Lester F. Ward, an American botanist, paleontologist, sociologist and an early ‘feminist’ thinker, proposed a gynocentric theory that women are superior to men. Aside from this theory, Ward wrote about the origins of romantic love, which is presented below in full. -PW

_____________

All social forces are psychic, and in that sense spiritual. The application to any of them of the term physical, is therefore not strictly correct, but if it is done not to stigmatize them, but for the sake of distinguishing some from others, it may be justified and even useful. All feeling is psychic, but feelings differ in many ways, and among others in a certain greater or less remoteness from their physical seat, or vagueness and indefiniteness with regard to the location of the nerve plexuses, by the molecular activities within which the feelings are occasioned. Another difference consists in the degree in which the feeling is external or internal, and still another is that of the relative intensity and durability of feelings.

All these differences are more or less correlated, and in general those feelings which are most vague and least definitely located in the body, those that are most internal, and those that are least intense and most durable, are classed as more spiritual, more elevated, and more refined. And in fact, there can be no doubt of the general correctness of this popular view, and, as has already been said, the true reason why this latter class of feelings is regarded as superior is that they yield a larger aggregate amount of satisfaction. Though lower from the standpoint of necessity, since they are not essential to life, they are higher from the standpoint of utility, i.e., they are worth more – more worthy.

But these feelings are derivative, and are the consequences of a qualitative development of the physical organization of man. For it is not the brain of man alone that has developed. The brain is only one of the many nerve plexuses of the body, and there is no reason to suppose that it is the only one that has undergone structural refinement. The brain has now been studied and the chief causes of mental superiority have been discovered. Primarily brain mass is the cause of intelligence, and until the process of cephalization had far advanced and the relatively large hemispheres had been superposed upon the original ganglionic nucleus, there could be no advance sufficient to constitute rational beings. And this attained, other things equal, increase of brain mass represents increased intelligence.

But this is far from being the whole. There took place qualitative changes, and brains came to differ in kind as well as in size. Since the period of social assimilation this has undoubtedly been the principal advance that has been made. The cross fertilization of cultures worked directly upon these qualitative characters, rendering the most thoroughly mixed races, like the Greeks and the English, highly intelligent. The physiological or histological cause of this improved brain structure is now known in its general aspects. Brain superiority is measured chiefly, first, by the number of neurons in a cubic millimeter of the brain substance, and second, by the degree of extension and ramification of the plumose panicles that proceed from the summit of these pyramidal cells, and by the character of the axis cylinder at their bases.

Now, while there can be no doubt that this higher brain development vitally influences all the other nerve plexuses of the body, since every conscious feeling must be referred to the brain, it is altogether probable that a process of qualitative improvement has also and at the same time been taking place in the entire nervous system, and especially in the great centers of emotion, and if the serious study of these plexuses could be prosecuted, as has been that of the brain, differences would in all probability be detected capable of being described, as this has been done for the brain. In other words, the development of the human race has not consisted exclusively in brain development, but has been a general advance in all the great centers of spiritual activity.

It is this psycho-physiological progress going on in all races that have undergone repeated and compound social assimilation that has laid the foundation for the appearance in the most advanced races of a derivative form of natural love which is known as romantic love. It is a comparatively modern product, and is not universal among highly assimilated races. In fact, I am convinced that it is practically confined to what is generally understood as the Aryan race, or, at most, to the so-called Europeans, whether actually in Europe or whether in Australia, America, India, or any other part of the globe. Further, it did not appear in a perceptible form even in that ethnic stock until some time during the Middle Ages. Although I have held this opinion much longer, I first expressed it in 1896.1 It is curious that since that time two books have appeared devoted in whole or in part to sustaining this view..2 There is certainly no sign of the derivative sentiment among savages. Monteiro, speaking of the polygamous peoples of Western Africa, says: –

