestment with which his lady was attired, and the rest of the good company highly admired her courageous requital of the knight’s gallantry. It was the especial pride of each distinguished champion, to maintain, against all others, the superior worth, beauty, and accomplishments of his lady; to bear her picture from court to court, and support, with lance and sword, her superiority to all other dames, abroad or at home. To break a spear for the love of their ladies, was a challenge courteously given, and gently accepted, among all true followers of Chivalry, and history and romance are alike filled with the tilts and tournaments which took place upon this argument, which was ever ready and ever acceptable. Indeed, whatever the subject of the tournament had been, the lists were never closed until a solemn course had been made in honour of the ladies.

There were knights yet more adventurous, who sought to distinguish themselves by singular and uncommon feats of arms in honour of their mistresses; and such was usually the cause of the whimsical and extravagant vows of arms which we have subsequently to notice. To combat against extravagant odds, to fight amid the press of armed knights without some essential part of their armour, to do some deed of audacious valour in face of friend and foe, were the services by which the knights strove to recommend themselves, or which their mistresses (very justly so called) imposed on them as proofs of their affection.

Sometimes the patience of the lover was worn out by the cold-hearted vanity which thrust him on such perilous enterprises. At the court of one of the German emperors, while some ladies and gallants of the court were looking into a den where two lions were confined, one of them purposely let her glove fall within the palisade which enclosed the animals, and commanded her lover, as a true knight, to fetch it out to her. He did not hesitate to obey, jumped over the enclosure ; threw his mantle towards the animals as they sprung at him; snatched up the glove, and regained the outside of the palisade. But when in safety, he proclaimed aloud, that what he had achieved was done for the sake of his own reputation, and not for that of a false lady, who could, for her sport and cold-blooded vanity, force a brave man on a duel so desperate. And, with the applause of all that were present, renounced her love for ever. This, however, was an uncommon circumstance. In general, the lady was supposed to have her lover’s character as much at heart as her own, and to mean by pushing him upon enterprises of hazard give him an opportunity of meriting her good graces, which she could not with honour confer upon one undistinguished by deeds of chivalry.

Sometimes the patience of the lover was worn out by the cold-hearted vanity which thrust him on such perilous enterprises. At the court of one of the German emperors, while some ladies and gallants of the court were looking into a den where two lions were confined, one of them purposely let her glove fall within the palisade which enclosed the animals, and commanded her lover, as a true knight, to fetch it out to her. He did not hesitate to obey, jumped over the enclosure ; threw his mantle towards the animals as they sprung at him; snatched up the glove, and regained the outside of the palisade. But when in safety, he proclaimed aloud, that what he had achieved was done for the sake of his own reputation, and not for that of a false lady, who could, for her sport and cold-blooded vanity, force a brave man on a duel so desperate. And, with the applause of all that were present, renounced her love for ever. This, however, was an uncommon circumstance. In general, the lady was supposed to have her lover’s character as much at heart as her own, and to mean by pushing him upon enterprises of hazard give him an opportunity of meriting her good graces, which she could not with honour confer upon one undistinguished by deeds of chivalry.

Source:Essays on Chivalry, Romance, and the Drama, by Sir Walter Scott

Chivalry for love (1774)

The following excerpts are from chapter one of ‘On The Origin of Romantic Fiction in Europe‘ (1774). – PW

________________________

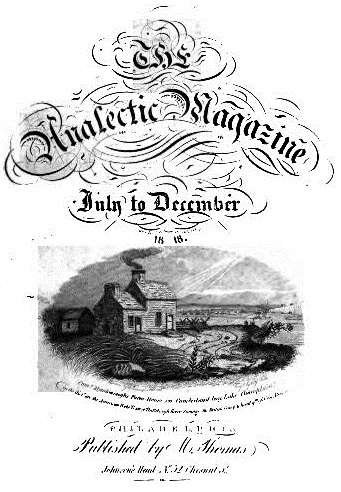

The evolution of chivalry (1818)

The following account on the influence of women on manners and literature in Europe is taken from a review in The Analectic Magazine – vol XII published in Philadelphia in the year 1818.

To read the rest of this 25 page article click here and begin on page 311.

Christine de Pizan: the first gender warrior

By Diana Davison

A long time ago (15th century) in a land not too far away (France) a protofeminist named Christine de Pizan initiated a public debate later named La Querelle de la Rose. Simone de Beauvoir honours Pizan as the first woman to “take up her pen in defence of her sex”[1] but Christine was not fighting for new rights, she was strictly defending the chivalry-based gynocentric culture that she saw crumbling away before her eyes.

Though some feminists deny Christine’s status as a member of the gang, she did seem to have set the standard for how women change the public narrative; lies, elitism, deception and manipulation of history bordering on fraud.

Like all feminists who followed in her footprints, she set a Machiavellian example. The end justifies the means and, while you re-write “herstory”, make sure to claim you are meek and helpless the whole time.

But let us go back to the start of this adventure. We shall travel to c1275 when a man of some talent took up an incomplete poem called La Roman de La Rose and added a whopping 18,824 additional lines to the original 4,000 to create what would become one of the most widely read works of medieval times. Not only did the second author, Jean de Meun, create a cult following, his work was mimicked by Chaucer and Dante. Overall, a charmingly good chap for literary culture.