The negro knows not love, affection, or jealousy. … In all the long years I have been in Africa I have never seen a negro manifest the least tenderness for or to a negress. … I have never seen a negro put his arm round a woman’s waist, or give or receive any caress whatever that would indicate the slightest loving regard or affection on either side. They have no words or expressions in their language indicative of affection or love.3

Lichtenstein4 says of the Koossas: “To the feeling of a chaste tender passion, founded on reciprocal esteem, and an union of heart and sentiment, they seem entire strangers.” Eyre reports the same general condition of things among the natives of Australia,5 and it would not be difficult to find statements to the same effect relative to savage and barbaric races in all countries where they have been made the subject of critical study. Certainly all the romances of such races that have been written do but reflect the sentiments of their writers, and are worthless from any scientific point of view. This is probably also the case for stories whose plot is laid in Asia, even in India, and the Chinese and Japanese seem to have none of the romantic ideas of the West; otherwise female virtue would not be a relative term, as it is in those countries. This much will probably be admitted by all who understand what I mean by romantic love.

The point of dispute is therefore apparently narrowed down to the question whether the Ancient Greeks and Romans had developed this sentiment. I would maintain the negative of this question. If I have read my Homer, Æschylus, Virgil, and Horace to any purpose they do not reveal the existence in Ancient Greece and Rome of the sentiment of romantic love. If it be said that they contain the rudiments of it and foreshadow it to some extent I shall not dispute this, but natural love everywhere does this, and that is therefore not the question.

The only place where one finds clear indications of the sentiment is in such books as “Quo Vadis,” which cannot free themselves from such anachronisms. I would therefore adhere to the statement made in 1896, when I said, “Brilliant as were the intellectual achievements of the Greeks and Romans, and refined as were many of their moral and esthetic perceptions, nothing in their literature conclusively proves that love with them meant more than the natural demands of the sexual instinct under the control of strong character and high intelligence. The romantic element of man’s nature had not yet been developed.”

The Greeks, of course, distinguished several kinds of love, and by different words (eros, agape, philia), but only one of these is sexual at all. For eros they often used ‘Aphrodite’. They also expressed certain degrees and qualities in these by adjectives, e.g., pandemic. Some modern writers place the adjective heavenly over against pandemic, as indicating that they recognized a sublimated, heavenly, or spiritual form of sexual love, but I have not found this in classic Greek. Neither do I find any other to the Latin Venus vulgivaga. But whether such softened expressions are really to be found in classic Greek and Latin authors or not, the fact that they are so rare sufficiently indicates that the conceptions they convey could not have been current in the Greek and Roman mind, and must have been confined to a few rare natures.

Romantic love is therefore not only confined to the historic races, those mentioned in Chapter III as representing the accumulated energies of all the past and the highest human achievement, but it is limited to the last nine or ten centuries of the history of those races. It bean to manifest itself some time in the eleventh century of the Christian era, and was closely connected with the origin of chivalry under the feudal system. Guizot has given us perhaps the best presentation of that institution,6 and from this it is easy to see how the conditions favored its development.

In the first place the constant and prolonged absenteeism of the lords and knights, often with most of their retainers, from the castle left the women practically in charge of affairs and conferred upon them a power and dignity never before possessed. In the second place the separation of most of the men for such long periods, coupled with the sense of honor that their knighthood and military career gave rise to, caused them to assume the rôle of applicants for the favor of the women, which they could not always immediately attain as when women were forcibly seized by any one that chanced to find them.

These conditions produced a mutual sense on the part of both sexes of the need of each other, coupled with prolonged deprivation on the part of both of that satisfaction. The men, thus seeking the women, naturally became chivalrous toward them. The solitary life of women of high rank made them somewhat a prey to the lusts of men of low degree, and the knights assumed the rôle of protecting them from all dangers. Moral and Christian sentiments also played a part, and we find among the provisions of the oath that every chevalier must make the following solemn vows: –

To maintain the just rights of the weak, as of widows, orphans, and young women. If called upon to conduct a lady or a girl to any place, to wait upon her, to protect her, and to save her from all danger and every offense, or perish in the attempt. Never to do violence to ladies or young women, even though won by their arms, without their will and consent.

Such an oath, made a universal point of honor, any breach of which would be an everlasting disgrace, and be punished severely by the order of knighthood to which they belonged, could not fail to produce a powerful civilizing effect upon the semi-barbaric men of that age. The whole proceeding must have also given to women a far greater independence and higher standing than they had ever before enjoyed since the days of gynæcocracy in the protosocial stage.

Out of this condition of things there arose a special class of poets who wrote lyrics wholly different from the erotic songs of antiquity that go by that name. These poets were called troubadours, and some of them wandered from place to place singing the praises of the great court ladies, and still further inflaming the new passion, which was relatively pure, and contented itself with an association of men with women while conserving the honor and virtue of the latter. This, of course, was a passing phase and somewhat local, being mainly confined to southern France and parts of Spain.

It degenerated, as did the whole institution of chivalry, and by the end of the thirteenth century nothing was left of either but the ridiculous nonsense that Cervantes found surviving into his time, and which he so happily portrayed in Don Quixote. But chivalry had left its impress upon the world, and while Condorcet and Comte exaggerated certain aspects of it, no one has pointed out its greatest service in grafting romantic love upon natural love, which until then had been supreme.

But it would be easy to ascribe too great a rôle, even here, to chivalry. The truth is not all told until chivalry is understood as an effect as well as a cause. Whatever may be said of the Middle Ages as tending to suppress the natural flow of intellectual activities, there can be no doubt that they were highly favorable to the development of emotional life. The intense religious fervor that burned in its cloisters for so many centuries served to create centers of feeling, and to increase the sensibility of all those nerve plexuses that constitute the true organs of emotion.

Whatever may be the physiological changes necessary to intensify the inner feelings, corresponding to the multiplication and diversification of the neurons of the brain by which the intellect is perfected, such changes went on, until the men and women of the eleventh century found themselves endowed with far higher moral organizations than those of the ancient Greeks and Romans. They had been all this time using their emotional faculties as they never had been used before, and the Lamarckian principle of increase through use is as true of those faculties as it is of external muscles and organs. It is true of the brain, too, and when educationalists wake up to this truth the only solid basis for scientific education will have been discovered. But without a preparation in this latent growth of the emotional faculties neither chivalry nor romantic love could have made its appearance.

The crusades, contemporary to a great extent with chivalry, and due also to the surplus emotion, taking here a religious course, became also a joint cause in the development not only of romantic love but also of many other lofty attributes, both ethical and intellectual. They failed to save the holy city, but they gained a far greater victory than that would have been in rationalizing, moralizing, and socializing Europe. Any one who thinks they were a failure has only to read Guizot’s masterly summing up of their influence.7