For over a hundred years this poem proliferated, was translated, adored, and revered as a work of genius. It outlined the troubles and challenges a youth may face when trying to woo a young lady in the world of chivalry. As in most good stories, the goal was not attained easily.

Presented in a dreamlike setting, our hero is guided by personified attributes such as Reason and Genius who help him to bypass all the lady’s defences and capture her “castle.” The language is considered quite risque for the times.

Around 1401 a gentleman named Jean de Montreuil, who served as secretary in the king’s chancery of France, was convinced to read the poem and wrote a glowing review which circulated about the land. It crossed the path of a woman named Christine de Pizan.

Christine was in a unique position compared to other women of her time. She had been raised in the court where her father, despite her mother’s disapproval, urged her to learn how to read and write. These skills came in handy after both her father and husband died quite young leaving Christine with debt and children. She was not overly pleased with her reduction of social status but managed to secure some work as a copyist instead of having to work at spinning or other demeaning trades.

She had begun by writing romantic poetry and secured some patrons who paid her for the work she sent them. She was a clever mimic and was able to write in whatever style her patrons preferred. She would likely have continued to meet survival needs as things were but decided, upon seeing Montreuil’s treatise, to take a chance and use her pen in defence of her desire to improve her career.

She had begun by writing romantic poetry and secured some patrons who paid her for the work she sent them. She was a clever mimic and was able to write in whatever style her patrons preferred. She would likely have continued to meet survival needs as things were but decided, upon seeing Montreuil’s treatise, to take a chance and use her pen in defence of her desire to improve her career.

Thus began an exchange of letters between Christine and defenders of the poem La Roman de La Rose.

These letters became public because Christine de Pizan decided to publish them. She was quite creative in her publishing by arranging them out of chronological order and removing the best arguments that her opponents had offered. Just like a feminist.

Some of the missing letters have since been recovered.

Christine’s main problem with the famous poem amounts to censorship. She takes exception to the naming of genitals and with advice being given as to how to trick women into having sex. Christine was a very conservative Christian. As such, you might think that she really did find the whole storyline repulsive if she hadn’t stated in a letter that the debate was “good-humored, an example of a difference of opinion between worthy persons”[2] and mentioned in another letter that a reply made her laugh.

The Romance of the Rose is rather bawdy and, at times, obscene: kind of like The Vagina Monologues.

Christine intitiated the debate by replying to a letter she acknowledged was not addressed to her. She bypassed that fact by publishing the letters out of order to make her “reply” look solicited.

She begins by stating that her opponents are very learned and that she is very ignorant, which she hopes will not taint their reading of her correspondence. She claims to be weak and timid. Of course, only timid people publish private letters and send copies of it to the Queen.

She begins by stating that her opponents are very learned and that she is very ignorant, which she hopes will not taint their reading of her correspondence. She claims to be weak and timid. Of course, only timid people publish private letters and send copies of it to the Queen.

Speaking of the Queen, who was one of Christine’s patrons, one of Pizan’s approaches was to link female virtue directly to Queen Isabeau of Bavaria “to the point at which the Queen becomes synonymous with virtue, Christine essentially lays the Queen under an obligation to accept her position; not to do so would be to reject her very self.”[3]

Nice trick.

Despite feminist claims that Christine tackled this monumental task alone, she was abetted by Jean Gerson, a long time family friend from her courtly days. Gerson was a strange bedfellow but he and Christine shared some religious ideals and were united both on the misogyny front and in speaking out about the “body politic” in other works. He’s not always mentioned in the discussions of the Querelle because feminists would like you to think Christine didn’t have a white knight helping her out.

The problem faced by both Pizan and Gerson was that de Meun’s poem was, and is, a work of art. When his characters speak they speak as that character would and do not represent the thinking of either the author or God. That is often the problem of censorship fanatics. The other big problem is that they have to admit they actually read the cursed thing.

When you read something distasteful, it is hard to blame anyone but yourself for the fact that you read it. If you didn’t read it or look at it, you can hardly have an opinion. Christine claims to have skim read over the worst of the worst but still approaches it as if she can fully assess the artistic merits of the work.

The accusations against her, which she deletes from her version of events, are that she is a novice who can’t comprehend advanced works and that she is speaking out of turn because she got a lot of recent praise and is suddenly full of her own ego:

“Yet what do we make of Pierre Col’s contention, suppressed by Christine, that her actions have resulted from her envy of ‘la tres elevee haultesse du liver’ [the very loftiness of the book], and that she had better be careful so as not to suffer the fate of the crow who, when ‘someone praised his song, began to sing louder than usual and let his mouthful fall.'”[4]

Christine responds with continued claims to humility and simplicity which, ironically and with calculation, guarantee her fame.

While feminists praise Pizan as a defender of women, only a third of what she wrote in the debate is devoted to perceptions of women. The majority of her complaint is pure Christian objection to obscenity.[5] The purpose of her diatribe can be discerned in the writings that followed, after winning the prestige to write full fledged books.

So what did she write next?

The iconic work in the list of some feminist “must read” resources is Christine de Pizan’s City of Ladies. This is the first book that she published after the Querelle which took up the cause of women.