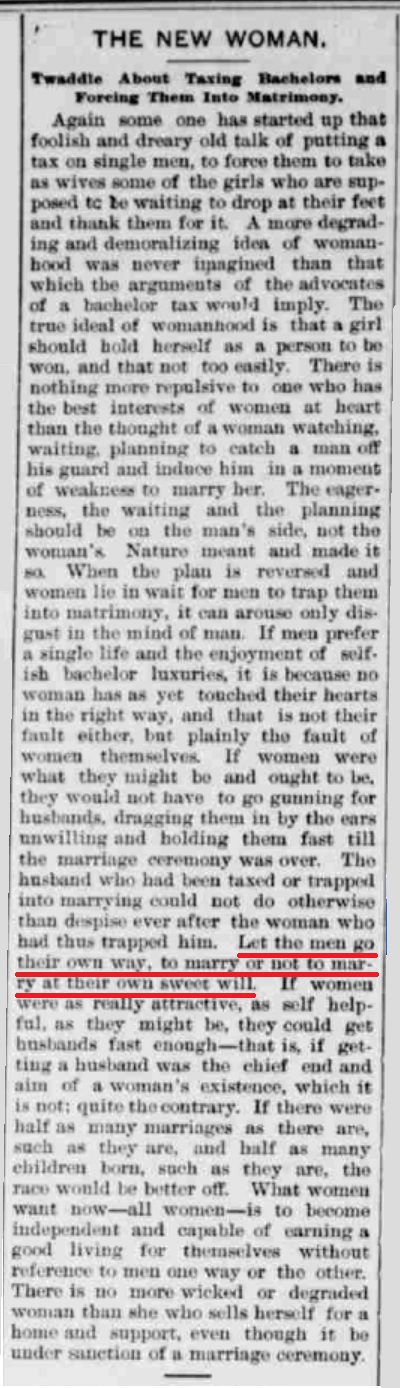

Romantic love was due primarily to the greater equality and independence of woman. She reacquired to some extent her long-lost power of selection, and began to apply to men certain tests of fitness. Romantic love therefore marks the first step toward the resumption by woman of her natural scepter which she yielded to the superior physical force of man at the beginning of the androcratic period. It involves a certain degree of female selection or gyneclexis, and no longer permitted man to seize but compelled him to sue.

But it went much farther than this. It did not complete a cycle and restore female selection as it exists in the animal world. It also did away with the pure male selection that prevailed throughout the androcratic régime. The great physiological superiority of the new régime cannot be too strongly emphasized. Its value to the race is incalculable. Female selection, or gyneclexis, as we saw, created a fantastic and extravagant male efflorescence. Male selection, or andreclexis, produced a female etiolation, diminutive stature, beauty without utility. Both these unnatural effects were due to lack of mutuality. Romantic love is mutual. The selection is done simultaneously by man and woman. It may be called ampheclexis. Its most striking characteristic consists in the phenomenon called “falling in love.”

It is not commonly supposed that this so-called “tender passion” is capable of cold scientific analysis. It is treated as something trivial, and any allusion to it creates a smile. Yet libraries are filled with books devoted exclusively to it, and these are as eagerly devoured by philosophers and sages as by schoolgirls. Such books, of course, are not scientific. They are fictions, romances, lyrics. Yet many of them are classic. Such always contain much truth, and this is almost the only way in which truth of this class is attainable. Serious writers fight shy of the subject. This emphasizes the idea that the subject is not serious. But as it is the most serious of all subjects this naturally creates an almost universal hypocrisy. My favorite way of illustrating this hypocrisy is by contrasting the attitude of society toward a couple, say on the day before and the day after their marriage.

To heighten the contrast let us suppose first that one of the two dies on the first of these days. The other is not even a mourner at the funeral. Next that one dies on the latter of these days. The other is then the chief mourner! Yet what real or natural difference is there between the relations of the two on the two days? Evidently none whatever. The only differences in their relations at the two dates are purely artificial and conventional.

Over and over again in the course of our studies into the origin and nature of life, mind, man, and society we have encountered the mysterious but silent power that unconsciously compasses ends not dreamed of by, the agents involved, the unheard voice of nature, the unseen hand, the natura naturans, the future in the act of being born. But nowhere has there been found a more typical or more instructive example of this than that which is furnished by romantic love. The end is nothing less than perfectionment of the human race. Whatever individuals may desire, the demand of nature is unmistakable. Primarily the object is to put an end to all tendencies toward extremes and one-sided development. It has been said that this mutual selection tends toward mediocrity.

This is not strictly true, but there can be no doubt that it tends toward the establishment of a mean. That mean may be regarded as an ideal. It is not an ideal in the sense of exceptional beauty, unusual size, excessive strength, or any other extraordinary quality. It is an ideal in the sense of a normal development of all qualities, a symmetrical rounding out of the whole physical organism. In this of course certain qualities that are considered most valuable fall considerably below the level attained in certain individuals, and this is why it has been supposed to aim at mediocrity. But it is certainly more important to have a symmetrical race than to have a one-sided, top heavy race, even though some of the overdeveloped qualities are qualities of a high order.

When a man and a woman fall in love it means that the man has qualities that are wanting in the woman which she covets and wishes to transmit to her offspring, and also that the woman has qualities not possessed by the man, but which he regards as better than his own and desires to hand on to posterity. By this is not meant that either the man or the woman is conscious of any of these things. They are both utterly unconscious of them. All they know is that they love each other. Of the reasons why they love each other they are profoundly ignorant.

It is almost proverbial that tall men choose short wives, and the union of tall women with short men is only a little less common. Thin men and plump girls fall in love, as do fat men and slender women. Blonds and brunettes rush irresistibly together. But besides these more visible qualities there are numberless invisible ones that the subtle agencies of love alone know how to detect. All such unconscious preferences, often appearing absurd or ridiculous to disinterested spectators, work in the direction of righting up the race and bringing about an ideal mean.8

The principle works in the same way on mental and moral qualities, which are at bottom only the expression of internal instead of external differences in the anatomy of the body. For a bright mind is the result of the number and development of the brain cells, and all the manifold differences in character are ultimately based on the different ways in which the brain, the nervous system, and the entire machinery of the body is organized and adjusted.

Generally speaking persons of opposite “temperaments,” whatever these may be, attract each other, and the effect is a gradual crossing and mutual neutralizing of temperaments. The less pronounced these so-called temperaments the better for the race. They are in the nature of extremes, idiosyncracies, peculiarities, often amounting to intolerable and anti-social caprices, and producing in their exaggerated forms paranoiacs, mattoids, and monomaniacs. Love alone can “find the way” to eliminate these and all other mental, moral, and physical defects.

Romantic love is therefore a great agent in perfecting and balancing up the human race. It follows as matter of simple logic that it should be given full sway as completely as comports with the safety and stability of society. All attempts to interfere with its natural operation tend to check the progress of perfecting the race. Under the androcratic régime, during which woman had no voice in the selecting process, and under the patriarchal system generally where the marrying is done by the patriarch and neither party is consulted, nature’s beneficent aims were thwarted, races grew this way and that, and mankind acquired all manner of physical and mental peculiarities. There were of course counteracting influences, and natural love, especially in the middle classes, helped to maintain an equilibrium, but male selection dwarfed woman and slavery dwarfed both sexes.

The races of men with all their marked differences have doubtless been in large part due to the want of mutuality in selection for purposes of propagation. This mutual selection under romantic love can be trusted not to work the extermination of the race from over-fastidiousness. It operates always under the higher law of reproduction at all events. This is proved by the universal influence of propinquity. “Great is Love, and Propinquity is her high priest.”

If there be but one man and one woman on any given circumscribed area they may be depended upon to love and to procreate. Very bashful persons who shun the opposite sex usually in the end marry the ones with whom circumstances forcibly bring them into more or less prolonged contact. The constant enforced separation of the sexes in the supposed interest of morality causes the sexual natures of those thus cut off from the other sex to become so hypertrophied that there is little chance for selection, and unions, too often illicit, take place with little concern for preferred or complementary qualities. Contrary to the views of moral theorists who advocate such enforced separation, marriages are fewer and occur later in life in societies where the sexes freely commingle and where there is the least restraint.

It is also in such societies that the closest discrimination takes place and that the finest types of men are produced. Where a reasonable degree of freedom of the sexes exists and there is no scarcity of men or of women, this passion of love becomes from a biological, from an anthropological, and from a sociological point of view, the highest of all sanctions. It is the voice of nature commanding in unmistakable tones, not only the continuance, but also the improvement and perfectionment of the race. In cases where arbitrary acts or social convention in violation of this command produce conjugal infelicity and despair, one might even indorse the following statement of Chamfort: –

When a man and a woman have a violent passion for each other, it always seems to me that, whatever may be the obstacles that separate them, husband, parents, etc., the two lovers belong to each other by Nature and by divine right in spite of human laws and conventions.