The City of Ladies copies the format of previous male writers, like de Muen, who present a story in allegorical dream sequence. As a character in her own book Pizan is ordered by her ficitonal ladies of Reason, Rectitude, and Justice, to construct an city with her pen in which women can take shelter. Not all women, only “virtuous” women of her discernment. Christine doesn’t actually believe that all women are good and pure and worthy of men’s love, she just wants to build really solid walls behind which some women can hide so that they can continue to be treated as godly creatures while the other women burn in fucking hell. It was a form of alchemy: Burn off the undesirables.

“Only ladies who are of good reputation and worthy of praise will be admitted into this city. To those lacking in virtue, its gates will remain forever closed” [6]

Those whores are giving women a bad name. Slut-shaming Central.

The gates of Pizan’s City are locked tight to adulteresses, lustful women of any sort, and those who don’t uphold Christine’s religious ideals. She has built this city on the foundations of mythical women, appointed the Virgin Mary as queen (who she alludes to herself as representing), and predicts that her city of imaginary wonder will never fall. It can’t because it’s not real.

The gates of Pizan’s City are locked tight to adulteresses, lustful women of any sort, and those who don’t uphold Christine’s religious ideals. She has built this city on the foundations of mythical women, appointed the Virgin Mary as queen (who she alludes to herself as representing), and predicts that her city of imaginary wonder will never fall. It can’t because it’s not real.

If we had any doubt about Christine’s intentional trickery, we need look no further than the pages of this debut novel which, unlike the letters of the Querelle, are unmolested. She takes examples of awesome women from the Bible and pagan mythologies and leaves out all the bad parts of the stories so that they all look virtuous.

For example, Abraham’s wife, Sarah, becomes a woman who was so lusted after that King Pharaoh forcibly stole her from her husband. For those who actually read the bible, you’ll find out that Sarah and Abraham tricked Pharaoh by telling him they were siblings so that he might fall in love and give her many riches. When God punished Pharaoh for seducing a married woman Pharaoh was flabbergasted and gave them whatever they wanted just to get the fuck out of town. They pulled this trick twice. And it turns out they actually were brother and sister. God didn’t seem to care about that.

Christine laments that one of her heroines, Semaramis, married her son to avoid having to share her kingdom with another woman but excuses her because it wasn’t a law at the time that she shouldn’t do that. That Semaramis managed to defend her kingdom after the death of her husband was more important than the laws of nature. The laws of nature are somewhat mutable in Christine’s world, when it suits her purpose.

“As for those men who are slanderous by nature, it’s not surprising if they criticize women, given that they attack everyone indiscriminately. You can take it from me that any man who wilfully slanders the female sex does so because he has an evil mind, since he’s going against both reason and nature.” [7]

So it’s in man’s nature to go against nature? It’s not hard to argue against logic like that.

In the final reading, we are left to wonder what it is Christine was really trying to accomplish. Did she think women were strong, capable people or objects to be fawned over and worshipped like children or gods? Christine answers that upon seeing the perfect dream ladies of her vision who arrive to show her the path of truth:

“I didn’t know which of my senses was the more struck by what she said: whether it was my ears as I took in her stirring words, or my eyes as I admired her great beauty and dress, her noble bearing and face.” [8]

Christine! You misogynist!!

How dare you objectify these women with your gaze?

Christine’s “city” presents and shelters women as goddesses. Like Pygmalion, who was uninterested in real women, she sculpts the perfect female so that men can worship the illusion. Christine was a traditionalist attempting to uphold and entrench all the privileges enjoyed by her gender since chivalric love had been introduced.

As a pioneer of feminism, she taught those who followed that every female flaw which can’t be excused can be erased from herstory.

Sources:

1. Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, p105

2. Heather Bamford, Remember the giver(s): the creation of the Querelle and notions of sender and recipient in University of California, Berkeley, MS 109, 2009

3. ibid

4. David F. Hult, Words and Deeds: Jean de Meun’s “Romance of the Rose” and the Hermeneutics of Censorship, New Literary History, Vo. 28, No. 2, Medieval Studies (Spring, 1997)

5. Ibid

6. Christine de Pizan, City of Ladies, p11

7. ibid, p19-20

8. ibid, p9

Editor’s note: feature image by Hans Splinter. –PW

The Art of Courtly Love

The Art of Courtly Love (Twelfth Century)

The Art of Courtly Love was written by Andreas Capellanus in 1190. The volume falls into three large units or “books.” Book One, “Introduction to the Treatise on Love,” defines love as “a certain inborn suffering derived from the sight of and excessive meditation upon the beauty of the opposite sex, which causes each one to wish above all things the embraces of the other.” There is no question that love is suffering, says Andreas, because “before the love becomes equally balanced on both sides there is no torment greater, since the lover is always in fear that his love may not gain its desire.”

True love is an ennobling experience, for it can endow a man with nobility of character, can cause a proud man to be humble, and can cause a selfish man to perform many graceful services:

O what a wonderful thing is love, which makes a man shine with so many virtues and teaches everyone, no matter who he is, so many good traits of character! . . . It adorns a man, so to speak, with the virtue of chastity, because he who shines with the light of one love can hardly think of embracing another woman, even a beautiful one. For when he thinks deeply of his beloved the sight of any other woman seems to his mind rough and rude.

Much of Book One is a series of dialogues showing how a man of one class might speak of his love with a woman of his own or another class. Here are excerpts from the “seventh dialogue,” one in which a man of the higher nobility speaks with a woman of the simple nobility. He has not before met the woman, but he has heard her praised by others:

THE MAN SAYS: I ought to give God greater thanks than any other living man in the whole world because it is now granted me to see with my eyes what my soul has desired above all else to see. . . . And I now know in very truth that a human tongue is not able to tell the tale of your beauty and your prudence. . . . And I wish ever to dedicate to your praise all the good deeds that I do and to serve your reputation in every way. For whatever good I may do, you may know that it is done with you in mind. . . .

THE WOMAN SAYS: I am bound to give you many thanks for lauding me with such commendations and exalting me with such high praise . . . I am therefore glad if I am to you a cause and origin of good deeds, and so far as I am able I shall always and in all things give you my approval when you do well. . . .

THE MAN SAYS: I have chosen you from among all women to be my mighty lady, to whose services I wish ever to devote myself and to whose credit I wish to set down all my good deeds. From the bottom of my heart I ask you mercy, that you may look upon me as your particular man, just as I have devoted myself particularly to serve you, and that my deeds may obtain from you the reward I desire. . . .

THE WOMAN SAYS: Your request that I should consider you as my particular man, just as you are particularly devoted to my service, and that I should give you the reward you hope for, I do not see how I can grant, since such partiality might be to the disadvantage of others who have as much desire to serve me as you have, or perhaps even more. Besides I am not perfectly clear as to what the reward is that you expect from me; you must explain yourself more clearly. . . .

THE MAN SAYS: The reward I ask you to promise to give me is one which it is unbearable agony to be without, while to have it is to abound in all riches. It is that you should be pleasant to me unless your desire is opposed to me. It is your love which I seek, in order to restore my health.. . .

THE WOMAN SAYS: You seem to be wandering a long way from the straight path of love and to be violating the best custom of lovers, because you are in such haste to ask for love. For the wise and well-taught lover, when conversing for the first time with a lady whom he has not previously known, should not ask in specific words for the gifts of love. We are separated by too wide and too rough an expanse of country to be able to offer each other love’s solaces or to find proper opportunities for meeting. Lovers who live near together can cure each other of the torments that come from love. . . . Therefore everybody should try to find a lover who lives near by.

The woman argues that love really can exist between husband and wife. Neither she nor he will yield on this crucial point, and in the end they submit the matter to the Countess of Champagne and agree to abide by her ruling on this question. She replies to the woman’s letter in one dated May 1, 1174: “We declare and we hold as firmly established that love cannot exert its powers between two people who are married to each other. For lovers give each other everything freely, under no compulsion of necessity, but married people are in duty bound to give in to each other’s desires and deny themselves to each other in nothing.”

Here are excerpts from the “eighth dialogue,” one in which a man and woman both of the higher nobility enter into a dialogue. Andreas states that if a man of higher nobility should seek the love of a woman of the same class, he should first above all things follow the rule to use soft and gentle words, and he should take care not to say anything that would seem to deserve reproof. For a noblewoman or a woman of higher nobility is found to be very ready and bold in censuring the deeds or the words of a man of the higher nobility, and she is very glad if she has a good opportunity to say something to ridicule him.

THE MAN SAYS: Indeed it is true that god has inclined all good men in this life to serve your desires and those of other ladies, and it seems to me that this is for the very clear reason that men cannot amount to anything nor taste of the fountain of goodness unless they do this under the persuasion of ladies… It is clear that every man should strive with all his might to be of service to ladies so that he may shine by their grace. But ladies are greatly obligated to keeping the hearts of good men set upon doing good deeds and to honor every man according to his deserts. For whatever good things living men may say or do, they generally credit them all to to the praise of women, and by serving women they so act that they may pride themselves on the rewards they receive from them, and without these rewards no man can be of use in this life or be considered worthy of any praise. Now I know many men who are sure they have been given perfect love, and I know others who are maintained only by the milk of nourishing hope; but I, who have neither perfect love nor the gift of hope, am more sustained merely by the pure thought of you, which I do have, than all other lovers are by unnumbered solaces. May your pity therefore turn and regard my solitary thought and give it a little increase. And truly I beg you must earnestly not try to keep away from Love’s court, for those who stay away from the palace of Love live for themselves alone, and no one gets any profit from their lives…

THE WOMAN SAYS: Although your words are deep and profound and reach to the walls of Love’s subtlety, I shall try, as far as I am able, to give them a fitting answer. And because the experience of Cicero tells us that the things which are said last in a discourse are more readily retained in the memory, I shall try to answer your last remarks first. Now your urging me to strive to do what might increase my good character and that of others was pleasing and acceptable enough to me, because I had it in my heart to do that without advice from anyone. And I know women should, as you have asserted, be the cause and origin of good things… and should persuade every man to do courteous deeds and to avoid everything that has the appearance of boorishness and not to be so tenacious of his own property as to blacken his good name. But to show love is to gravely offend God and to prepare for many the perils of death. And besides it seems to bring innumerable pains to the lovers themselves and to cause them constant torments every day… I myself have had no experience in love and so naturally I can tell you nothing about its nature except so far as I have learned about it from what others tell me.