It is a curious fact that there is always a touch of the illicit in all the romances of great geniuses – Abelard and Héloïse, Dante and Beatrice, Petrarch and Laura, Tasso and Eleonora, Goethe and Charlotte von Stein, Wilhelm von Humboldt and Charlotte Diede, Comte and Clotilde de Vaux – and the romantic literature of the world has for one of its chief objects to emphasize the fact that love is a higher law that will and should prevail over the laws of men and the conventions of society. In this it is in harmony with the teachings of biology and with those of a sound sociology.

With regard to the essential difference between romantic love and natural love, it consists chiefly in the fact that the passion is satisfied by the presence instead of the possession of the one toward whom it goes out. It seems to consist of a continuous series of ever repeated nervous thrills which are connected if the object is near, but interrupted and arrested if the object is absent. These thrills, though exceedingly intense, do not have an organic function, but exist, as it were, for their own sake. That they are physical is obvious, and they are intensified by various physical acts, such as kissing, embracing, caressing, etc. In fact it is known that sexuality is not by any means confined to the organs of sex, but is diffused throughout the body. Not only are there nerves of sex in many regions, but there is actually erectile tissue at various points and notably in the lips.

Romantic love gives free rein to all these innocent excitements and finds its full satisfaction as romantic love in these. Anything beyond this is a return to natural love, but it is known that such a return is not absolutely necessary to complete and permanent happiness. This is the great superiority of romantic love, that it endures while at the same time remaining intense. It is probably this quality to which Comte alludes in the passage first introduced into his dedication of the “Positive Polity” to Clotilde de Vaux, and then put as an epigraph at the head of the first chapter: “One tires of thinking and even of acting, but one never tires of loving.”9

But “true love never runs smooth,” and herein lies the chief interest of romantic love for sociology and its main influence on human progress. Besides its effect thus far pointed out in perfecting the physical organization of man, it has an even greater effect in perfecting his social organization. The particular dynamic principle upon which it seizes is that which was described in Chapter XI under the name of conation. It was there shown that the efficiency of this principle is measured by the distance in both space and time that separates a desire from its satisfaction. It is the special quality of romantic love to increase this distance. Under sexual selection proper, or gyneclexis, male desire was indeed long separated from its satisfaction, and the interval was filled by intense activities which produced their normal effects according to the Lamarckian law.

But these effects, due to male rivalry, were purely biological and only showed themselves in modifications in organic structure. They produced secondary sexual characters and male efflorescence. This, as we have seen, must have lasted far into the human period. During the long period of androcracy that followed this stage, there was no selection, but only seizure, capture, rape, the subjection, enslavement, and barter of woman. There was no interval between the experience and the satisfaction of desire on the part of men, and very little effort was put forth to obtain women for this purpose.

Hence during the whole of this period neither the Lamarckian principle nor the principle of conation could produce any effect. For the great majority of mankind this condition prevailed over the whole world, with greater or less completeness, down to the date of the appearance of romantic love. It still prevails within certain restrictions and under various forms and degrees, in all but the historic races. Under male sexual selection, or andreclexis, so far as its influence extended, there was no interval between desire and satisfaction, no effort, no conation. Its effects were confined to physical modifications, primarily in woman, due to inheritance of the qualities selected by men. With the advent of romantic love, or ampheclexis, all this was changed.

So far as physical modification is concerned the effect was doubled by its application to both sexes alike, and instead of producing anomalies and monstrosities it worked, as already shown, for equilibration, symmetry, and normal average qualities or ideals. But here we also enter the field of social dynamics, and the principle of conation finds full expression.

Schopenhauer10 has acutely pointed out that the true romance never deals with happiness attained, but only with the prolonged struggle for happiness, with the troubles, disappointments, labors, and efforts of all kinds in search of happiness. It leads its heroes through a thousand difficulties and dangers, and the moment the end is reached the curtain falls! Tarde, well says11 that love is essentially a “rupture of equilibrium.” The entire course of a romantic love is a heroic struggle for the restoration of disturbed equilibrium. What does all this mean? It means intense activity on the part of great numbers of the human race at the age of greatest efficiency.