THE MAN SAYS: It is the pure love which binds together the hearts of two lovers with feelings of delight. This kind consists in the contemplation of the mind and the affection of the heart; it goes as far as the kiss and the embrace and the modest contact with the nude lover, omitting the final solace. . . . But that is called mixed love which gets its effect from every delight of the flesh and culminates in the final act of Venus. . . . This kind quickly fails, and one often regrets having practiced it; by it one’s neighbor is injured, the Heavenly King is offended, and from it come very grave dangers. But I do not say this as though I meant to condemn mixed love, I merely wish to show which of the two is preferable. But mixed love, too, is real love, and it is praiseworthy, and we say that it is the source of all good things, although from it grave dangers threaten, too. Therefore I approve of both pure love and mixed love, but I prefer to practice pure love. . . .

THE WOMAN SAYS: Since a certain woman of the most excellent character wished to reject one of her two suitors by letting him make his own choice, and to accept the other, she divided the solaces of love in her in this fashion. She said, “Let one of you choose the upper half of me, and let the other suitor have the lower half.” Without a moment’s delay each of them chose his part, and each insisted that he had chosen the better part. . . . I ask you which seems to you to have made the more praiseworthy choice.

THE MAN SAYS: Who doubts that the man who chooses the solaces of the upper part should be preferred to the one who seeks the lower? For so far as the solaces of the lower part go, we are in no wise differentiated from brute beasts; but in this respect nature joins us to them. But the solaces of the upper part are, so to speak, attributes peculiar to the nature of man and are by this same nature denied to all the other animals. Therefore the unworthy man who chooses the lower part should be driven out from love just as though he were a dog, and he who chooses the upper part should be accepted as one who honors nature. Besides this, no man has ever been found who was tired of the solaces of the upper part, or satiated by practicing them, but the delight of the lower part quickly palls upon those who practice it, and it makes them repent of what they have done.

From Book II of The Art of Courtly Love, entitled “How Love May be Retained,” I shall quote only a few of the 31 “rules of love which the King of Love himself, with his own mouth, pronounced for lovers”:

1. Marriage is no real excuse for not loving.

2. He who is not jealous cannot love.

10. Love is always a stranger in the home of avarice.

11. It is not proper to love any woman whom one should be ashamed to seek to marry.

13. When made public, love rarely endures.

14. The easy attainment of love makes it of little value; difficulty of attainment makes it prized.

15. Every lover regularly turns pale in the presence of his beloved.

16. When a lover suddenly catches sight of his beloved his heart palpitates.

17. A new love puts to flight an old one.

19. If love diminishes, it quickly fails and rarely revives.

20. A man in love is always apprehensive.

21. Real jealousy always increases the feeling of love.

22. Jealousy, and therefore love, are increased when one suspects his beloved.

23. He whom the thought of love vexes, eats and sleeps very little.

27. A lover can never have enough of the solaces of his beloved.

28. A slight presumption causes a lover to suspect his beloved.

29. A true lover is constantly and without intermission possessed by the thought of his beloved.

Primary source: Andreas Capellanus, The Art of Courtly Love, translated by John Jay Parry (New York, Columbia University Press, 1941). [FULL TEXT]

Some introductory remarks above by Peter G. Beidler, – from Backgrounds to Chaucer,

C.S. Lewis on courtly love

The following is an excerpt of C.S. Lewis’ book The Allegory of Love: A Study of the Medieval Tradition, which can be purchaced from Amazon

Andreas Capellanus (1174) on ‘women’s nature’

Middle Ages Europe is widely considered the birthplace of ‘protofeminism’ – the forerunner to modern feminism. At that time a chaplain named Andreas Capellanus, whom we might consider the first antifeminist and ‘MGTOW’ of the period, wrote a book describing the escalating problem of female avarice, manipulativeness, narcissism, underserved sense of entitlement, and hypergamy. Interestingly, Andreas links all these problems with the birth of courtly love – the subject of his book – and recommends all men learn to reject romantic relationships with women and “trample under your foot all of its rules.”

While the piece is written in anger at the emerging gynocentric culture, it contains truths that echo much of what MGTOW are reacting to today – in particular the world’s encouragement, protection and enforcement of female hypergamy. The following is an excerpt from Capellanus’ amazing work. PW

THE ART OF COURTLY LOVE

By Andreas Capellanus (1174)

The mutual love which you seek in women you cannot find, for no woman ever loved a man or could bind herself to a lover in the mutual bonds of love. For a woman’s desire is to get rich through love, but not to give her lover the solaces that please him. Nobody ought to wonder at this, because it is natural. According to the nature of their sex all women are spotted with the vice of a grasping and avaricious disposition, and they are always alert and devoted to the search for money or profit. I have travelled through a great many parts of the world, and although I made careful inquiries I could never find a man who would say that he had discovered a woman who, if a thing was not offered to her, would not demand it insistently and would not hold off from falling in love unless she got rich gifts in one way or another. But even though you have given a woman innumerable presents, if she discovers that you are less attentive about giving her things than you used to be, or if she learns that you have lost your money, she will treat like a perfect stranger who has come from some other country, and everything you do will bore her or annoy her. You cannot find a woman who will love you so much or be so constant to you that if somebody else comes to her and offers her presents she will be faithful to her love.

The mutual love which you seek in women you cannot find, for no woman ever loved a man or could bind herself to a lover in the mutual bonds of love. For a woman’s desire is to get rich through love, but not to give her lover the solaces that please him. Nobody ought to wonder at this, because it is natural. According to the nature of their sex all women are spotted with the vice of a grasping and avaricious disposition, and they are always alert and devoted to the search for money or profit. I have travelled through a great many parts of the world, and although I made careful inquiries I could never find a man who would say that he had discovered a woman who, if a thing was not offered to her, would not demand it insistently and would not hold off from falling in love unless she got rich gifts in one way or another. But even though you have given a woman innumerable presents, if she discovers that you are less attentive about giving her things than you used to be, or if she learns that you have lost your money, she will treat like a perfect stranger who has come from some other country, and everything you do will bore her or annoy her. You cannot find a woman who will love you so much or be so constant to you that if somebody else comes to her and offers her presents she will be faithful to her love.

Women have so much avarice that generous gifts break down all the barriers of their virtue. If you come with open hands, no women will let you go away without that which you seek; while if you don’t promise to give them a great deal, you needn’t come to them and ask for anything. Even if you are distinguished by royal honors, but bring no gifts with you, you will get absolutely nothing from them; you will be turned away from their doors in shame. Because of their avarice all women are thieves, and we say they carry purses. You cannot find a woman of such lofty station or blessed with such honor or wealth that an offer of money will not break down her virtue, and there is no man, no matter how disgraced and low-born he is, who cannot seduce her if he has great wealth. This is so because no woman ever has enough money – just as no drunkard ever thinks he has had enough to drink. Even if the whole earth and sea were turned to gold, they could hardly satisfy that avarice of a woman.

Furthermore, not only is every woman by nature a miser, but she is also envious and a slanderer of other women, greedy, a slave to her belly, inconstant, fickle in her speech, disobedient and impatient of restraint, spotted with the sin of pride and desirous of vainglory, a liar, a drunkard, a babbler, no keeper of secrets, too much given to wantonness, prone to every evil, and never loving any man in her heart.

Now woman is a miser, because there isn’t a wickedness in the world that men can think of that she will not boldly indulge in for the sake of money, and, even if she has an abundance she will not help anyone who is in need. You can more easily scratch a diamond with your fingernail than you can by any human ingenuity get a woman to consent to giving you any of her savings. Just as Epicurus believed that the highest good lay in serving the belly, so a woman thinks that the only things worth while in this world are riches and holding on to what she has. You can’t find any woman so simple and foolish that she is unable to look out for her own property with a greedy tenacity, and with great mental subtlety get hold of the possessions of someone else. Indeed, even a simple woman is more careful about selling a single hen than the wisest lawyer is in deeding away a great castle. Furthermore, no woman is ever so violently in love with a man that she will not devote all her efforts to using up his property. You will find that this rule never fails and admits of no exceptions.

That every woman is envious is also found to be a general rule, because a woman is always consumed with jealousy over another woman’s beauty, and she loses all her pleasure in what she has. Even if she knows that it is the beauty of her own daughter that is being praised, she can hardly avoid being tortured by hidden envy. Even the neediness and the great poverty of the neighbour women seem to her abundant in wealth and riches, so that we think of the old proverb which says, “the crop in the neighbour’s field is always more fertile, and your neighbour’s cow has a larger udder,” seems to refer to the female sex without question. It can hardly come to pass that one woman will praise the good character or the beauty of another, and if she should happen to do so, the next minute she adds some qualification that undoes all she has said in her praise.

And so it follows that woman is a slanderer, because slander can only spring from envy and hate. That is a rule that women do not want to break; she prefers to keep it unbroken. It is not easy to find a woman whose tongue can ever spare anybody or who can keep from words of detraction. Every woman thinks that by running down others she adds to her own praise and increases her own reputation – a fact which shows very clearly to everybody that women have very little sense. For all men agree to hold it as a general rule that words of dispraise only hurt the person who utters them, and they detract from the esteem in which he is held; but no woman on this account keeps from speaking evil and attacking the reputation of good people, and so I think we can insist that no woman is really wise. Qualities that a wise man has are wholly foreign to a woman, because she believes, without thinking, everything she hears, and she is very free about insisting on being praised, and she does a great many other unwise things which it would be tedious for me to enumerate.

…

The feminine sex is also commonly tainted by arrogance, for a woman, when incited by that, cannot keep her keep her tongue or her hands from crimes or abuse, but in her anger she commits all sorts of outrages. Moreover, if anybody tries to restrain an angry woman, he will tire himself out with a vain labor, for you cannot keep her from her evil designs or soften her arrogance of soul. Any woman is incited to wrath by a mild enough remark of little significance and indeed at times by nothing at all; and her arrogance grows to tremendous proportions; and as far as I can recall no one ever saw a woman who could restrain it.