All this activity is expended upon the immediate environment and every throe of the struggle transforms the environment in some degree. The greater part of this transformation is useful and contributes to its full extent to social progress. In the early days and in the upper classes the demands of woman may have been somewhat trivial. Man must do something heroic, must prove his worthiness by acts of prowess, and such acts may even be opposed to true progress. But they at least develop manhood, courage, honor, and under the code of chivalry they must have a moral element, must defend the right, protect the weak, avenge dishonor, and uphold virtue.

But in the lower ranks even then, and everywhere since the fall of the feudal system, woman demanded support and the comforts of life, luxuries where possible, and more and more leisure and accomplishment. To-day she demands a home, social position, ease, and economic freedom. More and more, too, she requires of men that they possess industry, thrift, virtue, honesty, and intelligence.

Man must work for all this, and this struggle for excellence, as woman understands that quality, is an extraordinary stimulus, and leads to all forms of achievement. But man also selects. Romantic love is mutual. Woman has as much to lose as man if it results in failure. And man sets ideals before woman. She must be worthy of him and she gently and naturally bows to his will and follows the course that he gives her to understand is most grateful to him. Thus she develops herself in the direction of his ideals and both are elevated. She may also to some extent transform the environment, if it be no more than the inner circle of the family.

The combined effect, even in an individual case, is considerable, and when we remember that in any given community, town, city, state, or country, the majority of men and women pass at least once, sometimes twice or several times, through the phase of life known as being in love, waiting and working for the longed-for day when they are to possess each other, struggling to prepare themselves for each other and for that happy event, we can readily believe that such a stimulus must work great social results. The history of the world is full of great examples, but the volume of achievement thus wrought is made up of thousands, nay, millions of small increments in all lands and all shades and grades of life, building ever higher and broader the coral reef of civilization.

_______________________________

REFERENCES:

1) International Journal of Ethics, Vol. VI, July, 1896, p. 453.

2) “Antimachus of Colophon and the Position of Women in Greek Poetry,” by E. F. M. Benecke, London, 1896. “Primitive Love and Love Stories,” by Henry T. Finck, New York, 1899.

3) “Angola and the River Congo,” by Joachim John Monteiro. In two volumes. London, 1875, Vol. I, pp. 242-243.

4) “Travels in Southern Africa,” in the years 1803, 1804, 1805, and 1806, by Henry Lichtenstein, English translation, Dublin, 1812, p. 261.

5) Journals, etc., Vol. II, p. 321.

6) “Histoire de la Civilisation en France depuis la chute de I’Empire Romain,” par M. Guizot, 3e éd., Vol. III, Paris, 1840, Sixième Leçon, pp. 351-382.

7) “Histoire générale de Ia Civilisation en Europe depuis la chute de I’Empire Romain,” par M. Guizot, 4e éd., Paris, 1840, Huitième Leçon, pp. 231-257.

8) The reverse is of course also true, and a decided aversion between a man and a woman means that their union would result in some prominent detect or imperfection in the offspring. The extent to which the great number of misfits in society, of people who are out of harmony with the social environment, of which criminals only represent the comparatively rare extreme cases, are due to conventional and compulsory marriages, which ought never to have been contracted, and which ought to be annulled as soon as they are found to be wrong, is little reflected upon, and society and the church continue to denounce divorces, when the very desire for divorce proves that such marriages are violations of nature and foes of social order and race perfection.

9) “On se lasse de penser, et même d’agir; jamais on ne se lasse d’aimer,” “Politique Positive,” Vol. I, Dédicace, p. viii; Discours préliminaire, p. 1.

10) “Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung,” Vol. I, pp. 377-378.

11) “La Logique sociale,” par G. Tarde, Paris, 1895, p. 426.