Furthermore every woman seems to despise all other women – a thing which we know comes from pride. No person could despise another unless he looked down upon him because of pride. Besides, every woman, not only a young one but even the old and decrepit, strives with all her might to exalt her own beauty; this can come only from pride, as the wise man said very clearly when he said, “There is arrogance in everybody and pride follows beauty.” Therefore it is perfectly clear that women can never have perfectly good characters, because, as they say, “A remarkable character is soiled by an admixture of pride.”

Every woman is also loud-mouthed, since no one of them can keep her tongue from abuses, and even if she loses a single egg she will keep up a clamor all day like a barking dog, and she will disturb the whole neighbourhood over a trifle. When she is with other women, no one of them will give the others a chance to speak, but each always tries to be the one to say whatever is to be said and to keep on talking longer than the rest; and neither her tongue nor her spirit ever gets tired of talking. A woman will boldly contradict everything you say, and she can never agree with anything, but she always tries to give her opinion on every subject.

No woman is attached to her lover or bound to her husband with such pure devotion that she will not accept another lover, especially if a rich one comes along, which shows the wantonness as well as the great avarice of a woman. There isn’t a woman in this world so constant and so bound by pledges that, if a lover of pleasures comes along and with skill and persistence invites her to the joys of love, she will reject his entreaties – at any rate if he does a good deal of urging. No woman is an exception to this rule either. So you can see what we ought to think of a woman who is in fortunate circumstances and is blessed with an honourable lover or the finest of husbands, and yet lusts after some other man. But that is precisely what women do who are too much troubled with wantonness.

Indeed, a woman does not love a man with her whole heart, because there is not one of them who keeps faith with her husband or her lover; when another man comes along, you will find that her faithfulness wavers. For a woman cannot refuse gold or silver or any other gifts that are offered her, nor can she on that account deny the solaces of her body when they are asked for. But since the woman knows that nothing so distresses her lover as to have her grant these to some other man, you can see how much affection she has for a man when, out of greed for gold or silver, she will give herself to a stranger or a foreigner and has no shame about upsetting her lover so completely and shattering the jewel of her own good faith. Moreover, no woman has such strong bond of affection for a lover that if he ceases to woo her with presents she will not become luke-warm about her customary solaces and quickly become like a stranger to him.

Avoid love and trample under foot all of its rules:

It doesn’t seem proper, therefore, for any prudent man to fall in love with any woman, because she never keeps faith with any man. Everybody knows that she ought to be spurned for the innumerable weighty reasons already given. Therefore it is not advisable, my respected friend, for you to waste your days on love, which for all the reasons already given we agree ought to be condemned. For if it deprives you of the grace of the Heavenly King, and costs you every real friend, and it takes away all the honors of this world as well as every breath of praiseworthy reputation, and greedily swallows up all your wealth, and is followed by every sort of evil. As has already been said, why should you, like a fool, seek for love, or what good can you get from it that will repay you for all these disadvantages? That which above all you seek in love – the joy of having your love returned – you can never obtain, as we have already shown, no matter how hard you try, because no woman ever returns a man’s love. Therefore if you will examine carefully all the things that go to make up love, you will see clearly that there are conclusive reasons why a man is bound to avoid it with all his might and to trample under foot all its rules.

If you will study carefully this little treatise of ours and understand it completely and practice what it teaches, you will see clearly that no man ought to mis-spend his days in the pleasures of love. If you abstain from it, the Heavenly King will be more favorably disposed toward you in every respect, and you will be worthy to have all prosperous success in this world and to fulfill all praiseworthy deeds and the honorable desires of your heart, and in the world to come to have glory and life everlasting.

Source

The Art of Courtly Love, by Andreas Capellanus, written in 1174, Translated by John Parry in 1941; Excerpt is from pp. 200-211

? The image above shows a golden casket from the Middle Ages depicting scenes of servile male behaviour typical of the emerging culture of courtly love. Such objects were given to women as gifts by men seeking to impress. (Note the woman standing with hands on hips in a position of authority, and the man in blue being led around by a yoke or leash in a position of subservience).

Freedom from gynocentrism in 12 Steps

Written by August Løvenskiolds

Are you sick of seeing good men destroyed? Tired of being assaulted by women? Sick at craziness and brutality being tolerated when they come from women but swiftly punished when a man even hints at them? Worried at the prospect of your young children being taken from you, and turned against you, by a woman who wants to rape your wallet?

Disgusted at the thought of showing chivalry and deference to foul-mouthed, thieving, drunken, sloppy and disrespectful harlots[1]? Enraged at the thought that newborn baby boys are sexually mutilated in order to tart up ladies’ cosmetics?

These are but a few of the many paths that might’ve brought you to this red door, and many wounds and diseases can be treated with the red pill, but your recovery will take conscious effort and patience on all of our parts – I know, because mine sure did, and I still struggle with it every day.

An AVfM Commenter suggested recently that a 12 Step program for recovering feminists might be necessary. I’ve been kicking around a similar idea for a while now, but my version is for any blue or purple pill person interested in taking the red pill.

What are the red, blue, and purple pills? They are metaphors for your worldview. I’ll be using a lot of MHRM buzzwords in this article, and part of your recovery will center around your taking responsibility for researching them for yourself.

Now, 12 Step Programs have been around for a while (I even helped found one back in the mid 1980’s) and have mixed records of success, but since they are well-known they can serve as a helpful framework to map out what you can expect once you start breaking the chains of gynocentrism. So, stealing shamelessly from those who have blazed the trail, I give you an overview of:

The 12 Steps of Liberation from Gynocentrism

Step 1: Honesty

After many years of denial, recovery can begin with one simple realization – that whether from feminism or traditionalism, Gynocentrism means more than equal rights: it is about securing unearned and undeserved comforts, security, money and power for women and women alone, at the expense and often destruction of men, their lives, and their families.

Step 2: Faith in oneself

It seems to be a spiritual truth that before we can break the chains of the expectations that gynocentrism places on men, we must accept that men are worthy creatures undeserving of the shame, self-loathing and lies that are told about us. Men, and the happiness of men, matter. They are critical to the survival of both humankind and human civilization. When enough men give up on it, society dies.

Step 3: Self-liberation

A lifetime of deference to the whims of whining women will come to a screeching halt, and change forever, by making a simple decision to turn it all over to a higher power – one’s own good judgment that men’s needs matter, too. The only true liberation is self-liberation – a slave forced into freedom by others will remain enslaved until he embraces his freedom as his own.

Step 4: Soul-searching

Change is a process, not just an event. Recognizing how our previous attachment to gynocentrism damaged ourselves, the men around us, and yes, the women, too, requires a lot of thought into often unpleasant memories and past experiences. This soul-searching, though painful, will build our strengths and understandings for when we face future conflicts with those still committed to pedestalizing women.

Step 5: Commitment to Personal Integrity and Truth

A most difficult step to face, but also the one that provides the great opportunity for growth. When you commit to personal integrity and truth you will find the courage to face down your fears and stand up for the rights of men where no one else seems willing to make the first objection to male disposability.

Step 6: Acceptance of our Defects

Everyone has personal character faults but such faults are no reason for us to accept unjust treatment. A man with flaws can still be a good father, a hard worker, and a worthy person. No one has the right to shame us for our sexual desires, the choices or flaws in our physical appearance, our accomplishments, our failures, or our infirmities.

Step 7: Confidence and Humility

As we discover and embrace the newfound power that comes with liberation from gynocentrism, we must be cognizant of the need to balance our confidence with humility – not the false humility from shame, but rather, a knowledge that our strength has real limits and that personal growth can be a frustrating process at times. We must learn to be confident enough in our worth and skills that we can accept new challenges – challenges we are humble enough to understand that we might fail at achieving.

Step 8: Willingness to make amends

Making a list of those we harmed before coming into recovery from gynocentrism can be daunting – long-term feminists in particular may find they have numerous abortions, falsely accused boyfriends, amputated foreskins and penises, stolen job opportunities, and massive shoe collections hanging over their newly heightened consciences. Becoming willing to actually start the struggle to make amends to those we have wronged can be the most difficult part of recovery and many falter on this step.

Step 9: Forgiveness

Being willing to forgive others as well as asking for forgiveness for ourselves may seem like a bitter red pill to swallow, but for those serious about recovery it can be great medicine for the spirit and soul. Even the failure of gynocentrists to embrace forgiveness will help us in that it will throw their sociopathy into sharper relief.

Step 10: Maintenance

Nobody likes to dwell on past wrongs but continuing study into men’s human rights issues is necessary to maintain progress and vigilance in recovery from gynocentrism, lest we fall back into old habits and long-held, toxic beliefs about men.

Step 11: Making Contact

There is value and strength in contacting others in recovery to share our stories and plan our futures, whether as a group or on our own. In recovering from gynocentrism, the insights of one man or woman can and do enrich all our lives. Additionally, building a community of men who recognize the value in each other is a rare and powerful weapon against gynocentrism. Men don’t bond (in general) as quickly or seamlessly as women do, and whenever men build a space for themselves, women try to bully their way in.

Step 12: Service to Humankind

It is not uncommon for those in gynocentrism recovery programs to experience anger over the pain of our long enslavement to the Golden Uterus. Male anger is a good thing – it is how we heal; it is how we grieve; it is the motivation the drives us to help others. Reaching out to others caught in the violent abattoirs of gynocentric privilege can provide the rare gift of saving and enriching men’s lives rather than gratuitously destroying them. Even a lone MGTOW like me can add to the fight by cutting back and resisting the forces that feed gynocentrism’s ever growing need for power, money, and resources.

***

This is not the end but the beginning. I’ve got a lot more to say, but this article in overdue and overlong already. My warmest regards to you all.

Author’s note: although based loosely on (and sometimes in contradiction to) The Twelve Steps of AA, this article is intended as neither a criticism nor endorsement of AA or any other Multi-Step-based program.

[1] Yes, we are aware that the website for the Traditional Woman’s Rights Activists, or, more aptly named, We-Only-Submit-To-The-Men-Who-Obey-Us knitting circle and coffee clutch assembly no longer exists. Thank God and/or the Spaghetti Monster.